Laokoon Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781), the Enlightenment writer and at the... of author of tragedies, comedies, fables and poems, Lessing was also...

advertisement

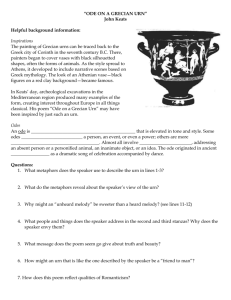

Lessing’s Theories in his Laokoon Debated by John Keats in “Ode on a Grecian Urn” Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781), the Enlightenment writer and at the same time, the conqueror of rational classicism, is the driving force of the literary profession of his time. Not only an author of tragedies, comedies, fables and poems, Lessing was also a literary theorist and critic, a true scholar of literature, an art historian, and a deep philosophical and theological thinker. Born in Goerlitz, an intellectual center in Saxony where his father was an influential Lutheran minister, Lessing began his studies of theology at Meissen and Leipzig, but he renounced this career to become a journalist, librarian, and translator of texts in French, Italian, and Spanish. His deep interest in the art and literature of Ancient Greece and Rome places him in the ranks of the foremost scholars of his age. Friedrich Schlegel (1772-1829) observes in his Kritische Schriften that when Lessing began to write, German literature is one of the youngest among the European literatures (“die deutsche Literatur ist eine der juengsten unter den Europaeischen .”) German literature had not yet developed into the Weimar Classicism of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) and Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805). It remained for Lessing to lead the way to awaken the German mind and to instill in it a philosophy that embodied both the romantic and the classical in the realm of literature. Lessing laid the foundation for a genuine German literature by challenging the literary dicta of Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700-1766) whose views dominated German literature when Lessing came on the scene. For more than a generation, Gottsched and his followers had demanded that German literature adhere to imitating French classical literature with its strict rules drawn from the literary tenets of classical antiquity. This adherence would have excluded works of Shakespeare, Ariosto, Tasso, and Milton from being considered as worthy literary creations! In every aspect of his being, Lessing was German and immersed himself in classical lore without looking at it through foreign interpretations such as those of the French. Unfortunately, Lessing’s works today are little known outside Germany. However, three dramatic works that still generate a broad interest are the comedy Minna von Barnhelm 1 (1766), the tragedy Emilia Galotti (1772), and the philosophical drama Nathan der Weise (1779). Especially important today among scholars everywhere is his critical treatise entitled Laokoon (1766). That Laokoon: Oder, ueber die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie (1766) astonishes the reader with the depth of Lessing’s knowledge of the aesthetics of Ancient Greek and Roman literature and art lends credence to his being awarded the title of “Polyhistor”by an admiring German public. Lessing had great respect for Johann Joachim Winkelmann (1717-1768), the art historian and archeologist whose Hellenic interests reflect his articulation of the differences between Greek, Greco-Roman, and Roman art. He asserted in Gedanken ueber die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke, in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst that the principal characteristics of Greek sculpture exhibited “eine edle Einfalt und eine stille Groesse” (a noble simplicity and a quiet greatness). In his study of the Laocoon statue Winkelmann concluded that natural beauty was the foundation of Greek art. His “noble simplicity and quiet greatness” meant that the sculptor hoped to show that greatness of soul would overcome expression of pain. Lessing, whose knowledge of Laocoon came from his literary study of Homer and Sophocles, maintained that greatness of soul did not require a suppression of an expression of pain. Winkelmann had written in Geschichte der Kunst des Altertumes in the chapter entitled “Von der Kunst der Zeichnung unter den Griechen und von der Schoenheit:” In the anguish and suffering of the Laocoon (statue), which is shown in every muscle and nerve, we see the tried spirit of a great man, who wrestles with torment and seeks to suppress and confine within itself the outbreak of sensibility. He does not burst forth in a loud cry as Virgil describes him to us, but only sad and still sighs come from him….(98) Laocoon, a Trojan hero, was the son of Agenor of Troy and a priest of Apollo or of Poseidon, depending on the sources one reads. He warns the Trojans against the wooden horse that the Greeks left before the walls of Troy. Virgil (70-19 BC) writes in Book II of his Aeneid: “Equo ne credite/Quidquid id est,/timeo Danaos et dona ferentes.” (Do not trust the horse, Trojans. Whatever it is, I fear Greeks 2 bearing gifts.) Various reasons for Laocoon’s death are given in ancient texts, but Virgil’s account is one of the most widely accepted. As Laocoon was sacrificing a bull to Poseidon to gain his favor for the Trojans, Athena, a supporter of the Greeks, punishes him for warning the Trojans about the horse by sending serpents from the sea to kill him and his two young sons. The sublime story of Laocoon’s death was a subject for both poets and artists in the ancient world. Virgil’s rendition in Book II of the Aeneid, lines 199-227 is the poetic version known to most people. According to Pliny the Elder (23-79), the Laocoon sculptural group by the Rhodian artist, Agesander (1st century BC) adorned the palace of the Roman Emperor Titus (39-81). Unearthed in 1506 during the papacy of Julius II on the Equiline Hill in Rome, the Laocoon group can be seen today in the Vatican Museum (see fig. 1). Winkelmann’s comparison of the Laocoon sculptural grouping of Agesander with the poetic description of Virgil stimulated Lessing to write his 1766 critical treatise. The effect of his Laokoon, especially in Germany but also on the rest of the Continent and in England, ushered in a new approach in aesthetic culture and literature. Lessing seeks to resolve Winkelmann’s criticism of Virgil for having Laocoon scream while Agesander suppresses his emotion to a sigh. Lessing concludes: Wenn es wahr ist, daB das Schreien bei Empfindung koerperlichen Schmerzes, besonders nach der alten grieschischen Denkungsart, gar wohl mit einer grossen Seele bestehen kann; so kann der Ausdruck einer solchen Seele die Ursache nicht sein, warum demohngeachtet der Kuenstler in seinem Marmor nicht nachahment wollen, sondern es muB einen andern Grund haben, warum er hier von seinem Nebenbuhler, dem Dichter, abgehet, der dieses Geschrei mit bestem Vorsatze ausdrueket. If it be true that the cry which arises from the sensation of bodily suffering, especially according to the old Greek fashion of thinking, may well consist with a great soul, then the outward expression of such a soul cannot be the cause why- notwithstanding it- the artist should not imitate in his marble this cry; but there must be another cause why, in this respect. 3 He differs from his rival Poet, who has very good reasons for expressing this cry. Lessing presents in his critical essay the differences between the plastic arts and the literary arts. In the plastic arts, such as sculpture and painting, one’s aesthetic response is simultaneous and static, a fact that requires the artist to capture the most pregnant moment in his creation. Agesander does exactly this in the Laocoon group where he has Laocoon opening his mouth ever so slightly which reveals the moment of his realization that he and his sons are doomed to die from the attack of the serpents sent by Athena. By contrast, the literary arts- lyric, epic, and dramatic – affect the reader or listener quite differently. Literature, according to Lessing, is successive and dynamic. In Virgil’s description of Laocoon’s death the poet presents a succession of events that moves toward a climax. This evokes in a person a much different aesthetic response from that of the plastic arts. Lessing takes issue with Winkelmann and makes clear the distinction between Agesander and Virgil’s interpretations of the myth. Laokoon erhebt kein schreckliches Geschrei, wie Virgil von seinem Laokoon singet; die Oeffnung des Mundes gestattet es nicht; es ist vielmehr ein aengstisches und beklemmtes Seufzen, wie es Sadolet beschreibt. Der Schmerz des Koerpers und die GroeBe der Seele sind durch den ganzen Bau der Figur mit gleicher Staerke ausgeteilet, und gleichsam abgewogen. Laokoon leidet, aber er leidet wie des Sophokles Philoket: sein Elend gehet uns bis an die Seele; aber wir wuenschten, wie dieser groBe Mann, das Elend ertragen zu koennen. Laocoon raises no horrible scream as Virgil sings of his Laocoon; the opening of the mouth does not permit it; it is more an anxious and oppressed sigh, just as Jacapo Sadoleto describes it. The pain of the body and the greatness of the soul are spread out through all parts of the statue with the same force and at the same time in various 4 directions. Laocoon suffers, but he suffers like the Philoket of Sophocles: his misery goes to the very depth of our souls; but we wished, like this great man, to be able to bear the misery. With his Laokoon, Lessing sets aside the aesthetic criteria of the Renaissance and Baroque and paves the way for new aesthetic approaches, ranging from neo-Classical purism to neo-Romantic eclecticism. For John Keats (1795-1821) and Leigh Hunt (1784-1859), Lessing’s critical treatise served as an inspiration to these English romantics to contemplate his critical premise regarding the distinction between the plastic arts as simultaneous and static and the literary arts as successive and dynamic. Hunt, as editor of various literary journals, is largely responsible for the publication of much of Keats’ poetry. Keats was fascinated by classical antiquity, and although his financial situation precluded his traveling to Greece and Italy, he took full advantage of the classical treasures, such as the Elgin Marbles, that were a growing part of the British Museum’s collection in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. He also knew well the epic poems of Homer and was especially moved by his description of Achilles’ shield in Book 18 of the Iliad that is considered the beginning of the ekphrastic tradition. This passage implicitly compares visual and verbal means of description most dramatically by weaving elements that could not be part of the shield (like movement and sound) with things that could be (like physical material and visual details).This emphasizes the possibilities of the verbal and the limitations of the visual. What is described becomes real in the reader’s imagination despite the fact it could not exist. Perhaps one of the most important examples of ekphrastic poetry is Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” written in 1819 and published in 1820 in the Annals of the Fine Arts (see fig. 2). Keats, like Homer, mixed descriptions of things that could have been both visible and not visible on the urn, but he differed from Homer in that he made his personal experience in viewing the urn part of his ode. This represents a shift in emphasis that led to a transformation in the genre of ekphrasis. In using the elements of Hellenic ekphrasis, he embraced the past while still concerning himself with the present where his imagination 5 could overshadow reality. Ancient Greece symbolized for Keats a magical, idealized world in his head, accessible only through ancient writings and monumental artwork created by the Greeks during that period. Much speculation has arisen since the publication of this ode regarding what particular vase or urn inspired the poet. At one time it was believed that the “Townley Vase,” part of the collection of Charles Townley (1737-1805) in the British Museum, was the urn from Keats’ ode (see fig. 3). It is wellknown that this large Roman vase in marble from the second century was one of the poet’s favorite artifacts in the museum. Though the subject of “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is neither Roman nor a vase, we know that Keats made a sketch of the marble Greek “Sosibios Vase” in the Louvre that he found in Henry Moses’ book, A Collection of Antique Vases (see fig. 4). Other possible inspirations for the urn are the Roman cameo-glass vessel from the first century that was acquired by the dowager Duchess of Portland in 1774 and later became part of the collection of the British Museum (see fig. 5) and the marble Greek “Borghese Vase” from the first century BC in the Louvre (see fig. 6). Keats’ friend, Leigh Hunt, spoke of the urn as a “sculptured vase,” intimating it was marble and not an Attic red and black vase in clay. Keats’ reference to the “little deserted town” on the day of the wedding has caused some critics to suggest he might have been inspired by pastoral scenes in paintings (see figs. 7 and 8) by Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665). That no specific work of art has been established as the poet’s inspiration for the urn with the wedding procession depicted around its surface, one can assume that his subject for the ode has arisen out of the poet’s imagination, drawn from his personal experiences with both the plastic and literary arts. Scholars since the publication of “Ode on a Grecian Urn” have presented countless analyses of this most famous of John Keats’ poems. The following analysis seeks only to examine the poem as the poet’s personal debate on Lessing’s theory as to which of the two arts, the plastic or the literary, is superior. 6 As we read the memorable first line of the ode- “Thou still unravished bride of quietness” – we are reminded of Lessing’s belief that the plastic artist must not create the most emotional moment but the most pregnant one. The bride is full only of anticipation for the approaching sexual union with her true love. The debate commences when Keats poses the question whether or not the urn’s artist can express the situation “more sweetly” than his poem. The pastoral scenes of Arcady on the urn leave us with the desire to know exactly “what men or gods are these” and details about their specific activities during the day. With this question, Keats implies the simultaneous and static limitations of the plastic arts. The debate continues with the proposition that “Heard melodies are sweet (poetry), but those unheard are sweeter “ (painting/sculpture). The static nature of the plastic arts will allow the young lovers always to remain young and beautiful, and they will experience eternal Spring, but they will be frozen in time on the urn and never reach their goal of living a life together. The limitations of the plastic arts continue to be stressed by the poet. We will never know to what altar the priest is going to sacrifice the heifer for the celebration, nor will we know anything of the people portrayed on the urn whose town will be deserted because they cannot return home. The literary arts, on the other hand, being successive and dynamic, have the potential of conveying a moving succession of events that reveals to us a comprehensive presentation able to provide for us past, present, and future details germane to the subject. In the final stanza Keats addresses directly the “Attic shape” with its “marble men and maidens overwrought.” We are beguiled by the “silent form” which the poet calls a “Cold Pastoral.” We are reminded of the transitory nature of human existence and the permanence of art- “ars longa, vita brevae” with the poet’s conclusion that the urn will continue to exert an aesthetic effect on future generations, long after his generation has passed from the scene into eternity. The intended meaning of the final lines of the ode has intrigued scholars for nearly two centuries: 7 When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st “Beauty is truth. Truth beauty,” – that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. In Book X of The Republic, Plato in his example of the “Bed” presents the concept of the realm of the ideal of which reality is an imitation and art an imitation of that reality. Leaving aside his argument that artists take us one more degree away from the ideal, we can use his concept of art imitating reality to consider art as mimetic. Mimesis is the representation of reality in a form foreign to or different from that reality being represented. In my view Keats’ “beauty” represents all art, both plastic and literary, and his “truth” represents the reality that all artists imitate in their creations. I would venture to say that all forms of art, both plastic and literary, are equal in importance, because they are representations of the real human condition and transcend the ravages of time. Simply put, Keats’ urn is telling us that “art is long and life is short.” 8 Appendix Figure 1: Laocoon Group in the Vatican Museum Figure 2: “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats Ode on a Grecian Urn THOU still unravish'd bride of quietness, Thou foster-child of Silence and slow Time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both, In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy? Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare; 9 Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss, Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve; She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair! Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu; And, happy melodist, unwearièd, For ever piping songs for ever new; More happy love! more happy, happy love! For ever warm and still to be enjoy'd, For ever panting, and for ever young; All breathing human passion far above, That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy'd, A burning forehead, and a parching tongue. Who are these coming to the sacrifice? To what green altar, O mysterious priest, Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies, And all her silken flanks with garlands drest? What little town by river or sea-shore, Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel, Is emptied of its folk, this pious morn? And, little town, thy streets for evermore Will silent be; and not a soul, to tell Why thou art desolate, can e'er return. O Attic shape! fair attitude! with brede Of marble men and maidens overwrought, With forest branches and the trodden weed; Thou, silent form! dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral! When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st, 'Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.' 10 Figure 3: The “Townley Vase” in the British Museum Figure 4: The “Sosibios Vase” in the Louvre 11 Figure 5: The “Portland Vase” in the British Museum Figure 6: The “Borghese Vase” in the Louvre 12 Figure 7: Pastoral Scene by Claude Lorrain Figure 8: Pastoral Painting by Nicolas Poussin 13 Works Cited Keats, John. “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The Oxford Book of English Verse: 1250-1900. Ed. Arthur Quiller Couch. New York: Oxford University Press, 1919. Print. Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim. Lessings Werke: Laokoon. Charleston, South Carolina: Nabu Press, 2010. Print. Schlegel , Friedrich Karl Wilhelm. Kritische Schriften. Munich: Hanser Verlag, 1958. Print. Winkelmann, Johann Joachim. Gedanken ueber die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke, in der Malerei und der Bildhauerkunst. Stuttgsrt: Reclam Verlag, 1986. Print. ------------- Geschichte des Alterstums. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1993. Print. 14