Perlman, B., & McCann, L. I. (Spring, 1998). The Nuts... of Faculty Recruitment: Part II : The Campus Visit Through the

advertisement

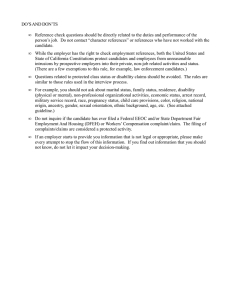

Perlman, B., & McCann, L. I. (Spring, 1998). The Nuts and Bolts of Faculty Recruitment: Part IIa: The Campus Visit Through the Search Completion. The Department Chair, 8(4), 16-17. In a previous article (Perlman & McCann, 199 -) we discussed organizing the recruitment committee, its initial tasks, developing a pool of candidates, screening, and selection of semi-finalists and then finalists. All of this work is a prelude for a campus visit by two or three of your top selections and a decision to offer a contract, continue, reopen or close the search. The Campus Visit Campus visits add to your knowledge about candidates, provide data on their personal dimensions, facilitate them getting to know you and your campus, and allow you to woo them and they you. Campus visits often solidify decisions and choices already made, but they can reveal poor fits between candidate and position or highlight personal traits which may make excellent teaching and scholarship problematic. They also may reveal department problems and issues which could influence candidates to reject an offer. During a campus visit be professional, ethical, warm, and organized. Honesty and candor are good policies which minimize the raising of false expectations. We suggest taking the following steps before candidates arrive. • Plan having one candidate on campus at a time. • Meet with your department colleagues to describe plans for the visits and to provide information. Urge them to avoid improper questions (e.g., age, marital status). • Contact the candidate about prospective dates, travel plans, lodging, and expectations for their visit (e.g., teaching a class and/or presenting a colloquium). • Ask about any special needs (e.g., dietary). • Send university and community materials prior to the visit. • Assign a shadow. This is the departmental member(s) who will be available to help and will accompany the candidate throughout the visit. • Expect the unexpected, from bad weather to illness. Once the candidate arrives it is imperative that time be used wisely. We recommend that the candidate be present during at least two days. Your goal is a campus visit which allows candidates to learn everything they want to know about the job and the community, and you to learn what you need to know about them. Prepare a printed campus visit itinerary. Identify individuals with whom the candidate will be meeting outside your department. Talk with the candidate about scheduling, preparation time before a colloquium, guest lecture or recital, early morning or late evening meetings, and so forth. Survey faculty and class schedules to identify the best times for a visitor's presentations and be assertive in asking colleagues and students to attend and to spend time with candidates. Get feedback from those who will not be attending the 3 department meeting when decisions on candidates will be made. If a candidate has a spouse or significant other be prepared for them to visit, and you may want to suggest that they do so (typically at their own expense). The best decision will be made if the spouse has complete information, and a campus visit helps ensure this. There is little down time during a visit. Even informal walks and unstructured conversations communicate important information. Have the candidate meet the departmental faculty individually or in small groups (e.g., recruitment committee, chairperson, other interested faculty, students). A mass meeting of a large department or interest group may be useful after both sides have become acquainted in earlier meetings, but these large gatherings yield little useful information for either candidate or faculty if held shortly after the candidate arrives. We do not recommend large social gatherings with department faculty and spouses. Have one of these early in the first semester your new colleague is with you. Sometime during the visit provide important logistical information to the candidate such as when a decision will be made, who makes an offer (e.g., department chair, dean), and how many other finalists are visiting. You also want to ask questions to gain important and useful information (e.g., how soon candidates can respond if offered a contract, current status of dissertation if not competed, whether they have current offers and any related deadlines for decision making, and where they can 4 be reached during the next few weeks.) Candidates also need to be introduced to your college or university. They often find it useful to meet with the Dean or Provost, a Grants officer, a Personnel officer, faculty in related departments, and representatives of your institution's mentor program and teaching development center. If there is a women's or minority caucus or interest group on campus, such candidates may want to meet with a representative(s). Finally, candidates will want an introduction to the community. While you are interviewing remember that not all of life involves work. Give a guided tour (e.g., housing, recreation, schools). Once a candidate leaves there is still work to do. If forms for travel, food, and/or lodging must be completed, designate someone (possibly your secretary) to be responsible for this, and put this item on the candidate's schedule. (The danger of being extremely efficient with the visit and reimbursement is that the candidate may come to expect that all business functions on your campus are equally well organized.) Send the candidate a thank you letter and determine via e-mail or phone call several days after their visit if there are questions that you can answer. Keep in touch. Conclude or Continue The Search: Hire, More Visitors, Reopen or Close It is now time to decide who, if anyone, will receive an offer. Some important decisions and work lie ahead -- to either 5 extend a contract, invite other finalists to visit, or reopen or cancel the search. The meeting to decide on offering a contract should have no other agenda items. Summarize the recruitment process at this meeting, the selection criteria used, and the reasons the visitors were chosen. Be specific and be careful. Many of the candidate dimensions discussed are not especially (nor legally) relevant to the selection process. Have complete information. Do not be surprised if you have to contact candidates with last minute questions prior to this meeting. Have candidate folders and transcripts available so faculty members can skim them, and so emergent questions or misinformation can be clarified. Throw the meeting open for discussion and debate and make sure everyone is heard. Do not hire someone, no matter how well he or she teaches, does research or performs, who will be unable to meet all criteria for contract renewal or tenure. Leave the meeting with a decision. Either you will offer someone the position, invite another finalist for a campus visit, reopen the search during this academic year or next, or close the search. When making an offer congratulations should be offered, your sincere interest conveyed, candidates informed of the exact nature of the position and general terms of employment, and how long they have to decide. Candidates often have important questions to resolve before they commit themselves. Be prepared for these questions. Telephone offers must be followed by written 6 letters tendering an offer within 10 days of informally offering a position (CCAS, 1992). The letter of offer constitutes a binding commitment and must be carefully written. Your department, college, and university will have established rules and protocols for who sends these letters and their content. Most candidates need time to respond to an offer; two weeks is appropriate. Never pressure candidates into premature decisions. If candidates try to hold you up unreasonably you must assertively define the conditions of the offer and let them decide. Keep communication timely and open. Remaining finalists should be contacted and told their exact status and your timetable and campus visitors must be thanked for their time and interest in your position and kept informed of their status. Stay focused on recruiting. You may feel you are done, but you are not. Many candidates are lost over a few hundred dollars of salary, moving money, or inability to purchase needed equipment. This loss makes little sense when you consider the time and cost which have gone into hiring the best possible person, and that this may be a million dollar, long-term decision. Never hire someone merely to get the search over with. Keep in mind that you can continue a search by reviewing active candidates' applications and extending invitations for campus visits. You may need to ask permission to reopen the search (enlarge the pool) this or next academic year, or close it. If 7 you do not have an acceptable candidate you may need to determine if the position was flawed (e.g., almost impossible to find the characteristics and experience you wanted) or the search process was flawed (e.g., began too late). If a candidate accepts, celebrate, and then finish the search. Provide needed information such as book order forms or copies of current syllabi) and prepare for your new hire's arrival [facilities and equipment (e.g., computer, office)], and complete your paperwork. a Baron Perlman and Lee McCann are Professors of Psychology, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. This article is based on material from their book, RECRUITING GOOD COLLEGE FACULTY, Anker, 1996. 8 References Council of Colleges of Arts and Sciences. (1992). The ethics of recruitment and faculty appointment. Columbus, OH: Author. Perlman, B., & McCann, L. I. (199-). The Nuts and Bolts of Faculty Recruitment, Part I: Forming the Recruitment Committee To Campus Visitors. The Department Chair, FINISH CITATION.