SILENT SPRING American Experience (PBS)

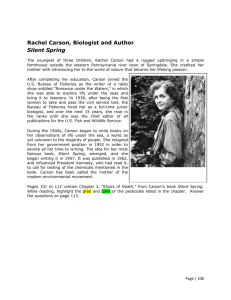

advertisement

RACHEL CARSON’S SILENT SPRING American Experience (PBS) Narrator: Alex Chadwick Readings by Meryl Streep David McCollough: A single book changes history only rarely. There was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, and Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed. And then there was Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. Rachel Carson began her work in the 1950s when it was extremely rare for a woman to speak with authority on any scientific subject. “Rachel Carson changed our lives, changed the way we think about the world and our place in it.” Crop-dusting Spraying suburbs and cities Spraying children at a picnic Spraying in an orchard. Carson reading from her book: “They [pesticides] should be called biocides.” Stewart Udall (former Sec. of the Interior): “The essence of Rachel’s message was that we have to come to terms with nature, to work with it and not against it.” “In the sense of a change in our thought, I think she was a revolutionary.” Carson at a speech: “The reporter continued, ‘No one in either county farm office who we talked to today had read the book, but all disapproved of it heartily.’” Carson won respect with earlier writings, particularly The Sea Around Us. She grew up in western Pennsylvania. She learned about nature from her mother. She always wanted to be a writer. At the Pennsylvania College for Women she majored in biology. She earned a Master’s Degree in zoology at Johns Hopkins. Shirley Briggs (former colleague): Her father and a sister died while she was in school. Carson went to work to support her mother and a sister. She went to work in 1936 at the US Fish and Wildlife Service as a writer. She was one of only two women in the FWS. Bob Hines (colleague) describes collecting specimens with Carson. Carson insisted on returning specimens alive to the spot from which they had been collected. RACHEL CARSON’S SILENT SPRING 2 1941: Carson wrote Under the Sea-Wind, which won widespread praise. Carson became editor of all Fish & Wildlife Service publications after WW II. She wrote The Sea Around Us in 1951. It became a best-seller. Readers knew nothing about her. Her picture was not on the cover. People were shocked to find that she was so small. Jeanne V. Davis (former colleague): “She was a feminist before her time.” “She didn’t let anyone push her around…. She had enemies because she didn’t compromise very easily. She spoke her mind and was rather blunt at times.” When her sister died, Carson adopted her son. Roger Christie (Carson’s adopted son): “She was my mother, too, after my mother died.” Carson built a house in Maine and another in Maryland. In The Sea Around Us, she railed against “the arrogance of man” for thinking “he” could change the laws of nature and make the earth obey. Roland C. Clement (former VP of the National Audubon Society): “We went into a binge in developing new chemicals [after WW II].” The most famous pesticide was DDT. John L. George (biologist): DDT was a military secret in WW II. “It was a very potent chemical for killing certain insects.” Thomas Jukes (biochemist): Wars ended because soldiers died of typhus carried by lice. But in WW II DDT spraying killed the lice and typhus fever was stopped. Following WW II DDT was used in civilian life. It was thought to be safe. Robert Rudd (zoologist, U.C. Davis): “There might be something here that isn’t quite as advertised.” The Fish and Wildlife Service was one agency that studied its possible drawbacks. Patuxent Research Laboratories 1945-55: pesticide use went from 125 million pounds to over 600 million. Suburbs were treated with DDT. Government endorsed the product, and industry pushed it. Their slogan seemed to be, “If a little is good, then a lot is better.” RACHEL CARSON’S SILENT SPRING In 1957, planes sprayed a Massachusetts bird sanctuary owned by Olga Huckins, a friend of Carson’s. Huckins told Carson that birds were being poisoned. Robert Cushman Murphy sued the USDA to stop spraying gypsy moths, but he lost. Carson’s articles against DDT were not published. Carson tried to get Reader’s Digest interested in DDT problems. They weren’t interested. Paul Brooks (editor & publisher at Houghton-Mifflin): Carson worked alone, then found a secretary, Jeanne Davis. Carson could not get information from the government, which insisted that all pesticides were safe. John George: The administrators [of USDA] were reluctant to give out information “because it might leave the impression that pesticides were dangerous.” Roland Clement: “I was up against industry and agricultural experiment station personnel who insisted that the way they used these chemicals they did no harm, and that the people who insisted otherwise were either misled or were being paranoid.” Shirley Briggs: “Some people she quoted in the book lost their jobs….” John George: “There was a mind-set against insects. They really focused on the bad ones, without realizing, I expect, ecologically, the vast control of insects is by other insects. But, you see, the moment you step in and play god with a chemical you get into problems.” Carson attacked the government for exaggerating the threat of insects, like the fire ant. — Government ads against the fire ant. Dieldrin is 40 times more toxic than DDT. It was used extensively in the South. Horses, cows, dogs, cats, and birds died. Carson wrote in long hand, then Davis typed the manuscript. TEPP was a German nerve gas. It was lethal to humans. It became the basis for Parathion. In 1960, Carson had put in two years of steady work on Silent Spring. The book grew from six to 17 chapters. Paul Brooks: Writing came hard to Carson. 3 RACHEL CARSON’S SILENT SPRING 4 Carson: “For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to dangerous chemicals from the moment of conception until death. The ‘control of nature’ is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man. It is our misfortune that so primitive a science has armed itself with the most modern weapons, and that in turning them against the insects, it has also turned them against the earth.” By March 1960, the book was almost finished. But she suffered many physical ailments. Then she had breast cancer, a radical mastectomy. Davis: She was in pain almost all of the time. She received regular radiation treatments. Carson: “I was as ill as I’ve been in my life.” She received radiation treatments and cortisone injections. “The only good thing in all this is that the long time away from close contact with the book may have given me a broader perspective. Now I’m trying to find ways to write it all more simply.” A colleague warned her that she “would be subjected to ridicule and condemnation.” Davis: “She loved every word she wrote.” The New Yorker serialized the manuscript in the spring of 1962. The book would be published in the fall. When she finished the manuscript she listened to Beethoven’s Violin Concerto [a portion accompanied by great pictures of nature!]. Robert Rudd: “What she was doing was adding a dimension [of beauty] to a technical argument….” Narrator: She “had called into question the integrity of the entire pesticide industry.” Velsicol tried to stop Houghton-Mifflin from publishing the book. Briggs: “Anyone who was opposed to pesticides was a tool of the communist menace.” Brooks: Velsicol was a threat to publication if we went ahead with it. It had already threatened The New Yorker for its publication of three early sections. John George: Secretary Udall was impressed by it. Pesticide overuse came up in a JFK press conference. Kennedy responded to a question, saying that the Dept. of Agriculture was looking into Carson’s allegations. RACHEL CARSON’S SILENT SPRING 5 The book was published on Sept. 14, 1962. It became a best-seller in two weeks. Udall championed Carson from the beginning. The chemical industry challenged the book. Briggs: “She was a bird-lover, or something.” Udall: “They tried to clobber her, beat her down with the weight of their opinions. And some of them were distinguished men.” Brooks: “It was attacked by the American Medical Association. It was attacked by Monsanto, who said, in effect, that we were turning the world over to the insects.” But the worst of all was when she wrote about the effect on future generations. One critic said, “She’s a spinster, isn’t she? What does she know about future generations?” Davis: “The chemical companies were really searching for some way to bring her down by proving that she was hysterical and didn’t know what she was talking about….” Brooks: The chemical industry’s attacks only provided more publicity. The harshest criticisms came from industry scientists, such as Robert White-Stevens. Thomas Jukes (critic of Silent Spring): “[White-Stevens] was a very eloquent person, a great speaker…. One of the bad things about the book was that it made people terrified about the pesticide residues in foods….” Clement: A public storm of this kind always accompanies the opening of an issue like this. Christie: “She was the good guy.” There were constant media interviews. Eric Severeid (CBS) did a special on Carson. Jay McMulland (producer): CBS got mountains of mail before the program aired. Most of it opposed the program, telling CBS to be sure to be fair. A lot of it was mimeographed. The two major sponsors pulled out. Carson (in the CBS program): “We have heard the benefits of pesticides. We have heard a great deal about their safety, but very little about the hazards, very little about the failures, the inefficiencies. And yet the public was being asked to accept these chemicals, was being asked to acquiesce in their use, and did not have the whole picture.” Robert White-Stevens: “The crux, the fulcrum over which the argument chiefly rests, is that Miss Carson maintains that the balance of nature is a major force in the survival of man, whereas the modern chemist, the modern biologist, the modern scientist believes that man is steadily controlling nature.” RACHEL CARSON’S SILENT SPRING 6 Carson: “Now, to these people, apparently, the balance of nature was something that was repealed as soon as man came on the scene, when you might just as well assume that you could repeal the law of gravity. The balance of nature is built on a series of interrelationships between living things and between living things and their environment.” Senator Abraham Ribicoff (R-Conn) announced Senate hearings on pesticides and their use. Ribicoff: “[Without] Rachel Carson I never would have had those hearings.” The government had a responsibility to step in. Narrator: “Carson knew that the only way to bring about lasting change was to encourage government to take a leadership role.” Ribicoff: “What people don’t understand is that Rachel Carson wasn’t for the complete outlawing of pesticides or chemicals to help agriculture. Her point of view was that it was over-abused, that it wasn’t used properly, that it wasn’t under control.” Silent Spring “forced people to think about the environment in a new way.” Udall: “Rachel Carson brought [the environment] out of the dark corner and put it up front…. I think she was revolutionary.” Narrator: Carson made “a powerful case for the inter-connectedness of all life.” Silent Spring was translated into 22 languages. In 1963, Carson went to Maine to be with close friends, Stan and Dorothy Freeman. Carson reflects on her impending death in a letter to Dorothy. “Most of all, I shall remember the monarchs….” Carson died two years after Silent Spring was published. Within a decade, sweeping environmental laws were enacted. Postscript in print: “As the world seeks to address environmental issues, more people are reading Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ than at any time before.”