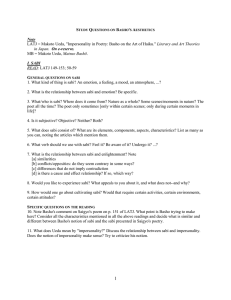

S Q B '

advertisement

STUDY QUESTIONS ON BASHO'S POETICS Texts Makoto Ueda, "Impersonality in Poetry: Basho on the Art of Haiku." Literary and Art Theories in Japan. On e-reserve. Makoto Ueda, Matsuo Bashō. David Barnhill, Bashō’s Journey. I. SABI READ: “Impersonality in Poetry,” 149-153 and Matsuo Bashō, 50-59. GENERAL QUESTIONS ON SABI 1. What kind of thing is sabi? An emotion, a feeling, a mood, an atmosphere, ...? 2. What is the relationship between sabi and emotion? Be specific. 3. Is sabi a characteristic of a particular moment-scene or an ongoing fundamental quality of reality? Does the poet of sabi experience sabi only sometimes in special moments (e.g. autumn evening) or is sabi a continuous aspect of her or his experience of the world? 4. Is sabi subjective? Objective? Neither? Both? 5. What does sabi consist of? What are its elements, components, aspects, characteristics? List as many as you can, noting the articles which mention them. 6. What verb should we use with sabi? Feel it? Be aware of it? Undergo it? ...? 7. What is the relationship between sabi and enlightenment? Note [a] similarities [b] conflicts/opposites: do they seem contrary in some ways? [c] differences that do not imply contradiction [d] is there a cause and effect relationship? If so, which way? 8. Would you like to experience sabi? What appeals to you about it, and what does not--and why? 9. How would one go about cultivating sabi? Would that require certain activities, certain environments, certain attitudes? SPECIFIC QUESTIONS ON THE READING 10. Note Basho's comment on Saigyo's poem on p. 151 of “Impersonality in Poetry”. What point is Basho trying to make here? Consider all the characteristics mentioned in all the above readings and decide what is similar and different between Basho's notion of sabi and the sabi presented in Saigyo's poetry. 11. What does Ueda mean by "impersonality?" Discuss the relationship between sabi and impersonality. Does the notion of impersonality make sense? Try to criticize his notion. 1 II. THE POETIC SPIRIT: THE SOURCE OF CREATIVITY; SELF & UNIVERSE READ: “Impersonality in Poetry,” 147-148, Matsuo Basho 132, Bashō’s Journey 29 The key passage is found in Bashō’s third travel journal. Barnhill translates the title of the journal as Knapsack Notebook, while Ueda translates it Record of a Travel-Worn Satchel. That key passage is the second paragraph of Knapsack Notebook. See p. 29 of Barnhill’s Bashō’s Journey, starting “Saigyō’s waka…”. One translation of that paragraph by Ueda is found in LATJ 147-148 (starting “There is a common element. . .”). Another translation by Ueda is found in Matsuo Bashō, p. 132 (starting “One thing permeates. . .”). Compare all three translations. The key term is called “poetic spirit” in Ueda’s LATJ, “spirit of the artist” in his Matsuo Bashō, and “aesthetic spirit” in Barnhill’s Bashō’s Journey. 1. Describe the "poetic spirit". Examine that notion critically. What is it? Where is it? How is it related to the self? What does it do? How does it work? What would keep it from working? What would we need to do to make it work? What does Basho value it so much? Does the idea appeal to you--would you like to have it working in you? Why or why not? If it does appeal to you, are you inclined to work toward it? Why or why not? 2. What is the relation between the poetic spirit and nature? What does he mean by "follow the ways of the universe and return to nature? Compare the three different translations (two by Ueda and one by Barnhill). How do they differ? Do those differences suggest different ideas or attitudes? Which translation seems to you the best? Why? 3. What does he mean by saying "everything he sees becomes a flower, and everything he imagines turns into a moon"? Do you agree with him--is there a flower in a dead tree...in dog shit? What assumptions would lead to his idea? What would it be like to experience life that way? What keeps you from seeing a flower and a moon everywhere? How would you go about creating that vision? Would you want that vision? 4. Describe the affinities and differences between Basho's notion of poetic spirit and Buddhism's notion of the self, Buddha nature, and spontaneity. 5. According to Ueda, what are the two aspects of the poetic spirit and what is their ideal relationship? What is meant by this idea? [LATJ 148-9] III. HOW A POEM IS CREATED: "INSPIRATION” READ: “Impersonality in Poetry” 156-9; Matsuo Basho 167-8, “Western Writers on Direct Perception” and “Western Writers on Spontaneity in Writing” (Study Aids). Note: The issue here is how a haiku poet creates a poem: what is experienced, and how the poem is born. There are two parts to this: [1] the initial experience or moment of consciousness in relation to the poet’s subject (e.g. a pine tree), and [2] the act of creation in writing the poem. In LATJ (157-8) Ueda calls the first aspect [#1 above] "instantaneous perception," and in MB (166) he uses the term "impression." In LATJ (159) Ueda calls the second aspect “instantaneous writing.” INSTANTANEOUS PERCEPTION (IMPRESSION): 1. What occurs in "instantaneous perception?" What is the experience like? What is the relation between the poet and reality during a moment of this kind of perception? Have you ever had such an experience? 2. This type of experience is related to Basho's notion of "slenderness." What does slenderness mean? What does this process consist of? Can this experience last or is it momentary? 2 3. This experience is also related to Basho's admonition: "learn about a pine tree from a pine tree...?" [157-8] How does Doho, Basho's disciple, explain his master's comment? What happens to the notion of the self here? 4. Critically assess the notion of feelings here. Does the poet bring feelings to the object? Does a thing really have feelings? Does the phrase "feelings spontaneously emerge out of the object" make sense? 5. Read the selection of “Western Writers on Direct Perception” in the Study Aids. How does this description of Bashō’s consciousness compare to what these Western writers have said about the aesthetic consciousness? 6. Does the experience make any sense to you? Have you ever had moments like this? What do you think keeps you from having such experiences? Would you want to have them? 7. What are the similarities AND the differences between this experience and Buddhist enlightenment. COMPOSITION: After the initial experience of perception or impression comes the creative act of composition. Basho says that the act of composition is one in which the poem "grows" rather than being “made”. 8. Basho makes a distinction between two types of composition: growing [or becoming] and making. What is the difference? Why is "growing" better than "making?" What is required to achieve a grown poem? What is left out of a made poem? Note Ueda's metaphor in “Impersonality in Poetry” [p. 158] of the object color the transparent mind of the poet. Is that an effective analogy? Does that idea make any sense to you? Do you agree with Basho that a grown poem is better, and is the only "real" poem? 9. Another aspect of Basho's view of composition is his notion of instantaneous writing [“Impersonality in Poetry,” 159]. "Let there not be a hair's breadth separating your mind from what you write." What does he mean? Why does he say that? Keep in mind that Basho was known to rework his poems through several drafts. Does this fact refute his statements about instantaneous composition? 10. Read the selections from “Western Writers on Spontaneity in Writing” in the Study Aids. In what way is her writing spontaneous, and what happens when she is not being spontaneous? Can rewriting be spontaneous? What are Butala’s points about writing? How do these statements relate to Basho's point about composition? 11. Describe in as much detail and subtlety as possible the affinities between Basho's notion of composition and Buddhism's ideals. IV. SHIORI, KIREJI, YOJO, REVERBERATION, FRAGRANCE, REFLECTION READ: “Impersonality in Poetry” 154-155 & 160-163; Matsuo Bashō 161-164. 1. What is shiori? How is its meaning reflected in the Japanese words for flexibility and withering? [“Impersonality in Poetry” 154] Why does Bashō value this quality? 2. What is yojō, and why does Bashō value it? What are the ways of achieving yojō? Does it seem to be the same as the suggestiveness valued by Teika in court poetry? [Matsuo Bashō 161-3] 3. Summarize reverberance, fragrance, and reflection. What is their most basic and common meaning? What are the differences between them? [Matsuo Basho 163-4; “Impersonality in Poetry” 160-3] 3 V. HOW A POEM MEANS and THE PROBLEM OF INTERPRETATION 1. What is meant by the phrase "the mind goes and returns?" Why is it valued? Can you feel your mind go and return in any of his poems? Which ones? 2. What is the "meaning" of a haiku poem? 3. What should the reader do with a haiku poem? "Experience" it? "Interpret it?" "Understand it?" Or what? What is required of the reader? 4. What is involved in "interpreting" a haiku poem? What constitutes a valid and an invalid interpretation? 5. What kind of ambiguity is involved in a haiku poem? Are there several meanings? VI. LIGHTNESS: BASHO'S INCORPORATION OF THE ORDINARY READ: “Impersonality in Poetry” 164-170; Matsuo Bashō 62-66, 158-161. 1. Describe lightness. 2. How does lightness relate to sabi? Is it a replacement? A complement? An extension? 3. Why did Basho begin to value and emphasize lightness? 4