Paper Chase China's Reporters Face a Backlash Over Investigations

advertisement

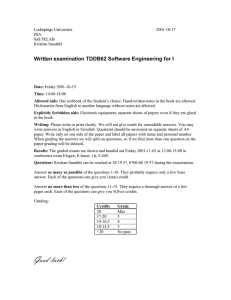

PAGE ONE Paper Chase China's Reporters Face a Backlash Over Investigations As Journalists Push the Limits, Government Cracks Down On Muckraking Stories The Case of the Killer BMW By GEOFFREY A. FOWLER and JASON DEAN December 21, 2006; Page A1 BEIJING -- In a country where media censorship is national policy, Liu Jianqiang has pulled off some remarkable journalistic scoops. When a wealthy socialite struck and killed a farmer with her BMW in northeastern China three years ago -- and then got off with a slap on the wrist -- it was Mr. Liu, an investigative reporter from out of town, who dug deep into the case. Local reporters who had been hushed up by government officials passed him information on irregularities in the way prosecutors handled the trial. The result was a widely read story that suggested corruption influenced the verdict. Within days of the article's publication, the government ordered an official investigation. A prosecutor in the case was later convicted of receiving bribes on the BMW and other cases, and sentenced to six years in prison. "There are people who don't want things to come out," says Mr. Liu. "But there are always other people who do." Today, China's government is waging a media crackdown on such hard-hitting reports. Some officials fear that investigative reporting feeds public discontent over social ills such as rampant pollution, a growing wealth gap, and especially corruption. Prominent editors at publications around the country have lost their jobs. A law under review in China's legislature could make it much more difficult for reporters like Mr. Liu to investigate emergencies and dig up wrongdoing in distant towns and villages. Mr. Liu's journalistic successes and the pressure he and his peers now face reflect the Chinese leadership's deep ambivalence toward the press. Journalists have become an effective tool for rooting out corruption, one of China's most intractable problems. They also unnerve Communist Party rulers fearful of unrest and any challenge to their authority. In September the party ousted one of its highest-ranking members, Shanghai party secretary Chen Liangyu, as part of a probe into misuse of the city's $1.2 billion pension fund. The dismissal of Mr. Chen followed in-depth stories in several publications about the involvement of Mr. Chen's allies in the scandal. For years, the government treated newspapers and TV stations -- all of which were at least partly state-owned -- as propaganda vehicles, and profitability wasn't a priority. Typical front-page news included tedious recitations of party leader speeches and profiles of model communist workers. But as China's economic reforms gathered steam a decade ago, the government began cutting subsidies to media outlets and subjecting them to market forces. Many print media groups, increasingly forced to fend for themselves, produced commercial titles to draw readers and tap China's booming ad industry. At the same time, the party began officially encouraging watchdog journalism by state-run media outlets under the rubric "supervision by public opinion." The changing atmosphere prompted some news outlets to pump up their investigative reporting, which quickly won over readers eager for an alternative to bland propaganda. Southern Weekend, the newspaper where Mr. Liu made his name, was among the first to make that shift. In 1992, the party-controlled Nanfang Daily Group transformed what had been a four-page entertainment newspaper into a hard-hitting weekly covering national news. It won more than a million readers, and advertising dollars flowed in. The paper, based in the booming southern city of Guangzhou, became famous for edgy interviews, such as one published in 2001 with members of a gang that had killed 28 people in a spree of murder and theft. The story analyzed the role of poverty in gang violence, and challenged China's growing inequality. Farmer Dai Yiquan, top, helped a Chinese newspaper probe the 2004 case of his wife, who was hit and killed by a BMW, above. China's censors still wielded the authority to block sensitive stories about corruption and wrongdoing, and some topics -- such as direct criticism of senior leaders -remained strictly off limits. But journalists at Southern Weekend and other publications found loopholes. One of the most effective ones involved reporters digging for news in distant parts of the country, away from their own censors. China's censorship often relies on local officials using their influence over the local press. Out-of-towners escaped their reach. The practice of sending reporters to investigate wrongdoing in other locations became known as yidi jiandu, or "cross-regional supervision." Journalists exploiting this regulatory gray zone helped expose such problems as China's massive rural HIV/AIDS crisis, which devastated the countryside in Henan province. Aggrieved farmers and families of mining-disaster victims began seeking out journalists. Some papers, including Southern Weekend, set up special hotlines for calls from readers with grievances and story ideas. The growth of the Internet also helped enterprising reporters sniff out stories or get them published by faraway newspapers. Local government officials in provinces all around China soon feared visits from out-of-town reporters, especially from Southern Weekend. One of the paper's most aggressive news hounds was Mr. Liu, now 37 years old. During his childhood in rural Shandong province, China didn't have any investigative journalists. His father, who had worked in a small municipal waterworks, was banished with the rest of the family to the countryside during the decadelong Cultural Revolution that began in 1966. With no books in the house, Mr. Liu learned to read using the only written material available -- self-criticisms his father was forced to write for his purported political offenses. In college, Mr. Liu studied Marxism and then went to work for a bank. Bored with his job, he took a writing test for his local Communist Party newspaper, and landed a reporting job in 1997. The work wasn't as exciting as he had hoped. "I would follow party leaders and write that they went to a place and had a very important speech," he says. In 2000, Mr. Liu joined a journalism program at Tsinghua University, one of China's top schools. There, he began to read overseas newspapers. He studied the Pulitzer Prizes. "My whole world changed," he says. "I learned what real news was." After completing his master's degree in 2003, Mr. Liu found a job in the Beijing bureau of Southern Weekend. There, his editors got wind of the BMW incident. Local journalists in Harbin, a major city in the northeast, had been filing uncritical stories on the trial of the wealthy driver. Then, Chinese Internet forum users and bloggers began commenting on the case, raising its national profile. Mr. Liu went to Harbin to investigate. He says he set up lunch with local journalists, some of whom "had information they could share, but had been instructed by the local propaganda department not to do so." One journalist hinted to Mr. Liu that the trial was flawed, and passed him a videotape of the court proceedings. Mr. Liu took a taxi to the tiny village where the victim's husband lived. But the husband, Dai Yiquan, didn't want to talk about the accident. As Mr. Liu tried to put him at ease, another farmer pulled up in a tractor with a machine to grind corn into feed. Mr. Liu, familiar with such chores from his childhood on a farm, offered to help Mr. Dai. Several bushels later, Mr. Liu had won Mr. Dai's trust, and a major lead on the story. The husband, it turned out, had told police that the BMW driver had shouted and cursed at the couple before the collision, and had tried to hit him with her car before striking his wife. This belied the defendant's claims that the incident was a simple accident. Back in town, Mr. Liu found a judge -- a friend of a friend -- who helped him review the videotape of the court proceedings. They found that the prosecutor never introduced Mr. Dai's recounting of the driver's verbal assault, nor his allegation that the collision was intentional. The judge told Mr. Liu this omission was a violation of Chinese court procedure. Mr. Liu's story ran in the following week's Southern Weekend. The headline read: "Harbin's 'BMW-Hits-Pedestrian' Case Clouded by Doubt: Numerous Problems Emerge in Legal Procedures." Two officials connected with the case were eventually removed from office. One, a prosecutor named Pang Jiulin, was convicted in August of 2004 of corruption for having taken $10,125 in bribes in the BMW and other cases. He was sentenced to six years in prison. Zhang Yanbin, another local official, was dismissed in July for taking a $1,012 bribe. The court report said that the BMW bribe was from the driver's family, but never said who was doing the bribing in the other cases. The provincial propaganda department office declined to comment on the case. Messrs. Pang and Zhang couldn't be reached for comment. Mr. Liu later scored other journalistic coups. A front-page story he wrote last year helped prompt the government to abandon a project to seal the bottom of a Beijing lake after showing that the project was destroying the surrounding ecosystem. It won him an environmental reporting prize sponsored by DuPont Co. After he wrote a piece about an HIV prevention program for sex workers in Yunnan province, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation paid for him to attend the International AIDS Conference in Toronto. But outwitting the system through yidi jiandu soon got a lot tougher for Mr. Liu and his colleagues. In the summer of 2005, Mr. Liu landed what he thought was another big scoop: a tip, he says, that the deputy governor of Henan province was being investigated for conspiring to have his wife killed. Mr. Liu called the police for comment. "I knew that the story was sensitive and if I got one little thing wrong, they would use it to come after me," he says. When he called at 10:00 a.m. the day before the story was to run, police confirmed the case existed, but said they were still awaiting instruction from authorities on how to talk about it, Mr. Liu says. That afternoon, the propaganda department of Guangdong province, Southern Weekend's home, called Mr. Liu's editors and told them not to run the story, he says. He believes the call came because the Henan propaganda department asked the central government to intervene in the case. The Guangdong and Henan propaganda departments didn't respond to a request for an interview. Only months later did China's high court release rudimentary details of the case. In October of 2005, the vice governor was sentenced to death for the murder of his wife, according to the court's official Web site. The incident was a sign of bigger problems. As muckraking stirred up public angst, government officials grew frustrated. "The central government is using the media as a watchdog," says Li Xiguang, executive dean at the School of Journalism and Communication at Tsinghua University. But officials are also "very much worried about mistrust of the public toward the government." In particular, the increasingly freewheeling media were criticized by some outside the government for shoddy journalistic practices. "Commercial pressure seeks readers, and people love negative news," Mr. Li says. Such criticism resonated with the administration of President Hu Jintao, who has made building a "harmonious society" a big priority since he took office in 2003. Last fall, the government stepped up its curbs on the Internet and fired or censured several prominent editors. The central government also issued a guideline calling for an end to "cross-regional supervision" reporting. When Southern Weekend's top editor heard the news, he held a somber staff meeting. "Everyone felt helpless," says Ruichun Yang, at the time Southern Weekend's page-one editor, who adds: "If yidi jiandu ends, so does watchdog journalism." Soon after, three of the weekly's front-page stories were yanked before they went to press, says Ms. Yang. The guidance against yidi jiandu doesn't yet constitute Chinese law, and Southern Weekend still sends its staff to report in other provinces. But editors think twice now before doing so. Today as many as one in five of Southern Weekend's big stories end up getting axed, and many more ideas are killed before they're even reported, Ms. Yang says. Officials at Nanfang Daily Group, Southern Weekend's owner, didn't respond to a request for an interview. A frustrated Mr. Liu took a sabbatical last April to write a book about Tibetan culture, and returned only this month. He and other Chinese journalists say they haven't given up. "Even with the restrictions on political reporting, there is a lot of room for Chinese journalists to write meaningful articles," Mr. Liu says. Last summer, China's legislature began debating a proposed law that would make yidi jiandu harder, by enabling heavy fines against journalists who report news without the authorization of local governments. But in a surprising show of defiance, some newspapers and magazines condemned the draft law almost immediately after lawmakers began considering it in June. The proposal remains under discussion. -- Juying Qin in Hong Kong contributed to this article. Write to Geoffrey A. Fowler at geoffrey.fowler@wsj.com and Jason Dean at jason.dean@wsj.com