“Liberal Education, Collaboration and Sustainable Community Development”

advertisement

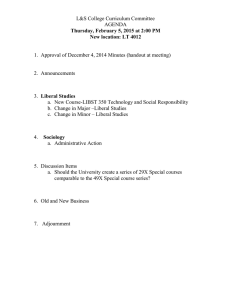

9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 “Liberal Education, Collaboration and Sustainable Community Development” John M. Hasselberg Associate Professor of Management College of Saint Benedict/Saint John’s University 132 Simons Hall, SJU, Collegeville, MN 56321, U.S.A. 320-363-2965 (office) 612-237-0076 (mobile) jhasselberg@csbsju.edu October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 1 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 “Liberal Education, Collaboration and Sustainable Community Development” ABSTRACT Sustainable, organic systems are inherently multifaceted. Tomorrow’s social and economic realities and uncertainties require that to understand ourselves, our organizations, our communities and our disciplines we must appreciate their context and circumstances. Liberal arts colleges emphasize creative, critical and complex thinking and so require study of fine arts, literatures, languages, philosophies, politics, histories, mathematics, and sciences as well as one’s major discipline. Thus interest is growing internationally in crafting university programs modeled on the American multidisciplinary liberal arts/liberal education system. The vision of building Gotland University (HGO), on the island of Gotland, Sweden, as a model liberal education program in Swedish and European higher education began a few years ago. Under the auspices of a Fulbright research/lecturing fellowship this year I will be applying my liberal arts, management and international education experience to work with HGO faculty, students, staff and local community stakeholders to advance this project. HGO is a relatively new school and Gotland an island whose economy and ecosystem are fragile and seasonal and whose people are committed to sustainable development. Thus this is a wonderful laboratory in which to develop a sustainable, useful, inspiring, community engaged liberal educational system. The fine tuning of this model necessarily entails adapting liberal education strategies to their particular location, values, purposes and identity. As it is with liberal arts colleges in the U.S., applying knowledge by engaging the university community with the society and institutions with which they live and work is a priority. Thus a part of our strategy at HGO will be to focus on how the university can be even more synergistically integrated into and collaborative with the October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 2 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 local communities on sustainable economic development strategies and entrepreneurship incentives. In this paper, I will lay out my in-process analyses of this project. Many challenges and successes will emerge from which people and institutions can draw valuable insights and lessons regarding how to more effectively prepare themselves, their people and their communities for a complex and uncertain future. This project is a unique application of collaborative international management strategy research as applied to a young, interdependent university in a small, dynamic and rapidly changing community during times of economic and social transformation. INTRODUCTION For communities, organizations, and societies to be healthy and sustainable citizen members must be empathic self-aware, self-reliant, creative, highly adaptable, locally and globally engaged, free and critical thinking people. Realizing this, Gotland University is transforming itself from the more specialized system, typical of most European higher education programs, to a liberal arts, liberal education system, similar to that of most American private colleges. The purpose of an education in the liberal arts is to educate people to be free, selfdirected yet completely interconnected, and consciously interdependent people. To be a fully engaged member of a family, a community, an organization, or a society one must be able to tell one’s own story and know that it will be heard. Liberal arts education systems create space for individuals to appreciate their own story and those of others. A liberally educated person is able to understand, to create and to tell their own stories. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 3 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 It is when I have been associated with free thinking, liberal education systems that I have felt most free, inspired, creative, self reliant and integrated into my local communities. Thus, I am passionately committed to promoting liberal education. Utilizing my own decades of liberal arts education engagement, I am particularly interested in contributing what I can to working with the people of Gotland University and their related communities to fulfill their visions and dreams for building the first liberal arts education system in Sweden. The world is made up of small communities today all interconnected in a global web. However, it is still true that all politics, all lived experience is very local. To live locally today one must consciously understand and actively experience one’s global connectedness. We must appreciate each local story and, for us to be sustainable as a species, we must learn through benchmarking locally successful practices exemplifying what are the best ways to live. It is my hope that the liberal education transformation through which Gotland University is taking itself will serve as such a template for communities elsewhere in Sweden, Europe, and throughout the world. This paper describes a few essential aspects of liberal education and why it is vitally linked with sustainable community development, interwoven with my own story, and some elements of the processes that I feel may be of value in working with this special community of learners. We can create here a sustainable, integrated, open, and inspiring community wherein each and every member can thrive individually and together. LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION? Why liberal arts education? “The ones who tell the story define the culture.”i October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 4 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Words are metaphors. We use them always with the implication that an image, a feeling, an experience is fully congruent with what we are saying. It always and never is. Each word has its own denotations and connotations, varying from region to region even in English, and certainly when hearing them in English as a second, third, fifth, language. This is the challenge of communication. How to know ourselves and our language well enough to find the words we want to tell our stories in ways others can understand? This is one of the tasks liberal arts education embraces wholeheartedly. So what does “liberal arts education” mean? What are the cultural attributes, boundaries, characteristics, dynamics expressed and implied by saying that someone is “liberally educated”? Does it mean they favor greater intrusion of government into the social sphere? Or does it mean the opposite? Each is true, both are false, depending on what one takes as one’s base for assumptions about how the world works and how one is situated when describing it. When we say ‘liberal’ education, we are not, of course, talking about the dreaded ‘L’ word of recent American political sloganeering, nor are we even referring to the free play of ideas as in traditional liberal political theory. We are borrowing and translating a Greek term eleutherios, ‘free’, a word used most commonly to contrast free people from slaves. It also has connotations of generous, spirited, outspoken, and living the way you want. A ‘liberal education’ means what a free person ought to know as opposed to what a well educated and trusted slave might know. Such a slave might well know a trade, manage a business, run a bank, cut a deal. Athenian slaves did these quite well from time to time, and sometimes did quite well for themselves, too. Some of them developed a craft or a skill, a techne, the Greeks would call it, using the word from which we get ‘technique’ and ‘technology’. …Some slaves possessed valuable skills and could be better managers than their masters. What slaves were not allowed to do, was speak in the assembly, or participate in any other of the rights and duties of a free citizen, the jury system, diplomacy, war. These activities also took skills—technai, but skills of a kind quite different from those looked for in a slave. Our term ‘liberal arts’ is derived directly from a Latin translation of the Greek technai. Since the skills needed to be an effective citizen are so prominent in the Greek October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 5 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 conception of a liberal education, it’s not too much of a stretch to retranslate ‘liberal arts’ as ‘the skills of freedom.’ Since freedom or slavery was so often at stake in citizen decision makings, these were, as well, the skills needed to preserve freedom….Those skills certainly included the ability to speak correctly, persuasively, and cogently— grammar, rhetoric and dialectic as they would be called in the later trivium. The included enough arithmetic to keep an eye on the city’s books, enough geometry to deal with surveying and land issues, and eventually enough astronomy not to be trapped in superstitious dread every time an eclipse appeared. Add harmony to arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy, and you have the quadrivium of medieval times…. In thinking back to the origins of these skills of freedom in the developing democracy of Athens, the central question for the liberal arts today is not: How do we market ourselves? How much vocationalism do we put into the curriculum? Or, how closely can we imitate the research university? It is, what does it take to create a truly open, free society in this strange new world we have entered in recent years? What are the skills of freedom today? ii My own point of view it is one of “both/and” as being central to liberal learning. It is the paradoxes inherent in nature and living cultures, these ironies of systems and the values they purport to embody when doing the exact opposite, that are the fodder, the grist for the liberally designed university system. Students do not come to be trained like dogs. They come to learn how to live more fully, more responsibly, more authentically, more autonomously in a world of vast horizons, complexities and interconnections. Most young people in my experience still want to be taken seriously. Despite their facile sophistications and easy-going cynicisms—more often than not, largely a defense against disappointment—most of them are in fact looking for a meaningful life or listening for a summons. Many of them are self-consciously looking for their own humanity and for a personal answer to Diogenes’ question. If we treat them respectfully and without cynicism, as people interested in the good, the true, and the beautiful, and if we read books with them in search of the true, the good, and the beautiful, they invariably rise to the occasion, vindicating our trust in their possibilities. And they more than repay our efforts by contributing to our quest their own remarkable insights and discoveries.iii More than ever, young people are living in a world where myth and reality are often inseparable, where nature and society follow opposing yet entirely congruent rules, where what people say and what they do seems to have no relationship with one another whatsoever. When October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 6 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 so much of they encounter is mediated by someone or some interest or another, it is hard to not become distrustful, cynical as they struggle to find the solid foundations crucial to living wholly, authentically, in community. PROCESS IS OUTCOME? How do we enable these young people to find themselves and create their destinies? How do we best facilitate their progression through a preparatory experience like life in the university, still a part of life, of course, yet somehow in a gap, on a plane of its own? How do we ensure that it is of both immediate and continuing vitality for them? What precepts ought we as “educators” (who isn’t?) best adhere to when crafting and designing these systems that will shape future generations of students and thus the worlds they will live in? How we design our conversations with them, and the structures within which their dialectical inquiries evolve, must necessarily and appreciatively categorize what they see as possible, as plausible, as necessary for them to know and to do to be fully human, fully alive citizens. It is in the questions we ask, how we ask them and what we ask about. It is in what we choose to emphasize that we communicate how we see the world, how we see the arrival of this future for which they are trying to prepare. To do so with integrity ourselves, we must be most mindful of how the past has evolved, how the visions of the future derived from it frame alternatives and drive choices today. We must be mindful of how these are all grounded in a mystical dance, a vastly intriguing interplay between questions derived from the various, usually themselves too narrowly circumscribed, arts, sciences, humanities, social sciences. How does one best characterize the relationship between inspiration and research? Which is more important, abduction, induction, or deduction? How does one integrate analysis with empathy? October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 7 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 What are the economics of political systems and the forms of violence implicit in each of them? Who gets helped and who gets harmed by each and every decision we make as directors, workers, citizens? And when do we know which is which and who is who? What is the dance between rules and consequences? What are the meta-ethical natures of the words and processes and systems we use? What ought we say and do? What do we actually do vis-à-vis what we think we say and do and what questions emerge inexorably from this tension? How does one think critically and feel intuitively at the same time? What are the relationships between “them”, “us”, and “others”? What does it mean that this language within which I am writing this essay is the only one that universally capitalizes the first person reflexive pronoun—and expresses it as an exceptionally individualistic, one letter, “I”? I do not claim to know the answer to these questions, but I believe that the key to answering is to keep clearly in focus the original understanding of the importance of the skills of freedom….The ability to read texts closely, an alertness to turn of phrase or shift of argument, clear thinking and effective argument in all their forms, good writing, an understanding of how individuals and communities in the past have dealt with practical challenges and moral perplexities, alertness to the ironies of history, the ability to imagine the situation of others and to assess the responses most likely to prove effective are still rare commodities in our society. The greatest problem confronting the liberal arts is not a glut of graduates possessing these qualities, but the difficulties of developing them more fully at every stage of education.iv Critical thinking is thinking that doesn’t accept a priori assumptions. This kind of thinking is not very popular, despite all of the rhetoric surrounding it today as a necessary tool of human educational development and evolution. Cornelius Castoriadis argued that thinking and strict monotheism are mutually exclusive.v Why? Because strict monotheism always results in the same “it is god’s will” answer to every question. Thus, what’s the point of even asking any? Yet for far too many people, such reassurance seems necessary. “People feel real psychological discomfort—psychologists call it ‘cognitive dissonance’—when confronted with views that October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 8 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 contradict their own. They can avoid this discomfort by ignoring contradictory views, and this alone brings like-minded bloggers together…Humans share another psychological habit, too—a strong tendency to adopt, even if unconsciously, the attitudes of those with whom they interact. We even copy other people’s behavior patterns.”vi So, I repeat, critical thinking is often lauded but rarely appreciated. Simply asking “what box?” the next time someone says “think outside of the box” will give one a taste of how much critical thinking may or may not be appreciated. You may well be feeling exactly that way right now as you read this. And to which “that way” I am referring is of course for the reader to reflect upon. The challenges posed by the ambiguities inherent in leadership attributionvii today are daunting. The prices to be paid in society for not minding them as we craft the systems that will truly educate and prepare these generations for a wholly unpredictable future are immense. There must be a concerted effort to move our systems of learning into a more sustainable, resilient and inspiring direction to effectively address these concerns and prepare our children and ourselves to meet them wholeheartedly and with passion and optimism. This is the impetus behind my liberal education enthusiasm and this project. WHY GOTLAND? So why is Gotland University (HGO), Visby, Gotland, Sweden, the right site for my Fulbright fellowship, “Liberal Education, Collaboration and Sustainable Community Development”? First, they are interested. The HGO community has decided that the existing systems through which students are channeled are much too rigid and thus functionally inadequate to prepare them for the complexities, for the interactions between and amongst disciplines, professions, organizations and communities currently or in the future. HGO is intent on creating a niche within Swedish and European higher education by adapting and adopting an October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 9 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 American-style liberal arts/liberal education model. Right now, fall semester 2009, HGO begins its transformation into becoming the first liberal arts college in Sweden. They have embarked over the past five years on building a uniquely designed European liberal education model. Thus there is a solid foundation upon which to build such a system right here, right now. Founded in 1998, HGO is a new university that is very open to finding its own niche within Swedish and European higher education. Thus it is amenable for trying, altering, abandoning and developing new ways of going about fulfilling its educational purposes. As Gotland is an island province with population of fewer than 60,000 people whose capital, Visby, has fewer than 40,000, the citizens of the community are quite conscious of how interdependent with one another they are. All are stakeholders in local community development, whether artistic and cultural, political and economic, social and humanitarian. This necessarily includes attention to how HGO is and can be integrated into the broader fiber of the island society. There is a necessary predisposition towards mutuality of effort, towards integrating the university and its students into the broader community. Thus this makes for an extraordinary laboratory within which to work with a variety of constituents to contribute however I can to facilitating their own community development efforts. HGO is a small, young school struggling to find its place in the world. Building a liberal education niche is a way in which it can best serve its students and communities for the foreseeable, certainly uncertain future. What HGO is embarking on is an inspiring exercise in reframing the direction of higher education in Sweden. Given my liberal arts, management and international education experience, this is an excellent opportunity for me to work with our colleagues on Gotland to help them develop and implement their vision. This initiative requires October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 10 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 that the university ground its students in core liberal arts disciplines and foster skills in writing, speaking and critical thinking. As it is with liberal arts colleges in the U.S., which I have lived, studied and worked within for nearly forty years, connecting and engaging students with the societies, industries and cultures within and with which they will be living and working is a priority. HGO argues that combining a rich liberal arts foundation with a holistic approach to student learning best prepares graduates for the uncertain futures that will mark their lives and careers as local citizens in our globally interconnected societies. “The university student takes a journey into an uncertain future, which is why it means so much to study at a university that cares. At Gotland University, we are dedicated to the bigger picture….In other words, our aim is an all-round education full of the things that make life meaningful and exciting….Our motto is ‘A college for the whole student.’” –Leif Borgert, Gotland University Rektor, 2003-2008viii HOW GOTLAND? At the time of this writing, the summer is soon ending and my process of engagement with Gotland University just beginning. Thus it is wise to keep in mind the academic axiom that “every good teacher has a plan, no good teacher stays with their plan”. This paradox is characteristic of teaching, research, consulting, and, especially for a liberally educated person, to life. I expect to deliver several lectures and to do qualitative primary research on how best to go about instituting a sustainable liberal education program in this small European university setting. I expect an approximate 50/50 split between the teaching and research activities, with significant overlap between them. I intend to rely primarily on typical methods for gathering information: (1) participation in the setting, (2) direct observation, (3) in depth interviews, and (4) analysis of documents and materials. I will coordinate small group symposia and do personal interviewing with community stakeholders on site at HGO, in and around Visby, as well as in October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 11 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Stockholm and at HGO’s collaborating institution, Uppsala University. I have already developed connections, and have done collaborative work, with members of each of these communities. I intend to structure collaborative workshops to engage in active, appreciative dialogue with members of the faculty, staff and student bodies of HGO and the Visby, Gotland community to canvass them on their understanding of, interests in and visions for liberal education at HGO. There has been a loss of industrial jobs on Gotland over the past years, leaving the island heavily dependent on tourism and agriculture. The island has committed to being fully energy sustainable by 2025. What we will be doing together at HGO will emphasize focusing on how the university can be even more synergistically integrated into and collaborative with the local communities on sustainable environmental and economic development strategies and entrepreneurship incentives. Methodologically I will also be utilizing the “Appreciative Inquiry” process. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) was developed by David Cooperrider and Suresh Srivastva in the 1980s. The approach is based on the premise that ‘organizations change in the direction in which they inquire.’ So an organization which inquires into problems will keep finding problems but an organization which attempts to appreciate what is best in itself will discover more and more that which is good. It can then use these discoveries to build a new future where the best becomes more common. Cooperrider and Srivastva contrast the commonplace notion that, “organizing is a problem to be solved” with the appreciative proposition that, “organizing is a miracle to be embraced”. Inquiry into organizational life, they say, should have four characteristics. It should be appreciative, applicable, provocative and collaborative.ix October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 12 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a strength-based, capacity building approach to transforming human systems toward a shared image of their most positive potential by first discovering the very best in their shared experience. It is not about implementing a change to get somewhere; it is about changing…convening, conversing, and relating with each another in order to tap into the natural capacity for cooperation and change that is in every system. At its core, AI is an invitation for members of a system to enhance the generative capacity of dialogue and to attend to the ways that our conversations, particularly our metaphors and stories, facilitate action that support member’s highest values and potential. An AI effort seeks to create metaphors, stories, and generative conversations that break the hammerlock of the status quo and open up new vistas that further activities in support of the highest human values and aspirations….AI takes seriously the notion that how we live our life is a function of where we put our collective attention—that where we focus our collective attention leads to the choices we consider and act upon. By doing so, it provokes the question: What happens if we turn our attention to what is most valuable, life giving and vibrant in the human system?x Our stories as participants in liberal arts education systems show how liberal education does exactly this. It turns our attention to creation, to the beauties of nature and of art, literature, philosophy, mathematics and the sciences that are life giving, vibrant and the essence of being human and creating humane systems. Thus the integration of process and positive, synergistic outcomes through AI embodies a liberal orientation to organizational development and change. In this process of rethinking the nature of change and changing in human organizations, there are several principlesxi that underlie the AI process. First, is the social constructionistxii point of view that asserts that we create the world, personally and organizationally, that we call “real” through our words—our conversations, symbols, metaphors, stories. The stories of the people of Gotland will tell the tale of what is their reality, what it is that I will work on with them, for them. How their stories and mine interweave creates yet another story of our work together. Second, the creative, poetic principle emphasizes that we open new horizons of action through how we choose topics of inquiry. Organizations are human inventions, like poetry, that can be made and re-made, created and re-created. Thus whatever we decide to study directs the vision of the world we want to create. This principle underpins my choice to emphasize the October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 13 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 power of liberal learning in addressing our global and local challenges. Third, the process of making inquiries is not only defining the context we experience and the outcomes towards which we are looking but it in and of itself is a process of simultaneous transformation. As we ask questions, so we become transformed and simultaneously transform what we ask about and those whom we ask. We get what we ask for by ever better understanding our own questions is truly evidence of process as outcome. Fourth, it logically follows that what we anticipate for the future logically changes what is existing right now. The economic consumption function theories of both Friedman’s permanent income and Ando and Modigliani’s life cycle hypotheses are based on exactly this approach to the future. The permanent income hypothesis bears a resemblance to the life-cycle hypothesis in that in some sense, in both hypotheses, the individuals must behave as if they have some sense of the future.xiii There is significant body of philosophical support for our regularly looking into a presumed future and living as if were already happening.xiv Fifth, there is a heliotropic effect to posing positive, anticipatory questions. We gravitate towards the warmth of others, towards opportunity, possibility and health. Good will, trust, hope, excitement and caring relationships are crucial to creating sustainable, responsive organizations and are sine qua non for effective implementation of any strategic evolution. Sixth, the narrative principle celebrates the power of stories as a catalyst for change.xv As noted above, those who tell the stories define the culture. All human communities, systems and organizations are stories in progress. All citizens, all community and organization members are co-authoring their particular stories every day. No human event in a system has meaning apart from a story. We rely upon stories to make our lives meaningful to our selves and to one another, to build bonds, to connect and learn with others.xvi Here are some of mine. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 14 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 STORIES As Pablo Picasso noted, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” I started out as a child. Not seemingly unique, as it is the story of everyone, yet completely so as it is mine. I started out as a child of nature, in nature, beloved of and immersed in nature, inspired by the freedom of the lakes and woods, animals and open lands, immersed in a multi-generational bi-cultural farm family in rural Minnesota, USA. My groundings were ironically doctrinaire religious freedom and the open natural structures of the seasons, of flora, fauna and family. Entropy danced with rebirth, incongruity, obliquity, obviousness and ambiguity were naturally embraced through daily life, in the seasons of life, in the ideologies and energies that floated around and about me. Paradox seemed paradoxically natural, thus it underlies and weaves its way through all of my life, my writings, my instincts towards noticing ubiquitous synchronicities and the serendipities. That is what nature teaches when we pay attention to it, appreciating how we are embedded in it and it in us. I started out my academic life as a student in a one-room country school. There, twentyfour children, spanning eight grades, learned together. We each concentrated on their own assignments while ever aware of the next and reminded of the previous stages of learning iterated and reiterated around us each day. So I learned early to learn and that learning was a part of a long, broad and deep process. I learned to know quickly and well what I was supposed to learn so that I could then explore, create, play with the many things around me from which I could learn to my heart’s content. Flex time. Free schools. Open universities. Elements of all of these were present from the beginning. Rudolf Steiner’s Waldorf system emphasizes that their “curriculum is integrated, October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 15 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 inter-disciplinary and artistic. Thus imagination and creativity which are most important for the individual as well as for society are awakened and developed”xvii. It is noteworthy that Steiner’s main philosophical work was entitled “A Philosophy of Freedom” as it is the freedom of human development that underlies both the philosophy of the Waldorf system and my own passion for the liberal arts-based way of life. All of these seeming innovations were the ordinary, day to day occurrences in my one-room country school. During my sixth year, there were eight students in six grades all minded by one teacher. What a joyous experience to learn in such an engaged and attentive milieu as this! But such a system was not sustainable in an industrial society. It was the 1960’s, local agricultural systems were collapsing, commoditization of daily life was proceeding full force under the will of the ideologies of all sides of the Cold War. Americans and Britons were being systematically transformed from citizens into consumers—an exercise that even a cursory reading of the People’s Daily will show that the Chinese Communist Party has learned well from us.xviii Being a consumer is being shackled, enslaved, particularly that most consumption is now financed by uncollateralized credit card debt—the anti-democratic ramifications of which were understood twenty-five hundred years ago by Solon when firming up Athens’ early efforts at democracy.xix Yet consumption beyond daily food, shelter, clothing needs were mostly irrelevant where I was a child in a mostly self-sufficient rural community. Community— whether through the local school or church—and family and doing one’s work to one’s best ability so that one had time for life were the primary values. Consumption, as the word implies, gouges out the soul of every one of these values and of each participant. It is based on an emptiness that only a healthy, whole self can avoid succumbing to, here argued as best enhanced October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 16 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 by a liberal education into the many and varied facets of life with which a healthy person ought be acquainted. And so my country school was closed and I was moved into a consolidated mass education system, a system already showing itself ill-prepared for industrial change and global transformation in manufacturing, much less in educating children for an ever more complex and unforeseeable future. As with the move from the guilds to the industrial era, education as an institution became ever more focused on producing a consistent, homogenized product rather than tutoring individual students. I was boxed, locked and trapped into a system that was meant for socialization into factory routines at a time when factories were closing, family farms disappearing and the complexities and chaos of a world incomprehensible at the highest levels of our societies was reaching through our televisions into our daily lives. It was an incredibly painful segue from the freedom of the first six years of my formal education. From a place where, mindful of what I was expected to learn, I learned whatever I desired learning I was moved to a place where I was forced to focus primarily on learning how to fit within the institutional framework known as middle-school and high-school. If this is what the world of education was to be like, I wanted no part of it. I wanted nothing more to do with being lied to by being institutionalized under the guise of learning. Learning was something I was perfectly capable of doing on my own, thank you very much. My class knew it for they voted me “Most Dissident”. However, my story of learning or education did not end there. A conspiracy by my high-school counselor and an admissions officer at Gustavus Adolphus College, St. Peter, MN can be thanked. My counselor was correct in intuiting that I was not interested in further institutionalization masquerading as education, however he strongly October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 17 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 felt that a liberal arts education was the antidote to my malaise. Thus, I was blessed with entering the world of the liberal arts college. At his prompting, the admissions officer, called me several times to nudge me to apply to Gustavus. On the fifth call I agreed to do so and in the spring of 1970 found myself on campus registering for fall semester classes. My visit to Gustavus is still remembered to this day by the director of admissions at that time as the only barefoot and suspender jeans-wearing prospect. It was 1970 in America after all. At Gustavus, I remained this creative non-conformist I had been in high school. Although I did chose not to follow anything like a standard four-year plan at Gustavus, my life was transformed by the wise embodiment of the College’s system of its own liberal approach to education. Throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s I adopted a variety of roles in association with Gustavus, roles that were always tolerated, often embraced. I studied and practiced theatre, and sampled a vast array of other courses, regardless of discipline, from math to Latin. I worked while studying, doing project management, becoming a Minnesota Master Gardner, counseling student residents and, upon return following graduate school, teaching ethics and economics. Although not typical of very many students’ experiences, Gustavus was typical in that it provided the space for its students to learn and create and explore as worked best for them. At the same time also guiding us through a series of foundational multi-disciplinary and experiential courses and programs to ensure both a broadening and deepening of our understandings and skills. As one who has crafted such systems in other liberal arts colleges, I find this balance to have been most inspiring to me in supporting a fundamental orientation towards assuming possibility rather than constraint. This is central to my own passionate advocacy for liberal education as optimal preparation for an endless variety of life pursuits. As I reflect on the life in that community I find it fascinating that in true inspirational “educare” fashion I was always October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 18 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 given the benefit of the doubt in whatever activities I pursued, attempted to develop expertise in, or simply found curious and intriguing to learn more about. Thus the paradox towards which this project of my future stories is focused: pedagogies still focus too much on assessing and quantifying, on constraining and channeling and socializing. Educators then wonder at their growing irrelevance to a rapidly evolving constituency when it is these very pedagogies that we have endured that have stunted and blunted our learning skills. Have we forgotten our etymologies? The Romans considered educating to be synonymous with drawing knowledge out of somebody or leading them out of regular thinking.xx Being channeled into boxes that we are then expected to think outside of is at best an amusing irony and at worst a totalitarian nightmare and certainly not conducive to promoting a free, sustainably engaged citizenry. To truly make our communities, our world society, truly sustainable, we must open our systems to whole-being, multi-faceted learning from wherever possible. Learning is the most fundamental of instincts, else none of us would have survived, much less be envisioning building sustainable communities. We know how to educate: “e-ducare”, a drawing through and out from, not a stuffing into, boxing, packaging. It is through real liberal learning that such free and open curiosity can best be nourished. In order for students to understand themselves and their milieu, they must appreciate the questions that surround them, be encouraged to ask them, and be gently guided towards how they can ever better learn to clarify them and answer them themselves. This is abundantly possible in today’s extraordinarily interconnected, networked, instantaneously accessible universe of information. It is also a danger, of course, in that as T.S. Eliot asked: “Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” As we look at October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 19 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 standard definitions of these words we find that the word “act” does not occur until we reach “wisdom”. Information is a resource—an organized set of data, knowledge evidence of an understanding of this resource. However it is through action wherein we are able to ascertain the presence or absence of wisdom. Without action, be it, as Emerson emphasized, creating a garden, writing a poem, building a company or designing a better mousetrap, it is not plausible to know whether information has been adequately and usefully absorbed by the student we all must always be. A vision without action is merely a hallucination. It's essential to distinguish between generating tons of detailed information and creating unique knowledge. Brute force computer analysis of all possible shelf arrangements of only 15 containers of, let's say, anti-acids yields a total of one trillion three hundred billion plus alternatives. Rearrangement of an assortment of 30,000 items, as in a supermarket, yields astronomical figures like 1 followed by 280 zeros! Brute force won't do! That's why we must combine data knowledge with a big dose of human talent: creativity, imagination and uniqueness of thought. Such people are hard to find. Greatly talented individuals are often difficult, disobedient, discordant, disputing and disagreeable.xxi And this is a challenge for many educators who feel a need to control outcomes. When process is the outcome you don’t always get what or who you want to work with. That’s the irony of democracy, of freedom and of liberal education. Liberal education is a process that in of itself is the outcome, a process of inspiring the self-creation of a whole person and a whole people—a necessary prerequisite for sustainable human systems at any level of sophistication. WHOLE PEOPLE CREATING SUSTAINABLE WHOLENESS? Pluralistic democracies, in order to be sustainable, require that everyone’s story be tellable and told, that each citizen have a voice and be listened to. Many cultures emphasize the spiraling upwards from individual to family to society of virtuous, holistic living. Such is the case with community development processes at the local level spiraling out to the global level. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 20 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 A liberally educated person understands this. They appreciate that not only must one understand and be able to articulate their own story but one must appreciate and listen to the stories of others, that there are an infinite number of stories in this world and that each of them has merit to the teller in creating viable and healthy personal identity and relationships. This does not mean that storytelling is the only process through which communities develop. It does mean that without effective and inclusive ways of telling our personal stories, identifying personal meaningfulness and having structures in place to ensure access and inclusion of all constituencies, communities won’t develop, won’t evolve as effectively and authentically as they could. They may or may not survive, but they certainly won’t thrive. And it is to thrive for which we strive. Just to be sustained is insufficient for the human spirit to reach its full sense of fulfillment and to make the kind of contribution to the communities within which we each find ourselves. This is the soul of liberal learning. We cannot dictate precisely what must be learned to best prepare our students for a most uncertain future. We can design systems that allow a great deal of simultaneous loose-tight controls on what we are doing to enable them to become what it is that they are capable of. And that is the point, the ongoing paradox of education at all levels, but particularly so at the university level. What are the heteronomous systems through which we ask students to crawl, walk, dance and fly that will best prepare them for a complex world within which they are expected to be autonomously responsible. How can we best enable them learn how to understand and wisely enact their own destinies while fully appreciating the milieu, the circumstances over which they may have little if any control but within which they will live their lives as citizens, lovers, workers, creators and re-creators? October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 21 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 As we pursue these questions, a few contextual points come to mind that merit inclusion. Is there not a bit of irony in being an American leading a discussion about the relevance of liberal arts education today in Cambridge, when it and its sister university, Oxford, where the phenomenon was initially honed and from whence it migrated to the young United States? First, as with so many cultural phenomena, whether it be systems or languages, both the maintenance of and the improvements to them may often be found in the immigrant cultures. Such has been the case with liberal arts education. However a second look shows today a gradual withering and chipping away at the soul of liberal education in America by the lords of assessment, through myopic marketization, and an via obsession with quantifying outcomes—if not all life. Curiously, and most personally inspiring to me, whilst this deterioration is occurring in my homeland, there is a resurgence of interest in liberal arts/liberal education in Europe.xxii More broadly what is happening in our new millennium is that The American Dream is far too centered on personal material advancement and too little concerned with the broader human welfare to be relevant in a world of increasing risk, diversity, and interdependence….A new European dream is being born…that promises to bring humanity to a global consciousness befitting an increasingly interconnected and globalizing society. The European Dream emphasizes community relationships over individual autonomy, cultural diversity over assimilation, quality of life over the accumulation of wealth, sustainable development over unlimited material growth, deep play over unrelenting toil, universal human rights and the rights of nature over property rights, and global cooperation over the unilateral exercise of power.xxiii Rifkin highlights cycles of time and place with which a thoughtfully crafted liberal education program must grapple. How does one conceive higher education in the twenty-first century in such a way that effectively avoids the perils of the past modernist and post-modernist ossifications while engaging students in ways that well prepare them for life and work in a complex, interdependent global village? This can be done through required multi and crossOctober 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 22 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 disciplinary study, interactive and integrative thought and practice, field application of theory through community involvement activities, program flexibility and adaptability, global awareness and international involvement, systematic engagement of theory and application, and an openness to and understanding of how students’ academic pathways evolve and change as do they themselves. In today’s intensely globally interconnected network of individuals and systems, organizations, societies and cultures, a liberal education blending the creative, multidisciplinary and critical human understandings of the past and present is a necessary prerequisite for anyone intending on treading an economically, socially and culturally sustainable pathway. The effectiveness of liberal education hinges on several points, most prominently an emphasis on educating the whole person for a wholly unpredictable but yet always manageable if one is prepared world. Others, as ways of achieving this ”whole person” status include coupling disciplinary expertise with developing contextual appreciation for one’s own discipline.. Richard Florida has thought and written much about creativity, community development, and our future possibilities. He emphasizes that the university must be at the center of any societally sustainable, holistic economic, cultural, social and technological development in our age. This is a fundamental intention of the people affiliated with Gotland University and central to my vision of what liberal education can contribute to local communities everywhere. Our findings suggest that the role of the university goes far beyond the “engine of innovation” perspective. Universities contribute much more than simply pumping out commercial technology or generating startup companies. In fact, we believe that the university’s role in the first T, technology, while important, has been overemphasized to date, and that experts and policymakers have somewhat neglected the university’s even more powerful roles in the two other Ts—in generating, attracting and mobilizing talent and in establishing a tolerant social climate. In short, the university comprises a potential October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 23 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 – and, in some places, actual– creative hub that sits at the center of regional development. It is a catalyst for stimulating the spillover of technology, talent, and tolerance into the community….In order to be an effective contributor to regional creativity, innovation and economic growth, the university must be integrated into the region’s broader creative ecosystem. On their own, there is only a limited amount that universities can do. In this sense, universities are necessary but insufficient conditions for regional innovation and growth. To be successful and prosperous, regions need absorptive capacity—the ability to absorb the science, innovation, and technologies that universities create. Universities and regions need to work together to build greater connective tissue across all 3Ts of economic development. The regions and universities that are able to simultaneously bolster their capabilities in technology, talent and tolerance will realize considerable advantage in generating innovations, attracting and retaining talent, and in creating sustained prosperity and rising living standards for their people.xxiv It is an age where old religious belief-oriented systems that evolved into the rationalism of the industrial through informational ages are reaching necessarily towards a new emphasis on empathy as the integrating factor amongst all of these forces.xxv Tolerance and empathy are the sine qua non for developing sustainably healthy communities. They require liberality, experience and exposure. They require local and global experience. In fact, it may well be that international exchange is itself a synecdoche for liberal arts education.xxvi So, how does one design such a system? Isn’t there an inherent paradox in even trying to do so? Yes. Of course there is! And that is again the point. If one is to simultaneously engage in developing liberal education systems and sustainable community development exercises—one and the same, I argue—then there is an inherent paradox in the exercise. Bring them in to send them out. Make them learn systems that they can improvise upon. Create processes that show work to no longer be work. If I enjoy what I am doing, is it work? What qualifies as work? As play? As creation? As re-creation? October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 24 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 SOME CONCLUSIONS? This project is a uniquely collaborative application of education policy, organizational development and international management strategy in a small, interdependent university community. It is an exciting example of the vitality of management as a discipline within liberal arts educational institutions and in an internationally interconnected milieu. As a proven method for encouraging well-rounded, insightful, creative and self-reliant students, building a successful liberal education program at HGO will be directly beneficial for the people of HGO, Visby, Gotland, and a model for the Swedish education system and for Sweden’s sustainability goals. When I chaired our faculty at the College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University in 2004 2006, we both restructured our committee governance system and embarked on designing a new Common Curriculum. Thus I was of necessity intimately involved in the policy and implementation priority struggles that are always the hallmark of such a process. Power and systems are always locked in a Gordian dance. The paradox of how to build heteronymous systems to develop students’ autonomy will always be with us. This collaborative celebration that I am privileged to partake in with the members of the HGO community is an extraordinary opportunity to build such systems and develop and implement such strategies. Yet we must always keep in mind that when real synergy occurs not just the whole is greater than the sum of the parts but the whole, the outcome, is both greater than and unpredicted by the sum of the parts.xxvii My nearly forty years in liberal arts education includes over twenty years teaching in the discipline of management, and twelve years crafting and leading numerous international education programs. Chairing our Joint Faculty Assembly and my Management Department October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 25 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 during our Common Curriculum development and committee realignment processes from 2004 to 2007 has enhanced my ability to find amicable common ground between oft competing forces and groups in the university. As Lecturer in the Masters in Liberal Studies program at the University of Minnesota I can appreciate how liberal learning fits within the great research university traditions. As a management expert working within the liberal arts traditions, I know that we can develop appropriate systems and strategies to fulfill this vision. As former departmental chair, I know that management is inherently about the synergistic blending of theory and practice as we work in an infinite variety of organizations to improve our lives and the lives of those around us. The godfather of modern management, Peter Drucker, drove home this point when he selected his essay “Management As Social Function and Liberal Art” as the opening essay in his last collection of the best of his life’s work. He also emphasized that most great changes and innovations which alter the trajectories of industries and societies come from the outside. Thus it is imperative for people in organizations to appreciate the longer waves of change, the interactions amongst fields and disciplines and cultures and technologies.xxviii In our dynamic world of today there is an evolutionary process that seems to be emerging that is calling into question nearly all of the mythical and ideological preconceptions that underlie the modernist and post-modernist, post-industrial, post-post agrarian systems embodying ossified forms of thought. Boundaries are no longer what they were or were thought to be. Movement of ideas, images, thoughts, people, resources is instantaneous and global. This requires a new way of thinking about what it means to be fully human, fully alive, and may well be even driving a new human consciousness model. The children of today, our students of today October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 26 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 and tomorrow, presume a level of human and informational integratedness, of global interconnectivity, of interactivity, of relationship possibilities that simply were not conceivable, much less presumed, by any earlier generations. Business today is more about relationships, sharing and forming alliances than about living with a zero-sum-game mindset. As the principles of Appreciative Inquiry emphasize, we must assume abundance to not be trapped into obsessively and unsustainably compensating for perceived deficits that are actually only deficits in our thinking. If one does expect that we as a species, like all other species, evolve, then a fundamental question must be: how so? Under what influences? Towards what directions? Through what processes? Most catalyzed by what? Who is shifting the most? Where is the shift most pronounced? How does this evolution integrate our nature/culture relationships? Are there discrete boundaries here, there or anywhere? If not, what do we define and how do we do so? Where does art become science become philosophy become psychology become management become dance, become…? To the fundamental question with which we are dealing today, how does one set up a system of education to effectively and efficiently prepare students to be the kind of holistic citizens, fully human, fully aware and ready for this evolutionary process as it accelerates? Liberally, I would offer. No friend of humanity should trade the accumulated wisdom about human nature and human flourishing for some half-cocked promise to produce a superior human being or human society, never mind a post-human future, before he has taken the trouble to look deeply, with all the help he can get, into the matter of our humanity—what it is, why it matters, and how we can be all that we can be….. The search for our humanity, always necessary yet never more urgent, is best illuminated by the treasured works of the humanities, read in the company of open minds and youthful hearts, together seeking wisdom about how to live a worthy human life. To October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 27 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 keep this lantern lit, to keep alive this quest: Is there a more important calling for those of us who would practice the humanities, with or without a license?xxix The magic that occurs in through liberal arts education is not predictable and cannot be controlled. It’s about trusting the process to inspire outcomes, not only to predict them nor to count them. It is about process, not just about outcomes assessment or training. Humans must be helped to open up and unblock to see how they can do things creatively themselves, to learn how they can best learn and continue to learn. I conclude this process with the words one of the twentieth-century’s great artists of change: Each second we live is a new and unique moment of the universe, a moment that will never be again. And what do we teach our children? We teach them that two and two make four, and that Paris is the capital of France. When will we also teach them what they are? We should say to each of them: Do you know what you are? You are a marvel. You are unique. In all the years that have passed there has never been another child like you. Your legs, your arms, your clever fingers, the way you move. You m ay become a Shakespeare, a Michelangelo, a Beethoven. You have the capacity for anything. Yes, you are a marvel. And when you grow up, can you then harm another who is, like you, a marvel? You must work, we must all work, to make the world worthy of its children.xxx i Walsh, D. National Institute on Media and the Family organizational theme. [ available at http://www.mediafamily.org ] ii Connor, W.R., (2000) Liberal Arts Education in the Twenty-First Century, Kenan Center Quality Assurance Conference in Chapel Hill, NC, last accessed on August 8, 2009 [ available at http://www.aale.org/pdf/connor.pdf ] iii Kass, L. (2009) Looking for an Honest Man: Reflections of an Unlicensed Humanist. Jefferson Lecture of the National Council for the Humanities/National Endowment for the Humanities, last accessed August 8, 2009. [ available at http://www.neh.gov/whoweare/Kass/Lecture.html ] iv Connor. Op cit. Curtis, D.A., ed. (1997) The Castoriadis Reader. Oxford: Basil Blackwell vi Buchanan, M. (2007) Our Lives as Atoms: On the Physical Patterns that Govern Our World: A Nation Divided, last accessed August 8, 2009. [ available at http://buchanan.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/04/30/were-not-as-disagreeableas-we-seem/ ] vii Pfeffer, J. (1977) The Ambiguity of Leadership. The Academy of Management Review, 2(1), 104-112 v October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 28 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 viii Borgert, L (2008) A University for the Whole Student, last accessed August 8, 2009. [ available at http://mainweb.hgo.se/adm/liberaleducation.nsf/dokument/A0784C2A66CA4B78C1257439003F1A64!OpenDocu ment ] ix Seel, R. (2008). Appreciative Inquiry, last accessed August 8, 2009. [available at http://www.newparadigm.co.uk/Appreciative.htm ] x Barrett, F. J., & Fry, R.E. (2005) Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Approach to Building Cooperative Capacity. Chagrin Falls, OH: Taos Institute Publications xi Ibid xii Sarbin, T. (ed). (1986). Narrative Psychology: The Storied Nature of Human Relationships. New York: Praeger xiii The consumption function, last accessed August 8, 2009 [ available at http://www.theshortrun.com/classroom/doctrines/consumption.html ] xiv Heidegger, M. (1927) Being and Time. New York: Harper and Row xv Sarbin. Op cit. xvi Barrett, Op cit. xvii What is Waldorf Education?, last accessed August 8, 2009 [available at http://www.waldorfschule.info/en/waldorf-education/what-is-waldorf-education/index.html ] xviii Curtis, A. (2002) The Century of the Self. London: BBC Plutarch (1960). The Rise and Fall of Athens: Nine Greek Lives. New York: Penguin Classics xx RIneberg, G. (2008) Word Power: Education, last accessed August 8, 2009 [ available at http://www.babeled.com/2008/11/27/word-power-education/ ] xxi Kami, M. J. (2000) The Exponential Society: A Manifesto to Executives, last accessed August 8, 2009. [ available at http://www.mikekami.com/files/Exponential%20Society%202000.pdf ] xxii Vide the 2007 birth of the European Colleges of Liberal Arts and Sciences (ECOLAS) consortium building on the priorities ascribed in the European Union’s Bologna Declaration and ensuing Process xxiii Rifkin, J. (2004) The European Dream: How Europe’s Vision of the Future Is Quietly Eclipsing the American Dream. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin Group xix xxiv Florida, R., & Gates, G., & Knutson, B., & Stolarick, K. (2006). The University and the Creative Economy, last accessed August 8, 2009. [ available at http://creativeclass.com/rfcgdb/articles/University_andthe_Creative_Economy.pdf ] xxv Rifkin. Op cit. Richardson, S. (2007) Study Abroad as Synecdoche. Headwaters, 24, 66-81 xxvii Fuller, R. B., (1975). Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking. New York: Macmillan xxviii Drucker, P. F. (2001). The Essential Peter Drucker. New York: HarperCollins xxix Kass. Op cit. xxx Picasso, P. ThinkExist Quotations, last accessed August 10, 2009 [available at http://thinkexist.com/quotation/every_child_is_an_artist-the_problem_is_how_to/143237.html ] xxvi October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 29