Mood Disorder Recognition in Rural Primary Care: INTRODUCTION RESULTS

advertisement

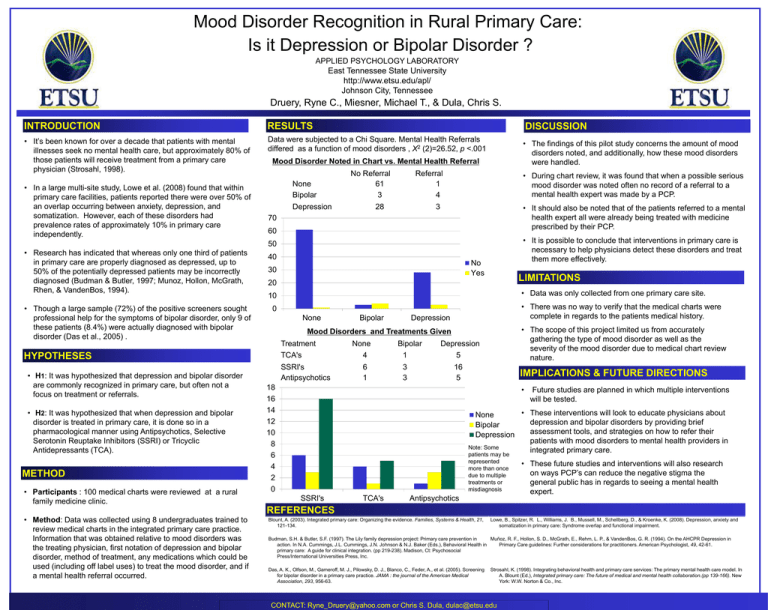

Mood Disorder Recognition in Rural Primary Care: Is it Depression or Bipolar Disorder ? APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY LABORATORY East Tennessee State University http://www.etsu.edu/apl/ Johnson City, Tennessee Druery, Ryne C., Miesner, Michael T., & Dula, Chris S. INTRODUCTION RESULTS DISCUSSION • It’s been known for over a decade that patients with mental illnesses seek no mental health care, but approximately 80% of those patients will receive treatment from a primary care physician (Strosahl, 1998). Data were subjected to a Chi Square. Mental Health Referrals differed as a function of mood disorders , X2 (2)=26.52, p <.001 • The findings of this pilot study concerns the amount of mood disorders noted, and additionally, how these mood disorders were handled. • In a large multi-site study, Lowe et al. (2008) found that within primary care facilities, patients reported there were over 50% of an overlap occurring between anxiety, depression, and somatization. However, each of these disorders had prevalence rates of approximately 10% in primary care independently. Mood Disorder Noted in Chart vs. Mental Health Referral None Bipolar No Referral 61 3 Depression Referral 1 4 28 • During chart review, it was found that when a possible serious mood disorder was noted often no record of a referral to a mental health expert was made by a PCP. • It should also be noted that of the patients referred to a mental health expert all were already being treated with medicine prescribed by their PCP. 3 70 60 • It is possible to conclude that interventions in primary care is necessary to help physicians detect these disorders and treat them more effectively. 50 • Research has indicated that whereas only one third of patients in primary care are properly diagnosed as depressed, up to 50% of the potentially depressed patients may be incorrectly diagnosed (Budman & Butler, 1997; Munoz, Hollon, McGrath, Rhen, & VandenBos, 1994). • Though a large sample (72%) of the positive screeners sought professional help for the symptoms of bipolar disorder, only 9 of these patients (8.4%) were actually diagnosed with bipolar disorder (Das et al., 2005) . 40 30 • H2: It was hypothesized that when depression and bipolar disorder is treated in primary care, it is done so in a pharmacological manner using Antipsychotics, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) or Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCA). METHOD • Participants : 100 medical charts were reviewed at a rural family medicine clinic. • Method: Data was collected using 8 undergraduates trained to review medical charts in the integrated primary care practice. Information that was obtained relative to mood disorders was the treating physician, first notation of depression and bipolar disorder, method of treatment, any medications which could be used (including off label uses) to treat the mood disorder, and if a mental health referral occurred. LIMITATIONS 20 • Data was only collected from one primary care site. 10 • There was no way to verify that the medical charts were complete in regards to the patients medical history. 0 None Bipolar Depression • The scope of this project limited us from accurately gathering the type of mood disorder as well as the severity of the mood disorder due to medical chart review nature. Mood Disorders and Treatments Given Treatment TCA's HYPOTHESES • H1: It was hypothesized that depression and bipolar disorder are commonly recognized in primary care, but often not a focus on treatment or referrals. No Yes SSRI's Antipsychotics None 4 6 1 Bipolar 1 3 3 Depression 5 16 5 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 IMPLICATIONS & FUTURE DIRECTIONS • Future studies are planned in which multiple interventions will be tested. • These interventions will look to educate physicians about None depression and bipolar disorders by providing brief Bipolar assessment tools, and strategies on how to refer their Depression patients with mood disorders to mental health providers in Note: Some integrated primary care. patients may be represented more than once due to multiple treatments or misdiagnosis SSRI's TCA's Antipsychotics • These future studies and interventions will also research on ways PCP’s can reduce the negative stigma the general public has in regards to seeing a mental health expert. REFERENCES Blount, A. (2003). Integrated primary care: Organizing the evidence. Families, Systems & Health, 21, 121-134. Lowe, B., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Mussell, M., Schellberg, D., & Kroenke, K. (2008). Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: Syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Budman, S.H. & Butler, S.F. (1997). The Lily family depression project: Primary care prevention in Muñoz, R. F., Hollon, S. D., McGrath, E., Rehm, L. P., & VandenBos, G. R. (1994). On the AHCPR Depression in action. In N.A. Cummings, J.L. Cummings, J.N. Johnson & N.J. Baker (Eds.), Behavioral Health in Primary Care guidelines: Further considerations for practitioners. American Psychologist, 49, 42-61. primary care: A guide for clinical integration. (pp 219-238). Madison, Ct: Psychosocial Press/International Universities Press, Inc. Das, A. K., Olfson, M., Gameroff, M. J., Pilowsky, D. J., Blanco, C., Feder, A., et al. (2005). Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association, 293, 956-63. Strosahl, K. (1998). Integrating behavioral health and primary care services: The primary mental health care model. In A. Blount (Ed.), Integrated primary care: The future of medical and mental health collaboration.(pp 139-166). New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc. CONTACT: Ryne_Druery@yahoo.com or Chris S. Dula, dulac@etsu.edu