TEACHERS’ PERSPECTIVES ON HOMEWORK Running Head: The American University in Cairo

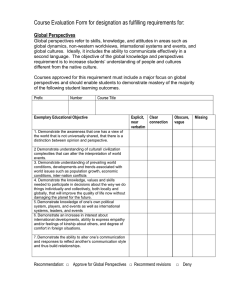

advertisement