Updates in Treatment of Hepatitis C Gene LeSage, MD, FACP, AGAF

advertisement

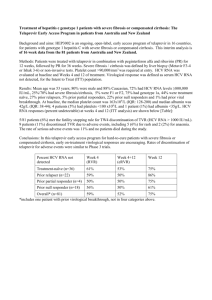

Updates in Treatment of Hepatitis C Gene LeSage, MD, FACP, AGAF Objectives • HCV epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and prognosis • Interferon (IFN) and Ribavirin (RBV) based therapy • Direct acting anti-viral (DAA) therapies HCV Epidemiology • Nearly 3% of worldwide population has chronic HCV infection[1,2] – Most common blood-borne infection in United States[3] • Up to 75% unaware of HCV infection until liver disease or cancer develops many yrs later[4] • HCV infection associated with multiple disease processes[5] – Including liver disease, diabetes, B-cell proliferative disorders, depression, and cognitive disorders • Diminishing HCV infection rates, morbidity through prevention an important ongoing public health initiative 1. Lavanchy D. Liver Int. 2009;29:74-81. 2. Shepard CW, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558-567. 3. IOM. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer. NA Press. 2010. 4. Mitchell AE, et al. Hepatology. 2010;51:729-733. 5. Jacobson IM, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:1017-1029. • • • • • • • • Hepatitis C Virus Infection Population at Risk Transfusion of blood products before 1992 Intravenous drug use Nasal inhalation of cocaine Chronic renal failure on dialysis Incarceration Occupational exposure to blood products Transplantation of an organ/tissue graft from an HCVpositive donor Body piercing and potentially tattoo Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C fact sheet. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/c/fact.htm. Accessed February 1, 2006. Routes of Transmission Injecting drug use 60% Sexual 15% Transfusion 10% (before screening) Occupational 4% Other 1%* Unknown 10% * Nosocomial; iatrogenic; perinatal Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hepatitis C Virus Diagnostic Testing Diagnostic Test Type Specifications Serologic Virologic Mode of detection Antibodies Virus Sensitivity > 95% > 98% Specificity Variable > 98% Detection postexposure 2-6 months 2-6 weeks Use Screening Confirmation HCV Infection - Liver Biopsy • Only test that can accurately assess – Severity of inflammation – Degree of fibrosis • Determines the following – Risk for developing cirrhosis in future – Need for therapy – Need for ongoing therapy when initial treatment has failed Hepatitis C Virus Response to Acute Infection 200 + ALT (IU/l) 150 HCV RNA + Resolution 100 Chronic 50 0 0 6 12 Month Illustration by Mitchell L. Shiffman, MD. 18 24 Prevalence of Anti-HCV, United States, 1999-2002 (NHANES) Overall prevalence: 1.6% (4.1 million) Born ~1945-1965 Prevalence of anti-HCV 8% 7% Men 6% Women 5% 4% 3% 2% 1% Age Group (years) Armstrong et al. AASLD 2004. 55+ 50-54 45-49 40-44 35-39 20-34 6-19 ALL 0% HCV to HCC Pyramid 1% HCC (1%–3%/y) Cirrhosis 15% (10%–30%/y) 25 y Chronic Hepatitis HCV Infection Graphic courtesy of Dr. H.B. El-Serag. 90% (60%–95%/y) 100% Liver Cancer Has the Fastest Growing Death Rate in the United States Trends in US Cancer Mortality Rates All Other Cancers (Average) Corpus & Uterus, NOS Testis Lung & Bronchus (Female) Esophagus Thyroid Liver -2 -1.5 -1 -0.5 0 0.5 Annual Percent Change (1994–2003) 1 1.5 NOS = not otherwise specified. National Cancer Institute. Seer Summary Figures and Tables. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2003/results_merged/topic_graph_trends.pdf. Accessed on October 17, 2008. 2 Chronic Hepatitis C Infection Progression to Cirrhosis Mild 15%-33% Moderate Severe Cirrhosis A 20%-33% Cirrhosis C HCC 0 10 20 30 Years Shiffman ML. Viral Hepatitis Rev. 1999;5:27-43. 40 50 Established Risk Factors for Progression of Fibrosis and Cirrhosis Male gender Longer duration of infection Age >40 years at time of infection Alcohol excess >50 gm/day - men >30 gm/day - women Persistently elevated ALT levels HIV, HBV coinfections Organ transplantation Poynard T, Lancet 1997 349:825-32 Mathurin P, Hepatology 1998 27:868-72 Benhamou J, Hepatology 1999 30:1054-8 Newly-Recognized Risk Factors for HCV Disease Progression Menopausal status Cannabis Insulin resistance Obesity, metabolic syndrome Chronic HCV Infection Normal vs Elevated Serum ALT Portal 26% Bridging 6% No fibrosis 23% Bridging 13% Portal 20% Cirrhosis 18% Cirrhosis 6% Mild 39% Normal ALT Shiffman ML, et al. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1595-1601. No fibrosis 16% Elevated ALT Mild 33% HCV RNA effect on Liver Histology & Fibrosis Serum HCV RNA does not correlate with level of fibrosis Log HCV RNA (copies/mL) 8 Genotype 1 2 3 4 6 4 2 0 No Fibrosis Portal Fibrosis Ferreira-Gonzalez A, et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:9-18. Bridging Cirrhosis Fibrosis HCV and Alcohol 100 Cirrhosis (%) 80 60 HCV HCV + alcohol 40 20 0 10 20 30 40 Years Following Exposure Excessive alcohol intake characterized as > 40 g/day for women and > 60 g/day for men. Wiley TE, et al. Hepatology. 1998:28:805-809. Past and Future (Estimated) US Incidence and Prevalence of HCV Infection Decline among IDUs Overall incidence Infections per 100,000 150 100 50 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 Graphic courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000 2010 2020 2030 The Changing Face of HCV in the US 6,000,000 Ever HCV infected All chronic HCV Acute HCV infection Cirrhosis Peak incidence Persons (n) 5,000,000 Peak cirrhosis 4,000,000 3,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 Yr 2000 2010 2020 2030 Reprinted from Gastroenterology, 138, Davis GL, et al, Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression, 513-521, Copyright 2010, with permission from Elsevier. HCV Life Cycle and DAA Targets Receptor binding and endocytosis Transport and release Fusion and uncoating ER lumen (+) RNA LD LD Translation NS3/4 and protease polyprotein inhibitors processing Membranous web Virion assembly LD ER lumen NS5A* inhibitors *Role in HCV life cycle not well defined Adapted from Manns MP, et al. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:991-1000. NS5BRNA polymerase inhibitors replication Nucleoside/nucleotide Nonnucleoside Sustained virologic response (SVR) as Clinical Endpoint • SVR used as endpoint of successful HCV treatment – Defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA levels 24 wks after end of treatment • Achieving SVR results in significant reduction of HCV-associated complications and mortality[1,2] SVR better No SVR better Genotype 1 P < .0001 Genotype 2 P = .004 Genotype 3 P < .0001 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 All-Cause Mortality HR (95% CI) 1. Morgan TR, et al. Hepatology. 2010;52:833-844. 2. Backus L, et al. 2010 AASLD. Abstract 213. HCV Standard of Care Prior to May 2011 GT1 (most common in US, Europe) least responsive to pegIFN/RBV PegIFN alfa-2b 1.5 µg/kg/wk + RBV 800 mg/day for 48 Wks[1] 100 100 82 SVR (%) 80 60 76 80 60 54 PegIFN alfa-2a 180 µg/wk + Weight-Based RBV (1000 or 1200 mg/day) for 48 Wks[2] 56 46 42 40 40 20 20 0 n = 511 Overall 348 147 GT1 GT2/3 0 n = 453 Overall 298 140 GT1 GT2/3 1. Manns MP, et al. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. 2. Fried MW, et al. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. Suboptimal Virologic Responses HCV RNA (log10 IU/mL) 8 PegIFN/RBV 7 6 Relapse Null response 5 4 Breakthrough 2 log10 decline 3 Partial 2 response Limit of detection 1 Incomplete 0 treatment 0 4 8 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 54 60 66 72 78 Wks McHutchison JG, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580-593. Development of Viral Resistance Drug-susceptible quasispecies Drug-resistant quasispecies Viral Load Treatment begins Selection of resistant quasispecies Incomplete suppression Inadequate potency Inadequate drug levels Inadequate adherence Preexisting resistance Time Limitations of PegIFN/RBV • In GT1/4 slow responders variable results achieved by extending therapy to 72 wks [1-4] • Few options available for patients who fail pegIFN/RBV[5-8] • SVR rates consistently lower among blacks, older patients, individuals with advanced cirrhosis[9,10] 1. Berg T, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1086-1097. 2. Pearlman BL, et al. Hepatology. 2007;46:1688-1694. 3. Sanchez-Tapias JM, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:451-460. 4. Buti M, et al. Hepatology. 2010;52:1201-1207. 5. Poynard T, et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1618-1628. 6. Pearlman BL, et al. AASLD 2009. Abstract 815. 7. Jensen DM, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:528-540. 8. Bacon BR, et al. Hepatology. 2009;49:1838-1846. 9. Jacobson IM, et al. Hepatology. 2007;46:982-990. 10. Huang CF, et al. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:751-759. Adherence to PegIFN/RBV: Essential but Challenging Retrospective analysis of pegIFN alfa-2b/RBV trials (N = 511)[1] 100 SVR (%) 80 63 60 54 53 72 75 40 17 20 n= 0 35 10 24 305 30 50 70 90 Adherence Rate (%) • Only ~ 60% of US patients adhere to HCV therapy[2] • Drug exposure correlates with SVR; ≥ 80% adherence correlates with SVR[1,3] • Patient self-report overestimates adherence[4] • Adherence wanes over time[4] 1. McHutchison JG, et al. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061-1069. 2. Mitra D, et al. Value Health. 2010;13:479-486. 3. Raptopoulou M, et al. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:91-95. 4. Smith SR, et al. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1116-1123. Limitations of IFN-based therapy 2. Tolerability and acceptance 100 HCV RNA+ Patients 40 Eligible Patients 28 Start Therapy 5 Cures Ineligible patients, 60% Eligible patient refusal, 30% Patient dropout or nonresponse, 75% Modeled on Falck-Ytter Y. Annals 2002. IL28B Genotype a Strong Predictor of SVR With PegIFN/RBV in Genotype 1 HCV Whites (n = 871) Blacks (n = 191) Factor Associated With SVR Hispanics (n = 75) Odds Ratio (95% CI) 7.3 6.1 IL28B rs12979860 genotype (CC vs TT) 5.6 4.2 Baseline HCV RNA (< vs ≥ 600,000 IU/mL) 5.1 2.4 3.0 1.1 Baseline fibrosis (METAVIR F0-F2 vs F3-F4) 4.1 0.1 Ge D, et al. Nature. 2009;461:399-401. 1.0 10.0 Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents • Directly target HCV • Improve virological response when combined with pegIFN/RBV • HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors (PI) boceprevir and telaprevir approved by FDA, May 2011[1,2] – Indicated in combination with pegIFN/RBV for treatment of GT1 HCV–infected patients who are untreated or who have failed previous therapy 1. Boceprevir [package insert]. May 2011. 2. Telaprevir [package insert]. May 2011. 3. Key Factors for Considering Treatment Candidacy for PI-Based Therapy Factor Role Genotype Boceprevir and telaprevir licensed only for patients with genotype 1 HCV Fibrosis stage Individuals with mild or moderate fibrosis have better rates of SVR with PI-based triple therapy than those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis SVR rates for individuals with cirrhosis are markedly improved with PI-based therapy vs pegIFN/RBV alone, but SVR rates are still lower than for individuals with F0-F3 fibrosis Treatment experience Treatment-naive patients and previous relapsers or partial responders to IFN-based therapy have excellent response rates with PI-based therapy Both previous partial responders and previous null responders have lower SVR rates with triple therapy than treatment-naive patients or relapsers. Previous null responders have the lowest SVR rates with triple therapy Boceprevir and Telaprevir Clinical Trials • Phase III trials leading to approval – Boceprevir plus pegIFN/RBV • SPRINT-2: treatment-naive patients[1] • RESPOND-2: treatment-experienced patients[2] – Telaprevir plus pegIFN/RBV • ADVANCE: treatment-naive patients[3] • ILLUMINATE: treatment-naive patients[4] • REALIZE: treatment-experienced patients[5] 1. Poordad F, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. 2. Bacon BR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207-1217. 3. Jacobson IM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416. 4. Sherman KE, et al. 2010 AASLD. Abstract LB2. 5. Zeuzem S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417-2428. Telaprevir Monotherapy and Development of Resistance Telaprevir Dosing 8 Patient 1018 6 4 LOD 2 0 Log10 HCV RNA (IU/mL) Log10 HCV RNA (IU/mL) 8 Telaprevir Dosing Patient 1002 6 4 LOD 2 0 1 Days 14 HCV RNA (>100 IU/mL) Wild type T54A V36A/M Kieffer TL, et al. Hepatology. 2007;46:631-639. 1 R155K/T 36/155 A156V/T 36/156 Days 14 Phase III SPRINT-2: Boceprevir + PegIFN/RBV in GT 1 Tx-Naive Patients Randomized, placebo-controlled trial Treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 HCV (2 cohorts: N = 938 nonblack and 159 black) PR* (n = 316, 52) PR* (n = 311, 55) BOC + PR* (n = 316 nonblack, 52 black) RVR† Wk 28 Wk 4 No RVR Follow-up PR* BOC + PR* (n = 311 nonblack, 55 black) PR* (n = 311 nonblack, 52 black) *BOC 800 mg q8h; pegIFN alfa-2b 1.5 µg/kg/wk; weight-based RBV 600-1400 mg/day. †Undetectable HCV RNA at Wk 4 of BOC treatment (ie, at Wk 8) and at all subsequent assays. Poordad F, et al. N Eng J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. Wk 72 Wk 48 Follow-up Follow-up Follow-up SPRINT-2: Response Rates According to Race 4-wk PR → response-guided BOC + PR 4-wk PR → 44-wk BOC + PR Nonblack Patients 100 48-wk PR Black Patients 100 P < .001 80 80 68 P = .004 60 40 40 23 20 0 Patients (%) Patients (%) 67 P = .04 9 n = 211 213 125 SVR 60 53 42 40 23 20 12 8 21 18 37 Relapse Poordad F, et al. N Eng J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. 0 22 29 SVR 12 3 17 14 6 2 Relapse Phase III RESPOND-2: Boceprevir in GT 1 Previous Nonresponders to PegIFN/RBV Wk 36 Wk 8 No RVR RVR Wk 4 Wk 48 Follow-up† PR* (n = 162) Treatmentexperienced patients with GT 1 HCV PR* (n = 161) (N = 403) BOC + PR* (n = 162) BOC + PR* (n = 161) PR* (n = 80) *BOC 800 mg TID; pegIFN alfa-2b 1.5 µg/kg/wk; weight-based RBV 600-1400 mg/day. †Follow-up for 24 wks after completion of therapy. Bacon BR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207-1217. PR* Follow-up† Follow-up† Follow-up† RESPOND-2: SVR Rates With Boceprevir-Based Therapy by Previous Response SVR rates with boceprevir-based triple therapy higher among previous relapsers vs previous partial responders to pegIFN/RBV therapy (previous null responders excluded from study) – Both groups had higher SVR rates vs pegIFN/RBV alone 100 Previous partial response SVR (%) 80 75 69 60 40 52 40 29 20 0 Previous relapse 7 n/N = 23/57 72/105 30/58 77/103 BOC RGT Bacon BR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207-1217. BOC/PR48 2/29 15/51 PR48 Phase III ADVANCE: Telaprevir + PegIFN/RBV in GT 1 Tx-Naive Patients Randomized, placebo-controlled trial Wk 8 TVR + PR* (n = 364) Treatment-naive patients with GT 1 HCV TVR + PR* (n = 363) Wk 24 Wk 12 eRVR†: PR* Wk 72 Wk 48 Follow-up PR* eRVR†: PR* Follow-up Follow-up PR* Follow-up (N = 1088) PR* (n = 361) *TVR 750 mg q8h; pegIFN alfa-2a 180 µg/wk; weight-based RBV 1000-1200 mg/day. †eRVR = undetectable HCV RNA at Wks 4 and 12. Jacobson IM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416. Follow-up ADVANCE: Overall SVR and Relapse Rates 100 P < .0001 for both treatment arms vs control 80 Patients (%) T8PR24/48 (n = 364) T12PR24/48 (n = 363) PR48 (n = 361) 69 75 60 44 40 28 20 0 n= 250 271 158 SVR Jacobson IM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416. n= 9 9 28 27 Relapse 64 REALIZE: Telaprevir in GT1 TreatmentExperienced Patients Randomized 2:2:1; stratified by HCV RNA and previous response Wk 4 Wk 12 Telaprevir 750 mg q8h + PR* (n = 266) Patients with GT1 HCV who previously failed pegIFN/RBV Placebo + PR* (n = 264) Wk 16 Wk 48 Placebo + PR* PR* Telaprevir 750 mg q8h + PR* PR* (N = 632) Placebo + PR* (n = 132) *PegIFN alfa-2a 180 µg/wk + RBV 1000-1200 mg/day. Zeuzem S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417-2428. PR* 24-wk follow-up for SVR REALIZE: SVR Rates With TelaprevirBased Therapy by Previous Response SVR rates with telaprevir-based triple therapy higher among previous relapsers vs previous partial responders vs null responders to pegIFN/RBV – All groups had higher SVR rates vs pegIFN/RBV alone T12/PR48 Previous Relapsers 100 83* LI T12/PR48 Pbo/PR48 Previous Partial Responders Previous Null Responders 88* SVR (%) 80 59* 60 54* 40 29* 24 15 20 n/N= 0 33* 121/145 124/141 16/68 29/49 Zeuzem S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417-2428. 26/48 4/27 5 21/72 25/75 2/37 *P < .001 vs Pbo/PR48 Patients Who Are Not Candidates for PI-Based Therapy • Patients with previous serious adverse events leading to premature pegIFN/RBV treatment discontinuation • Contraindications for boceprevir and telaprevir therapy – Pregnant women or men whose female partners are pregnant – Coadministration with other drugs highly dependent on CYP3A4/5 for clearance and for which elevated plasma concentrations associated with serious/life-threatening events – When coadministered with potent CYP3A4/5 inducers where significantly reduced boceprevir or telaprevir plasma concentrations may be associated with reduced efficacy • Safety and pharmacokinetics of the PIs have not been studied in patients with decompensated cirrhosis or in liver transplant recipients Resistance to Protease Inhibitors • Resistance may develop rapidly with protease inhibitors • It is ESSENTIAL that patients take pegIFN/RBV with protease inhibitors • NEVER dose reduce a protease inhibitor • Always STOP the protease inhibitor if HCV RNA begins to increase Boceprevir Regimens • Treatment-naive patients – 4-wk lead-in period of pegIFN/RBV alone, then triple therapy with BOC 800 mg TID + pegIFN/RBV for 24-32 wks • Duration dependent on treatment response* • Followed by additional 12 wks of pegIFN/RBV alone for slow responders • Previous partial responders and relapsers – 4-wk lead-in period of pegIFN/RBV alone, then triple therapy with BOC 800 mg TID + pegIFN/RBV for 32 weeks • Followed by additional 12 wks of pegIFN/RBV alone for slow responders • Previous null responders and all cirrhotic patients – 4-wk lead-in period of pegIFN/RBV alone, then triple therapy with BOC 800 mg TID + pegIFN/RBV for 44 weeks *Treatment duration covered in detail in next section. Boceprevir [package insert]. 2011. Telaprevir Regimens • Treatment-naive patients and previous relapsers – Triple therapy with TVR 750 mg TID + pegIFN/RBV for 12 wks, followed by 12-36 wks of pegIFN/RBV alone • Duration of pegIFN/RBV dependent on treatment response* (except cirrhotics may benefit from full 48-wk course) • Previous partial and null responders – Triple therapy with TVR 750 mg TID + pegIFN/RBV for 12 wks, followed by 36 wks of pegIFN/RBV alone *Treatment duration covered in detail in next section. Telaprevir [package insert]. 2011. Pros and Cons of Treating vs Deferring Therapy Once PIs Are Available Treat Defer Protease inhibitors substantially increase chance of SVR Current regimens complex, challenging adverse events Successful treatment may arrest progression of liver disease (including potential for cirrhosis, HCC, etc) Potential for better treatment options in future, eg, better response rates, fewer adverse events, shorter duration Many patients already “warehoused” awaiting DAAs, but when is the right time to exit the warehouse? Risk of resistance if therapy fails; impact on future options? Study 110: Preliminary Data in HIV/HCV Coinfection • Higher rates of undetectable HCV RNA at Wks 4 and 12 with telaprevir plus pegIFN/RBV vs pegIFN/RBV alone – Similar results regardless of use of concurrent ART Undetectable HCV RNA, Wk 4 (ITT) Undetectable HCV RNA (%) 100 80 71 75 64 70 60 40 12 20 0 n/N= 0 5/7 12/16 9/14 26/37 Telaprevir + PR 0/6 0 1/8 0/8 PR Sulkowski M, et al. 2011 CROI. Abstract 146LB. 5 1/22 ATV/RTV-based ART Total 100 80 71 75 57 60 Undetectable HCV RNA (%) No ART EFV-based ART Undetectable HCV RNA, Wk 12 (ITT) 68 40 17 20 0 n/N= 5/7 12/16 8/14 25/37 Telaprevir + PR 1/6 12 12 14 1/8 3/22 PR 1/8 Select DAAs in Clinical Development Phase I Phase II Phase III Protease Inhibitors ABT-450 ACH-1625 GS 9451 MK-5172 VX-985 BMS-650032 CTS-1027 Danoprevir GS 9256 IDX320 Vaniprevir BI 201335 Boceprevir Telaprevir TMC435 Nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitors BI 207127 IDX375 ABT-333 ABT-072 ANA598 BMS-791325 Filibuvir Tegobuvir VX-759 VX-222 Nucleoside polymerase inhibitors NS5A inhibitors IDX184 PSI-7977 RG7128 A-831 PPI-461 BMS-790052 BMS-824393 CF102 Points to remember • Incidence is declining, but prevalence of HCVrelated cirrhosis will markedly increase in next 10-20 years • HCV treatment can induce permanent remission and reduces mortality and morbidly • DAAs markedly increases effectiveness of treatment in difficult to treat patients (genotype 1, advanced fibrosis, previously treated and African Americans)