T H C

advertisement

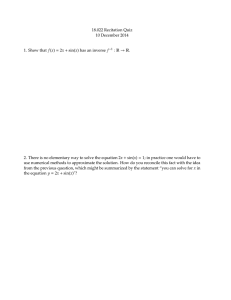

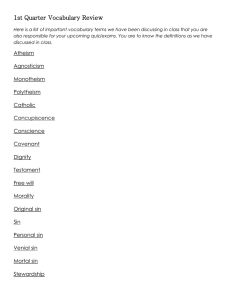

THE HUMAN CONDITION A. WHAT IS “THE HUMAN CONDITION”? 1. 2. 3. 4. Blaise Pascal, 17th century A.D. Marcus Aurelius, 2nd century A.D. The Buddha, 5th century B.C. Erich Fromm, 20th century A.D. B. WHAT IS THE CAUSE OF OUR CONDITION? 1. Original Sin 2. Three Effects of Original Sin a. concupiscence b. wounded intellect c. death C. THE MYSTERY OF DEATH 1. Why is it important? 2. How do human beings respond to death? a. death is natural b. death is absurd D. FOUR BELIEFS ABOUT THE AFTERLIFE 1. annihilation 2. disembodied immortality 3. reincarnation/nirvana 4. resurrection WHAT IS THE “HUMAN CONDITION”? Homo sum. Nihil humani a me alienum puto. --Terence Human condition is a specific term in philosophy. It means the situation, or condition, in which every human being finds himself or herself by virtue of being human. What experiences do all human beings share, regardless of their sex, age, culture, religion, social status, or the time period in which they live? We start with “the human condition” for good reason. If we are going to seriously consider the possibility that faith is the answer to our needs, we first must be clear what our needs are. And since Christianity claims that Christ is the answer for all peoples, we must examine especially those needs which are universal in our species. It cannot be denied that man is by nature a religious being. The simple observation that the vast majority of the human race feels compelled to worship a higher power, and has done so since earliest days, prompts us to wonder what it is about religion that satisfies us, and whether, as most religions assert, there is in fact some kind of otherworldly reality that affects our lives. But there is more to studying the human condition than that. A study of the human condition can console us, because we realize that we are not alone. All those thoughts, feelings, fears and desires running around in my head which I always thought were mine alone, or which I was afraid to talk about because they seemed a little strange, turn out to be part of almost everyone’s experience. Being able to name your demons may not make them go away, but realizing that others share them can bring great comfort. Studying the human condition is also important because it helps us to realize just how relevant and important religion really is for our own lives. To begin, we can do no better than read what some others had to say on the subject. Blaise Pascal, philosopher and mathematician, was one of the great geniuses of the Enlightenment. He wanted to write a book describing the human condition, and how it supported Christianity. Whenever he got an idea he scribbled it on a scrap of paper and stuck it in his pocket. He died a young man, long before he was able to finish the book. But shortly after his death, his friends were cleaning out his room when they found hundreds of pieces of paper piled on his desk and floor. They compiled them into a book and gave it the title Pensées, French for “thoughts”. It became one of the great classics of Western literature. Here are a few excerpts: 24 Man’s condition. Inconstancy, boredom, anxiety. 36 Anyone who does not see the vanity of the world is very vain himself. So who does not see it, apart from young people whose lives are all noise, diversions, and thoughts for the future? But take away their diversion and you will see them bored to extinction. Then they feel their nullity without recognizing it, for nothing could be more wretched than to be intolerably depressed as soon as one is reduced to introspection with no means of diversion. 47 Let each of us examine his thoughts; he will find them wholly concerned with the past or the future. We almost never think of the present, and if we do think of it, it is only to see what light is throws on our plans for the future. The present is never our end. The past and the present are our means, the future alone our end. Thus we never actually live, but hope to live, and since we are always planning how to be happy, it is inevitable that we should never be so. 70 If our condition were truly happy we should not need to divert ourselves from thinking about it. 133 Diversion. Being unable to cure death, wretchedness and ignorance, men have decided, in order to be happy, not to think about such things. 134 Despite these afflictions man wants to be happy, only wants to be happy, and cannot help wanting to be happy. 148 All men seek happiness. There are no exceptions. However different the means they may employ, they all strive toward this goal. The reason why some go to war and some do not is the same desire in both, but interpreted in two different ways. The will never takes the least step except to that end. . . . Yet for many years no one without faith has ever reached the goal at which everyone is continually aiming. All men complain: princes, subjects, nobles, commoners, old, young, strong, weak, learned, ignorant, healthy, sick, in every country, at every time, of all ages, and all conditions. . . . 198 When I see the blind and wretched state of man, when I survey the whole universe in its dumbness and man left to himself with no light, as though lost in this corner of the universe, without knowing who put him there, what he has come to do, what will become of him when he dies, incapable of knowing anything, I am moved to terror, like a man transported in his sleep to some terrifying desert island, who wakes up quite lost and with no means of escape. Then I marvel that so wretched a state does not drive people to despair. I see other people around me, made like myself. I ask them if they are any better informed than I, and they say they are not. Then these lost and wretched creatures look around and find some attractive objects to which they become addicted and attached. For my part I have never been able to form such attachments, and considering how very likely it is that there exists something besides what I can see, I have tried to find out whether God has left any traces of himself. 200 Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed. There is no need for the whole universe to take up arms to crush him: a vapour, a drop of water is enough to kill him. But even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his slayer, because he knows that he is dying and the advantage the universe has over him. The universe knows none of this. Thus all our dignity consists in thought. It is on thought that we must depend for our recovery, not on space and time, which we could never fill. Let us then strive to think well; that is the basic principle of all morality. 595 Unless we know ourselves to be full of pride, ambition, concupiscence, weakness, wretchedness, and unrighteousness, we are truly blind. And if someone knows all this and does not desire to be saved, what can be said of him? 1 1 Pascal, Blaise. Pensees. Trans. A. J. Krailsheimer. (London, Penguin Books, 1966). Remember that we want to name those things that everyone experiences. Thus, if Pascal’s description of the human condition is accurate, it should resemble what others have written at other times. This is in fact the case. The following is an excerpt from Meditations, philosophical musings by the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. He was not influenced by Jewish or Christian thought. III.3. Hippocrates cured many diseases and then died of disease himself. The Chaldeans foretold many deaths and then their own death overtook them. Alexander, Pompey, and Julius Caesar many times utterly destroyed whole cities, cut down many myriads of cavalry and infantry in battle, and then came the day of their own death. Heraclitus, as a natural philosopher, spoke at great length about the conflagration of the universe; he was a victim of dropsy, covered himself with cow dung, and died. Democritus was killed by vermin, and Socrates by another kind of vermin. What does it mean? 10. Small is the moment in which each man lives, small too the corner of the earth which he inhabits; even the greatest posthumous fame is small, and it too lives upon a succession of short-lived men who will die very soon, who do not even know themselves, let alone one who died long ago. 32. Consider, for the sake of argument, the times of Vespasian; you will see all the same things: men marrying, begetting children, being ill, dying, fighting wars, feasting, trading, farming, flattering, asserting themselves, suspecting, plotting, praying for the death of others, grumbling at their present lot, falling in love, hoarding, longing for consulships and kingships. But the life of those men no longer exists, anywhere. Then turn to the times of Trajan; again, everything is the same, and that life too is dead. Contemplate and observe in the same way the records of the other periods of time, indeed of whole nations: how many men have struggled eagerly and then, after a little while, fell and were resolved into their elements. 24. Alexander the Great and his groom are reduced to the same state in death. VII.21. You will soon forget everything. Everything will soon forget you. 2 Or consider the First Noble Truth of Siddhartha Gautama—commonly known as the Buddha— who lived in India six centuries before Jesus. His insight that “all life is suffering” is a basic principle upon which Buddhist philosophy is based. Huston Smith writes: The first noble truth is that life is dukkha, usually translated as “suffering.” . . . At the core-not of reality, we must remember, but of human life--is misery. That is why we constantly try to distract ourselves with ephemeral pursuits, for to be distracted is to forget what, in the depths, we are. . . . To get the exact meaning of the First Noble Truth, we should read it as follows: Life in the condition it has got itself into is dislocated. Something has gone wrong. It has slipped out of joint. As its pivot is no longer true, its condition involves excessive friction (interpersonal conflict), impeded motion (blocked creativity), and pain. 3 2 Aurelius, Marcus, The Meditations. Trans. G.M.A. Grube. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983) 3 Smith, Huston, The Religions of Man. (New York: Harper & Row, 1958) pp.110-112. Erich Fromm was a student of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, and is widely considered one of the pre-eminent psychoanalysts of the twentieth century. He describes the human condition using ideas we covered in the first chapter. Man is gifted with reason; he is life being aware of itself; he has awareness of himself, of his fellow man, of his past, and of the possibilities of his future. This awareness of himself as a separate entity, the awareness of his own short life span, of the fact that without his will he is born and against his will he dies, and that he will die before those whom he loves, or they before him, the awareness of his aloneness and separateness, of his helplessness before the forces of nature and of society, all this makes his separate, disunited existence an unbearable prison. The experience of separateness arouses anxiety; it is, indeed, the source of all anxiety. . . The deepest need of man, then is the need to overcome his separateness, to leave the prison of his aloneness. . . Man—of all ages and cultures—is confronted with the solution of one and the same question: the question of how to overcome separateness, how to achieve union, how to transcend one’s own individual life and find atonement.4 Perhaps you think these thinkers focus too much on the negative side of things, but it’s hard to deny the truth of what they’re saying. Here’s a list of the things they mentioned, plus some others, all of which can be said about virtually everyone. --the desire for happiness --ignorance --boredom --pessimism (we’re more inclined to see the bad than the good) --anxiety (we feel vaguely nervous, restless, uneasy) --dread (we fear our own freedom to choose something) --neediness --loneliness (part of us always feels lonely, no matter how many people love us) --alienation (part of us always feels separated and misunderstood) --pain (physical and emotional) --freedom (we must make tough choices with limited knowledge) --concupiscence (we do things that we know we don’t really want to do) --death WHAT IS THE CAUSE OF OUR CONDITION? We have a rather odd existence. Imagine yourself in the place of an alien visitor to Earth observing humans for the first time. After witnessing the kinds of things listed above —inescapable boredom, anxiety, loneliness, pain—it would be hard not to get the impression that the human race is “broken” in some way. At the very least, all of us must agree that human beings do not have an ideal existence. Now here’s another question. Where in the world did we get this notion of an “ideal” existence in the first place? If all these things are a natural part of what it means to be human, then why do we fight against them? There’s a part of us that believes we shouldn’t have to experience these things. 4 Fromm, Erich, The Art of Loving. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956) pp.8-9. But how is that possible, if they’re an inescapable part of the human condition? If you examine various myths, religions, and philosophies around the world you will notice a fascinating pattern. Many of them believe(d) that there was a time in the past when the human condition was not always so bleak. Recall Huston Smith’s description of Buddhism: “To get the exact meaning of the First Noble Truth, we should read it as follows: Life in the condition it has got itself into is dislocated. Something has gone wrong. It has slipped out of joint.” (If something has gone wrong, it implies a time when it was once right!) Likewise, the Greek myth of “Pandora’s Box” tells about a time when evil did not exist. Or consider the Hindus, who believe that a person’s truest self— the spiritual core or Brahman inside him that seeks perfect happiness—is unable to find its full expression because the world is now warped by sin, distractions, and disordered desires. And then there were the ancient Hebrews, who described a similar belief with the story of Adam and Eve being expelled from paradise. Blaise Pascal wrote: 117 Man’s greatness is so obvious that it can even be deduced from his wretchedness, for what is nature in animals we call wretchedness in man, thus recognizing that, if his nature is today like that of the animals, he must have fallen from some better state which was once his own. 148. What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself. 400 Man does not know the place he should occupy. He has obviously gone astray; he has fallen from his true place and cannot find it again. He searches every-where, anxiously but in vain, in the midst of impenetrable darkness. 401 We desire truth and find in ourselves nothing but uncertainty. We seek happi-ness and find only wretchedness and death. We are incapable of not desiring truth and happiness and incapable of either certainty or happiness. We have been left with this desire as much as a punishment as to make us feel how far we have fallen. The Christian Doctrine of Original Sin Christians share the belief that man once existed in a world untouched by evil, but introduced it through their sin. This belief is called “Original Sin,” and it constitutes one of the fundamental doctrines of the Christian faith. Christians believe that when humans first appeared on the earth (we’ll get to the question of evolution later), our relationship with God was very close, because there was no sin separating us. It was easy for humans to know and love him. God cannot create anything flawed, so humans did not experience anxiety, loneliness, boredom, concupiscence, or even physical death! Incredible as it sounds, we were not meant to die. This primeval state-of-being Christians call original justice. Then at some point, probably soon after humans first appeared, someone committed the first sin. It drove a wedge between us and God, rupturing our intimate relationship with him. To be honest, no one is really sure what that event looked like. All we can say is that the first sin alienated ourselves from everything—God, nature, each other—so that our lives became filled with sadness and pain. Human death entered the world. Christians call this mysterious event the Fall of Man. How could one sin cause so much damage? Imagine what would happen if you introduced foreign bacteria or insects into a perfectly balanced ecosystem. In theory it would radically disrupt the entire food chain, creating shortages in some places and an over-population of certain species in others. Nothing would escape untouched. One can imagine something similar happening if a single sin were introduced into a pristine environment. Or consider an island on which ten perfectly happy married couples live. Each person trusts his or her spouse completely; so much so that the thought of infidelity doesn’t even cross their minds. Then a mysterious stranger arrives on the island and seduces one of the persons. When the spouse finds out, their marriage will never be the same. They may forgive each other, but the memory and effects of that infidelity will linger. But more than that, what happens when the other nine couples find out what happened? For the first time each spouse will look suspiciously at the other and say, “Well, if so-and-so was unfaithful, maybe you will be too!” In this way all ten marriages are damaged by the act of a single person. The damage is not solely psychological. We all know that a person’s mental health affects his physical health, and vice-versa. The emergence of distrust, tension, doubt, and anxiety on the island would instigate physical illnesses as well, not only for the couples, but for their future children. Sin spreads like a disease and damages everything it touches. There is no such thing as a private sin; everything we do, no matter how small, has ramifications more widespread than we can possibly imagine. It is one of the great lies of our culture that the sins you commit in secret hurt no one but you. The term original sin refers to the fallen state-of-being, or damaged human condition, in which we exist as a result of the Fall. Any child born on our hypothetical island will have to grow up in a family whose relationships were damaged by the actions of a person he doesn’t even know. All of us are born into a world warped by sin and confusion. It is an inescapable part of our lives. We are born “wounded” by concupiscence and other deformities, which make it nearly impossible to avoid committing personal sins. Original Sin does NOT mean that babies are guilty of personal sins and need to be forgiven!! This is a common misunderstanding that gets people into trouble. St. Paul explained original sin in a letter he wrote to the Christians living in Rome about 57 A.D. In the following passage, when he refers to “sin,” he has in mind original sin more than a person’s individual sins. Therefore, just as through one person sin entered the world, and through sin, death, and thus death came to all, inasmuch as all sinned. . . But death reigned from Adam to Moses, even after those who did not sin after the trespass of Adam, who is the type of the one who was to come. For if by that one person’s transgression the many died, how much more did the grace of God and the gracious gift of the one person Jesus Christ overflow for the many. 5 The story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden, found in the third chapter of Genesis, was written about 600 B.C. by an exiled Hebrew in Babylon. He didn’t invent the story himself; rather, he was the first to put down on paper an ancient story that had been passed down orally for generations among his people. Genesis 3 tells the historical truth of the Fall using symbolic imagery.6 In other words, Catholics do not have to believe that there was literally a couple named Adam and Eve who listened to a real snake and were expelled from a real garden named Eden. Instead, the sacred story describes in symbolic terms an event which really happened at a specific moment in the past. This is why we call the Fall a “historical truth”. We don’t know most of the details about what actually happened—the who, where, and when—but the story does give us a clue about the important thing: why it happened. The first sin was motivated by pride. The first sinner (symbolized by Adam) was discontent with being human; he or she wanted to be like God (symbolized by eating from the tree of knowledge). He or she believed it was possible to get along just as well without God. 5 Romans 5: 12a, 14-15 6 C.C.C. #390 An Allegory for Original Sin Original Sin is a very abstract concept in some ways, so an allegory might help you understand some basic points. Imagine a fly buzzing through a park. It darts from one picnic site to the next, tasting all the food humans leave lying around. Life couldn’t be better than this as far as the fly is concerned. To soar through the air, without demands or obligations, to see the world through fly-eyes with a 360 degree field of view, to eat what he wants, when he wants--this is what it means to live! The fly feels a profound sense of gratitude at the realization that there is probably nothing in the world finer than being a fly. Later that day he’s thoroughly engrossed in tormenting a zebra at the zoo when he spots an open can of paint which a custodian left near the cage. He wanders over to investigate and accidentally falls into the can. This would be a traumatic experience for any fly, so we’ll call it “The Fall”. The fly treads the surface of the paint looking for a way out, but soon discovers that he is trapped. He crawls up the side of the can, but slides back down. Paint gums up his wings so that he cannot fly, and stains his eyes so that everything appears blurry and red. Worst of all, the fly realizes with a growing horror that he cannot help inhaling paint fumes. He grows nauseous and disoriented. Eventually the fly concedes defeat; there is simply no way out of the can. He decides to raise a family there. When his offspring arrive, however, they are no better off than he. Their genetics are mutated due to the fumes their father ingested, and their eyes and wings, like their father’s, are unable to function properly. As time passes a fly-civilization forms in the can. Each fly hates the paint, and most have differing opinions about the best way to get rid of it. They know it robs them of their happiness; and yet, in a weird sort of way, they’re attracted to the paint too. They’ve existed in the paint so long they actually began to like the taste of it. They know they shouldn’t; and in their better moments they’re absolutely convinced that paint is the source of everything hateful and harmful in their lives--but on the other hand, they’re so comfortable with it that they don’t mind swimming in it and throwing it at each other when they’re angry. The notion of a world without paint both attracts them and scares them. The first fly eventually dies. Generations come and go. Young flies grow up hearing strange stories about a primeval time when what it meant to be a fly was far different from what it means now. According to the legend, the first fly could fly through the air, though the young flies have only the vaguest idea what “flying” means. Supposedly he could also see the world in a hundred different colors, although they don’t really comprehend “color” either, since all they’ve ever known is red. Most incredible of all, the legend says that their original home was something inconceivably glorious compared to what they now have in the can. Many flies are skeptical. “Our race has always lived in the can,” they say. Others can’t believe their ancestors had it so lucky, and are tempted to regard the stories as silly fiction. But every so often, there appears among them a fly renowned for his virtue. He is able to cleanse himself of paint, not completely, but just enough to free his wings a little or clear his eyes. He can even buzz short distances. When these flies look up, they claim to see a world above the can, something the others cannot see. Some flies believe them. Others laugh. Still others wonder if these flies aren’t a hint of what their ancestors might have been like. What can we say about these flies after the Fall? First, being red is an inescapable part of their lives. Second, the paint prevents them from doing everything that comes naturally to flies: flying, multi-colored vision, breathing clearly, etc. They’re unable to fully express what it means to be a fly. For this reason, it would be wrong to say that being red is “essential” to being a fly, or that being red is a natural part of “fly-nature”. Just the opposite, in fact: all the flies in the can are less-than-flies. Only the first fly (before the Fall) was a fly in the fullest sense. Christians believe humans exist in a similar situation. When our ancestors first appeared on the earth they were able to express their humanity to the fullest. They were unblemished by sin. After the Fall, our minds and bodies and the world itself were thrown out of joint, so that now we’re unable to enjoy what should be ours. We are forced to live with the effects of sin; and what is more, it’s virtually impossible not to commit more sins of our own, not only because we’re covered in it already, but also because, in a weird sort of way, we find sin attractive. It is hard to imagine our lives without it. The idea of being a saint both attracts and repels us. Sin is not part of human nature! It is not essential to being human. If sin were an essential part of our humanity, we would have to call ourselves intrinsically (basically, at the core) evil, and thus conclude that God created us that way. But God, being perfectly good, cannot create anything evil. We are created good, and even though we sin, we are still intrinsically good. [Original sin] is a deprivation of original holiness and justice, but human nature has not been totally corrupted: it is wounded in the natural powers proper to it; subject to ignorance, suffering, and the domination of death; and inclined to sin—an inclination to evil that is called ‘concupiscence.’7 Some Christians are uneasy about original sin because they think it cannot fit with evolution; and some Christians don’t believe in evolution because they suppose it cannot be reconciled with original sin. We will address the question about evolution and Christian faith later. For now, I ask you to consider these three things which Christians believe are a result of original sin. Concupiscence. Have you had the experience of knowing that something was wrong to do; you admitted to yourself that it was wrong; you told yourself that you didn’t really want to do it; and that if you did you would regret it--and then you went and did it anyway? And then you cursed yourself, “Damn, damn, damn!! Why did I do that?!” If you’ve ever done this, rest assured that you’re not crazy, and you’re not alone. Now think about it: doesn’t that experience tell you that something is disordered inside you? How can you be at war with yourself, unless something is screwed up? St. Paul could sympathize. To the Christians in Rome he wrote: I do not understand what I do. For I do not do what I want, but I do what I hate. . . . Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me. So, then, I discover the principle that when I want to do right, evil is at hand. For I take delight in the law of God, in my inner self, but I see in my members another principle at war with the law of my mind, taking me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. Miserable one that I am! Who will deliver me from this mortal body? 8 Concupiscence means that even though human beings desire goodness, we are mysteriously attracted toward evil. We don’t want to do bad things, but something draws us nonetheless, and then we feel guilty afterward. The main consequence of concupiscence is that our good intentions by themselves are not enough to save us from our human condition. Wounded Intellect. Consider a young man whose family lives in an affluent neighborhood, and where he is sheltered from exposure to people of any race except his own. His parents pride themselves on raising their son to never judge a person by the color of his or her skin. But they also teach him never to step foot in the city because it’s dangerous (except of course when there’s a ballgame downtown), and they encourage him to oppose plans to run a public train line through their community, because certain people shouldn’t have easy access to their neighborhood (although they would be offended if you pointed out to them who those “certain people” are). The parents also advise him never to give money to beggars, because they could get a job if they really wanted one. 7 C.C.C. #405 8 Romans 7:15, 20-24 How will experiences like these affect his adult life? He may be the most rational person in the world when discussing politics, religion, or sports; but if you broach the topic of race-relations or the poor, you’ll likely see his rational thinking dissolve into a morass of unsubstantiated opinions about the city and its poorer citizens. Given his past experience, it’s easy to see why he would think this way. In his mind he’s being perfectly rational, and, to his credit, he would be horrified at the suggestion that his views were based on racial stereotypes and naivete. Nevertheless his experience of ignorance, fear, and subtle racism—in short, his experience of evil—has warped his thinking. Catholicism maintains that everyone’s thinking has been damaged by the effects of original sin. Our intellects are warped--not completely--but enough to make our search for truth more difficult. Another way to understand the idea a “wounded intellect” is that the proper balance between our emotions, desires, and intellect has been thrown out of whack by original sin. Emotions often overrun what we know is true. We may know that taunting another human being is cruel, but when the crowd is doing it, our fear of rejection overrides our conviction, and we participate in the taunting. Similarly, we may believe that Christianity is true, but when temptations arise, it often becomes easier to simply forget about the faith. Though human reason is, strictly speaking, truly capable by its own natural power and light of attaining to a true and certain knowledge of the one personal god, who watches over and controls the world by his providence. . . yet there are many obstacles which prevent reason from the effective and fruitful use of this inborn faculty. For the truths that concern the relations between God and man wholly transcend the visible order of things, and, if they are translated into human action and influence it, they call for self-surrender and abnegation. The human mind, in its turn, is hampered in the attaining of such truths, not only by the impact of the senses and the imagination, but also by disordered appetites which are the consequences of original sin. So it happens that men in such matters easily persuade themselves that would they would like to be true is false or at least doubtful. 9 The consequences of a wounded intellect? Philosophy alone will not save us from our human condition. Death Enters the World. The most terrible effect of original sin is also the most difficult to imagine: that death—at least human death—did not always exist. Christians believe that during the period of original justice, before the Fall, humans were not destined to die. At first glance this seems ridiculous. Given what we know of biology and evolution, can anyone take this belief seriously? We will address this question later, when we discuss the relationship between science and faith. For now, I ask you to put your doubts on hold for a moment, and consider the ways in which human beings respond, and have responded, to the mystery of death, and how it leads one to wonder about God. THE MYSTERY OF DEATH Out, out, brief candle! --Shakespeare There is one question of such staggering importance that most people are too scared even to think about it. That question is whether death is the end of every-thing, or the beginning of eternal life. Can you imagine anything more important than knowing whether or not you will live forever? 9 C.C.C. #37; as quoted from Pius XII, Humani Generis, 561: DS3875. Stop and think for a moment what that means. Immortality! Is it even possible? Is there anything more that anyone can hope for? Or, on the other hand, could death mean that we cease to exist, a falling asleep at which we lose consciousness, never dreaming or experiencing anything ever again? It is impossible to imagine yourself not-existing. Try it and see. Close your eyes and try to imagine what it’s like to be asleep but not dreaming. Shut out all thoughts, images, and feelings. You will soon discover that it is impossible, because by the very act of thinking about yourself as notexisting, you are still thinking. You cannot escape your own thoughts. Now try to imagine yourself living forever. It is almost as difficult to do--almost, but not quite. We can barely imagine ourselves living forever, as long as that means perfect happiness. But if immortality means experiencing the same kind of life we have now for eternity, then eternal life is the scariest thing in the world! Who wants to live this kind of life forever? When you try to imagine yourself as not-existing, you are trying to imagine the possibility of annihilation, which means that after death you are reduced to nothingness. Your body decays into its constituent particles and your mind loses self-consciousness, which is like falling into a dreamless sleep and never waking up. When you contemplate living forever, you are imagining the possibility of immortality, which means you keep both self-consciousness and your individual personality. Either possibility is frightening, but one of them must be true! Whichever you believe, it should profoundly affect the way you live right here and now. We will say more about that in a moment. Blaise Pascal lived during the Enlightenment, a time when people believed that reason, given enough time, could answer all questions and solve all problems. Religion was dismissed as a waste of time. Who needs God to solve your problems if reason can do it for you? Pascal’s friends felt this way. They were mathematicians too, and they used their skills in the casinos, where they spent their free time gambling, carousing, and making fun of religion. They tried to convince Pascal that he was wasting his time on religion. Pascal couldn’t believe it. How could they blow-off religion as unimportant, when it claimed to have the answer to the greatest of all mysteries? The immortality of the soul is something of such vital importance to us, affecting us so deeply, that one must have lost all feeling not to care about knowing the facts of the matter. All of our actions and thoughts must follow such different paths, according to whether there is hope of eternal blessings or not, that the only possible way of acting with sense and judgment is to decide our course in the light of this point, which ought to be our ultimate objective. Thus our chief interest and chief duty is to seek enlightenment on this subject, on which all of our conduct depends. And that is why, amongst those who are not convinced, I make an absolute distinction between those who strive with all their might to learn and those who live without troubling themselves or thinking about it. I can feel nothing but compassion for those who sincerely lament their doubt, who regard it as the ultimate misfortune, and who, sparing no effort to escape from it, make their search their principal and most serious business. But as for those who spend their lives without a thought for this final end of life and who, solely because they do not find within themselves the light of conviction, neglect to look elsewhere, and to examine whether this opinion is one of those which people accept out of credulous simplicity or one of those which, though obscure in themselves, nonetheless have a most solid and unshakeable foundation: as for them, I view them very differently. This negligence in a matter where they themselves, their eternity, their all are at stake, fills me with more irritation than pity; it astounds and appalls me, it seems quite monstrous to me. Would you act any differently than you do now if you knew death would be the end? Because if death is the end, any happiness must be found in this life. It wouldn’t make sense to suffer fools gladly, or waste an hour of your week at Mass, or endure more sacrifices and hardships than absolutely necessary. But if death is not the end, that changes everything, doesn’t it? We might be willing to forego certain pleasures and opportunities in this life, in exchange for greater joys in the next. Imagine a married couple in their thirties who have no children. They care about each other, but the happiness has gone out of their marriage. They no longer enjoy each other’s company because their interests have grown so far apart that they have little to talk about anymore. To be sure, they are not unkind to each other, and they rarely fight. But they’re simply bored. Then the husband falls in love with another woman who shares his interests, and the wife finds another man who makes her happy. What should the couple do? If there’s no afterlife, then their only shot at happiness is limited to the forty-odd years they have left to live. Is there any reason for them not to divorce and remarry? But what if they know they will live forever? In this case, is it possible that fidelity to their marriage vows—even though it means being bored—will prepare them for the next life by teaching them the true nature of love and commitment? Unquestionably, whether or not you believe you will live forever should guide everything you say and do. It is the great choice which every intellectually honest person is forced to make. Thus it is a perennial theme for the world’s greatest poets and writers. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, for example, the Danish prince is faced with a terrible decision. Should he take violent revenge on the king, whom Hamlet suspects killed his father? Hamlet doesn’t know what to do, because he doesn’t know whether he will be held accountable in the next life--if there is one. He wonders to himself: Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing, end them? To die; to sleep; No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to, ‘tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep; To sleep? perchance to dream. Ay, there’s the rub; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil Must give us pause. [endure] [terrible luck] [pains] [end] [be conscious after death] [earthly life] [make us think twice] Notice Hamlet mentions the two possibilities we discussed earlier. First he considers the possibility of annihilation: “to die, to sleep, No more”; then he considers the possibility of immortality: “to die, to sleep, perchance to dream”. Either possibility is frightening, but one of them must be true, and Hamlet knows that whatever he chooses must guide his actions. You might object to the assertion that there are only two possibilities regarding the afterlife. What about reincarnation? Yes, there are other theories, but if you examine them closely, you will see that in the end, what they offer is still either annihilation or immortality. To see why this is so, we will shortly consider the four major beliefs regarding the afterlife. For now, let’s continue to examine how human beings respond to the mystery of death. The first thing anyone notices when he or she contemplates death are the two radically different attitudes we bring to it. At times we view death as perfectly natural, in keeping with our nature as organic life forms, all of which break down and cease to function, and whose decayed bodies are absorbed by the ecosystem for the next generation of animals. The feeling that death is natural is supported by what you’ve probably heard older people say—maybe even your grandparents—that they look forward to dying. Often this is because they are in pain, or because they miss their spouse who died before them. Marcus Aurelius wrote: What is the nature of death? When a man examines it in himself, and with his share of intelligence dissolves the imaginings which cling to it, he conceives it to be no other than a function of nature, and to fear a natural function is to be only a child. Death is not only a function of nature, but beneficial to it.10 Nevertheless, most people would agree that Aurelius’ view is a little one-sided. Human beings cannot help viewing death as an enemy, a tragedy, an absurdity. The reason is that death frustrates certain aspects of what it means to be human. When a squirrel dies--assuming it enjoyed a normal lifespan--it has accomplished everything it means to be a squirrel. It buried nuts, climbed trees, mated and made little squirrels. There was nothing else left to do, because a squirrel’s normal activities are limited to these things. The same can be said for all animals. Human beings, however, always die unfulfilled. No matter how long a person lives, and no matter how much he or she accomplishes, he or she always regrets not being able to do more, to experience more, to learn more, to love more. A person dies having accomplished only the tiniest part of what he could have done had he lived longer. Mozart died when he was only forty. Can you imagine what we would have today had he lived another forty? Another sixty? Another hundred? Einstein died trying to reconcile quantum physics with general relativity. Where would we be today had he lived another ten years? There comes a time when one asks, even of Shakespeare, even of Beethoven, “Is that all there is?” --Jean-Paul Sartre The human fear of death is deepened by the threat it poses to our very existence. We are creatures conscious of ourselves and the world around us. We can experience goodness and beauty, and when we do experience these things, they cause us to rejoice in not only in their existence, but in ours, since our existence makes it possible to appreciate them. A man who loves nothing, cares for nothing, appreciates nothing, does not fear death. Why should he? He has nothing to lose. But for the one who knows the joy of loving and being loved, death can only be viewed as an enemy which takes everything away. Dylan Thomas was a Welch poet who watched his father die of old age. Thomas could not bear the thought of never seeing him again, and so wrote these lines for him: Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. 10 The Meditations, II. 12. Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light. A third reason death is unnatural is that it terminates human growth before it ever reaches its goal. When a caterpillar becomes a butterfly, it accomplished what it set out to do. Its growth process is complete. Likewise, when an acorn becomes a tree, it reached its goal. All growth by definition is growth toward something. Now, a person also undergoes growth. His life is marked by one continuous process of learning how to love. He enters into a multitude of relationships with family and friends, spouses and children, for this very reason. In these relationships he makes mistakes, tries again, says stupid things, has his challenges, his setbacks, his failures, and hopefully, his great successes. Then, just when it comes to the point that he finally begins to understand what it means to love unreservedly, death comes along and chops it off at the knees. Ostensibly, it renders human existence absurd (meaningless), because the person never reaches the end for which he has been striving. If death is the end, human beings are the only creatures on earth who cannot reach their goal. Is death natural or absurd? From the Christian point of view man’s conflicted attitude on this point is perfectly understandable. Remember, original sin says that everyone suffers and dies, so it makes sense that death would seem natural, and that some people would welcome it to escape their pain or loneliness. But for a person who is free of pain and enjoying life to the fullest, death is anything but welcomed. Original sin says that in the beginning death was not part of the ideal plan for humans, which explains why, when people are living a relatively ideal life, death seems so intrusive and out-of-place. FOUR THEORIES OF THE AFTERLIFE Annihilation (Latin nihil = nothing), again, is the belief that death means falling into a dreamless sleep from which you never wake up. Some philosophers describe it as the void. Nonbeing. Nothingness. Or what Ernest Hemingway called (in Spanish), the Nada. The Hebrews of early Old Testament times shared this view. They believed it was gift enough that Yahweh brought them into existence in the first place, and that it would be presumptuous to ask for anything more. Nevertheless, the Hebrews still expressed a longing to survive death--in this regard they are no different than almost all cultures at all times--but for them life after death was possible only in a symbolic sort of way: as long as a person was remembered by family and friends, he or she was never truly dead. That’s why Yahweh’s promise to Abraham that he would be the father of countless descendants meant so much to Abraham, who was afraid that he and his wife would die childless--remember, Sarah was sterile--and therefore be forgotten forever. If you read the Old Testament carefully, you will notice that several centuries before the birth of Christ the Jews began to change their minds about annihilation. They began to wonder whether the soul might in fact exist forever. What changed their thinking is open to speculation; some say the Jews were influenced by Greek and Roman philosophy; others say the Jews began to reconsider whether an all-good God would really give them the most wonderful gift in the world--existence-only to take it away again. In any case, by the time Jesus was born, the Jews were pretty evenly split in their beliefs. Jesus’ forceful teachings about the existence of heaven would have been very controversial to his listeners.11 Disembodied Immortality. Many people believe that the soul is immortal, which means that after death it separates permanently from the body, which decays, but the soul nevertheless continues to be self-conscious, and keeps some or all memories of its earthly life. The Greek philosopher Plato believed in something similar to this. He considered the body evil, because its desires, needs, and weaknesses distracted a person from his or her true purpose: being a philosopher. The goal of every person was to escape the limitations of the body as much as possible in order to find truth. In the next life, freed from the prison of the body, a person could contemplate eternal truths forever. Plato explained this view in his classic work on death and immortality, the Phaedo. Don’t you think that the person who is likely to succeed in [good philosophy] most perfectly is the one who approaches each object, as far as possible, with the unaided intellect. . . who pursues the truth by applying his pure and unadulterated thought to the pure and unadulerated object, cutting himself off as much as possible from his eyes and ears and virtually all the rest of his body, as an impediment which by its presence prevents the soul from attaining to truth and clear thinking? Is this not the person, Simmias, who will reach the goal of reality, if anyone can?12 Many Christians believe in disembodied immortality, because they mistakenly believe that this is what Jesus taught. In fact, he talked about something quite different. Reincarnation is the belief that a person’s soul leaves the body after death and enters another human body. It differs from “metempsychosis,” the belief that human souls enter plant and animal organisms as well. The notion of reincarnation originated independently in many different cultures, notably ancient Greece and India. It never caught on in Europe and soon died out in Greece, partly because it was difficult to defend on western philosophical grounds, and partly because it could not be reconciled with Christianity. These factors were absent in the Orient. Thus belief in reincarnation was more easily assimilated into Hinduism and Buddhism. Believers in reincarnation usually maintain that the kind of body a soul re-enters is determined by the quality of its past life. This quality is called “karma”. An immoral person with low karma is reborn into an insect or tree, while high karma is rewarded with another human body. The process of death and rebirth continues until the soul purges itself of all disordered desires and comes to the realization that there is no difference between itself and the universal soul, called Brahman. When that happens the soul experiences nirvana, a perfect blessedness in which one finally lets go of his illusion of individuality, and is absorbed into the universal soul. Resurrection is the Christian belief that, just as Jesus was raised soul and body from the dead, so too people will be raised soul and body to eternal life. Like Plato’s view, we retain individual identity and (presumably) some or all of our memories. But unlike Plato’s view, Christians believe that this body is an essential part being a human. It is holy, not evil, as Plato maintained. Therefore Christ will raise our mortal bodies on that last day and make them like his own: glorified and freed from all imperfections. 11 Matthew 22:23-33; Mark 12:18-27; Luke 20:37-39; Acts 23:8. 12 Phaedo 65e-66a The Church affirms that a spiritual element survives and subsists after death, an element endowed with consciousness and will, so that the “human self” subsists. To designate this element, the Church uses the word “soul,” the accepted term in the usage of Scripture and Tradition.13 The gospel writers took great pains to make it clear that their risen friend was not a ghost. Jesus ate and drank with the apostles (ghosts don’t eat and drink), he breathed on them (ghosts don’t breathe), he built a campfire and cooked breakfast for them (ghosts don’t cook breakfast), and he let Thomas stick a finger in the spear-gash in his side (ghosts can’t be touched). On the other hand, the apostles saw something very different about Jesus too. He could pass through locked doors (John 20:19), appear out of nowhere (Luke 24:36-37), and disappear again (Luke 24:31). Most telling, Jesus’ close friends sometimes did not recognize him when he first appeared to them (Luke 24:16, John 20:14, 21:4, Mark 16:12). He clearly had not returned to an earthly life per se.14 Although Christians have little idea what our glorified bodies will be like, Jesus’ own resurrection gives us a clue what we can expect. Exactly how this glorified state is to be thought of or imagined is not clear. Christ definitely stated that, after the resurrection, there will be no marrying or giving in marriage, and that we shall be like angels in Heaven. From the descriptions which we have of Our Lord’s appearances to His disciples after His resurrection, we are able to a certain extent to deduce the properties of this glorified state. As we have already said, the body will then be impervious to suffering, will be endowed with a clearness of vision which will make it, for the first time, completely itself, with agility by which it can penetrate everywhere with the utmost rapidity, and subtility by which the body becomes subject to the absolute dominion of the soul. It is only with the greatest reserve that we should picture to ourselves these things, for revelation only gives us an inkling here and there in obviously figurative language. We believe profoundly in the resurrection, we humbly expect it, but we only understand it in part. The resurrection should be the greatest consolation to man, who so loves his body, and should respect it as the willing instrument of his soul. 15 13 “Letter on Certain Questions Concerning Eschatology,” by the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Printed in L’Osservatore Romano (English Edition). N. 30 (591). July 21, 1971. 14 C.C.C. #999 15 Greenwood, John, Handbook of the Catholic Faith.