– Is the End in Sight? The Age of Hyper-Individualism

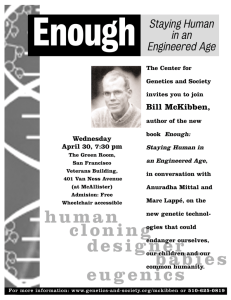

advertisement

The Age of Hyper-Individualism – Is the End in Sight? In “Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and The Durable Future” (Holt Paperbacks, 2007) author Bill McKibben describes the modern American personality as increasingly hyperindividualistic. This uniquely American state of mind is, perhaps, the natural evolution of our society– founded as it were by strong-willed people who left the confines of their small villages and pre-destined futures to find their place in the New World– independent thinkers, reformers, tamers of the wilderness — many of them newly armed with basic literacy and therefore direct access to new ideas— all of this with the engines of the industrial revolution already rumbling in the not too distant future. McKibben notes that while our liberation from great deprivation has brought us nearly unfathomable benefits (who among us would really choose to live as we did 300 years ago– cold half the time, hungry most of the time, dirty, sick, and deeply and grieving for the loss of one precious child after another…) the extent of this liberation has now exceeded our ability as humans to balance opportunity with responsibility. Our houses have doubled in size over the last 30 years and many of us have both witnessed and participated in creating the ”new normal” for affluent suburban lifestyles– 2 acre minimum lot size, 3000 sq. ft. minimum house size, 3 car garages and “trophy kitchens” that are larger than the total amount of shared common space that existed in most of our grandparents homes. We leave our homes daily and travel far for long days at work and we delegate both the care of our lawns and our children to strangers. Few of us know our neighbors any more– and we don’t have time to attend the annual town budget meetings. McKibben writes “what ties are there left to cut? We change religions, spouses, towns, professions with ease. Our affluence isolates us ever more. We are not just individualists: we are hyper-individualists such as the world has never known” (page 96). The more money we have the less we give of ourselves to our community – and it shows. Outside of our carefully framed suburban view the overall quality of American schools has declined to the extent that we significantly lag other developed nations, our overall health status ranks below most other developed nations, and we have the world’s highest proportion of our population in prison. Now that we have it all are we any happier? Not according to a growing body of research. McKibben references several studies– one conducted annually by the National Opinion Research Council since WWII which asks people whether whether they are–overall– very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy. Our “very happy” period reached its peak in the 1950′s and has declined ever since (McGibben, page 45). We know, from numerous studies, that once our basic needs are met– money doesn’t buy happiness. ” In fact, past the point of basic needs being met, the “satisfaction “data scramble in mind-bending ways. A sampling of Forbes magazine’s “richest Americans” has happiness scores identical with those of the Pennsylvania Amish and only a whisker above those of the Swedes, not to mention Masai tribesmen. The “life satisfaction” of pavement dwellers- that is homeless people — in Calcutta was among the lowest recorded, but it almost doubled when they moved into a slum, at which point they were basically as saisfied with their lives as a sample of college students drawn from forty-seven nations. (McKibben, page 42.) So where has this all left us? Mr. McKibben’s book was published in 2007 – before the horrific financial market meltdown that started in early 2008 and is still in process– like a slow motion crash scene. Our houses have declined in value by an average of 20%, our retirement savings by 30%, and our jobless numbers have doubled over that time. And now, more than ever before, the true threat of climate change is becoming very clear. The excesses of the “new gilded age” have become excruciatingly visible to all but those who were most invested in its continuance. It is hard these days to even remember the sense of self-satisfaction that came with knowing your house was making you rich while you slept. And those feelings of affluence led us to make many daily decision about how we spent our time and our money that, in retrospect, lacked the mature perspective a falling net worth provides. Now frugal is “in” and excessive consumption is “out.” We have a new president and a new state of mind. We are planting gardens and recycling again. Enrollment in volunteer programs is up. One of our local high schools had a “prom dress exchange” — apparently someone finally figured out that it was wasteful to spend hundreds on dress that will only be worn once. And well-attended Green Living events have begun to appear throughout New England which have as their focus sustainable living, re-localization, alternative energy and re-purposing our lives. These are good signs that America may finally be waking up to the realization that our best hope for the future is in firm realization that both our human and our natural resources are gifts to be preserved for the benefit of our society, not commodities to be extracted and spent. 907a5f5679 /2009/06/14/the-a guest