The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences

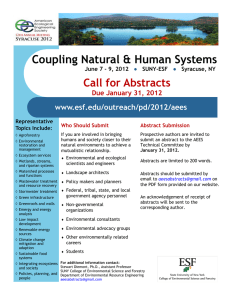

advertisement