Abstracts and How to Write Them

advertisement

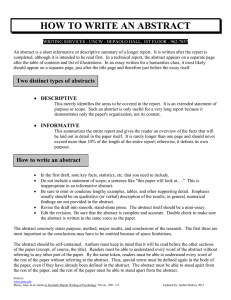

Abstracts and How to Write Them There are many forms and uses of an abstract, but in general an abstract is a short summary of completed research, whether contained within/derived from a single text or multiple texts. If done well, it makes the reader want to learn more about the research/article. Writing an effective abstract combines elements of the summary and synthesis skills we have developed this quarter. The particulars of an abstract will be determined by the discipline or field of study for which it is being written, and its specific purpose. Two of the most common uses for an abstract are selection and indexing. Abstracts allow readers who may be interested in a longer work to quickly decide whether it is worth their time to read it. Also, many online databases use abstracts to index larger works. They are often used as the cover sheet for submission of your work, for example when submitting articles to academic journals, applying for research grants, or writing a proposal for a book or conference presentation. However, there are basic components of an abstract in any discipline (though you will find many different names for these elements): purpose, methods, scope, results, and conclusions/recommendations. 1) Purpose/motivation/problem statement: Why do we care about the problem? What practical, scientific, theoretical or artistic gap is your research filling? What is the importance of the research? Why would a reader be interested in the larger work? 2) Methods/procedure/approach: What did you actually do to get your results? (e.g. analyzed 3 novels, completed a series of 5 oil paintings, interviewed 17 students) 3) Scope: What is the range of the material dealt with in the research? What does it cover, and what limits did you place on your research/investigation? An abstract for an essay on Shakespeare’s comedies, for example, would state that the Bard’s comedies make up the focus of the essay. 4) Results/findings/product: As a result of completing the above procedure, what did you learn/invent/create? How has your understanding of the topic changed or deepened your thinking? What kind of answers to your research question did you uncover? 5) Conclusion/recommendations/implications: What are the larger implications of your findings, especially for the problem/gap identified in step 1? How does this work add to the body of knowledge on the topic? What changes should be implemented as a result of the findings of the work? However, it's important to note that the weight accorded to the different components can vary by discipline. For models, try to find abstracts of research that is similar to your research. There are two primary types of abstract: descriptive/indicative and informative/informational. Descriptive/indicative abstracts A descriptive or indicative abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract describes the work being abstracted. Some people consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short—100 words or less. Informative/informational abstracts The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the writer presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the complete article/paper/book. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract (purpose, methods, scope) but also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is rarely more than 10% of the length of the entire work. In the case of a longer work, it may be much less. How to write an abstract As I mentioned, an abstract calls on your skills of summary and synthesis (analysis also plays a large part in any research project, but factors most in your assessment of sources). You must be able to synthesize the sources that you have found, identifying key connections or establishing how each contributes to the central idea you have been investigating, and then summarize your findings both in terms of identifying connections and discussing their collective significance. A good first step is to reexamine the work you have done so far (whether it is your entire project or a portion of it). Look specifically for your objectives, methods, scope, results, and conclusions/recommendations. After reexamining your work, write a rough draft without looking back at the materials you’re abstracting. This will help you make sure you are condensing the ideas into abstract form rather than simply cutting and pasting sentences that contain too much or too little information. We will start practicing the process with some brief invention writing. Take five minutes to jot down some notes about what the research project is about, interesting ideas you have discovered, problems you ran into in your research, and connections between texts that you have seen develop. Next, working from those notes, start to organize your thinking along the following lines: 1) State your motivation for the research project. Include why you decided to research the issue and why your audience should care about the topic. Include your research question. 2) Describe briefly your research methods, or how you obtained your results. Consider the type of search tools and terms you used, and any knowledgeable people you contacted or original research you conducted. 3) Consider the scope of your project. In what ways did you limit the focus of your research? Conversely, did you find your scope too narrow, and, if so, how did you broaden your outlook? 4) Summarize your findings. Include what you learned (or are learning) as a result of your research. 5) State your conclusion(s). If your findings have larger implications, include them in the conclusion. If your research left you with new questions or suggested specific recommendations, include those.