You Can Write a Great Paper! ... Dr. Leininger’s Writing Guidelines

advertisement

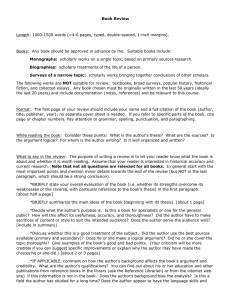

You Can Write a Great Paper! Dr. Leininger’s Writing Guidelines Page 1 of 5 What Message Are You Sending to Your Reader? Each of the items below encourages you to reflect on what message you send to your reader. For example, your title is like the first impression you make when you meet someone. If you don’t bother to give your paper a title or if you give it a title such as “Paper One” or “An Analysis of a Christian Perspective on War,” it signals to the reader that you don’t consider your work worthy of a good name. Conversely, when you provide a creative, attention grabbing title that points to a powerful thesis, you favorably dispose the reader to your work. After you have written your paper, evaluate how well your paper executes each of the numbered items below (unsatisfactory, satisfactory/good, very good, or outstanding). Your instructor will use these criteria in order to arrive at your grade. I. Introducing Your Argument: Making Your First Impression 1. Title: Hook Your Reader and Point to Your Thesis. Give your work a title that creatively hooks the reader and points toward your thesis. Message: Here is the first impression I want to give about my work. 2. Abstract: Map Out Your Argument. After you have written your paper, write a single-spaced abstract of your argument immediately after your title and before your opening paragraph using the following format (with the four underlined headings included). 1. Thesis. State the central point that you make in the paper (1-2 sentences). A strong thesis argues your particular interpretation or response to the ideas discussed. It should be specific (precise and clear rather than too broad or vague), contestable (worth arguing about, not simply stating the obvious), and supportable (can prove with evidence, is not merely an opinion). State your thesis in the form "I will argue" or "My examination will show" rather than "I will examine." 2. Support. List the 2-3 most important reasons that you will provide to support your thesis (1 sentence for each point; 2-3 sentences total). 3. Counterarguments & Rebuttal. State the strongest counterarguments to your thesis and your response to these counterarguments (State 1-2 counterarguments in 1-2 sentences and your responses in 1-2 sentences; 2-4 sentences total). 4. Road Map. List, in the order that they appear in your paper, the main steps you will take to advance your thesis (1 sentence or less for each step). These steps tell the reader what questions you will address in each part of your paper and preview your answers to these questions. They provide clear signposts that form the basis for the headings before each section of your paper. Here is an example of a road map: First, I explain Smith’s argument that globalization improves the plight of the poor by providing more and better jobs. Second, I draw upon John Paul II to argue that, because globalization in its dominant form reduces workers to a mere commodity, we need to develop a more humane form of globalization. Third, I address the counterargument that a more humane form of globalization is unrealistic and hypocritical because it expects third world countries to bypass the stages of industrialization that once characterized the economies of first world nations. Fourth, I show that the practical upshot of my argument is a call for a) consumer groups that monitor labor practices and b) alternative worker cooperatives such as the Mondragon Cooperative in Spain. Message: I have a well-thought-out argument that has a point (a thesis). You Can Write a Great Paper! Dr. Leininger’s Writing Guidelines Page 2 of 5 3. Introduction: Grab Your Reader’s Attention and Introduce Your Argument. Use an opening that readily establishes a connection with the reader and makes the reader want to read on. Next, briefly state what you will argue and why it matters. (You may, but need not, preview the major steps in your argument that were provided in your abstract). Message: This is worth reading and will be easy to follow. 4. Headings: Point to the Thesis of Each Section. Use headings (underlined or in bold) for each major step/part of the paper to signal to the reader where you are in the map and thus what will be argued in this section of the paper. A heading should indicate the connection between this particular section and the overall thesis of your paper. How do the headings in this handout help the reader? Message: My dynamic headings hook you into each section, make it easy for you to know its main point, and reinforce my overall thesis. II. Body & Conclusion: Arguing Persuasively & Demonstrating Deep Engagement 5. Paragraphs: Focus on One Main Point. Each paragraph should have a main point (or its own “mini-thesis”). This will be clearly stated in a topic sentence, i.e., a one sentence summary the overall point or purpose of this paragraph. Except for transitions connecting this paragraph to the preceding or next paragraph, each sentence in the paragraph should develop, explain, and support this main point. The purpose of a paragraph is break down your argument into easy digestible pieces. Find a paragraph length that develops your point adequately and is easy to read. Message: I have organized my ideas into easily digestible paragraphs whose sentences are all unified around a main point. 6. A Deep Learning Experience: Maximize Critical Analysis. Instead of taking the easiest route, write your paper in a way that will deeply engage the readings, concepts, and arguments and demonstrate the depth of your understanding and analysis. Maximize the amount of the paper devoted to critical evaluation and dialogue. One must first understand arguments accurately before evaluating them insightfully. How could one argue against your thesis and how would you respond? What would one author say to another? What points would they agree and disagree upon and why? What are the strengths and problems with the author's argument? What are the implications of the author's arguments? If true, then what follows? So what? Why should the reader care about your argument? If accepted, what practical differences might it make? Message: Like a pinball machine that has been lit up to score maximal points, every inch of this paper is lit up with thoughtful connections and analysis. 7. Argumentation: Evidence and Reasons Rather than Opinions or Feelings. Replace "I feel" or "My opinion is" with the evidence and reasons that support your position. Replace “I feel that the author is wrong” with “the author is wrong because . . .” (followed by arguments that support your position). Message: I do not simply assert opinions. Instead, I offer wellthought-out reasons to support my claims. 8. Make Your Words and Ideas Count: Write, Rewrite, and . . . “If I had more time I would have written you a shorter letter.” These words, from one the greatest Roman rhetoricians, Marcus Tullius Cicero, are all about making your words and You Can Write a Great Paper! Dr. Leininger’s Writing Guidelines Page 3 of 5 ideas count. Powerful prose and argumentation results from the hard work of thinking, writing, rethinking, rewriting, and careful editing. First, think through the issues to be addressed from multiple angles and put all of your thoughts on paper. Next, select the most powerful ideas, organize them clearly, and express them succinctly. Your rough drafts should always be longer than the final, edited paper. If you do not have more than enough material to fill the minimum length, you simply have not done the assignment adequately. Come see me if you need help. Do not attempt to make a shorter paper appear longer than it really is (or vice versa). For example, do not use a font larger or smaller than the 12 point Times font in this handout, leave blank lines between paragraphs (except before a heading), expand the margins beyond (or contract them below) one-inch, or stretch out the identifying material at the start (single space name, date, and class). Message: I have crafted my arguments and words with care so that they will make for a worthwhile reading experience. 9. “Show Rather than Tell.” Whenever possible, paint a concrete picture to show the reader what you are trying to “tell” him or her. For example, when presenting the arguments of another author, avoid simply summarizing (as in a book report). Instead, use your own examples, analogies, and words to illustrate and explain these arguments (as if you were explaining them to your roommate). Digest, take apart, reconstruct, and “re-present” the author’s arguments in a new and illuminating way that clarifies the argument for the reader and demonstrates your grasp of these arguments. In sum, “distill the essence” of the argument. For most writers, it helps to a) summarize the main arguments on scratch paper, b) identify the key themes and connections, and then c) “re-present” the argument in a new way that simplifies and/or clarifies it. Message: I understand the ideas well enough to illuminate them in a new way. 10. Don’t “Quote and Run.” Don’t commit the literary equivalent of a “hit and run” automobile accident! First, use a quotation only when the author’s exact words are more effective than any paraphrase could be. Second, explain and comment on the quotation used. Do not use a quotation without any explanation. Rather, show how you interpret the quotation. Message: Here is how I interpret and employ the author’s words in my argument. 11. Use the Active Voice and Strong Verbs. Use active voice rather than passive voice as much as possible and replace forms of the verb “to be” (such as “is,” and “has been said.”) with dynamic verbs. For example, change “The meeting was run by Joe” or “Joe was the director of the meeting” to “Joe directed the meeting.” Message: I write with a powerful dynamism that can move the reader. 12. Use an Appendix for a Summary. Do not place a summary of stories, films, or cases in body of paper. Instead attach an appendix with this information and cite your appendix when you refer to it (for example, “See Appendix 1, “The Good Samaritan,” paragraph #2”). Give each appendix a title. Message: I maximize my use of the body of my paper for thoughtful analysis rather than reporting information. 13. Conclusion: “Re-collecting” Your Argument. Bring together the different parts of your argument by indicating how they establish your thesis. If one accepts your arguments, then what follows? Why does your conclusion matter? Message: Here is how it all comes together and why it matters. You Can Write a Great Paper! Dr. Leininger’s Writing Guidelines Page 4 of 5 III. Demonstrating Strong Scholarship 14. Follow an Accepted Manual of Writing Style Except as Indicated Herein. Papers must be double-spaced (except that identifying material at the beginning, abstracts, and appendixes should be single-spaced) and follow an accepted manual of writing style except as noted in this handout. The preferred manual is the one used in Freshman Seminars at Regis University: Diana Hacker. A Writer’s Reference. 5th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003. This is available at the Writing Center. Message: I have followed standards of writing that are well established in scholarly communities. 15. How These Writing Guidelines Modify Accepted Manuals of Writing Style. These writing guidelines modify accepted manuals of style by, for example, requiring the use of abstracts, headings, paragraph numbers for electronic citations, and headers listing “Page 1 of 6” on each page. You should follow these writing guidelines whenever they conflict with an accepted manual of style. Message: I have followed the criteria that will be used in grading this paper. 16. Use of the Writing Center by all students is strongly encouraged. Bring this handout and a draft of your paper to your appointment with the Writing Center and attach the draft marked up by the Writing Center with the name of the consultant and items addressed at the back of your paper. Message: I care enough about this paper to consult with persons trained to help improve the writing of others. 17. Cite Page Numbers for all Sources and List Works Cited. Use any well-accepted citation style so long as you also provide page numbers or paragraph numbers (e.g., for a church document or a website) for all citations. If you are citing a webpage you need to indicate as precisely as is reasonable where to find this text, e.g., “Section II: The Life of St. Ignatius, paragraph 3.” (Note: this means adding this information to APA format and to MLA and APA electronic citations.) Whenever words or ideas are drawn from other sources and/or are not your own (e.g., quotations or paraphrases), you must cite your source in a way that shows the reader exactly where to find the words or idea in the text. At the end of your work, provide a list of all sources that you drew upon in writing your paper, i.e., “Works Cited” (MLA) or “References” (APA). If you read a book but decided not to draw upon its ideas in your paper you should not cite it. The instructor may check papers against an online service to confirm that it is entirely the work of the student. Message: I show integrity in my scholarship by telling you precisely where you can check my sources. 18. Use Reliable Scholarly Websites. When citing a website document provide a) name of author and institutional affiliation or scholarly credentials and b) paragraph number so that the reader can easily find the exact location (this means that you must count the paragraphs in the document). Do not use a website source as an authority unless you can cite the name of the author, his/her position, and institutional affiliation. When there is no better source available, you may make limited use of a website provided that your argument does not depend upon the reliability of this website and you have made its level of reliability clear to the reader. For example, you may simply want to show that Neo-Nazi websites continue to post hateful racial messages. Message: I draw upon reliable sources. 19. Headers at Upper Right Corner of Each Page. In the upper right header of each page list "Page x of y" (x = page number; y = total pages). In Microsoft Word, drag down the You Can Write a Great Paper! Dr. Leininger’s Writing Guidelines Page 5 of 5 “View” menu to “Header and Footer,” and click this, tab to the right side, type “Page” then click the icon with the # symbol for page number, type “of,” then click the ++ icon for total number of pages. Message: As in any good scholarship, I provide a precise way for others to cite my ideas and know if pages are missing. 20. Proofread with Care. Don’t expect your reader to care when you don’t demonstrate care. Being human often involves making errors. However, as more and more errors accumulate, the reader asks “Why should I read this if the author hasn’t even read it?” Failure to proofread carefully sends an unavoidable message to your reader that you don’t care enough about what you write to bother reading it. Because it can be difficult to catch your own errors, ask someone else to proofread your final draft. Message: I formulated and reviewed my argument with great care so that it will deserve your careful consideration. 21. Turn in Papers on Time or Ask for Extension At Least One Week in Advance. Late papers are marked down 1/3 of a letter grade during each 24 hours. Message: This is not a last minute effort to throw something together. I care enough about this paper to plan ahead to allow adequate time for a deep learning experience and a first-rate piece of scholarship. IV. Learning from Your Mistakes 22. Rewrites will be accepted no later than one week after papers were returned in class. (This deadline applies irrespective of whether or not you were present at class. You may arrange for another student to pick up your graded paper or to notify you that papers may be picked up in L32 in the basket marked “Graded Papers: Dr. Leininger”). Rewrites require a) a marked up draft from the Writing Center (along with the name of the person who helped you and on what issues) b) a redlined version that shows what changes were made from the first version that you submitted (use either Microsoft Word's redlining function or track changes function—the Writing Center can help you with this--OR simply mark with a yellow highlighter all words that remain unchanged from the original draft), and c) the original paper with my comments and grade attached at the back. Rewrites are the most effective way to improve writing. Do not submit a rewrite unless you have substantially changed your paper and/or grammar. If the Writing Center does not have any appointments available within one week, you will need to find someone else who is a good writer and who will generate a marked up draft designed to improve the paper. You will also need to complete steps b) and c) above. Message: I care enough to learn how to improve my paper by consulting with an editor and I have the integrity to show you exactly what I have and what I have not changed from the original paper. Abbreviations used in paper comments SS = Poor or awkward sentence structure (and often incorrect grammar) AWK = awkward construction AV = use active voice rather than passive voice WC = problematic or awkward word choice SP = incorrect spelling