A. Specific Aims

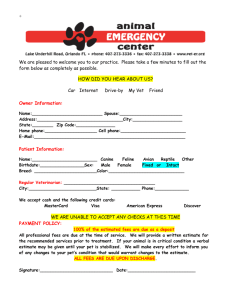

advertisement