Surprise It is, in general, a bad idea to throw someone... the impetus almost always comes from a generous place, at...

advertisement

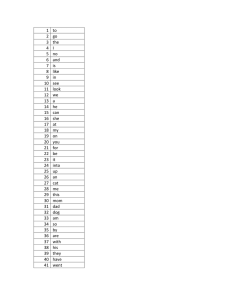

Surprise It is, in general, a bad idea to throw someone a surprise party. Even though the impetus almost always comes from a generous place, at the end of the day what you’re doing is assuring someone that while they may think they know what’s going on, they don’t. A whole flurry of activity has been rushing right beneath their radar and their friends, partner, and relatives have been looking them directly in the eye and lying to them—successfully. And yet, when my mother turned sixty, my sister and I threw her a surprise party. We never would have, but she asked for it. “No one ever throws me a party.” This had become a mantra for my mother. Whenver my parents returned from an anniversary party, retirement party, bas mitzvah, she would sink into her chair at the kitchen table and lament this truth. Perhaps she felt the lack so deeply because she valued ritual so much. Holidays, birthdays, all momentous occasions not only provided opportunites to dress up and go out; they also marked time and our place in it and this was, I think, important to my mother because she was anxious. At least that’s what she says whenever I ask her about my childhood. “Anxious?” I’ll ask. “About what?” “I was just anxious! You know, about everything.” I can only imagine what it must be like to feel inescapable chaos all the time—to need to impose order wherever possible. “Children need boundaries,” my mother was fond of saying, “so that they feel secure. And so my childhood was framed by an extensive list of guidelines. No satin in the summer, no leather in the winter, no white after labor day. Shoes had to be darker than your hemline, children were not allowed to wear black, wear makeup or finger nail polish. Underwear was not to be worn to bed; it doesn’t let you breathe. The full-time housekeeper was not allowed to make anyone’s bed. That’s your own space. You mess it up, you clean it up. No one was allowed out of bed before seven thirty in the morning. You could watch one hour of television on the weekdays but as much as you wanted on the weekends. Whatever was made for dinner was what the whole family was eating. You didn’t have to finish what was on your plate but you had to taste everything…every time it was made. No matter how convinced you may have been that you hated chicken liver, you had to taste it. You could help yourself to the vast array of snacks kept in “the yellow cabinet”—ding dongs, twinkies, Funions, snowballs—but no sugar cereals were allowed in the house because breakfast is a meal. Allowance was provided once a week but you could do no chores to increase your income because allowance wasn’t about what you did, it was because your parents love you. If you did something bad you were sent to your room and couldn’t come out until you learned your lesson, the proof of which entailed your readiness to come out, apologize and kiss the people who had put you in there. The longer my mother continued to sketch out a safe and comprehensible microcosm from which we could shine, the more obvious it became that no one was reciprocating. No one was recognizing her passage through time let alone watching her sparkle. So at the end of any festivity’s conclusion you could count on my mom to plunk down at the kitchen table in nothing but her bra, crack open a diet soda, and announce, “No one ever throws me a party.” The autumn of my mother’s sixtieth year, her birthday practically coincided with her twenty-fifth wedding anniversary and my father’s birthday as well. Three momentous occasions could be covered with one party. The bargain was too good to pass up. My sister and I organized from our respective homes in San Francisco and Colorado. On the Friday of the big weekend, I flew into LAX to find my mother standing at the gate like a trackstar at the starting line of the race. She’d been waiting for at least a half hour, smile steady, a hundred questions on the tip of her tongue. An onlooker might have thought my mother sensed the party of her dreams just around the corner, but I was long accustomed to my mother’s energy level. It was high. “New hair cut?” I asked before I even said hello. My mother is a beautiful woman. She has always stopped traffic with her looks and, because of that, she is invested in them. Blue eyes, perfectly manicured hands, an hour glass figure, a movie star smile. But the foundation upon which all of her vanity rests is my mother’s hair. If you want to get into my mother’s good graces, the first thing you need to do upon seeing her is tell her what you think of her latest style. I used to take such offense when I’d come home to visit from college and before a hug, a how are you, a hello, came “So?” followed by a beat of annoyedness while she waited. “What do you think of my hair?” It took me more than ten years to learn to start there. Mom,” I’ve learned to exclaim before setting down my carry-on. “I love your new cut.” “Really?” She’ll smile, her hands fluttering toward the top of her head for a moment of poking and prodding. “You like it?” she asked that afternoon, assuring me with the one question that I had my mother all figured out. Her reliability was practically Pavlovian and I felt pretty certain I could pull off this surprise with my eyes closed. I would have felt absolutely certain if not for my grandmother. “Your mother doesn’t like surprises,” she said when my sister and I described the ingeniousness, thoughtfulness, and overall brilliance of our plan. “Come on, Mama,” the two of us whined. “Everybody wants to have a surprise party thrown for them.” “Not your mother,” she said. We ignored this heeding—not because my grandmother was old or of out touch—but simply because we didn’t want to hear it. The idea that our mother thought she wanted something she really didn’t would turn her from omniscient, omnipotent ruler into innocent child. Plus I wanted her approval. Perhaps I was naive to imagine that a cynic could be transformed into an optimist overnight or that I could win my mother’s love by challenging her entire world view, but I believed deeply in the power of a good party. Happily, my mother’s best friend did too. The day after invitations were sent, Sheree Colvin was on my phone begging for the role of decoy. Sheree loved a project. At the time, she was learning Spanish, distressing furniture, and remodeling her back yard. Relatively speaking, a surprise party was small-time. Her husband, Dick was game as well. Instinctively I knew that Dick would be great working undercover. He rarely smiled or talked, but whatever he did say usually earned a laugh. He was the straight man to Sheree’s antics—willing, unpredictable, surprisingly funny. You’d never guess that he raced Apaloosa horses; you’d certainly never imagine him planning a party. Together, they made the perfect accomplice. We’d need a pretty intricate plan to keep my parents away from home on a Sunday afternoon if that’s where they wanted to be. They can behave a little bit like barn-sour horses—happy to trot along on weekend errands until suddenly they get a whiff of the Lakers game or the Havarti cheese lonely in the fridge. It took a few phone calls, but eventually, we concocted the perfect ruse. Sheree and Dick would feign interest in the Beverly Hills Country Club, referred to in my family as simply “the club,” and ask my parents to give them a tour. My parents have been members of the club since my sister and I were little. Back then it was called The Westside Raquet Club, a much more appropriate title since the club was neither in Beverly Hills, nor did it have the golf course required to qualify it as a country club. The club was less than five blocks away from our house and back when it was still the Westside Raquet, my sister and I spent virtually every weekend playing in the pool or laying on the hot clay and peeling it apart in big pink strips. In the late 80s, new owners decided to add a gym, resurface the pool, and the steps, and raise the rates. And so the Beverly Hills Country Club was born, complete with tattooed insignia on the bottom of the pool. Original members were given a discounted rate and, once initial resistance waned, a new sense of pride to belong to an organization that offered tennis matches between famous players and a fancy cobb salad you had to sign for to eat. While my sister and I mourned the loss of grungy afternoons pilling our swimsuits on the hot cement, my parents were happy converts and only too eager to welcome Dick and Sheree into the fold. The plan was for my sister to instruct guests where to park and usher them inside, and for me to keep my parents at the club, prolonging the tour for as long as she needed. The strategy seemed foolproof until my mother declined to come. She had scheduled a hair appointment that afternoon and cancelling was not an option. In an impromptu secret meeting, Sheree assured my sister and me that the haircut was, in fact, a blessing. My mom would be blissfully occupied for two hours at precisely the right time leaving only my dad to contend with. I felt edgy about leaving my mother unattended for so long but my confidence in the success of this event was immediately restored upon arrival at the club. Sheree was a natural. She oohed and aahed over everything from tennis court to locker room. She demanded every last detail. She sampled both the free coffee and the free tea. Dick contributed an occasional nod or sarcastic remark which failed to prolong the tour at all but lent a great deal to character credibility. Eventually, Sheree ran out of interesting questions and it became clear that my father was going to trade in his role of tourguide for an afternoon basketball game on the living room couch. “You know who I think would really like this,” Sheree said just as my dad was rattling his keys. “Jeffrey would really like this.” “Jeffrey?” my dad asked. “Jeffrey!” said Sheree. “Our son Jeffrey.” “Doesn’t he live all the way out in Hollywood Hills?” “But,” said Sheree, “I think he’d really really like this. I think he’d make the drive. Don’t you, Dick?” “Let’s call him,” said my father. And presto, just twenty minutes later, Jeffrey was standing on the balcony beside us, watching the insignia of the Beverly Hills Country Club waver in the sky blue water. “Can you pick your membership number?” he asked. “How’s the food?” I excused myself to use the bathroom and instead used the bar telephone to call my parents’ house. “How’re things going over there?” I asked in a hurried whisper. “We’re getting a little desperate over here.” They were ready. All I needed to do was get my dad there and my mom, at the same time. Panic rippled through my skin. When I returned to the balcony, all I could do was meet Sheree’s raised eyebrows with a curt nod. Happily, thankfully, Dick kicked into action. “Okay,” he said, clapping his hands together. “Let’s go.” My father had not completed his speech about family membership policies. “Jeffrey,” he said, concerned, “are you ready?” Jeffrey nodded. “I actually need to go,” he said. “I have to…be somewhere.” “Bob,” Dick said. “Is Caroline’s beauty appointment about done?” My father looked totally bewildered. “Her hair,” Dick said, seemingly exasperated. “Shouldn’t she be getting out of her appointment soon?” I looked at Dick, unsure where he was heading. “We should pick her up,” he said. Even though the club was a mere five minutes’ walk from home, my parents always drove there. No sense in tiring themselves before a workout. “We can all climb into your car,” Sheree said, “and pick her up together.” “Oh she’s fine,” my dad said. “She likes to walk.” It was true. Once a month my mother walks down the hill in the opposite direction of the now-Beverly Hills Country Club to the strip mall by the 10 East onramp for a cut and color at Pink Nails. My father hates this strip mall. The parking lot is filled with homeless people and rusted cars parked so close together, getting out of there without a ding in your door is an artform. And, to make matters worse, upon pulling out of the Pink Nails parking lot, before you can turn the corner into suburbia, you must first pass this clump of rotting over-populated apartments where my father claims there are so many children spilling into the street, it’s only a matter of time before you hit one. For this reason, he has affectionately dubbed this spot “Dead Kid Corner.” “Never speed around here,” he said the summer I turned sixteen. “This may be the most dangerous spot in all of L.A.” But my mother has been going to this same hairdresser in this same stripmall for more than fifteen years. Sandwiched between Subway and a Wells Fargo ATM, the salon doesn’t look like much from the outside. It really doesn’t look like much from the inside either. To my mother, this is an asset. She isn’t cheap; she’s offended by boutiques, challenging that virtually all specialty services and products can be found for half the price and twice the quality at COSTCO. But COSTCO doesn’t cut hair and so my mother has Fernando. My mother never sounds happier than when she is calling from Fernando’s chair—arguments flying, scissors twirling, hairdryer whirring. The calls never last more than a minute, the front of checking-in employed to mask her impulse to share the joy she cannot contain. My mother loves getting her hair done. My father knows this and his inclination to let her take her time walking home did not show a lack of chivalry so much as a deep understanding of his wife. “I would never let Sheree walk home all alone,” said my dad. “Really?” my dad said. “Past the freeway onramp?” Dick said, seemingly horrified. “Hell no! Bob!” My dad shrugged. “Okay,” he said, and we all piled into the Cadillac. Less than ten minutes later, my father had disappeared into Pink Nails and we sat giggling like school kids in the backseat. We had barely finished high fiving each other before he returned, alone. “Fernando wasn’t there,” my dad said. “He didn’t show up so they just washed her hair. “Oh no!” Sheree’s hand flew to her mouth. “It’s all right,” my dad said, adjusting his sunglasses. They let her go about five minutes ago. She’s probably just about home.” Dick’s reaction was sudden and strong. “No!” he shouted. “Bob! There’s still time! We can catch her.” “She’s really fine,” my dad assured. “She walks home from Fernando’s all the time.” “Not with a wet head!” Dick was trembling in his excitement. “Go, Bob! Go! Let’s see how fast you can make this tin can move!” Whatever hairline trigger he’d pressed snapped in my father and suddenly there we were, blaring across Motor Avenue, screeching around Dead Kid corner, heads and hands hanging out the windows in search of my mother, the hope of scooping her into the car before she walked her seven blocks home vibrantly alive. “Is that her?” Dick asked. He leaned over my father and onto the horn. It wasn’t. My mother reached home a solid ten minutes before us. I knew before anyone told me. The paralyzed party of people standing in my parents’ living room showed clearly enough that she had arrived and things had not gone as planned. We’d walked through that front door to a seeming wax museum of my parents’ friends, and a full minute passed before anyone was able to recover, look my father in the eye and shout, “surprise.” My dad broke into immediate laughter. “This is great!” he shouted. He looked at me. “This is great!” I found my sister in the crowd. She was shaking her head. “Not good,” she mouthed. A gaggle of women flocked around me, patting my head and my hands as they offered snippets of my mother’s reaction. My sister finally took me by the wrist and led me into the hallway. “It was a disaster,” she said. “Fernando didn’t show up but Mom had walked all the way there so they just washed her hair, no blow dry, and sent her home. Wet head, no makeup. It was bad.” “What brand of bad?” “She pretty much put her hands to her head, screamed ‘No!’ and went running for the bedroom.” “Have you been in there?” I asked. “I’m not going in there,” she said. “Okay. You try to calm everyone down and I’ll go in there.” Through the living room’s sliding glass door I could see the party picking up speed. My dad, already with a drink in hand, was headed over to the bbq to check out the spread and mind the grill. “Did you see his face?” I heard someone ask. “Did you see hers?” I walked down the hall in a state of surprising calm. I still could not accept the idea that things hadn’t panned out as planned. Address books had been stolen, liquor had traveled, COSTCO had provided all the bbq essentials mere hours before the party started. Just thinking about it made me puff up like a pigeon with pride, even though I knew that behind my parents’ bedroom door was living proof we’d failed. As my hand reached for the knob, my grandmother’s voice reverberated in my mind. “Your mother doesn’t like surprises.” She was sobbing in the bathroom. Her shaking hand barely able to wield her hairdryer. “Look at me!” she shrieked. “Look at my hair” She stalked from bathroom to bedroom so beside herself she didn’t think of the guests in her yard all able to see through the French doors. “You didn’t eve make my bed!” she said. I hadn’t heard Sheree enter the room but now her hands were on my shoulders. “Go on, honey,” she said. “Go on out to the party. Let me help your mother fix her hair.” Muffled sobs and cooing seeped through the closing bathroom door and I crossed the house by myself. Everyone had migrated to the backyard, and through the living room’s glass doors I stood watching my sister attend to both the laughing and the uncertain guests, flagellating myself for refusing to listen to my grandmother’s warnings; for crossing the boundaries of my mother’s house—not making the bed, making this mess with no idea how to clean it up. Seeing them, unable to hear them, I felt truly alone and worthy of hate. I knew nothing, least of all how to love someone. I was ready to pack up, fly home, and go fetal for week or two. But then, after twenty-seven years of slow blooming, I grew up in an instant. She came out of her room, where I had sent her running with the tragic urgency of a child, and found me, put her arms around me, kissed me on the cheek and said “I’m sorry. I was wrong. Thank you.” My mother turned from me then and faced the crowd of expectant guests, glided through the sliding glass doors and into the backyard like a newly crowned beauty queen, a prize fighter, an actor returned to the roaring applause of the crowd. And while she stood glittering with freshly blown hair and her movie star smile, time stood still. I stood in the empty living room feeling her kiss dry on my cheek, a silent dictator surveying the crowds.