CHAPTER 1 Introduction 1.1 Computer Technology

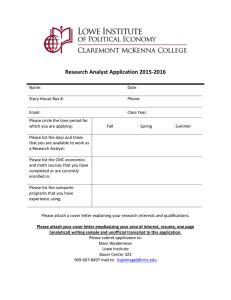

advertisement