He who knows only his own side of the case... Instructor: Dr. Gary Johnson

advertisement

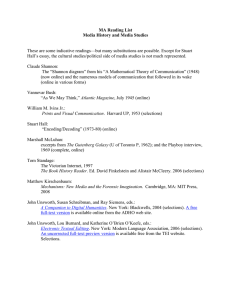

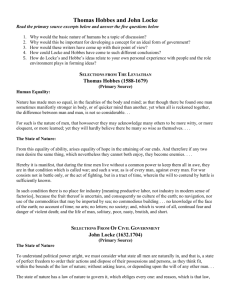

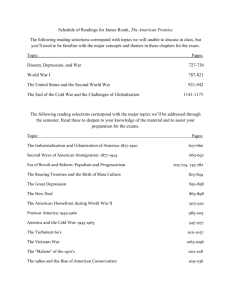

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. John Stuart Mill POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY II Political Science 352 (4 credits) Lake Superior State University Spring, 2003 Instructor: Telephone: Dr. Gary Johnson Office: 635-2763 Home: 635-9415 Office: Hours: Class: Library 221 MTWR 11-12, W 1-2, and by appt TR, 3:00-4:40; Crawford 109 Course Objectives Political Science 352 is an overview of Western political philosophy from the seventeenth century to the twentieth century. The most obvious goal of the course is to familiarize you with the principal ideas of the principal political philosophers of the period. This is our most obvious goal, but it is not necessarily the most important goal. Since few of you, if any, will become historians of political philosophy, our most important objectives in this course lie elsewhere. The ideas of the great political philosophers will actually be our tools for exploring a broad range of important issues that are as relevant today as they were in the seventeenth century. In forcing you to struggle with these issues—and to learn about the answers provided by the great political philosophers of the period—the course has five additional objectives. First, the course should significantly sharpen your analytical abilities. Your efforts to understand the ideas of the great minds of the period should enhance your ability to analyze complex issues in an intellectually sophisticated way. Second, and relatedly, the course should sharpen your critical thinking skills. Third, since you will be exposed to divergent perspectives—and in many cases forced to defend those perspectives—the course should broaden your intellectual perspective. Fourth, because you will do a considerable amount of writing in this course, your writing skills should improve. Fifth, and finally, since you will be required to speak regularly in class, this course should help improve your oral communications skills. Readings The required texts for the course are John Locke, The Second Treatise of Government (Bobbs-Merrill); Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract and Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (Pocket Books); Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto. All are or will be available at the university bookstore. All other required readings will be on reserve in the library or will be handed out in class. Examinations There will be three two-hour exams for the course. The exams will be predominantly essay, and must be written in blue books and with pen. The final exam will not be comprehensive, but you will nevertheless have to make comparisons with material covered earlier. Preview questions will be handed out prior to the exams—there will be no surprise questions. When spelling or writing are unacceptable, you will be required to make corrections before full credit is granted. Participation We will typically use a dialectical method in class. You should therefore be prepared for every class to explain our theorist’s position, to criticize or defend it (as called upon), and to discuss important issues related to the reading. You will receive a participation grade for each class. On a few days we may have a debate or other special activity that will require extra participation. On these days you will receive double or triple participation scores. Your lowest two daily participation grades will be dropped before the average is calculated. Unexcused absences from class will earn a “0” for daily participation (I will assume your absence is unexcused unless you speak to me before or immediately after the class or classes you miss). On days when you are present, but I am unable to assign you a participation grade (e.g., on Participation (cont.) the day of a lecture), your presence will be recorded, but no numerical grade will be assigned. Only the numerical grades will be used in calculating your overall grade. Please note that the most important criterion in assigning participation grades will be quality, not quantity. Journal In place of a paper, you will keep a class-by-class philosophical journal. You will have one entry for every regular class meeting after the first class. In your journal you will record your thoughts about the assigned question(s) for that day, as well as your reflections on issues from the readings or class. Each entry should include your name, the issue number, and the issue (see below). It would be best to prepare your journal entries on a computer, but typewritten or neat handwritten entries are acceptable. Your entries should be maintained in a hard-sided notebook like the one I show you in class. You should normally read the day’s assignment before recording your entry. This will help you understand the intent and significance of the question. Your journal will be graded on the basis of your insight and understanding of the issues, originality and creativity, organization, and quality of explanation. I expect to collect and grade your journal once during the semester, as well as at the end of the semester. These collections will be random and unannounced. You will also be asked occasionally to read your journal entry in class. Such readings will affect your participation grade for that class. Spelling errors and other writing problems will be marked when possible for your benefit, but you should not let a concern about writing make you timid or hesitant. Your journal is a philosophical diary in which you record your struggles and musings on an issue of importance. This is therefore a piece of informal writing about which you do not need to be self-conscious. Class Preparation In reading and preparing for class, you should ask yourself seven questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. What is (are) the principal issue(s)? What is our theorist’s position on the issue? What is right about our theorist’s position? What is wrong about our theorist’s position? What alternative would you propose to this position? What objections may be anticipated to your alternative? What answers would you provide to those objections? Grades The three exams, the journal, and class participation will each be worth 100 points, for a total of 500 points for the semester. The grading scale for all class components, as well as your final average, will be as follows: A, 90-100; B, 80-89; C, 70-79; D, 60-69; F, 0-59. Course Outline 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Thomas Hobbes John Locke Jean Jacques Rousseau Adam Smith The U.S. Founding Fathers David Hume Modern Conservatism Edmund Burke Modern Liberalism Jeremy Bentham John Stuart Mill 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Hegel Communism Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Non-Marxian Socialism Anarchism Michael Bakunin Peter Kropotkin Friedrich Nietzsche A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices. William James Political Philosophy II PS 352; Spring, 2003 Assignments and Exams Date Topic Assignment 1/14 Organization First class. No assignment. 1/16 Hobbes Leviathan. Selections in William Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, Fourth Edition, 362-378. Issue 1: Are humans by nature selfish creatures? If so, how much? How do you know? 1/21 Hobbes Leviathan. Selections in William Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, Fourth Edition, 378-389. Issue 2: Is it possible for an act to be “wrong” if it is not defined as such by a recognized authority? If so, how? What can make something “wrong” if no authority (human or divine) has declared it wrong? How do you know this? 1/23 Hobbes Leviathan. Reread selections in William Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, Fourth Edition, 372-389. Issue 3: From what or whom do you get your conscience? If your obligations as a citizen are in conflict with your conscience, what should you do? Why? 1/28 Locke The Second Treatise of Government, Intro, vii-xxii; Chaps. 1-5, pp. 3-30. Issue 5: Locke says there exists a right to private property. Is his justification of this right adequate? Why or why not? Is there such a right? 1/30 Locke The Second Treatise of Government, Chaps. 7-12, pp. 44-84. Issue 6: What is the origin of government? Take Locke’s answer into account, explaining why you agree or disagree. 2/04 Locke The Second Treatise of Government, Chaps. 13-15, 19, pp. 84-99, 119-139. Issue 7: Do citizens possess an inherent right to revolt? If so, why, and would such a right not threaten social stability? If not, why not, and is this denial a guarantee of oppression? 2/06 Rousseau The Social Contract, Intro (vii-xxiv), Book I (5-26); Book II, Chapters 1-4 (2736). Issue 8: What is freedom? How is freedom achieved? 2/11 Rousseau The Social Contract, Book II, Chapters 5-10 (36-54); Book III, Chapters 1 & 15 (59-64, 98-101); Book IV, Chapters 1-2 (109-114); Chapters 7-9 (134-147). Issue 9: Is there such a thing as the “general will”? If there is, explain what it is and how one can know it. If there isn’t, what criteria should be employed in formulating legislation? 2/13 Exam 1 Prepare for exam using preview sheet. No journal entry. 2/18 Adam Smith Robert Heilbroner, The Worldly Philosophers, Chap. 3, “The Wonderful World of Adam Smith.” Issue 10: Specifically with regard to the economy, is that government best that governs least? Date Topic Assignment 2/20 Hume Mulford Sibley, Political Ideas and Ideologies, Chap. 23, 413-418; David Hume, “Of the Origin of Justice and Property,” in David Hume’s Political Essays (Bobbs-Merrill), 28-38. Issue 11: Why does the concept of justice exist? 2/25 Hume Mulford Sibley, Chap. 23, 418-425. David Hume, “Of the Original Contract,” in David Hume’s Political Essays, 46-61. Issue 12: Why does government exist? 2/27 Madison/Hamilton Richard Hofstadter, The American Political Tradition, Chap. 1; The Federalist Papers, #’s 15, 10, 51. Selections in Alpheus Thomas Mason, Free Government in the Making, Third Edition, 287-289, 293-297, 305-308. Issue 13: If Madison’s analysis of human nature and the origin of government is correct, how could an ideal government be established, if at all? 3/4,6 Spring Break Have a good time!! Come back safely. 3/11 Burke Reflections on the Revolution in France. Selections in William Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, Fourth Edition, 473-493. Issue 14: How important should tradition be in evaluating public policy? 3/13 Burke Reflections on the Revolution in France. Selections in William Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, Fourth Edition, 493-504. Issue 15: Burke criticizes the notion of abstract rights. Are there any such abstract rights—human rights, for example? Why or why not? 3/18 Bentham An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Selections in William Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, Fourth Edition, 505-531. Read editor’s intro carefully. 515-519—read #’s 1-14 carefully, ignore footnotes. 519522—read quickly, but look to understand the “principle of asceticism” and the “principle of sympathy and antipathy.” 522-526—read #’s 10-16 and footnote 6 (523-525) carefully. 526-531—read very quickly. Issue 16: Is the criterion of public utility an adequate guide in the formulation of public policy? Why or why not? 3/20 J. S. Mill On Liberty. Selections in Carl Cohen, Communism, Fascism, and Democracy, Second Edition, 450-467. Issue 17: What limits, if any, should society place on freedom of expression? Why? 3/25 Second Exam Prepare for exam using preview sheet. No journal entry. 3/27 No class Arrowhead Model United Nations will be taking place on campus. Several of us will be involved. No class. No assignment. No journal entry. 4/01 Hegel Mulford Sibley, Political Ideas and Ideologies, Chap. 24, pp. 435-461. Read 435452 carefully, 452-455 quickly, 456-461 moderately carefully. Issue 18: Is it possible to reconcile duty and freedom, or are they naturally always in tension? Why? Date Topic Assignment 4/03 Marx James L. Wiser, Political Philosophy, Chap. 16, 351-358; Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto, 8-31, 43-44. Issue 19: Is the government of a capitalist society merely a tool by which the dominant class protects its interests? Why or why not? 4/08 Marx James L. Wiser, Political Philosophy, Chap. 16, 358-377. Issue 20: Do capitalist employers exploit their employees by, in effect, stealing value that the employees have created through their own labor? Why or why not? 4/10 Utopian Socialism Robert Owen, The Book of the New Moral World. Selections in Carl Cohen, Communism, Fascism, and Democracy, Second Edition, 22-32. Issue 21: Can human character be fundamentally transformed through education? Why or why not? 4/15 Democratic Socialism Clement R. Attlee, The Labour Party in Perspective. Selections in William Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, Fourth Edition, 780-798. Issue 22: Would public ownership of all large-scale industries and enterprises, farmland, and natural resources make the United States a more democratic and just society, assuming that employee pay, promotion, and other rewards were based on merit? 4/17 Anarchism Michael Bakunin, God and the State. Selections in Arthur Lehning, Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, 111-135. Issue 23: Is the idea of God a force for domination, inequality, and injustice? Why or why not? 4/22 Anarchism Peter Kropotkin, “Law and Authority.” in Emile Capouya and Keitha Tompkins, The Essential Kropotkin, 27-43. Issue 24: Kropotkin says that rather than respecting the law, we should “despise law and all its attributes.” Being careful not to set up a straw man, evaluate this proposition. Is Kropotkin right or wrong, or in what senses is he right and in what senses wrong? 4/24 Nietzsche Werner J. Dannhauser, “Friedrich Nietzsche,” in Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey, History of Political Philosophy, Second Edition, 782-803; Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil. Selections in Carl Cohen, Communism, Fascism, and Democracy, Second Edition, 308-313. Issue 25: Is all of life a will to power? If it is, how did it get this way? If it is not, what is the driving force of human activity, and why? 4/29 Final Exam, 5:30-7:30 Use preview sheet to prepare. Issue 26: Reflecting back on your experience over the year (or semester), what are the most important lessons you have learned in this sequence (or course)? Do not evaluate the instructor or course—you will do that on the student evaluation form. Instead, evaluate your own experience and what you have gained from it.