Rural market access and nutritional outcomes in farm households William A. Masters

advertisement

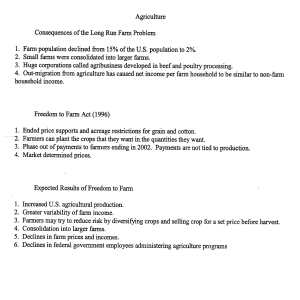

Rural market access and nutritional outcomes in farm households William A. Masters http://sites.tufts.edu/willmasters Amelia F. Darrouzet-Nardi http://sites.tufts.edu/ameliadarrouzetnardi Friedman School of Nutrition, Tufts University Joint A4NH/ISPC workshop on agriculture-nutrition linkages 22-23 September 2014 Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study How do rural markets influence nutrition outcomes in farm households? 1. Could improve or worsen nutrition, by various direct channels a) Household income, wealth and purchasing power b) Time allocation especially for women and children c) Relative cost of access to safe and nutritious foods 2. Could alter the ag-nutrition relationship, by effect modifiers a) Separates decision-making between farm and household b) Alters resilience and consumption smoothing 3. Here we add to the long and old literature on #1 and introduce new work on #2b 4. Will present empirical results then implications and start with a hypothesized causal model Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study A causal model of farm household decision-making Rural markets give households additional options, allowing them to overcome diminishing returns in working their own land Other employment (allows sale of labor to buy food) Qty. of nutritious foods (kg/yr) Rural food markets (allows sale of other goods to buy food) Qty. of nutritious foods (kg/yr) Consumption Consumption Production In self-sufficiency, production =consumption Production Once farmers are actively trading, production decisions are “separable” from consumption choices, linked only through purchasing power That same separability applies whether households are buying or selling, and allows consumption smoothing over time Qty. of farm household’s labor time (hrs/yr) Qty. of farm household’s other goods (kg/yr) Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Empirical identification of causal effects is difficult • Market access tends to be closely correlated with productivity and purchasing power, but relationship may not be causal – Markets may arise and grow where people can use them – People who can use them may move towards markets • Here, we report on two ways to identify potentially causal links between rural market access and farm household nutrition – Globally, do subnational administrative regions with an earlier history of urbanization have healthier maternal and child heights and weights? – Within DRC, do farm households located closer to rural towns have more resilience against seasonal shocks to child heights and weights? • Both studies construct natural experiments, using time lags and spatial variation in risk exposure to identify effects Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study The global study: Does past urbanization help rural farmers today? Log duration of urbanization around rural farm households 80 (with normal distribution superimposed, N=756 region-year observations, of regions that had reached 25% urbanization by 2000) 40 20 0 number of regions 60 Markets take time to develop, and farmers’ regions vary widely in how long they’ve had access to towns and cities -2 0 2 4 log(years before 2000 that the average cell in a region reached 25% urbanization) (Mean year is 1988, earliest quartile is 1970) Note: Data shown are for 756 subnational regions in 53 countries with DHS surveys, using urbanization data from Motamed, Florax & Masters (2014) 6 Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Regions with earlier urbanization have taller children now Mean HAZ for rural farm children at each level of national income, by timing of urbanization -1.45 -1.5 -1.55 -1.6 Child mean HAZ -1.4 -1.35 (N=1171 observations from 143 DHS surveys in 57 countries with 520 subnational regions; dashed line shows subnational regions that reached 25% urbanization before 1995 6 6.5 7 7.5 8 Log of World Bank GNI at PPP prices 8.5 9 Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Regions with earlier urbanization have heavier children now Mean WHZ for rural farm children at each level of national income, by timing of urbanization -.4 Child mean WHZ -.2 0 (N=1171 observations from 143 DHS surveys in 57 countries with 520 subnational regions; dashed line shows subnational regions that reached 25% urbanization before 1995 -.6 For rural farm children, being in a region with more established towns and cities is associated with a very large weight advantage, and a small significant height advantage 6 6.5 7 7.5 8 Log of World Bank GNI at PPP prices 8.5 9 Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study The DRC study: Does proximity to town confer resilience against seasonal shocks? • At each farm location, the timing of a child’s birth exposes them differently to agroclimatic risk factors for malnutrition and disease • The DRC is distinctive in that households vary widely in distance to towns and also in exposure to seasonal risks – We ask whether birth during and after wet seasons is harmful, • For more remote households with less access to markets and services, • In regions with more seasonal variation in rainfall – Birth timing in “placebo” regions without seasons should have no effect Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Birth timing creates a natural experiment • The “treatment” is having a distinct wet season (if there is one) occur during late pregnancy and early infancy – This is a particularly sensitive time for child development – Wet seasons are a hungry period with poorer diets – Wet seasons facilitate water- and vector-borne disease • Market access may be protective – Households can trade to smooth consumption – Households can access health and other services • We expect no effect of birth timing, and no protection from market access, in regions with uniform rainfall Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Analytical design: Spatial difference-in-difference Household location and child birth timing Region has a distinct wet season? (= farther from the equator) Child was born in or after wet season? (=Jan.-Jun. if lat.<0, Jul.-Dec. otherwise) Household is closer to town? (=closer to major town) Hypothesized effect of birth timing: No (“placebo”) Yes Yes (at risk) No Yes No Yes (protected?) Neg. Yes No No Yes No Yes No None Note: To test our hypothesis that market access protects against seasonality, the identifying assumptions are that birth timing occurs randomly between seasons (tested), and that seasonal risk factors would have been similar in the absence of towns (untestable). Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Market access is measured by travel cost weighted distance to the nearest major town Darker cells (100m2) have better market access. Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Seasons depend on rainfall and temperature equator At the equator, average monthly rainfall fluctuates from 100 to 200 mm, and average monthly temperature fluctuates from 24 to 26 degrees Celsius. Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study “Winter” is a drier period, farther from the equator equator Latitude -6 Away from the equator, there is a drier, colder winter, here May through August. Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study In the other hemisphere, winter is 6 months later Latitude +4 equator Here in the Northern Hemisphere, the drier season occurs from November through February. We split the data into groups by risk exposure.. All Children N=2806 Child status HAZ WAZ WHZ Age (mos.) Sex (% boys) Household Wealth quint. Dist. to town (km) Environment Conflicts Lat. (abs val.) Jan.-June No Seasons N=650 Jan.-June Seasons N=903 July-Dec. No Seasons N=563 July-Dec. Seasons N=690 -1.47 (1.86) -1.51 (2.02) -1.51 (1.75) -1.61 (1.92) -1.26 (1.80) -1.20 (1.38) -1.09 (1.42) -1.34 (1.31) -1.17 (1.46) -1.13 (1.34) -0.38 (1.33) -0.22 (1.39) -0.53 (1.21) -0.24 (1.41) -0.45 (1.31) 29.16 (16.53) 28.81 (16.82) 28.53 (15.80) 29.70 (17.10) 29.88 (16.69) 49.4% 47.8% 49.8% 47.9% 51.4% 2.9 (1.42) 64.8 (52.1) 2.61 (1.25) 70.1 (47.9) 3.02 (1.48) 59.6 (51.9) 31.28 (66.9) 4.31 (2.64) 66.53 (97.82) 1.99 (1.16) 9.29 (19.47) 6.14 (2.01) 2.67 (1.26) 71.6 (45.3) 3.19 (1.51) 60.8 (59.8) 48.57 (84.24) 12.74 (22.99) 1.98 (1.17) 5.99 (2.02) Note: Mean (standard deviation). Jan-June births are actually Jul.-Dec. births if the child was born in the Northern Hemisphere (N=418). Conflicts are total number of incidents between 2001 and 2007 in the respondent’s grid-cell of residence. We see a strong and significant “treatment effect” of household remoteness in areas with seasons. (1) (2) (3) (4) HAZ No Seasons 0.000 0.165** WHZ Seasons 0.002 0.102*** WHZ No Seasons -0.000 -0.010 VARIABLES Conflicts Wealth quintile Units/type Cumulative days Categorical HAZ Seasons 0.005** 0.152** Remote Born Jan.-June Born Jan.-June*Remote Child is male Constant Binary Binary Interaction Binary Constant -0.434** -0.363*** -0.407** -0.192* -0.149 0.338 0.141 0.407* -0.192** 0.043 0.010 -0.0534 -0.144** -0.097 0.520* 0.353 0.297* 0.075 -0.195** 0.490 Observations R-squared Number of regions N R2 N 1,593 0.154 10 1,213 0.155 7 1,593 0.082 10 1,213 0.035 7 Note: Age controls suppressed; Jan-June births are actually Jul.-Dec. births if the child was born in the Northern Hemisphere (N=418); robust pval in parentheses; errors clustered by region (N=11); *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Among our robustness checks, we do placebo tests for desirable outcomes that could not be caused by birth timing No effects and large variances where no effect is expected 1.5 1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 -1.5 HAZ WHZ mother's education (yrs) mother currently working? (binary) mother's father's years lived in size of weight (kg) education (yrs) interview household (# location of people) altitude (m) Note: Data shown are coefficient estimates and 95% confidence intervals for average treatment effects in our preferred specification (Table 5), for our two dependent variables of interest followed by seven placebo variables for which no effect is expected, due to the absence of any plausible mechanism of action. Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Conclusions • From these data, – Globally, farm households in subnational regions with a longer history of urbanization have better nutritional status – Within DRC, farm households that are closer to towns are more protected from seasonal shocks to nutritional status • These results add to the large and diverse literature on farmers’ use of markets – New data will permit many new tests to refine results – But the importance of market access has strong implications for agriculture-nutrition actions Market access and farm household nutrition motivation | the global study | the DRC study Implications for policies and programs • At a given level of household and community resources, facilitating market access can – Raise levels of nutritional status – Improve resilience to shocks • Farm households can use markets in many different ways – Specialization and trade, to overcome diminishing returns on the farm – Consumption smoothing, via separability of production & consumption – Access to public services • Future work may be able to distinguish among uses – But various uses are naturally bundled together in related transactions – And in any case policies and programs to ease market access cannot prescribe what households do, just allow them to do it more easily!