Before you print this note that there are 72 pages. ... someday, but for now beware. Dan

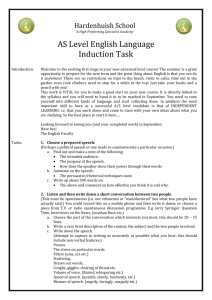

advertisement