Public Opinion

advertisement

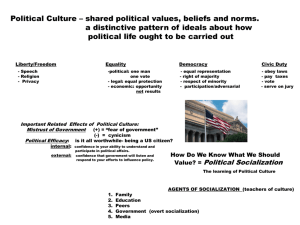

Public Opinion When attempting to analyze the role of public opinion in the policy-making process, it is important to first establish a precise definition of the concept. This is accomplished by breaking public opinion into its components and defining first what is meant by public and second by opinion. Public - a collection of individuals who share a common attitude This definition suggests that there is no single public. The idea of the general public has very little use to us in the study of public opinion. Consider that, on any given issue [electoral or policy issues], the general public can be divided into: [1] an apathetic public - the collection of individuals who are not paying attention to the issue and who do not express their attitudes in any meaningful way; [2] an attentive public - the collection of individuals who are at least paying attention to the issue and who may express their attitudes in a meaningful way; and [3] a mobilizible public(s) - the collection of individuals who are paying attention to the issue and who do express their attitudes in a meaningful way. The relative sizes of the apathetic, attentive, and mobilizible publics vary according to the visibility of the issue. Generally, though, as the visibility of the issue diminishes, the size of the apathetic public increases and the sizes of the attentive and mobilizible publics decrease. Presidential elections Apathetic public Some less visible issue Attentive/mobilizible public Apathetic public Mobilizers [activists] Mobilizers [activists] Attentive/mobilizible public The diagram on the left suggests the relative sizes of these publics on the most visible of all issues, presidential elections. In elections, the attentive and mobilizible publics are essentially the same. As issues decrease in visibility then, we would expect to observe the effect described above and illustrated in the diagram to the right. Since only mobilizible publics express their attitudes in a meaningful way, only their opinions influence policy-making. To put the matter another way, government cannot respond to attitudes that are not expressed. Additionally, it should be noted here that there are three distinguishable types of mobilizible publics: • single-issue publics - a collection of individuals who are attentive to and mobilizible on one issue or a narrow range of issues; • organizational publics - a collection of individuals who are attentive to and mobilizible on issues that impact the organization or its membership [the defining characteristic of this type of public is the presence of a formal organization]; • ideological publics - a collection of individuals who are attentive to and mobilizible on any issue that relates to its ideology. An ideology (used loosely in this context) refers to a set of political, social, economic, religious, moral, ethical, or civic principles, ideals, or values. The main point to be emphasized in this discussion of “public” is that there is no single public. Any definition of public opinion must incorporate this fact if it is to be of much use in understanding the relationship between public opinion and public policy. Opinion - an opinion is an expressed attitude. The key to this definition is the word “expressed.” An attitude stands little chance of impacting policy-making unless it is expressed in a way that is meaningful - that is, in a way that can be processed by the political system. Defining public opinion - We can synthesize a useful definition of public opinion: public opinion is the shared expressed attitudes of a collection of individuals on a matter of common concern. “Meaningful” Ways of Expressing Attitudes - four general means are open to any public that wishes to express its attitudes on an issue: [1] voting in elections - “send the politicians a message” [2] direct communication - town meetings, traditional lobbying, etc.. [3] organized group activities - protests, demonstrations, strikes, petition drives, “grassroots lobbying” [4] public opinion polling - reliability/validity issues [survey design, question wording, sampling techniques, margin of error, etc..] Characteristics of Public Opinion - There are a number of characteristics of public opinion which may, depending on the issue, affect the response of government: • distribution - refers to the numerical strength (usually expressed as a percentage or ratio) of the various opinions held on an issue. For example, when we say that 40% of survey respondents support position X, 35% support position Y, and 25% support position Z, we are referring to the distribution of opinions on the issue. Distribution is the most important characteristic of opinion on electoral issues; it may be less important on policy issues. In other words, in elections, it is the distribution of opinions [rather than any of the other characteristics listed below] that determines the response of the political system [output]. If candidate A receives 49% of the vote, candidate B receives 42%, and candidate C receives 8% of the vote, then the distribution determines the response - A wins! Frequently, it is useful to graphically depict the distribution of opinions on an issue - we can graph the distribution to get a picture of what it looks like. Distribution of opinions, then, is like the distribution of anything else: wealth, grades, etc.. • intensity - this refers to the strength of feeling with which a public holds its attitude [or the level of commitment a public has to its position]. Public opinion polls generally report only the distribution of opinions on an issue. Even when surveys are designed to give respondents options to express how intensely they “feel” on an issue, there is no attempt made to determine how mobilizible their opinions are. Intensity, in this context then, refers to the strength of feeling as it affects a public’s willingness to mobilize. It may be that, on some issues, government makes public policy consistent with the opinions of small, but intense (highly mobilized) minority publics rather than the opinions of large, but lethargic (not mobilized) majority publics. • stability - Stability refers to both the distribution and intensity of opinions over time. On some issues, these are relatively stable (i.e..., gun control, abortion). On other issues (particularly electoral issues), however, opinion can be rather unstable, shifting dramatically sometimes over a short period of time. Judicious decision-makers may want to know something about the stability of opinions before embracing a particular policy alternative or associating himself with a candidate for another office. • latency - Opinions may exist merely as a potential. Latency refers to a characteristic of opinions that have not yet been crystallized. Latent opinions relate to attitudes not about any specific issue but concern general assessments about direction (i.e.., “Is the country, state, or city headed in the right direction?”). These are called valence issues. Valence issues are most relevant to assessments of leadership performance. Frequently, valence issues (and latent opinions) are more important than specific issues in dictating the political fortunes of presidents, governors, and mayors. For example, Bill Clinton won re-election in 1996 largely because voters generally believed the country was headed in the right direction, despite persistent questions about Mr. Clinton’s character. Similarly, Ronald Reagan won re-election in 1984 largely because of favorable ratings on leadership even though polls showed that majorities of Americans disagreed with the president on important specific issues. George Bush and Jimmy Carter were defeated in their re-election bids largely because voters sensed that “something (nonspecific) was wrong.” Polls did not indicate widespread disagreement with either president on specific policy issues. • salience - Salience refers to the extent to which a particular issue affects a given public. To what degree does an issue “connect” for a public? Some issues are salient for a public and others are not. The salience of an issue seems likely to affect the previously-indicated characteristics of opinion (distribution, intensity, stability)? What Have We Learned From Public Opinion Research? Public opinion research can tell us much about the distribution, intensity, stability, latency, and salience of opinions on specific issues or specific leaders. We could spend much time detailing the findings of such research. In a more general vein, however, public opinion research over the past four decades has revealed four major trends: • Support for the political system remains fairly high among Americans, particularly when compared with the levels of support expressed in other (even democratic) countries. This support is expressed in a number of ways: patriotism, respect for democratic processes and institutions, attachments to political symbols (flag), and comments such as “It’s not a perfect system, but its the best!” This diffuse support is critical to the long-term maintenance and stability of the political system. [See handout entitled “Political Socialization.”] • Levels of political knowledge are generally low. Americans seem to understand little about the operation of their political system, its institutions, processes, and officials or about the important issues facing their nation, states, or cities. Majorities cannot identify their representatives in Congress. How can such low levels of basic political knowledge be reconciled with high levels of support for the system? • Feelings of political efficacy are generally low. Efficacy refers to the sense that a person has that what he or she thinks or does will have an effect on what government does. Low levels of efficacy are expressed when Americans say things such as “Why should I bother to vote? The politicians don’t care about people like me anyway.” Low levels of efficacy are not universal. Political scientists are quick to point out that the degree of efficacy expressed by Americans is largely a function of their income and educational levels, as well as other demographic characteristics such as ethnicity and gender. How can generally low levels of efficacy be reconciled with generally high levels of support for the system? Are low feelings of efficacy among Americans consistent with the relatively low levels of political knowledge they demonstrate? • The degree of political trust has eroded dramatically. Over the last several decades, public opinion polls have shown that fewer and fewer Americans believe that they can trust government to do the right thing. [See Table 7.2 on p. 240 of American Government and Politics Today.] Are low levels of trust in government consistent with high levels of support for the political system? ....low levels of political knowledge? ....low levels of political efficacy? Public Opinion When attempting to analyze the role of public opinion in the policy-making process, it is important to first establish a precise definition of the concept. This is accomplished by breaking public opinion into its components and defining first what is meant by public and second by opinion. Public - a collection of individuals who share a common attitude Presidential elections Apathetic public Some less visible issue Attentive/mobilizible public Apathetic public Mobilizers [activists] Mobilizers [activists] Attentive/mobilizible public Types of Mobilizible Publics •single-issue publics •organizational publics •ideological publics Opinion - an opinion is an expressed attitude. Public opinion - the shared expressed attitudes of a collection of individuals on a matter of common concern. “Meaningful” Ways of Expressing Attitudes [1] voting in elections [2] direct communication [3] organized group activities [4] public opinion polling Characteristics of Public Opinion •distribution •intensity •stability •latency •salience What Have We Learned From Public Opinion Research? •high levels of support for the system •low levels of political knowledge •low levels of political efficacy •eroding levels of political trust Political Socialization - The Macro Process Diffuse support is critical to the maintenance and stability of the political system A political system must be able to generate or create diffuse support How? -coercion or force -manipulation of values/propaganda (hegemonic theory) -socialization (systems theory) Systems theory argues that values in support of the political system are transferred through a generational process, wherein the family teaches values that will allow the child to succeed in society. These values are reinforced by other important agents of the socialization process. Agents of socialization: • parental family 1. direct value transfer [values having a direct political context]: party id, policy ideals 2. indirect value transfer [values having an indirect political context]: conformity, respect for authority figures, competition for rewards, gender roles, moral values, religious values, self-reliance, work ethic, thrift, other economic values, etc. [these may vary according to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic class, etc.] • schools and the educational system 1. direct value transfer: curriculum (idealized forms), texts, pledge of allegiance, etc. 2. indirect value transfer: conformity, respect for authority, competition for rewards, democratic decision-making, citizenship, etc. [these may vary according to the clientele of the school] • peer groups Political Socialization - The Micro Process In order for the political system to convert specific demands in public policy outputs, it must have support. The political system must be able to generate and sustain support if it is to remain stable. Perhaps the most important way to accomplish this objective is to instill favorable attitudes in people toward the symbols of the system. This process may be overt and orchestrated as hegemonic theory suggests or it may be a natural, generational process as systems theory argues. Through the processes of socialization we learn about our culture - its norms, traditions, values, and acceptable patterns of behavior. Political socialization is the process in which each of us learns about the political culture -that is, political norms, traditions, values, and acceptable patterns of political behavior. Through political socialization, people acquire attitudes and orientations toward the politics of their societies. Socialization is important because it usually teaches values and norms that support the system. If it is successful [at a “macro” or systems-wide level] it produces the broad, diffuse support that is critical to the stability of the political system. Socialization also [at a “micro” or individual level] is the process whereby each member of society comes to form his or her own specific set of political attitudes, values, beliefs, orientations, and opinions. Therefore, while the socialization process has some basic similarities for all members of society, there may be variations on the process for particular groups or sectors of society and for individuals. There are three major phases of the socialization process : childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. While socialization takes place throughout a person’s lifetime, some phases are critically important in shaping socialization at both the “macro” and “micro” levels. The primacy principle argues that the values that we learn earliest in life are the ones that form the core of our value systems when we become adults. For most of us, these values remain with us througout our entire lives. The structuring principle means that the values that we learn earliest in life help us “structure” or assimilate new and ,sometimes, competing information into our existing value systems. These two corrollary principles suggest that childhood, even very early childhood, is critical in the process of successful political socialization. They also imply that the most important agent of the political socialization process is the parental family.