GOT LOCAL? Environment and Society

advertisement

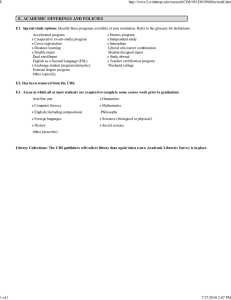

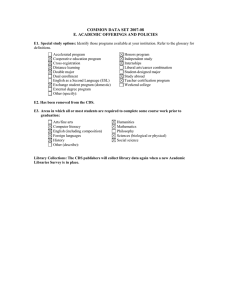

GOT LOCAL? Environment and Society Final Project Group #5: Adriane Dellorco Terence Crane Cambria Hamburg Michael Kenney Environment and Society 101 Professor John Petersen May 4, 2000 Table of Contents: Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………..3 So Why Local? ……………………………………………………………………...3 Background …………………………………………………………………………4 CDS Operations History CDS Requirements for Purchasing Food Where We Are Now ………………………………………………………………..6 CDS Purchasing from OSAP Forming a Farming Co-operative Interviews with Farmers ………………………………………………………… .8 Ron Barkus Joe Solomon Carol and John Fortney Shirlean Smith Future Plans ……………………………………………………………………….12 Suggestions Continued Contact Help Gerry Gross Local Treats in DeCafe Including Local Organic Processed Foods Summary: Concerns, Recommendations ………………………………………..14 Similar Programs …………………………………………………………………16 Hendrix College Local Food Project Bates College Local Foods Purchasing Program Material Cited ……………………………………………………………………..18 Appendix: Primary Sources and Related Information …………………………19 “Where Are Food Comes From: The Oberlin College Food System” Minutes from Administration and Local Foods Meeting, March 17 and 23, 2000 Interviews with Representatives from the Bates College Local Food Program Excerpts from Oberlin and the Biosphere Campus Ecology Report, 1998 Interview with OEFFA Director “CDS, Local Foods, and the Economy,” by Adriane Dellorco Preliminary Report on Lorain County Vegetable and Fruit Growers Articles on Hendrix College and Bates College OSCA Local Foods Information GOT LOCAL? Environment and Society Final Project ABSTRACT The movement to get local foods into Oberlin College’s Campus Dining Service (CDS) has been gathering momentum over the years. Beginning in the Fall semester of 1999 as a group project for the Sustainable Agriculture ExCo, four students began work to research the feasibility of getting local foods into CDS. During the Spring semester, this group has 2 blossomed into a local foods group consisting of ten dedicated members who have been at the forefront of this initiative. This group will be a chartered organization next year with the name Support Local Organic Produce (SLOP). For an Environment and Society (ENVS 101) final project, the four writers of this report (some of them already members of the local foods group) have chosen to become involved. The local foods group on campus has already undertaken the initial process to get local foods into CDS. The primary objective of the writers of this report has been to take the next step and initiate the formation of a local farmers’ co-operative to sell to CDS. Our product is this report documenting the process and our work in realizing this goal. SO WHY LOCAL? Taste. Local food comes directly to us from a much closer source compared to most supermarket food. It is thus picked and eaten at the height of its freshness, resulting in a taste that is unparalleled. Nutrition. Nutritional value declines dramatically as time passes after harvest. Since locally grown food is fresh, it is more nutritionally complete. Also, the local farmers in this area use very little, if any, pesticides and fungicides. Local food is therefore more pure and safer from chemical residue. Regional Economic Health and Food Security. By buying local foods, we keep money in the regional economy, improving the quality of life for our neighbors and ourselves. Supporting local agriculture also increases our regional food security by decreasing our dependence on far-away food sources. Importing from larger food sources tends to promote huge, industrial agribusiness, which has shown to have harmful effects on the land and to be more expensive and less efficient when all the costs, including long term environmental and transportation, are calculated. Transportation costs account for approximately 5 percent of America’s food spending. For CDS, this translates into about $75,000 per year, based on CDS’s annual school year budget of approximately $1.5 million. (Dwyer et al. 28) Energy Conservation. From farm to plate, the average food particle travels 1300 miles (Lovins 68). Buying locally decreases this distance and, consequently, our dependence on petroleum, a non-renewable energy source. One fifth of all the petroleum used in the US is used in agriculture; again, buying locally conserves energy at the distribution level. Preventing Urban Sprawl. For the last fifty years, cities have been expanding into the countryside, eating up farmland and making small-scale farming exceedingly difficult. According to the American Farmland Trust, Lorain County is the seventh most threatened county containing prime agricultural land in the nation due to urban sprawl (Masi 2000). It is wasteful to abandon existing infrastructure only to build on the outskirts where the act disrupts the environment unnecessarily. Buying locally keeps smaller farmers in business, preventing land from being bought up and zoned for commercial development. 3 Passing on the Stewardship Ethic. When buying locally you raise the awareness of yourself and those around you about how food purchasing decisions, and indeed most everyday decisions, can make a difference in the life of you and your community. BACKGROUND CDS Operations The Sodexho Marriott Corporation operates Oberlin College's Campus Dining Services (CDS). CDS maintains five dining facilities: Stevenson, Dascomb, Talcott, Lord Saunders, and Wilder (De Café and Rathskellar). About 70% of the student body is fed through CDS. (Dwyer 27) Oberlin College has contracted outside firms to manage its dining services ever since firms were created to do this in the 1960s. A self-evaluation test is on order by Michele Gross, head of the dining division of Residential Life and Services, to determine if Oberlin College meets the criteria that would make self-operation feasible. This self-evaluation will be done next year, during which the College will be taking bids for other contracts, or creating a self-operation plan based on this evaluation. Michele Gross thinks, “there must be some reason why we have contracted out all these years. I just don’t know exactly what it is. I suspect we will not be self-operated”(Personal interview). Marriott has operated Oberlin’s board program since 1985 (Dwyer 27). As a subsidiary, CDS purchases food through the Sodhexo Marriott Corporation, giving it immense buying power. When food is purchased, it is evenly spread throughout all the dining halls. CDS receives daily deliveries of food. Marriott’s hired dietitian, Joan Boettcer, plans menus six months in advance, but menu plans can be changed two weeks in advance if needed. (M. Gross 17 March 2000) The College pays Marriott a flat fee to manage the dining halls. Marriott manages and pays its employees only. If the College chooses to buy organic, or more expensive products, Oberlin College foots the bill. Marriott is not in a position to affect the bottom line, per se. CDS sets the expectations by telling them the kinds of things they want. (M. Gross 17 March 2000) The College is in the middle of a four-year contract with Marriott that expires in two years (2002). Next year CDS will go through the process of Request for Proposals (RFP) and put together a bidding contract to ask for bids from other firms to manage the college. CDS will ask the students what they want to demand of firms in the RFP, and will work on writing a proposal through the Housing and Dining Committee next January or March. (M. Gross 23 March 2000) The College reevaluates all of its contracts every ten years, ranging from janitorial contracts to CDS contracts. This overhaul reassessment is made more frequently if there is evidence of student dissatisfaction. This ten-year reassessment is coming up in the next year or two, and thus, CDS’ contract with Marriott will be reevaluated. Michele Gross said that in regards to CDS’ contract with Marriott: “We should have gone through a competitive bidding 4 process four years ago, but now we are starting that again. A committee in Housing and Dining will work on it.” (Personal interview) The History Students have tried throughout the years to encourage CDS to buy local organic food, yet these attempts have always resulted in failure. The most recent attempt was made two years ago by Dave Lewis and other students to get CDS to purchase from Oberlin Sustainable Agriculture Project (OSAP). According to Michele Gross, at that time: “David Benzing [biology professor] was giving talks on the advantages of buying locally and supporting the failing economy of Lorain County. There was a lot of interest in discussion with the college after the talks, so I met with David Benzing and Ken Sloane [president of OSAP] to determine the College/Marriott buying rules.” (Personal interview) From these meetings, some progress was made until what seemed like an impossible obstacle was encountered. Benzing created a list of all the produce that was available during what months. It was decided that OSAP could not produce enough for CDS, being that CDS demands such a high volume. It was decided that during freshman orientation, for example, that CDS would buy a bushel of tomatoes or something similar. All negotiations came to a halt, however, when it was discovered that OSAP could not afford to pay for the $5 million liability insurance that the College and Marriott required of all the firms that it purchases from. Michele Gross explains: “We would work with OSAP quantity-wise, through Orr and Benzing, but then OSAP said it couldn’t afford the insurance, so I filed all the information away.” (Personal interview) During this time, Michele Gross and David Jenzen, the Marriott representative to CDS, looked into purchasing from the Federation of Ohio River Co-ops (FORC), a food distributor that provides the Oberlin Students Cooperative Association (OSCA) with the majority of its organic processed foods and some organic produce. According to Michele Gross, she made one call to FORC to ask if they were interested in selling to CDS, but because they did not have the necessary insurance and were not willing to pay for it, FORC declined the offer. (M. Gross 17 March 2000) CDS Requirements for Purchasing Food $3 Million Liability Insurance: Both Marriott and the College require $3 million liability insurance from all the firms that they purchase food from. This means around $2700 to $3000 per producer, according to CDS dietitian Joan Boettcer, whose husband is an insurance agent (Boettcer 2000). This is a decrease from two years ago when the $5 million insurance was required. If a cooperative of farmers was recognized as one entity, they could collectively pay for the insurance, instead of being charged individually. According to Russell Libby, the Executive Director of the Maine Organic Farming and Gardening Association (MOFGA), who was a key figure in establishing the local foods purchasing program at Bates College, Oberlin College has an extremely high insurance requirement that rivals that of international food 5 distribution. The largest supermarket chain in Maine only requires $1 million liability insurance from the firms that it buys from. (Libby 2000) Safety Inspection The farm must pass an annual $150 safety inspection, which is performed by the Ohio State Department of Agriculture. According to Gerry Gross (the head farmer at OSAP), who called the Department of Agriculture to ask about this inspection, if a farm is organically certified, it does not need the inspection. The inspection does not appear to be too stringent. (G. Gross 2000) Official Recognition as a Firm Marriott must set up any firm that it intends to do business with as an official company in their files. Once you are set up as an official company, Marriott can buy from you. This mainly involves paperwork. (M. Gross 17 March 2000) WHERE WE ARE NOW CDS Purchasing from OSAP CDS is going to guarantee to purchase a certain quantity from OSAP in the fall of 2000. They are willing to buy whatever OSAP can offer, with some discretion as to types of produce. OSAP will pay the insurance fee for the coming year. CDS is not expecting daily deliveries from local foods providers. Gerry Gross, head farmer of OSAP, says that he can increase production by 1/3 over last year in order to sell to CDS. OSAP has more equipment this year, and will have summer interns and volunteers from the Sustainable Agriculture ExCo class to provide the labor needed to increase production. Gerry is the only hired help at OSAP during the school year, currently working 40 hours a week already, and upping production without additional help will prove impossible. OSAP would like to sell items that are less labor-intensive, like tomatoes, peppers, members of the brassica family (kale, etc.), beets, Swiss chard, carrots, cabbage, and squash. Gerry Gross and Dave Jenzen have had two meetings to discuss what kinds of food CDS wants, what kinds of foods OSAP can provide, during what months, and for what prices. (G. Gross 17 March 2000) The administration is very supportive of OSAP, and is willing to accommodate them, even if it costs more. The CDS recyclers are currently writing up the job description for next year to hopefully include managing the local foods program in CDS (Stratton 2000). Michele Gross said, “It is worth our while to buy local foods. But in the summer we feed six-year-olds, and they don’t care. However, if we need to buy in the summer to show our support to OSAP, I am willing to look into that. Money isn’t the bottom line when it comes to students” (Personal interview). On May 11, 2000 there will be a meeting with the administration, OSAP, and students to finalize and set up written agreements for OSAP to sell to CDS. 6 Forming a Farming Co-operative The students who are writing this report have been working on forming a cooperative of local farmers to sell to CDS for the Spring of 2001, or earlier, if that can be arranged. We have visited four farmers besides OSAP who are members of the newly formed Vendors Association of the Oberlin Farmers’ Market. These farmers were recommended to us by Ken Sloane, based on their ability to produce large quantities and more off-season produce. These farmers are Ron Barkus, Joe Solomon, John Fortney, and Shirlean Smith. They are all interested in the concept of this endeavor, with varying degrees of skepticism and questions as to how it would actually work out in practice. We hope to make the Vendors Association the umbrella insurance holder to sell to CDS, as it currently is the umbrella insurance holder of its members selling in the Farmers’ Market. We would like to simply expand its capacity as a group insurer to cover the insurance requirement for CDS. This would, however, most probably increase the dues that members must pay to cover the higher insurance the CDS demands. Ken Sloane, president of OSAP and founder of the Vendors Association, intends to work on forming the farming co-operative this summer. There are also other students who are members of the newly formed group, Support Local Organic Produce (SLOP), who will be in Oberlin over the summer and want to participate in this endeavor. The Oberlin Farmers’ Market begins May 13, 2000 and will be held every Saturday. Sloane hopes to network with the growers during the market and during Vendors Association meetings to get the ball rolling. By selling to CDS this Fall, OSAP will act as both a “guinea pig” and model to show how the Local Foods Program in CDS will actually work. If other growers see that this program is actually possible by seeing what OSAP is able to do, it may allay their fears and doubts about getting involved. Any mistakes or difficulties that may occur in the early stages of this program with OSAP in the Fall will hopefully be corrected by the time other growers get involved. 7 INTERVIEWS WITH FARMERS We visited four farmers in the area, and talked to them about selling to CDS. This was one of the most interesting parts of the project. Everyone we talked to was very friendly and receptive to the idea. We toured several of the farms, played with the farmers’ dogs, and got some invitations to come back and volunteer. Ron Barkus 526 Fitchville River Road South, New London OH 44851 (419) 929-2014 Description: Mr. Barkus owns Bill’s Veggies (named after his grandson, in the photo shown) and 44 acres of land on the Vermillion River, though presently cultivates only a small percentage of that. He sells a wide variety of produce and flowers, including a great deal of off-season produce, which he grows in greenhouses. In all, he grows eggplant, cabbage, garlic, onions, cucumbers, lettuce (off-season), sweet basil (off-season), corn, strawberries, potatoes, squash, and pumpkins. Concerns and Interest: Mr. Barkus is very interested in selling to Oberlin College, and said he would be able to produce a large volume of produce. He stated he would be willing to increase his production if he received solid commitment from the college that his produce would be bought. He has a large truck, and said he would be able to help with a rotating group delivery system. Considerations: Though he does not use any pesticides and is in all but name organic, he is not certified. Because he doesn’t have to pay the organic certification fee, he is able to sell his produce for less money. For example, last season he sold his tomatoes to Sarah Kotok for around $20-21. Mr. Barkus said he was willing to sell in the off-season, a definite pro. He carries one million in insurance. 8 Joe Solomon 5150 Avon Belden Road, North Ridgeville, OH 44039 (440) 327-4961 Description: Mr. Solomon cultivates a small part of his 26-acre farm and orchard. He and his wife produce a wide variety of produce including: tomatoes, cabbage, raspberries (including both a June & Fall crop), apples, potatoes, herbs, garlic, shallots, green onions, lettuce, and peppers. He sells 14 varieties of peppers, from hot to sweet. Last season he produced between 500-600 bushels of apples. During the tomato season he was producing around 15 flats of cherry tomatoes everyday. He grows ten varieties of apples. Concerns and Interest: Mr. Solomon stated that he was interested in selling to the college but listed a number of concerns. He stated that he was concerned that if he increased his production of a certain crop in response to the College’s supposed demand, they might not buy it all. He stated that the majority of their land (21of 26 acres) presently lays fallow because it isn’t profitable to cultivate it. He is willing to produce more if he can be assured by the college that he would make a profit. Also related to this concern, Mr. Solomon said that certain crops become abundant simultaneously for all farmers and wondered how the college would distribute this demand equally among the farmers. Mr. Solomon was also surprised by the safety inspection that the college requires, and thought that the college ought to cover that fee. Similarly, he was concerned about the insurance fee and stated that even if the $2700 needed for insurance every year was split up between four or five farmers, it might still be difficult for the farmers to break even. He stated that the Vendor’s Association presently carries $1 million in insurance, and suggested the college subsidize the farmers, paying the remaining $2 million coverage. Mr. Solomon also had a concern about the rotating delivery. He felt that it would be difficult for him to help out for lack of a suitable vehicle. He suggested that delivery be synchronized with the farmers market every Saturday or Tuesday, and that the produce be brought to a central location and then delivered. Considerations: Mr. Solomon stated that he would be able to provide an especially large volume of tomatoes and apples. The strawberries and raspberries are a unique offering, as none of the other farmers we talked to grew berries in large quantities. He and his wife were interested in selling apples to the college in fall of 2000. Their farm is not organic, but he uses integrated pest management. Also, he does not use systemics and uses fungicides only on a very strict as-needed basis. None of his produce is genetically modified. Because he is 9 not organically certified, he is able to sell his produce at a slightly reduced cost. He carries $1 million in product liability insurance. Carol and John Fortney 21370 Quarry Road, Wellington OH 44090 (440) 499-4031 Description: The Fortney’s have a small 5-acre organically certified farm. They don’t farm full-time but do produce a large volume of vegetables. Ms. Fortney also makes sweet confections and egg rolls, which she sells. On their farm they grow tomatoes, sweet corn, string beans, cucumbers, zucchini, spelt, potatoes, and they would be able to grow onions and spinach if they were in demand. Concerns and Interest: The Fortney’s were interested in selling to the college. Ms. Fortney was interested in selling her candies as well as produce. Mr. Fortney stated that his volume would be much less than Ron or Joe. They said they would be able to help with delivery and that he had a serviceable pickup truck. As organic farmers, their product is much more labor intensive, and would cost slightly more. Considerations: Presently these farmers are uninsured, though they are covered by the Vendor’s Association policy. Ms. Fortney stated she may get a policy for her candies and bread. Since they are already certified organic, no safety inspection would be necessary. Relative to other organic farms, their produce is relatively cheap. Last year they sold 8001000 lbs. of potatoes. Mr. and Ms. Fortney more interested in growing qualitatively superior rather than mass-produced vegetables, but they are definitely interested in expanding their market to include the college. 10 Shirlean Smith 12012 Jeffries, Milan OH 44846 (419) 499-4031 Description: Shirlean Smith’s rented land encompasses about 12 acres. She grows cucumbers, pickles, asparagus, rhubarb, berries, tomatoes (Roma, yellow, no-acid, low-acid, cherry, carnival, and other special varieties), peppers (12 kinds), eggplant, beans, and sweet corn. She doesn’t grow any below ground crops. Concerns and Interests: While interested, Ms. Smith thought that the safety inspection would make her participation more difficult. She would have to raise prices to cover the fee. Ms. Smith stated that she would like a better idea of what the college needs to know, and more information on expectations and quantity that she would be expected to supply. She stated that Saturday delivery would be feasible. Ms. Smith is presently looking into purchasing insurance, and would like information from the college on the specifics. 11 Considerations: Shirlean Smith is able to provide a wide variety of above ground crops and stated she didn’t use any chemicals, though she’s not certified. She stated that her peppers and eggplants are rarely a uniform shape, and this could be a problem for cooks. Her produce is cheaper, since it is not organically certified. FUTURE PLANS Suggestions Many of these suggestions stem from a conversation with Russel Libby, Executive Director of MOFGA, Main Organic Farming and Gardening Association. (This organization is similar to Ohio’s OEFFA.) He played a critical role in getting Bates College’s local food program started. The most successful farmers co-ops are those that have been started by farmers who were already acquainted and had worked together before. By beginning to form a critical mass of interested farmers from those that are already members of the Oberlin Farmers Market, we hope to tap into a preexisting cohesion. Additionally, we want to be careful that we are not paternalistically coming in and forming a co-operative for them, the way we think it should be done. Co-operatives must serve the needs of its members, and be run by its members. We only hope to serve as a catalyst for the co-operative-making process to begin and act as the co-operative’s liaisons to the college. We should be sure to tell the farmers that the easier we make this operation on the college, the more responsive the college will be and the larger the market for the farmers will be. This entails having a lot of people involved in selling to CDS. Farmers are proud of their produce and generally dislike having their products mix with other farmers’ products. However, working together as a group will ultimately benefit everyone. For example, a group will reduce the cost of the insurance requirement. Group billing will also be much easier on the college, as will skewed production in order to produce more vegetables in the off season when college is in session. A rotating group delivery will also be important to implement. Continued Contact Perhaps the most important thing to do at this point in the process is to keep the momentum. While we are waiting for the final logistics to work themselves out, it is vital to continue contact with the college and farmers in order to make sure communication and intention is clear. Help Gerry Gross In order to get more local foods into Campus Dining Services we need to increase production, starting with OSAP. Gerry Gross, OSAP’s grower, seeing as he is now a oneman show, could use a lot more help. Some steps have been taken in this direction: Summer Interns. OSAP is hiring summer farm apprentices to work on the farm planting, growing, and running the market. 12 Work-Study. We see work-study farm hand positions at OSAP during the school year as a way to get extra labor at minimum cost to the college and OSAP. Brad Masi is currently working on getting work-study positions at OSAP during the school year. According to Masi, “It is my experience that any work study positions we want, we can get as long as a small amount of funding is available” (Personal interview). OSCA co-op positions. Another possibility that will be explored next semester is making volunteering at OSAP an OSCA co-op credited position. Such a position would have to be passed in individual co-ops. The person working at the farm would receive co-op credit hours, hours that are normally completed working for the co-op. From OSAP’s and the college’s perspective this help would be seen as volunteer. Considering OSCA’s enthusiastic support of OSAP, we think this idea will be popular in the co-ops. Local Treats in DeCafe If local farmers can sell in Stevenson, why not in the DeCafe? Students on CDS Board use their Flex dollars in this small café/convenient store. Since students can’t use their Flex dollars in town, this would be a way of bringing town goods to them. The DeCafe is another potential market for local farmers and local producers of all different types of goods. Though the DeCafe wouldn’t demand the variety of produce that the cafeteria does, foods such as apples, berries, beans, and canned goods are always in demand and would sell well. Carol, wife of John Fortney, a farmer we visited who is interested in selling to CDS, sells baked goods at Kotok’s. She is interested in other markets, and we can vouch for her product (Fortney 2000). Including Local Organic Processed Foods Including local organic processed foods in CDS is also a worthy endeavor. Robert Bronstien from FORC was recently contacted in April to see if FORC would be willing to sell to CDS. He seemed very excited about being a supplier, and wanted more information (Schwartz 2000). Organic processed items that we could purchase include things like pasta, beans, peanut butter, tofu, soymilk, oil, etc. FORC also sells a number of organic produce items. SLOP is in the process of contacting Ohio Farm Direct, a supplier of local meat that provides OSCA with most of its meat, to see if they are also interested in selling to CDS. 13 SUMMARY: CONCERNS, RECOMMENDATIONS 1) -Concern: Buying from only OSAP will create a minimal and unstable variety of produce. -Recommendations: The creation of a farming consortium will ensure greater variety and volume. 2) -Concern: There is currently no guideline for local foods expansion into CDS. -Recommendations: A policy should be adopted for Oberlin College to purchase at least half of its food from Ohio sources within ten years. 3) -Concern: This program needs to be managed. -Recommendations: An overseeing committee should be created in order to ensure communication between the producers, Oberlin College, and Marriott. Also, workstudy positions for students to oversee and run this program should be created. The CDS recyclers should also help manage the local foods program in CDS. 4) -Concern: There is not enough labor at OSAP and other local farms. -Recommendations: Work-study and/or co-op positions for students to work at OSAP and other local farms should be created to ensure that these farms can sustain their increased output. 5) -Concern: Current CDS menus are planned six months in advance. -Recommendations: The CDS dietician/nutritionist should plan menus seasonally featuring local and organic foods rather than before the beginning of the school year. This menu needs to be flexible to deal with unexpected changes in crop yield. 6) -Concern: Ohio has a limited growing season, and the school year runs during the off-season. -Recommendations: Various methods should be implemented including green houses, locally stored produce, in-house (CDS) storage, canning, and freezing (Baring-Gould et al. 42). Farmers should be encouraged to grow produce that can be grown during the off-season. 7) -Concern: Students may be ignorant to the virtues of local organic foods. -Recommendations: There should be a local foods section in the dining halls (especially in Stevenson, since this is where the majority of local foods will be used) that lets people know who the food came from and where they are located, along with information about the virtues of buying local and organic (Baring-Gould et al. 47). 14 8) -Concern: Annual inspections are costly ($150). -Recommendations: The College should reimburse the farmers for the $150 inspection. 9) -Concern: Insurance is extremely costly ($3 million). -Recommendations: Farmers should jointly pay the cost of the insurance through the Vendors’ Association in order to reduce the cost. Also, the College should subsidize the farmers’ insurance costs. 10) -Concern: It is inconvenient for the College to bill farmers separately. -Recommendations: Group billing should be implemented. 11) -Concern: Growers tend to produce similar products. -Recommendations: Frequent roundtable discussions between chefs, the purchaser, the growers, and the nutritionist should be instituted to ensure that growers do not grow too many of the same things. Communication is extremely important. 12) -Concern: There is a danger of purchasing the most produce from growers who yield the largest quantities. -Recommendations: Oberlin College should maintain a policy to buy from as many farmers as possible, spreading out purchasing equally. 13) -Concern: Farmers are unsure of Oberlin College’s commitment to purchase their produce. -Recommendations: The College should guarantee that it would purchase what it asks the farmers to produce for it and possibly establish a contract. 14) -Concern: Rotating delivery may be difficult because the farmers are geographically so spread out. -Recommendations: Delivery should be synchronized with the Tuesday and Saturday Farmers Market. 15) -Concern: Farmers are skeptical about how this program will function. -Recommendations: OSAP should be used as an example when it sells produce to CDS this fall. OSCA should also be used as an example – It has been successful for a number of years buying from local farmers, FORC (The Federation of Ohio River Cooperatives), and Lo Presti’s (a local company). Oberlin College should look into becoming a member of OEFFA to show its support for and commitment to this program. Also, growers should be invited to the Oberlin College campus to witness the large quantities of food utilized in CDS and the huge market available to them. 15 16) -Concern: Organic produce is often more expensive and less user friendly because it is not of a uniform shape, and it might need to be washed more thoroughly. -Recommendations: The College needs to understand that implementation of local organic foods into CDS far outweighs the setbacks of costs. The College should also maintain good communication with the chefs and help them to understand that compromises sometimes need to be made. As a long-time cook at Hendrix College declared, “Oh, you want to fix meals like we used to” (Valen 82). SIMILAR PROGRAMS Hendrix College Local Foods Project Hendrix College, Arkansas, instituted a successful local foods program in 1986, raising their in-state produce use from 6% to 30% of their total intake. They hope to eventually raise this to 50% (Valen 77). As with Oberlin College, this project was begun by students. Several students at Hendrix investigated the origins of the food served in their cafeterias and realized that the vast majority of it had traveled thousands of miles to get there, though there were cattle and vegetable farms within sight of campus. After doing research, these students realized the myriad of positive impacts buying locally would have. However, though the student group had the support of the student body and faculty, there were major administrative obstacles to overcome. The first was that the food service was concerned that more skilled staff would have to be hired to deal with the local produce, as the food service at the time was accustomed to using pre-packaged and uniform produce. They thought the switch would bring down efficiency. A second obstacle was that the local farmers were having difficulty competing with the national agri-business distributors. Initially, the College wasn’t willing to pay more for local produce. The fact that the food service at Hendrix did not have large storage facilities to accommodate the influx of produce at harvesting times was another problem. The cafeteria administration was also concerned about how to deal with the variance in the types of vegetables as different vegetables came into and went out of season. How delivery would work was another concern. Hendrix College and their students were resolute in the face of the so many difficulties. The College hired a project coordinator with the specific goal of advancing a local foods program. This coordinator faced the task of making definite changes in a food service system that had been in place for several years. The coordinator began by enlisting the support of cooks and servers, the ones who really have the power to “make or break the project” (Valen 82). Support of the college community was constantly engaged through publicity regarding progress relating to the local foods effort. Patrons of dining halls were always informed why menus were changing, and all this publicity resulted in a good amount of community pride in the fledging local foods program. The program was jump-started with the College buying available produce at nearby farms. The College identified the suppliers personally and profiled their capabilities and quantities of produce. Hendrix solved the delivery issue by designing a rotating delivery schedule. “All the producers agreed to leave their commodities at one location and a standard weekly delivery schedule is followed” (Valen 85). The project 16 coordinator produced a list of foods to be available each week, which is useful for both the cooks and farmers. The aim of the College was for the project to be environmentally, nutritionally and economically sensitive, and thus made it policy to buy organic whenever possible. The appointed coordinator makes continuing efforts at educating the student body about the foods they are eating, using posters, newsletters, table, tents, charts, and nutritional information on each dish. The food service directors were reluctant to embrace any change in methodology, but ultimately were pleased with the positive public attention the local foods programs brought. Bates College Local Foods Purchasing Program A campus environmental issues committee, who wanted to use more organic produce in their dining halls and create a closed loop of food intake and waste output, initiated an institutionalized local foods program at Bates College in Maine. The effort at Bates was inspired and informed in part by the Hendrix College program. However, the Bates program has proceeded in markedly different ways. At Bates, their first priority was organic produce, and it happened that the most inexpensive sources of organic food were local. The group decided that the local produce would be best provided by a loose cooperative of nearby certified-organic growers. An executive chef was hired by the dining service that had dual experience, both at a culinary institute and in extensive gardening projects. This chef, Bradford Slye was instrumental in the implementation of the program. After only four months of discussion local organic produce was used in the campus food service. Delivery was handled rotationally between the six farmers, once a week. The cooperative of farmers tells the chef what is available a week ahead of time. Shipments were rarely turned down, although there were exceptional cases when farmers spontaneously arrived with surpluses of produce that the food service couldn’t use or store. During later years of the program a canning program was set up to provide for some staple items such as tomato sauce. They have found that the farmers are getting a better sense of the quantities and types of produce the college can use. They began with smaller shipments and worked up. Invoices were billed to the cooperative, which made it easier on the College. The food service found in general that the local produce was qualitatively superior, since it had not been “waxed, gassed, preserved, packed, shipped hundreds of miles, sized out, repacked, and otherwise jostled along its journey” (90). However, this came with a tradeoff, for the local produce was often not uniform in size or shape, which was disconcerting for patrons. However, Bates executive chef Slye took this in stride and suggested a shift of perspective towards the food, “I guess you have to like the food as it is, not expect everything to be the size and shape of a golf ball,” (91). Also, unusual shapes and sizes allowed chefs to display their creative talents. The organic produce meant price increases, which the students resisted, but Bates was ready to try alternate dining systems, such as those practiced by Dartmouth and Tufts. Those institutions have replaced their “all-you-can-eat” meal plans for a la carte services. Slye also says that with time they are finding that the cooperative may soon be able to match market prices as the program runs more smoothly. The Bates program could not have happened without consistently institutionalized support from the College, and the commitment of students and administration. 17 Material Cited Baring-Gould L., D. Elshoff, G. Kehm, K. Rae, and K. Schneider. “Where Our Food Comes From: The Oberlin College Food System”. 1988. Boettcer, J. Personal interview. 17 March 2000. Dwyer, M., A. Mack, B. Masi, D. Orr, N. Palmer, K. Warren, and C. Wolfe. “Oberlin and the Biosphere: Campus Ecology Report 1998”. 1998. Fortney, C. and J. Personal interview. 24 April 2000. Gross, G. Personal interview. 17 March 2000. Gross, M. Personal interview. 17 March 2000. Gross, M. Personal interview. 23 March 2000. Keniry, Julian. Ecodemia: Campus environmental stewardship at the turn of the 21st century: lessons in smart management from administrators, staff, and students. Washington, D.C. : National Wildlife Federation, 1995. Pgs 86-98. Libby, R. Telephone interview. 11 April 2000. Lovins, A.L., and Marty Bender. “Energy and Agriculture”. Page 68 in Meeting the Expectation of the Land, Jackson, Berry, Coleman, eds. 1984. Masi, B. Personal interview. 3 March 2000. Schwartz, H. Email interview. 26 April 2000. Stratton, C. Personal interview. 23 March 2000. Valen, Gary L. “Hendrix College Local Food Project.” New Directions for Higher Education, no 77, Spring 1992, pages 77-87. 18 Appendix: Primary Sources and Related Information 19