Students’ Classroom Experiences as Guides for Better Teaching Keynote Address

advertisement

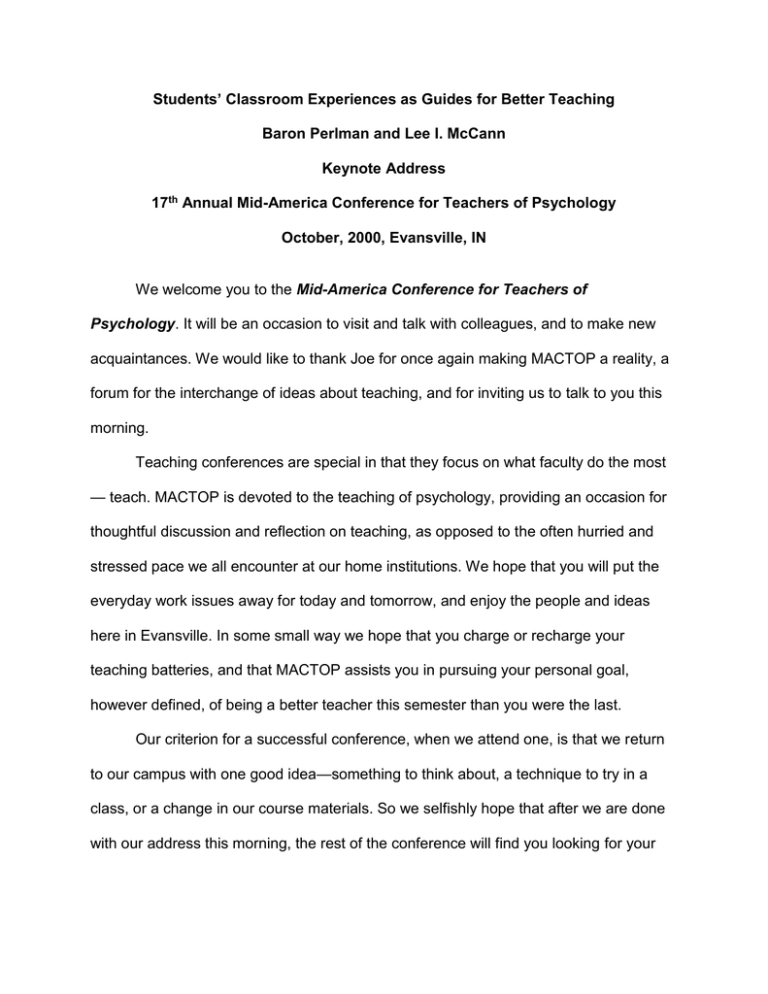

Students’ Classroom Experiences as Guides for Better Teaching Baron Perlman and Lee I. McCann Keynote Address 17th Annual Mid-America Conference for Teachers of Psychology October, 2000, Evansville, IN We welcome you to the Mid-America Conference for Teachers of Psychology. It will be an occasion to visit and talk with colleagues, and to make new acquaintances. We would like to thank Joe for once again making MACTOP a reality, a forum for the interchange of ideas about teaching, and for inviting us to talk to you this morning. Teaching conferences are special in that they focus on what faculty do the most — teach. MACTOP is devoted to the teaching of psychology, providing an occasion for thoughtful discussion and reflection on teaching, as opposed to the often hurried and stressed pace we all encounter at our home institutions. We hope that you will put the everyday work issues away for today and tomorrow, and enjoy the people and ideas here in Evansville. In some small way we hope that you charge or recharge your teaching batteries, and that MACTOP assists you in pursuing your personal goal, however defined, of being a better teacher this semester than you were the last. Our criterion for a successful conference, when we attend one, is that we return to our campus with one good idea—something to think about, a technique to try in a class, or a change in our course materials. So we selfishly hope that after we are done with our address this morning, the rest of the conference will find you looking for your 2 second or third good idea, and by the way, Joe does not charge extra for those. Please let us know if you did get that idea—we have no way of finding out unless you tell us. What we will emphasize this morning is how your students can be a source of ideas and data for your reflection on, and improvement of, your teaching. We will begin by: Talking about the four ways that faculty members learn and typically get feedback about their teaching. The fourth differs from the first three in that it involves feedback from students. Our main point this morning is that the perceptions and ideas we have about our teaching, our reflections on it, and the changes we make in how we teach, are all incomplete without student input. If we aspire to what Stephen Brookfield calls “becoming a reflective teacher” we need our students’ input. Thus we emphasize the idea of “listening to students’ voices” and will provide some widely used, specific ways of obtaining student feedback about our teaching. Next we turn to student pet peeves, a specific technique for using students’ experiences as learners to gain a more complete picture of our teaching, beginning with how this method or any of those already mentioned are valuable sources of powerful information about our teaching. We have gathered some data about student pet peeves, and asking students this question is a nonthreatening way of getting feedback from them and a nonthreatening way to assist us in making 3 changes in our teaching. But we want to do more than merely share with you what students dislike about teaching. We will have a question or two for you to answer, and then, We will turn to the pet peeve data and see what you think of it. Finally we want to talk about specific ways colleagues have changed their teaching in response to pet peeve information and to share with you a few “lessons learned” about pet peeves. Learning About Our Teaching There are four ways to learn about your teaching. 1. Autobiographical The first way to learn about one’s own teaching is autobiographical. You can put your feet up and think about successes and failures, and discuss them with others to clarify or deepen your thinking. Autobiographical learning about teaching can be done more systematically through writing of a teaching portfolio or a course portfolio (which contain other elements of learning as well). 2. Colleagues Colleagues are perhaps the most common way to learn about teaching. Peer review, if done well, is a good way to learn about one’s teaching by working with a colleague, and we will be presenting a workshop on Peer Review of Teaching later at MACTOP. We talk with colleagues, ask them questions and for opinions, ideas, truths, validation, support, and a friendly, listening ear. It is interesting how uncertain we often are about our own teaching, yet we often accept colleague’s viewpoints and ideas. How is it that we attribute to them so much knowledge and certainty when we ourselves are 4 so unsure? Just to let you in on a secret, many of them are much more unsure about their teaching than they ever let on. Many department and institutional cultures do not support disclosing uncertainty when it comes to teaching—they make it too risky. Senior faculty might appear not to know what they are doing, and who wants to be senior faculty (like us) who have spent a lifetime and still do not know how to teach perfectly. Junior faculty are afraid they will appear to be poor teachers if they admit they are not able and proficient masters of their courses and classrooms. But the truth is, or at least our guess is that the truth is, paradoxical in at least two ways. First, it seems likely, and we have data to suggest, that senior faculty and their junior colleagues are much more alike than different. Both struggle with their teaching, if they are honest about it, and struggle perhaps with many of the same elements of teaching. Teaching seems to be a task that no one ever masters. Current contextual developmental theory calls into question the popular stage theory idea that suggests that as we develop in any area of our life we move towards proficiency and wisdom, ending up having perfected some phase of life. Applying this idea to teaching, it seems unlikely that senior faculty are Teaching Gurus, or the Yodas of Pedagogy, if you will. One value of teaching conferences such as MACTOP, is that they provide a forum for us to talk about our teaching uncertainties, and to obtain support for our anxieties, questions, worries, and inquiries. If you have never attended a teaching conference we predict you will find it refreshing to be able to say, or hear someone else say, “I don’t know,” in regard to teaching. 5 The second paradox about being and becoming a good teacher is that the loss of innocence or naiveté about certainty is the beginning step in our growth as teaching faculty. Stephen Brookfield in his 1995 book, Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher calls this the RoadRunner phenomenon. In the classic RoadRunner cartoons the RoadRunner is chased by Wile E. Coyote, who never catches his nemesis. Typically the Coyote, despite his best entrepreneurial and creative efforts, and the best efforts of the Product Research Division of the ACME Company, ends up running, walking, or shooting himself out of a cannon and over a cliff. And he hangs there in mid air but does not fall. No, he does not fall…….. Until he realizes he is in mid-air—then he plummets to earth. That moment of knowing one is in mid-air, is the moment you have begun your growth as a teacher. The moment you begin to realize that what you assumed to be true about your teaching and students may not be true, that there are alternate ways, that you are unsure about how students perceive your best efforts, that your best efforts may need to be changed, that you can experiment with your teaching….. these and a host of other moments mark your end of innocence and your beginning development as a good teacher. It is a paradox. 3. The Literature Third, you can gather ideas helpful in understanding and improving your teaching from the literature. We are talking about more than the theoretical literature about students’ learning styles. There is a wide variety of literature on teaching and higher education. This literature points out, for example, that the pressures from your local campus coupled with national trends, weigh heavily on your teaching. Whether it be distance education, other uses of technology in teaching, pressures on tenure and the 6 hiring of more non-tenure line colleagues, diminished budgets and supports for teaching, or other elements, you do teach in a context both local and national. Reading helps us understand these contexts, and perhaps assists in controlling your blood pressure, or it may cause some blood pressure spikes. Other literature exists. Some authors have presented their own teaching experiences (autobiographical), others give you lots of simple ideas which are easily implemented and can greatly improve your teaching. Wilbert J. McKeachie’s book, Teaching Tips now in its 10th edition is one such example. The book based on our own Teaching Tips column which appears regularly in the APS Observer: Lessons Learned: Practical Advice for the Teaching of Psychology, is another such example. The teaching journal in our discipline, Teaching of Psychology, is an excellent source of data and ideas on teaching. Then there are books such as the one authored by Stephen Brookfield we have already mentioned on reflective teaching, which move one step beyond day-to-day teaching and force us to confront ourselves and our teaching at a more basic, more important level. 4. Students Students are the fourth way, and an extremely important way, to gain feedback about all aspects of our classes and courses. A truth -- There are few absolutes in the world of teaching. Let us offer one now, as part of our theme this morning. All of your disciplinary knowledge and efforts are incomplete if you focus on merely your side of the teaching equation, and do not ask the critical question: What does what I do mean for the experience and learning of my students? Asking this question of yourself automatically leads to greater depth in your 7 thinking about your teaching and increases the odds that you will teach in ways that are successful, however you define success. A second truth – also related to our theme. Your ideas and conclusions about how you are perceived by students, their interpretations of your teaching methods and your interactions with them, and how they feel about your courses and classes, are probably inaccurate, or at best incomplete. You need to ask students. So, we need to see ourselves through students’ eyes, never assuming that what we are doing is either understood by students or appreciated by them. Yet getting inside students’ heads is one of the trickiest pedagogic tasks facing us. At the same time it is absolutely crucial that we do so. When we can see ourselves as our students do, we understand the teaching-learning process from both our side and the students’ side—a more complete view of the classroom or course experience, To summarize, there are four sources of information one can consider in reflecting on one’s teaching. The first three—autobiographical (our own experiences), colleagues, and the literature, if taken by themselves, misdefine the gestalt that is teaching by omitting an important element – students. We argue that data from students provides a missing ingredient that is essential to our teaching efforts. Most faculty probably feel they already regularly solicit information from students by obtaining standardized student evaluation or opinions from them, typically at the end of a course. We talk with students, kibitz with them, and probably feel there are ample opportunities for them to speak up. Course end evaluations gather data after the course is over. Why 8 not consider student concerns by asking about them at the very beginning and during the course? Student opinion data often measure student satisfaction, giving us little if any useful information about the dynamics and rhythms of the course, and their experiences in it. We are left with data about whether they liked us, perhaps whether we challenged them, and how easy or hard we graded. And we are left to wonder, if we have been rigorous and challenged students, whether their course end anxieties have been projected back on us. Yet we need to invite students into the learning process, to connect our goals and their expectations and concerns. Knowing something about how students are learning and reacting to what we do, may, at the least, give us some insights into lack of motivation, poor preparedness, and disinterest on their part. With some insights into how students experience learning, and our courses and classes, we may be able to lessen the ways that we intimidate or confuse them. The literature can be helpful in providing mechanisms for getting inside students’ heads. We recommend Thomas A. Angelo and K. Patricia Cross’ 1993 book, Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers, 2nd Edition by Jossey-Bass. This book is an extensive collection of ways of allowing students to speak in their own voices. It estimates the amount of time and energy required for the faculty member to prepare, the students to respond, and for faculty to analyze the data collected for 50 classroom assessment techniques. Let us offer a few examples of how to obtain student feedback. Borrow what is useful. 9 The Minute Paper may be the most widely used assessment technique in the classroom. You simply decide what you want to focus on and learn about, and ask students to respond to any question you have of them. Typically the questions are variations of “What was the most important thing you learned during this class?” and “What important question remains unanswered?” Students write and return their responses. Student Learning Journals can have a variety of forms and purposes. But whether you count them toward a final grade or not, reading them yields insights into the students’ experiences in your courses. Troubleshooting is a technique where you save a few minutes each class or week to allow discussion of process, not content. This is a time for students to clarify, question, and raise concerns. The Critical Incident Questionnaire is handed out to students at the end of the last class you have with them each week. It does not focus on what they did or did not like, but instead on specific things that happened that were significant to them. Students turn in their feedback anonymously. Some teachers ask students to keep a copy for themselves (self-carbon form) and share results with the students at the beginning of the next week. You can or cannot follow this procedure. Students are typically asked five questions, all of which take 5 minutes or less to answer. 1. What did you find most interesting this week? 2. What did you find least interesting this week? 3. What action that anyone (teacher or student) took in class this week did you find most helpful? 10 4. What action that anyone (teacher or student) took in class this week did you find most puzzling or confusing? 5. What about the class this week surprised you the most? The critical incident questionnaire gives insights into teachable moments and when they occur, and informs faculty of what students perceive as the most critical moment (positively or negatively) of each week. Students’ feedback helps us understand classroom dynamics and how students are experiencing their learning and our teaching. It is a powerful way of seeing our teaching through students’ eyes. Letters to Successors occur at the end of the semester and thus have some of the same problems and criticisms as end-of-course numerical student opinion surveys. But they provide extremely powerful and useful feedback. Students are asked to write advice for your next semester’s class about the essential things a student needs to know and do to survive in your classroom and course. Whether you have students meet in small groups to discuss and identify major themes or turn them in individually, is your decision. Typically, students are asked to write: “What I know now that I wish I had known when the courses began?”, or "The most common and avoidable mistakes that I and others made in this class.” This information is then summarized and reviewed the first day of the next time you teach the course. You can even prepare a written handout for students, who often listen more closely to their peers than to us. All of these techniques seek student ideas and critiques of your teaching. The decision to ask for such information requires the courage to seek and consider student input, which may diverge from what we think we are doing as teachers, and how well we 11 are doing it. But remember: Good teachers think about and obtain information about their teaching. They strive to improve. They know and expect that students will not necessarily give them standing ovations for their teaching. It takes maturity as a teacher to realize the truth of this notion. As you learn about your teaching, you may be able to make some immediate changes, and you gain insights and information useful for your students. When we gathered data from students about the first day of class we were surprised to learn that many wanted to know more about their instructors. We now spend a few minutes during the first day of class telling students about who we are, and how we came to be teaching this specific class, and why we teach it the way we do. As Donna K. Duffy and Janet Wright Jones point out in their 1995 book, Teaching Within the Rhythms of the Semester, published by Jossey-Bass, you could enrich your syllabus with this information. We all might want to consider a section in our syllabus titled something like: My Beliefs About Teaching and Learning, Why I Teaching this Course the Way I Do, or What You Should Know About Me. How Getting Inside Students’ Heads is Important: Student Pet Peeves as an Example As we have been saying, students do scrutinize us closely and getting inside their heads is important. Now we will begin our specific example of asking students to provide their pet peeves of faculty teaching. Keep in mind that the value of soliciting peeves applies to many other mechanisms for getting student input. What makes 12 listening to students via their pet peeves, or any other way, about our teaching so valuable? The answer has many parts. 1. It invites students into the course. Asking students to spend a few minutes telling us what they like and dislike about faculty teaching suggests to students that this course may, in some way, be different. The instructions for the pet peeves exercise may contain information students have never heard. These instructions say: I am interested in improving my teaching. To that end I want to learn your pet peeves (major likes/dislikes/annoyances, things which are unfair) about faculty whose courses you have taken (both in and out of psychology). Take a few minutes and write down your two or three major pet peeves about faculty when they teach. What bothers you or annoys you the most? All responses will be anonymous and confidential. 2. It makes students feel valuable. An instructor typically asks for students’ pet peeves about faculty teaching during the first or second class period. It is an unusual request so early in the semester and very different from an end-of-course evaluation. By making this request teachers are communicating to students that they, the students, have thought about and formed useful opinions about their experiences as learners. 3. Such a request builds trust between students and teachers. Most students view the semester end evaluation of teaching as artificial and are surprised that anyone takes it seriously. After all, even if instructors read them, and make changes in how they teach, only the next course can be better and different, not the one they just completed. With a request for pet peeves the instructor is letting students know that 13 their feedback may help improve the very course in which they are enrolled. The teacher is seeking students' experiences as learners that previously have been private and personal. Following up use of pet peeves with other requests for student feedback builds a sense that open and honest communication is desirable and that students are valued. This solicitation for student pet peeves, at the beginning of the course, and about other classes, may help students overcome their understandable reluctance to voice misgivings to a faculty member. 4. The exercise takes little time and has minimal cost. The threshold for obtaining student feedback about teaching is extremely low. All one needs are some blank index cards and 5 minutes of time. 5. Instructors can make almost immediate changes in their teaching. As we hope to prove to you, it is really impossible to gain students’ opinions and not have something in one’s own teaching to work on. The changes made do not have to be major, and small changes may build confidence for larger changes in our teaching later. 6. It invites teachers to look at and change their own teaching with minimal resistance and anxiety. After all, students are not talking about our teaching, we haven’t taught the course yet. They are talking about other faculty members’ teaching. And we can select the easiest tasks to work on first, something as simple as arriving at class earlier. The student data will not be used negatively for renewal, tenure, or promotion decisions, and the effort to improve one’s teaching will be viewed positively by most colleagues, although curmudgeons will see it as a threat. 14 7. The potential for discovering “disconnects” is increased. The consequence of systematically listening to your students is that you increase the possibilities that you will experience the RoadRunner phenomenon. You may realize the disconnect between how well you think you teach and what students actually experience in your course. You begin to realize that what you thought was well thought out and clear is actually opaque. 8. We are alerted to problems before a disaster develops. For faculty not used to seeking student feedback and insight, the data may show that one or two of their teaching mechanics or tools are well known to students – and negatively so. Poor lecture mechanisms, lack of clarity on what is expected of students, and a poorly designed first day of class are all common examples. It is helpful to have this information and make use of it before students begin to miss class, another set of disappointing student evaluations, or a poor peer review by a colleague tied to promotion or tenure. Student feedback allows faculty to make improvements in their teaching. What was problematic, unfair, ambiguous, confusing, annoying, or at worst, unethical, can be worked on from the very beginning of the course. And true disasters may be avoided. Faculty may be sensitized to a style with humor that is offensive, to a teaching practice that borders on the unethical, or to a behavioral mannerism (e.g. looking at the floor when talking with students) that is demeaning. 9. Clarity of Purpose. If you begin to see yourself through your students’ eyes, you will find one immediate change in your teaching. You will begin to explain to them what you are doing and why, much more often. It will be automatic for you to do this. 15 It is possible that we can never be too clear or redundant in explaining and defining our goals and actions. And by doing so, you will explain your thinking to them and make them more knowledgeable about the course or class they are taking with you. We think an important outcome of this explaining is better rapport with students, and that it is possible they will be more willing to follow you where you take them during the course or class hour, because they will better understand your goals and motives as a teacher. 10. It can be fun. I decided to both speak more slowly when lecturing, to be very clear about when I was off on a tangent, and to curtail my use of tangents. I enlisted the class’s assistance throughout the semester. Students were urged to speak out, without raising their hands, and let me know when I either was speaking too rapidly, to point out to me I was on another tangent, or that given class time left, could I focus on material more relevant to the syllabus, text, upcoming exam, and so forth. Most students had never been allowed to do this before and took great glee in correcting me, and I, by the way, was grateful for the continuous feedback. Both students and I smiled when I had a “good” class and students often urged me to do better the next time. Rapport was excellent. Exercise for Audience Would you all please find something to write on. Since we are preaching to the choir, we assume you all are more reflective about your teaching than most. First, write down what you think is the one thing students most dislike about our teaching in general. 16 Then can you write down a few things about your teaching that you are reasonably confident would appear on a list of students’ pet peeves about other faculty members’ teaching. We’ll give you a minute or two to think about this. What did you come up with? Do we have some brave souls willing to self disclose? After all you already know that Barry was concerned about speed of lecturing and tangents. Conversation and Discussion. Thank you! Before we learn how good you are at predicting students concerns, let us ask one more question. This one may be slightly more difficult to answer, but you are among friends. Now that you have identified aspects of your teaching that are not exemplary and that you feel students have noticed, Why have you not addressed this problem already? Or Why have you not been successful in addressing this problem in your teaching? Conversation and Discussion. Thank you! All of us have teaching issues we have not addressed or not successfully addressed. This is what makes teaching so difficult, and a life long struggle. Had you successfully addressed 10 problems in your teaching in the last year or two, we expect you would have an 11th issue you wanted to work on. That is also what makes teaching so gratifying—sometimes it all comes together and it “works.” 17 Pet Peeves: The Data PASS OUT MANUSCRIPTS (OVERHEAD DISPLAYED) A few comments about the students’ pet peeves are in order: 65% of the peeves fell in one of the “teaching” categories, most emphasizing poor organization and planning, teaching mechanics, lecturing, testing procedures and exams, or a monotone voice. Some students complained exams cover only the text and others only the lecture, Some complained about use or nonuse of grading curves or requiring or not requiring attendance. You cannot please everyone! But if you can offer rationales and reasons to students for what you do, they have a better chance of understanding the “whys and how comes”, and accepting your approach. Respect elicited 10% of the peeves and the “general” category 18%. Lack of respect for students and poor use of class time elicited the most concerns. Positively, few faculty members seemed to demonstrate a lack of interest, competence, or depth in their subject or teaching, and most seemed to grade fairly. Students rarely complained about too much work, sexism, or racism. Of the many peeves (95, 7%) in the negative mannerism category a few were humorous (e.g., bad haircuts and wardrobes, sloppy dresser). 18 Question for participants: How good were you at predicting students’ pet peeves with our teaching? How many of you listed something about your own teaching that was on the list? Is there anything you found surprising? Having seen this list, is there anything you might do differently in your first class next week? Changing Our Teaching We are convinced of the power of pet peeves in improving teaching because of the behavior of our own colleagues in our department at UW Oshkosh. We had enlisted their assistance in gathering these data. Most of our colleagues have only an average interest in teaching enhancement work and few have ever attended a teaching conference. Nonetheless, of the 13 participating colleagues 11 made teaching changes during the first week of classes and all had maintained these changes 2 semesters later—and we twisted no arms. One enhanced lecture with more overheads. (Lee) One developed greater sensitivity to scheduling reading and assignments. One took extra care reviewing previous classes. One reduced pauses, “uh”, in lectures. One gave a brief break in a 90 minute class. One was clearer in grading criteria. One spoke more slowly (Barry). One arrived at class earlier. 19 Lessons Learned We learned several valuable lessons from asking students to share their experiences as learners and list their pet peeves about teaching. 1. The concerns listed in the table provide a starting point for improving instruction for any teacher. 2. Students know good teaching and are sensitive to not receiving it. 3. This is a simple, yet powerful, technique faculty can use to improve pedagogy. If faculty wish, they can easily remedy many of the teaching concerns identified. 4. Separating evaluation of teaching for personnel reasons, from improving one’s pedagogy because one chooses to, encourages faculty to become better teachers by responding to student concerns. Our colleagues at all ranks embraced improving their teaching willingly and energetically. Conclusion By being here you have demonstrated that you know that time and energy spent on teaching is an obligation you have to yourself, your students, your colleagues and institution. You have already reached the conclusion that talking about teaching is important. It is one sign that a faculty member respects and is committed to quality teaching. Even so simple a procedure as asking students about their pet peeves about teaching is grounded in listening to student voices, and in an approach to teaching that reflects thoughtfulness and humility. Attending to one’s teaching can be frustrating but it is enormously rewarding, and results in good feelings. We hope you have found that one good idea. We hope that something we said encourages you to think about your teaching in a new light, and to discuss these ideas 20 with others. We hope that throughout today and tomorrow, as we are immersed in teaching that a sense of community is created. We believe that it is the opportunity to share and learn from colleagues, and the sense of community that results, that sustain us in the complicated art and craft we call teaching. As we close, we urge you to check your worldly troubles at the door, and have a rewarding and fun conference. We are available throughout the conference to talk with you. It is our belief that any talk about teaching or student learning is time well spent. We thank you all for being here. Thank you. 21 Student Pet Peeves About Teachinga Na % Teaching Poor Organization/Planning 253 (17) Poor Teaching Mechanics (e.g., speak too fast/slow/softly, poor use of board) 207 (14) Lecture Style and Technique 154 (11) Poor Testing Procedures/Exams 121 (8) Monotone Voice 81 (6) Grading Process 50 (3) Lack of Interest/Competence/Depth, Lack of Course Content 36 (2) Unfair Grading 24 (2) Inappropriate Humor 18 (1) 944 (65)c Total Respect Intellectual Arrogance/Talk Down 44 (3) Don't Respect Students 42 (3) Not Approachable, Unhelpful 41 (3) Control/Impose Views 16 (1) 22 Intolerant of Questions 8 (1) Total 151 (10) General Poor Use of Class Time (coming late, 76 (5) stopping early) Not In During Office Hours/Hard to Find 35 (2) Poor Syllabus 33 (2) Forced Class Participation 28 (2) Insensitive to Student's Time Constraints 25 (2) Too Much Work 20 (1) Don't Relate Material to Real Life 12 (1) Bias/Sexism/Racism 2 (0) Other 34 (2) Total 265 (18) Negative Mannerisms Negative Mannerisms (e.g., attire, vocal and nonverbal mannerisms) Overall Total a This 95 (7) 1455 (100) table is from Perlman, B., & McCann, L. I. (1998). Student pet peeves about teaching. Teaching of Psychology, 25, 201-203.