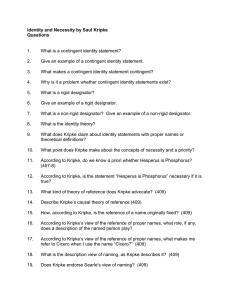

Mentality and Modality John P. Burgess Department of Philosophy

advertisement