Smoothing, Conservative Smoothing, And Truth-telling: The Effect Of The Pressure To Report Target Earnings On The Earnings Management Strategy And The Likelihood Of A Restatement

advertisement

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

SMOOTHING, CONSERVATIVE SMOOTHING,

AND TRUTH-TELLING:

THE EFFECT OF THE PRESSURE TO REPORT TARGET

EARNINGS ON THE EARNINGS MANAGEMENT STRATEGY AND

THE LIKELIHOOD OF A RESTATEMENT

Hila Bracha Yaari

Tel-Aviv University

And

Varda (Lewinstein) Yaari*

Morgan State University

Tel: 443-885-3967

July 2007

.

We grateful to Pete Dadalt, Masako Darrough, and Hila Yaari for valuable comments and

discussions. The paper has benefited from the comments of the participants of the

CAAA, Quebec, June 3, 2005, and especially those of the discussant, Alfred Wagenhofer,

and the moderator, Mary McNally, and to the participants of AAA meeting, SanFrancisco, August 2005, and especially those of the discussant, Bjorn Jorgensen.

Key words: earnings management, smoothing, repeated principal-agent contract,

restatement

Department of Accounting and Finance, Earl G. Graves School of Business and Management, 1700 E. Cold

Spring Lane, Baltimore, MD, 21251. Tel: 001-443-8853445, Fax 001-301-6544670. E-mail:

alexgum21@hotmail.com

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

1

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

Smoothing, Conservative Smoothing, and truth-telling:

The effect of the pressure to report target earnings on the

earnings management strategy and the likelihood of a

restatement

ABSTRACT

This analytical study offers an insight into why the largest accounting scandals

and meltdowns occur in the United States, which is renowned for having the most

developed financial accounting system and firms with the lowest level of managed

earnings. We postulate that the answer lies in the demand for beating targets, where

targets are set for a variety of reasons, such as public debt (since debt covenants specify a

minimum accounting performance) and market expectations. We show that without the

demand to meet targets, the optimal reporting strategy is smoothing: the report overstates

(understates) low (high) outcomes. When there is demand to beat a target report, the

earnings management strategy is conservative: instead of overstating low earnings, the

firm either "takes a bath" or subtracts a downward bias from a truth-telling report. We

also show that the firm combines a low level of discretionary accruals with a restatement,

because a restatement de facto allows the firm to report the same dollar performance

twice: in the past, when it overstated performance, and then again when the past is

corrected and earnings are boosted at present.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

2

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

1. INTRODUCTION

The largest accounting scandals and meltdowns have happened in the United States. In a

study of 919 restatements between 1997 and 2002, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO)

stated: "[W]e found that the unadjusted and market-adjusted immediate losses in the market

capitalization of restating companies approximated $100 billion and $96 billion, respectively”

(GAO 2003 release GAO-03-395R). Coffee 2003, p. 5, reports that "approximately 10% of all

publicly listed U.S. companies restated their financial statements at least once between 1997 and

June 2002 and the annual rate of financial restatements soared during the latter half of the

1990s."

On the one hand, these facts come as no surprise, because public U.S. firms manage earnings

away from the truth. Over 97% of the respondents in a survey of financial officers by Graham,

Harvey, and Rajgopal 2005 admit to preferring "smoothing."1 If a firm overstates earnings long

enough, accruals will reverse and the truth will catch up with it, making the firm restate previous

reports.

On the other hand, these facts are a puzzle, since the U.S. system is known for its welldeveloped financial system, with checks on pernicious earnings management. Dechow and

Schrand 2004, p.62 comment: "A question that naturally arises in a discussion of earnings

management is how companies are able to get away with it. Citations of the U.S. securities

markets as the best regulated, most liquid, most efficient markets in the world are too numerous

to mention" (emphasis added). Furthermore, on the global level, Leuz, Nanda, and Wysocki

2003 find that U.S. firms have the lowest earnings management score (the aggregate of (1)

smoothness of earnings relative to volatility of cash flows, (2) the correlation between cash flows

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

3

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

and accruals, (3) a discretionary accruals measure, and (4) loss avoidance). In sum, what is

unique to earnings management by U.S. firms such that they exhibit the lowest level of earnings

management concurrently with some of the largest accounting scandals?

Our explanation is based on the demand to beat target earnings numbers. The firm has to

deliver a target accounting earnings performance, and when it does not, an accounting scandal in

the wake of restatement might take place. Targets can arise for a variety of reasons: Firms do not

wish to disappoint analysts, so about 40% of public firms meet or beat the consensus analysts'

forecast (e.g., Bartov, Givoly, and Hayn 2002). Firms also may wish to show stable growth

relative to the same quarter of the previous year (e.g., DeGeorge, Patel, and Zeckhauser 1999;

Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal 2005), avoid losses or earnings decreases (e.g., Burgstahler and

Dichev 1997; DeGeorge, Patel, and Zeckhauser 1999), and report a string of earnings increases,

because they are aware that when the string “breaks,” the price plummets—the “torpedo effect”

(e.g., DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner 1996; Barth, Elliott, and Finn 1999; Kim 2002). Firms

that issue bonds are concerned with reporting earnings that exceed minimum levels, since debt

covenants are based on accounting earnings (Smith and Warner 1979), and unlike private debt,

debt covenants in public debts are not renegotiated (Dichev and Skinner 2002). Firms preparing

for an IPO (Initial Public Offering) whose owners have a long-run perspective may set public

targets for earnings (e.g., Hellman 1999; Hochberg 2003; Wan-Hussin, Nordin, and Ripain

2003).

We examine the reporting strategy of firms that face the challenge of beating a target in

their forthcoming reports, modeling it as a principal-agent game between owners and the

manager. As a benchmark case, we show that in repeated principal-agent relationships, the

optimal strategy without targets is smoothing. That is, the reported earnings overstate low

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

4

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

outcomes and understates high ones. When, however, a firm anticipates beating a target, its

reporting strategy is more conservative, as the firm takes a bath or reports the truth less a bias

when smoothing would prescribe an overstatement. This strategy creates a reserve of reported

earnings in order to beat future targets. To distinguish between this strategy and smoothing, we

refer to it henceforth as conservative smoothing. We show that conservative smoothing is the

equilibrium reporting strategy when the future outcome is uncertain. We next examine

restatements. When a restatement reveals the truth, it can be used as an earnings management

vehicle. Aggressive reporting de facto borrows reported earnings from the future. Restatement

undoes the previous borrowing by correcting the past report and shifting the borrowed reported

earnings to the period in which a restatement is made. That is, suppose that the true earnings in

2003 were $1.80 per share, and the firm increased them through aggressive reporting to $2.00.

Then, in 2004 the firm announces that its 2004 earnings are $1.90 before restatement, but

because it has to restate its 2003 earnings, its post-restatement earnings are actually $2.10 per

share. The firm thus achieves its target of reporting $2.00 and $2.10 in 2003 and 2004,

respectively. Examples of this feature of a restatement abound. Even Enron, in its 8-K filing on

November 8, 2001, announced that it "planned to restate its financial statements for 1997 to 2000

and the first two quarters of 2001 …the expected effects would 'include a reduction to reported

net income of $96 million in 1997, $113 million in 1998, $250 million in 1999, and $132 million

in 2000, increase of $17 million for the first quarter of 2001 and $5 million for the second

quarter…” (Jenkins 2003, p. 8; emphasis added).

Employing the “trembling-hand-perfection” concept of Selten, we show that restate

earnings when they mistakenly were too aggressive, so that on the average, a firm may both

reports conservatively and restate earnings. This result is robust to the case when the firm must

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

5

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

beat targets repeatedly and the present target is not too ambitious. At the same time, meeting

targets repeatedly reduces the scope of hoarding reported earnings to beat future targets.

Our results explain the phenomenon of huge restatements by some U.S. firms when all

firms are characterized by a low level of earnings management. Others attempt to explain the

accounting scandals as the result of misbehavior by a few "bad apples" (Demski 2002). 2

Alternatively, Coffee 2003 claims that euphoria in the capital market drove firms to meet

expectations by inflating earnings:

Despite this earlier preference for income-smoothing, by the end of the 1990s,

these same firms were robbing future periods for earnings that could be

recognized immediately. In short, “income smoothing” gave way to more

predatory behavior. Interestingly, restatements involving revenue recognition

produced disproportionately large losses. (Coffee 2003, p. 23)

Yet when all firms manage earnings, all apples are rotten, and if all firms rob future

earnings, why do just 10% restate earnings? Our study identifies conditions under which the

same reporting strategy can yield low accruals for some firms and restatements for others.

In addition, although researchers are aware that firms "take a bath" and establish “cookiejar reserves" (Levitt 1998), empirical research tends to associate earnings management with high

levels of accruals (Beneish 1997). For example, Hochberg 2003 contends that IPO firms that are

supervised by venture capitalists engage less in earnings management because their discretionary

accruals are lower. We, however, offer a different interpretation. These firms, which are

characterized by long-term relationships between venture capitalists and the firm, engage in

conservative smoothing in anticipation of the need to deliver performance in the future.3

Finally, we analyze restatement as an earnings management strategy. To a large extent, a

restatement is viewed as "a moment of truth," as it exposes prior unobservable earnings

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

6

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

management activity (see, e.g., Marquardt and Wiedman 2002, and the citations therein). Yet it

is also an earnings management vehicle, because the firm knows that if worst comes to worst, it

can admit to previous aggressive reporting and therefore can report performance twice, once

when it is "borrowed" to manage earnings and then again upon a restatement.

The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 presents the model. Sections 3 and 4 analyze

the optimal reporting strategy and the probability of a restatement, respectively. A summary and

conclusions are given in Section 5. Proofs are available upon request.

2. THE MODEL

We study the firm as a two-period, principal-agent contract between the owners—the

principal—and the manager—the agent.4 In each period, the firm generates economic earnings,

xt, which are observed by the manager alone, xt Xt=[xt, xt ] t=1,2. The economic earnings,

referred to also as the outcome, are determined jointly by the unobservable periodic effort of the

manager, at, at [ a, a ] , which is chosen at the beginning of each period, and nature.

The assumption that the manager alone observes the outcome implies that at the end of

the first period he alone knows x1, and at the end of period 2 he alone knows x1 and x2. The

owners only observe the yearly accounting reports, m1 and m2. We assume that at the end of the

second period, the total outcome, y, is observable. Hence, the total accumulated accounting

earnings, m1+m2, must equal the total economic earnings, y, y≡ x1+x2.5 Therefore, m2 is uniquely

determined by the accumulated outcome, y, and the previous report, m1, as follows:

m2 ≡ y m1.6

(1)

Equation (1) implies that the owners infer the accumulated outcome, y, by the end of

period 2. The first-period report thus is a vehicle to divide the report of firm's value, y¸ between

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

7

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

the two periods. This feature is supported by our assumption, similar to that of Demski and

Frimor (1999), that the manager commits to stay with the firm for the full duration of the

contract, and that the owners commit to the manager's employment for the two periods.7

Because the contract must be based on mutually observable variables, the manager's

incentives contract is based on the reports, m1 and m2. At the beginning of the first period, the

owners contract with the manager and design his payment schedules, S,

S {S1(m1), S2(m1,m2)}, and the accounting policy, M. The accounting policy determines the set

of admissible reports, m1, {m1} M. Both the owners and the manager know that the firm can

manage earnings by either inflating or deflating them.8

We assume that the reporting technology allows the manager the flexibility to overstate

or understate the first-period outcome. Hence, designing both compensation and the reporting

policy might yield a plethora of contract/reporting policies, all yielding the same payoff. To

illustrate, if the contract is S=0.2m when the manager reports the truth, the contract S=0.1m with

100% overstatement (m=2x) is equivalent. The common remedy to this multiplicity problem is

to invoke the revelation principle, which would let us restrict the analysis to incentivecompatible truth-telling equilibria (Ronen and Ronen 2003). In our setting, however, the

revelation principle does not apply, because target beating renders truth-elicitation prohibitively

costly.

The owners derive utility over the series of earnings, xtSt. Their payoff in the second

period is conditional on whether the firm's report exceeds a target report, L. The target report

represents a potentially traumatic event, since reporting less than L has value-decreasing

consequences. We assume that the target exceeds the minimum second-period outcome, L > x1,

so that if the second-period outcome is too low and insufficient reported earnings are reserved

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

8

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

from period 1, the firm may fail to meet the target. We treat L as an exogenous variable that is

determined by the relationships between the firm and its constituency; its determination is

beyond the scope of this paper. Endogenous determination of L requires admitting a third player,

but this added complexity does not affect results qualitatively so long as L exceeds the minimum

second-period outcome. Since a lower target has no teeth, this requirement seems quite mild.

Denote the owners' piecewise von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function over the series

of reported earnings by V. The owners derive ex post piecewise utility of

tV(xtSt) – g(L– m2)

if m2 L,

tV(xtSt)

if m2 > L.

If the firm beats the target, the owners' payoff is a strictly increasing function of their

residual share of earnings, but if the firm does not, the owners lose utility, g, which is a function

of the gap between the target and the second-period report, Lm2. We make the standard

assumption that V is a strictly increasing concave function, V > 0, V > 0. We make the

following assumptions on g: (i) g is a positive function; i.e., m2 L, g>0. This assumption

guarantees that not beating a target is value-decreasing for the owners. (ii) The loss function is

increasing in the gap between the target and the second-period report; i.e., g=

g

>0.

(L m2 )

This assumption implies that the greater the gap between report and the target, the higher the

loss.9 (iii) Just missing the target is traumatic; i.e., g + (0) . This mathematical assumption

reflects the psychological reality of counterfactual reasoning (Roese and Olson [1995]),

whereby, for example, people are known to experience much more pain when they miss an

airplane by two minutes than when they miss it by six hours.10 (iv) To ensure that the utility loss

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

9

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

from missing a target does not overwhelm the owners' utility, we assume that

G(0) 0, where G= g(z )dz . An example of a function that fulfils the four conditions is g(Lm2)

=

1

.

L m2

The manager’s objective function is to maximize the expected indirect utility over the

stream of future incomes, E[U(St)|a1,a2], net of disutility over effort, W(at), t=1,2, where

U > 0, U < 0, W > 0, W > 0. The manager is risk-averse, effort-averse with an increasing

marginal disutility over effort. We also assume that W(a ) 0 and W(a ) . This assumption

guarantees that the first-order conditions of the manager’s objective function with respect to

effort hold as strict equalities; i.e., the solution is interior. As is common in the principal-agent

literature, we assume that if the manager is indifferent between different effort levels, he chooses

the highest one to please the owners. The manager is willing to participate in the contract when it

guarantees him his reservation utility, U0, obtainable at an alternative job.

We assume that x1 and x2 are independent random variables with prior distribution

functions of f(x1|a1) and f(x2|a1,a2)

and corresponding CDF,

F(x1|a1) and F(x2|a1,a2),

respectively. That is, f(x1,x2|a1,a2)= f(x1|a1)*f(x2|a1,a2). To reflect the fact that some decisions

are investment decisions with repercussions that extend beyond the period in which they are

made, we let the second-period outcome depend on first- and second-period actions.11 These

functions are common knowledge between the owners and the manager. We also make the

standard technical assumptions:

(i)

All functions are twice continuously differentiable (expect for g at zero).

(ii)

The supports of the distribution functions are independent of effort.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

10

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

(iii)

The Maximum Likelihood Ratio Condition (MLRC) holds in each period:

f a ( x1 a1 )

1

f ( x1 a1 )

(iv)

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

and

f a ( x2 a1 , a2 )

t

f ( x1 a1 , a2 )

increase in x1 and x2, respectively.

The manager's utility is concave in the report.

Condition (i) is a regularity condition. Condition (ii) states that effort cannot be inferred

from the observed reports (Holmstrom 1979). Hence, the contract must provide the manager

with incentives to exert effort. By condition (iii), the greater the effort, the higher the expected

outcome. This condition is well-established in the principal-agent literature, because it is crucial

to the conflict of interests between the principal and the agent. The work-averse agent prefers to

work less, and the principal prefers him to work more, because, by the MLRC, higher effort

increases the expected value of the firm. Condition (iv) guarantees that the first-order conditions

used to characterize the equilibrium below are necessary and sufficient to derive the optimal

reporting strategy, the contract, and the probability of a restatement. Without this condition, if the

concavity assumption is not met, the Kuhn-Tucker conditions with respect to the report, m1, are

neither necessary nor sufficient (Chiang 1984), nor do the owners have a well-behaved program

in convex programming (Luenberger 1969). Note, however, that because the manager's utility is

a strictly concave function, this condition does not rule out a convex compensation schedule.

The only condition is that technology and the preferences of the owners and the manager do not

yield contracts that are too convex.

3. THE EQUILIBRIUM

3.1. The Derivation of the Equilibrium

We solve the Nash equilibrium of this setting backwards. We analyze the manager’s

decisions first and then substitute them into the owners' program.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

11

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

3.1. The Manager

The manager makes three decisions: two on actions, a1 and a2, and one on the first-period

report, m1. Since there is no new information between the choice of the first-period message and

the choice of the second-period effort, we assume that he chooses both simultaneously.

At the end of the first period, after observing the first-period outcome, the manager

makes his choices by solving the following program:

x1 , max U( S1 (m1 )) U(S2 ( y m1 ) f ( x2 a1 , a2 )dx2 W(a2 )

m1 , a2

s.t. {m1} M, and a2 [ a, a ].

We specify the reporting policy of the owner as indicating a report mˆ 1 ( x1 ) . M and are

the Lagrange multiplier of the constraint that is dictated by the accounting policy and the

Lagrangian of this program, respectively. The first-order-conditions are

0

M

m1:

0

m1

0

if m1 x1

if x1 m1 x1

if m1 x1

,

(3)

M

where

= U( S1 (m1 )) S1 U(S2 ( y m1 ) S2 f ( x2 a1 , a2 )dx2 M .

m1

M : mˆ 1 ( x1 ) m1 =0.

(4)

a2: U( S2 ( y m1 )) f a2 ( x2 a1 , a2 )dx2 W(a2 ) 0.

(5)

Unless the manager’s choice coincides with the message dictated by the owners, the

optimal report equates the marginal benefit over compensation of both periods with respect to the

message. The optimal message satisfies two demands: the demand for consumption smoothing,

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

12

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

U1 EU 2 , where "E" denotes an expectations operator, and the demand for an increase in

wealth, S1 ES2 . To see the difference between the two, suppose that S1=0.7m1 and S2=0.8m2.

Then, without the demand for consumption smoothing, the manager is better off reporting

everything in period 2, m1=x1, m2=y. (More examples are given below.)

The second-period effort is chosen for its effect on the second-period report. The

manager chooses effort by equating the marginal benefit due to increased monetary payment

with the marginal disutility over effort. Recall that our assumptions on disutility over effort

imply an interior solution (Eq. (5) holds as a strict equality).

Definition 1:

(a) "Truth-telling" occurs if the first-period report coincides with the first-period outcome.

That is, m1=x1, and therefore m2=x2.

(b) "Smoothing" occurs if the first-period report overstates low outcomes and understates

high outcomes.

That is, there is a critical value of x1, x1c , such that if

x1 < (>) x1c , then m1 > (<) x1.

(c) "Aggressive reporting" occurs if the first-period report overstates all outcome. That is,

m1 > x1 for all x1.

(d) "Taking a bath" occurs if the firm reports the minimum first-period outcome, x1 ,

m1= x1 , even when the actual outcome is higher, x1 > m1= x1.

Definition 1 is consistent with the standard definitions of earnings management strategies

(Scott 1997).

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

13

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

Proposition 1:

If M = 0, then the manager's reporting strategy is smoothing. If M >0, the manager reports

the message that is dictated by the owners; i.e., m1 ( x1 ) = mˆ 1 ( x1 ).

The smoothing result has already been established in the smoothing literature (see Dye

1988; Yaari 1991; Meth 1996; Boylan, and Villadsen 1997; Demski 1998; Sankar and

Subramanyam 2001; Srinidhi, Ronen, and Maindiratta 2001; and others). The fact that m1

allocates the report of aggregate outcome y between the two periods implies that the reporting

strategy can either report all in one period or divide the outcome between the two periods.

Smoothing obtains because the manager prefers to split the reported y between the two periods.

The manager maximizes expected utility by overstating (understating) the first-period message

when the first-period outcome is low (high) and the expected second-period compensation is

higher (lower), borrowing (hoarding) reported outcome from (for) the second period. Such a

reporting strategy maximizes the manager’s utility because the marginal utility over the firstperiod report is a deceasing function of this report. An optimal allocation of a dollar report

between two periods when the marginal payoff is a decreasing function is to split it to even out

the marginal payoff between the two periods.12

If, however, the owners' reporting policy does not enable the manager to smooth

optimally, he will make the report that the owners prefer, because the owners can enforce their

policy by penalizing the manger when the second-period cumulative outcome is inconsistent

with their design.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

14

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

Denote the equilibrium first-period report and second-period effort by *. At the beginning

of the first period, the manager chooses the first-period effort, a1, by solving the following

program:

max

m1 , a2

U(S (m )) f ( x

*

1

1

1

a1 )dx1 U(S2 ( y m1* ) f ( x1 a1 ) f ( x2 a1 , a2* )dx1dx2 W(a1 ) W(a2* )

s.t. a1 [ a, a ].

By our assumption on the disutility over effort, the first-order condition yields

a1:

U(S (m )) fa ( x

1

*

1

1

1

a1 )dx1 U(S 2 ( y m1* )) f a1 ( x1 a1 ) f ( x2 a1 , a2* )dx1dx2 W (a1 ) =0. (6)

The manager chooses effort by equating the marginal benefit due to increased monetary

payment with the marginal disutility over effort.

3.2. The Owners

With “E” denoting the expectations operator, the owners solve the following program

when they design the manager’s compensation:

x1

max

S1 , S2 , m1 , a1 , a2 , m1

x1 x2

V( x

2

EV(S , m1 , m2 L,a1 , a2 )= V( x1 S1 (m1 )) f ( x1 a1 )dx1

x1

S 2 (m2 )) f ( x1 a1 ) f ( x2 a1 , a2 )dx1dx2

x1 x 2

x1 min{L+(m1 x1 ), x 2 }

x1

G(L m2 ) f ( x1 a1 ) f ( x2 a1 , a2 )dx1dx2

x2

s.t.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

15

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

x1

EU(S a1 , a2 ) W(a1 ) EW( a2 ) U( S1 ( m1 )) f ( x1 a1 ) dx1 W( a1 )

x1

x1

x1

x2

U(S2 ( y m1 ))( x2 a1 , a2 )dx2 W(a2 ) f ( x1 a1 )dx1 U 0 .

x2

(IR)

{a1,a2,m1} = argmax EU(S a1 , a2 ) W(a1 ) EW( a2 ) .

(IC)

x1 m1 m1 ,

at [ a , a ], t 1,2

The contract must guarantee the manager his reservation utility level—the (IR)

constraint—and take into account the effect of the compensation schedules on the manager's

choices. That is, the owners are the Stackelberg leader in this principal-agent game, because the

compensation schedules and the reporting policy determine what the manager chooses for effort

in both periods and as the first-period report—the (IC) constraints. Note that the Lagrange

multiplier for a1 (Eq. (7)) is a scalar, but the Lagrange multipliers for the first-period message

and second-period effort are functionals of x1. In our working paper version, we set the Euler

equation of this program (see Gelfand and Fomin 1963) and solve it for the two compensation

schedules. Since this characterization is useful only to establish that the incentives contract is a

pointwise function of performance, a result that is already well-established in the principal-agent

literature, it is omitted here.

Proposition 2:

The owner design an increasing incentive contract.

Proposition 2 conveys the intuitive result that the owners design an incentive contract

that increases in the reported outcome. While this result is quite common in the principal-agent

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

16

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

literature, still it does not extend here because the fact that the manager can manipulate the report

implies that the maximum likelihood ratio that drive this result in the standard game may not

hold in our scenario.

3.2. The Firm’s Reporting Strategy

Proposition 3 presents the equilibrium reporting strategy.

Proposition 3:

Divide the range of outcomes into three regions:

I: x1 X x1 L x2 x1 ;

II: x1 X L x 2 x1 x1 L x 2 m1* ( x1 ) ; and

III: x1 X x1 >L x 2 m1* ( x1 ) .

(a) In equilibrium, the reporting strategy is as follows:

ˆ 1 ( x1 ) x1 . .

In Region I, the firm "takes a bath," m

ˆ 1 ( x1 ) x1 (L x2 ) .

In Region II, the firm reports the truth less a negative bias, m

In Region III, the firm smoothes (as per the manager's preferences).

(b) In regions II and III, the manager and the owners obtain the same payoff as under smoothing

(given the global effect of a piecewise contract on the incentives contract), and the manager is

penalized if the firm fails to beat the target in the second period.

Proposition 3 characterizes the firm’s reporting strategy as a function of L. We divide the

set of outcomes into three regions, depending on the availability of reserved reported first-period

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

17

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

earnings, m1x1, that can be reported in the second period. In Region I this reserve is too low,

because it falls short of Lx2. In regions II and III, x1 is large enough, but in Region II the firstperiod message is too high.

Since the manager prefers smoothing (see Proposition 1), the issue is when to let him do so.

The answer depends on the target. If the first-period outcome is low, the first-period report that

minimizes the likelihood of failing to beat the target is the minimum first-period message; i.e.,

the firm "takes a bath." When, however, the first-period outcome is sufficient to guarantee

beating the target, but a smoothed report might prevent the firm from beating the second-period

target if it overstates the first-period outcome, the owners induce the manager to report the truth

less just enough to guarantee that the firm will beat its targets. For example, suppose that the

target report is 50 and the minimum second-period outcome is 0, the true first-period outcome is

60, and the desirable smoothed report is 120. The maximum report that guarantees beating the

target of 50 is 10, 60-50=10. A higher report might still allow the firm to beat the target, but the

result is not certain. The manager is paid the same as under smoothing (as per Proposition 1),

given the piecewise contract, because the owners can undo the report and pay him the same as

under a smoothed report. The manager follows suit, because if he reports more, the secondperiod outcome might fall short of the target, and he would be penalized. If he reports less, he

deviates from the optimal payment schedule specified under smoothing as per Eq. (3), which is a

utility-decreasing event.

Empirically, smoothing is a well-documented phenomenon (see, e.g., Ronen, and Sadan

1981; Belkaoui and Picur 1984; Bartov 1993; Brown, Ewers, Manson, and Turner 1994; Bhat

1996; Bitner and Dolan 1996; Moyer, Shevlin, and Hunt 1996; Carlson and Bathala 1997;

Defond and Park 1997; Chaney and Lewis 1998; Oyer 1998; Beattie, Anctil, and Chamberlain

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

18

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

1999; Elgers, Pfeiffer, and Porter 2000; Buckmaster 2001; Wan-Hussin and Ripain 2003). As

Levitt 1998 and Turner 2001 have noted, however, firms also engage in creating "cookie jar

reserves" and "taking a bath." Proposition 3 characterizes a smoothing strategy that never

overstates earnings. We label this strategy “conservative smoothing.”

Kirschenheiter and Melumad 2000 identify a reporting strategy of "taking a bath" when

earnings are low and smoothing when earnings are higher, but their explanation differs from

ours. They study a model in which the firm's price is based on expected future performance and

the variability of the outcome. When earnings are low, the motivation to increase the price by

enhancing the report of future earnings dominates the reporting strategy, and the firm forgoes

smoothing and creates instead a "bank" of reported performance by taking a bath. When true

earnings are good news, the firm can afford to increase the price by smoothing out the variability

of earnings. Thus, their smoothing is a means to reduce the information asymmetry between the

firm and the market. The similarity between our studies is that the target creates the demand for

"taking a bath." In our study, however, the demand for smoothing follows from the favorable

effect of letting the manager smooth on the cost of the contract. In addition, we find that there is

demand for an understated report that equals a truth-telling message less a downward bias.

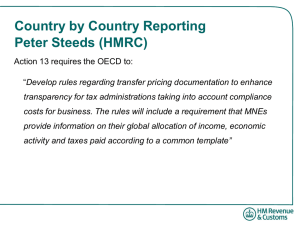

We summarize the analysis with a graph that compares truth-telling, smoothing

(Proposition 1), and smoothing with hoarding of reported earnings (Proposition 3). The distance

between the truth-telling line and the managed earnings measures the earnings management

intensity locally, so that the area between the two measures the intensity of earnings management

as defined in Definition 2 below. The graph is based on L1=40, L2=50, and the slope of

smoothing is 1/2.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

19

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

FIGURE 1: REPORTING STRATEGIES

400

350

Truth-telling (45 degress line)

Smoothing (Proposition 1)

Conservative smoothing (Proposition 3)

FIRST-PERIOD REPORT

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

-50

OUTCOME

We next present the implications of Proposition 3 for earnings management.

Definition 2

The magnitude of earnings management (EM) is the expected deviation of the reported

earnings from the true earnings, EM = ∫(m1x1)dx1.

Our definition captures the intuition behind empirical studies that examine earnings

management by total accruals (e.g., Healy 1985) and the magnitude of discretionary accruals

(e.g., Kline 2000).

If the firm reports the truth for all first-period outcomes, EM=0. Such a

measure allows us to compare the magnitude of earnings management under the different

reporting strategies.

Proposition 4: Control for the effect of target-beating on expected earnings:13

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

20

400

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

(a)

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

The smoothed message of a target-beating firm is lower for each level of

outcome.

(b)

Targets reduce the magnitude of earnings management.

Proposition 4 is a corollary to Propositions 1 and 3.

Conservative reporting reduces the

level of earnings management.

Proposition 4 implies that a low level of discretionary accruals is an indication of earnings

management to beat future targets. Our result contrasts with that of Dutta and Gigler 2002, who

find that the magnitude of earnings management increases in the target, where targets are set by

earnings forecasts (disclosed by the privately informed manager). If earnings are insufficient to

beat the target, the manager resorts to an aggressive earnings management strategy. In our study,

earnings anticipate the target. Hence, targets create demand for building a reserve of reported

earnings.

4. THE PROBABILITY OF A RESTATEMENT

In this section we analyze the connection between targets, a target-beating reporting

strategy, and the probability of a restatement.

Definition 3:

A restatement of earnings occurs when the firm announces at the end of the second

period that the reported first-period earnings were misstated, m1 ≠x1.

This definition captures the essence of restatement, whereby firms rewrite history (Wu

2002). Some restatements are initiated by auditors (WorldCom), some by the company (Enron),

and some by an investigation by the SEC (Fannie Mae, AIG). The correction of previous reports

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

21

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

usually has a favorable effect on earnings in the period of restatement, because, for example,

revenues were prematurely recognized and current earnings should be boosted.

We make the following assumption that the restatement reveals the truth.

Assumptions:

(A1)

When a firm restates earnings, the firm augments earnings in period 2 by the

difference between the reported and the actual first-period earnings, m1x1.

(A2)

Restatement is costly.

This assumption indicates that a restatement can "undo" previous earnings management,

so that the total true historical earnings effectively set a limit on the size of the restatement. In

our two-period example, this assumption implies that the firm reports the truth in the second

period, because by Eq. (1), m2 without a restatement is x1+x2m1, so that with a restatement, m2=

x2. We are unaware of any study that has clarified the connection between a restatement and the

truth. Because we observe examples of repeated restatements, it seems that firms are reluctant to

reduce past earnings, and they are forced to restate that much because the truth is discovered.

Thus, a restatement has limited usefulness as an earnings management vehicle, since a firm that

inflates earnings in period 1 cannot, through restatement, "take a bath" ex post, beyond the

obvious disadvantage of the costliness of a restatement.

We are aware that in large samples the latter assumption is not innocuous. (see Jones and

Weingram 1997; Coffee 2002; and Marquardt and Wiedman 2002). Wu 2002 and Richardson,

Tuna, and Wu 2004, for example, find abnormal returns of -11% over a three-day window

surrounding the restatement event, and Wu 2002 notes that when restatement involves revenues,

the abnormal return is even lower, -14.4% or less. Restatements reduce the credibility of the

firm's accounting earnings (Wu 2002; Anderson and Yohn 2002) and increase the cost of capital

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

22

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

immediately after restatement (Hribar and Jenkins 2004). We expect that if the cost of a

restatement were considered, then the difference between Proposition 3 and Proposition 4 would

disappear and the firm would choose conservative reporting over smoothing with a restatement.

As we show in the next subsection, however, this conclusion changes when the firm endeavors to

beat targets repeatedly.

4.1. The Firm Beats One Target

Proposition 5

Consider the trembling-hand-perfect equilibrium reporting strategy.

(a)

The level of earnings management (Definition 2) of a target-beating firm is lower

than that of a firm that does not beat targets.

(b)

If a firm trembled in period 1 and reported aggressively, it restates earnings in

period 2 if it allows it to beat the target.

Proposition 5 indicates that the firm now has arsenal of means to beat the target. First by

reporting conservatively, and then, if a mistake was made, by restating earnings. The reason that

a restatement is not desirable as managing earnings is that it is costly.

Proposition 5 also indicates that the finding of low earnings management globally, with big

but a few restatements is a large sample phenomenon, since any single firm that did not tremble

and reported conservatively will not restate earnings. To sharpen this point, observe that there

will be two types of firms: conservative reporters and aggressive reporters who may restate

earnings.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

23

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

4.2. The Firm Beats Targets Repeatedly

In this section, we assume that the firm has to beat a target in both periods. Since

allocating a dollar of reported outcome might involve a trade-off between competing targets, we

make the following assumption:

Assumption: Not beating a target in period 1 entails the same utility loss as not beating a

target in period 2.

This assumption implies that the owners’ utility, when the target in period t is denoted by

Lt, is

t[V(xtSt) – gt(Lt– mt)1t,

where 1t is an indicator function that takes the value of one if mt Lt, and zero otherwise.

Proposition 6:

(a) The reporting strategy when the firm has to beat targets repeatedly varies. If

x1 L1+L2+x2, the firm reports the target. If x1>L1+L2+x2, the firm smoothes. A

restatement is likely if the smoothed message falls in Region II.

(b)

There is a critical level of a target, denoted Lc, such that if L < Lc, the earnings

management level of a firm that beats targets repeatedly is lower than that of a

firm that does not beat targets.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

24

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

Proposition 6 indicates that when a firm has to beat targets repeatedly, the scope of

conservative reporting declines, and we are likely to witness restatements concurrently with a

low level of earnings management. This proposition is interesting because it shows that when the

firm has to choose between beating two targets, beating the earlier target takes precedence over

beating the later one. Since the firm cannot eliminate missing the target in the second period

with some positive probability, it prefers beating the first-period target with certainty and risking

not beating the target in period 2 to missing the target in period 1 for sure but missing the target

in period 2 with a lower probability.

5. SUMMARY

Our study explains why the level of earnings management as measured by the bias

between earnings and report is low in the United States, although the US also sees an avalanche

of restatements and large accounting scandals. We explain this puzzle by the practice of letting

financial reports beat targets that are determined by the interaction of the firm with its

stakeholders. We find that when targets are not in danger of being missed, firms smooth and

thus reduce the variability of earnings. When the target may not be reached, firms either adopt

truth-telling with a downward bias or take a bath. The result then is a reduction in the

magnitude of earnings management. The advantage of biased smoothing is that owners can

replicate the same payoffs as under the desirable equilibrium with smoothing without

compromising beating the target. We find that a restatement can be used as an earnings

management vehicle to eliminate mistakenly aggressive smoothing, which yields a profile of an

average firm reporting conservatively with the occurrence of restatement.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

25

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

REFERENCES

Anctil, R., & Chamberlain, S. (1999). Accounting-driven earnings smoothing. Working paper.

Arya, A.; Glover; J. & Sunder, S. (1998). Earnings management and the revelation principle.

Review of Accounting Studies, 3(1&2), 7-34.

Barth, M.E., & Finn, M. (1999). Market rewards associated with patterns of increasing returns.

Journal of Accounting Research, 37(2), 387-413.

Beattie, V.A, Brown, S., Ewers, D., John B., Manson, S. Thomas, D., & Turner, M. (1994).

Extraordinary items and income smoothing: A positive accounting approach. Journal of

Business Finance and Accounting, 21(6), 791-811.

Belkaoui, A., & Picur, R.D. (1984). The smoothing of income numbers: some empirical

evidence on systematic differences between core and periphery industrial sectors. Journal

of Business Finance and Accounting, 11(4), 527-545.

Beneish, M.D. (2001). Earnings management: a perspective. Managerial Finance, 27 (October),

3-17.

Bhat, V.N. (1996). Banks and income smoothing: an empirical analysis. Applied Financial

Economics, 6, 505-510.

Bitner, C.W., & Dolan, R.C. (1996). Assessing the relationship between income smoothing and

the value of the firm. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 35(1), 16-35.

Border, K.C. (1985). Fixed points theorems with applications to economics and game theory.

Cambridge University Press.

Boylan, R.T., & Villadsen, B. (1997). Contracting and income smoothing in an infinite agency

model. Working paper. Washington University. Olin Working Paper Series OLIN-97-16.

Burgstahler, D., & Dichev, I. (1997). Earnings management to avoid earnings decreases and

losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24(1), 99-126.

Carlson, S.J., and Bathala, C.T. (1997). Ownership differences and firms’ income smoothing

behavior. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 24(2), 179-196.

Chaney, P.K., and Lewis, C.M. (1998). Income smoothing and underperformance in IPO.

Journal of Corporate Finance: Contracting, Governance, and Organization, 4(1),1-29.

Christensen P.O. Demski, J.S., & Frimor, H. (2002). Accounting policies in agencies with moral

hazard and renegotiation. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(4), 1071-1090.

Coffee, J.C. Jr. (2002). Understanding Enron: it's about the gatekeepers, stupid.

http://SSRN.com/abstract=325240.

Coffee, J.C. Jr. (2003). Gatekeeper failure and reform: the challenge of fashioning relevant

reforms. Working paper No.237, Columbia Law School.

DeAngelo, H. DeAngelo, L.E.; & Skinner, D.J. (1996). Reversal of fortune: dividend signaling

and the disappearance of sustained earnings growth. Journal of financial Economics, 40(3),

341-371.

Dechow, P.M; & Dichev, I.D. (2002). The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual

estimation errors. The Accounting Review, 77(Supplement), 35-59.

Dechow, P.M., & Schrand, C. (2004). Earnings quality. Research Foundation of CFA Institute.

Defond, M.L., and Park, C.W. (1997). Smoothing income in anticipation of future earnings.

Journal of Accounting and Economics, 23(2), 115-139.

Degeorge, F., Ding, Y. Jeanjean, T. & Stolowy, H. (2005). Does analyst following curb earnings

management? international evidence. http://ssrn.com/abstract=683921

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

26

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

DeGeorge, F., Patel, J. & Zeckhauser, R. (1999). Earnings management to exceed thresholds.

Journal of Business, 72(1), 1-33.

Dewatripont, M., Rey, R., & Aghion, P. (1994). Renegotiation with unverifiable information.

Econometrica, 62(2), 257-282.

Dichev, I.D., and Skinner, D.J. (2002). Large-sample evidence on the debt covenants hypothesis.

Journal of Accounting Research, 40(4), 1,091-1,134.

Dutta, S., & Gigler, F. (2002). The effect of earnings forecasts on earnings management. Journal

of Accounting Research, 40(3), 631-656.

Elgers, P.T.; Pfeiffer Jr. R.J., & Porter, S.L.. 2000. Anticipatory income smoothing: A

reexamination. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=218648.

Evans, J.H., &Sridhar, S.S. (1996). Multiple contract systems, accrual accounting, and earnings

management. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(1), 45-65.

Fudenberg, D. Holmstrom, B., & Milgrom, P. (1990). Short-term contracts and long-term

agency relationship. Journal of Economic Theory, 51(1), 1-31.

General Accounting Office. (2003). Financial statement restatement database. GAO-03-395R.

Washington, D.C.

Graham, J.R., Harvey, C.R., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate

financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40 (1-3): 3-73.

Gigler, F.B., & Hemmer, T. (2004). On the value of transparency in agencies with renegotiation.

Journal of Accounting Research, 40(5), 871-892.

Hellman, N. (1999). Earnings manipulation: cost of capital versus tax. A commentary.

European Accounting Review, 8(3), 493-497.

Hermalin, B., & Katz, M. (1991). Moral hazard and verifiability: The effects of renegotiation in

agency. Econometrica, 59(6), 1735-1754

Hochberg, Y. (2003). Venture capital and corporate governance in the newly public firm.

http://ssrn.com/abstract=474542.

Hunt, A., Moyer, S.E., & Shevlin, T. (1996). Managing interacting accounting measures to meet

multiple objectives. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 21(3), 339-374.

Jenkins, G.J. The Enron collapse. Prentice-Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Kamien, M., & Schwartz, N. (1981). Dynamic optimization: the calculus of variations and

optimal control in economics and management. North Holland.

Kim, I. (2002). An analysis of the market reward and torpedo effect of firms that consistently

meet expectations. Presented at the European Financial Management and marketing

Association meeting, January. http://ssrn/com/abstract=314381.

Klein, A. (2000). Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management.

Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(3), 375-400.

Lambert, R.A., 2001. Contracting theory for accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economic,

31(1-3), 3-87.

Leuz, C., Nanda, D.J., & Wysocki, P.D. 2003. Earnings management and investor protection: an

intentional comparison. Journal of Financial Economics, 69(3), 505-527.

Levitt, A. (1988). The numbers game. A speech delivered at the NYU Center for Law and

Business.

Luenberger, D.G. (1969). Optimization by vector space methods. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New

York.

Marquardt, C., & Wiedman, C.I. (2002). How are earnings managed? An examination of

specific accruals. Working paper. New York University.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

27

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

Meth, B. (1996). Reduction of outcome variance: optimality and incentives. Contemporary

Accounting Research, 13(1), 309-328.

Roese, N.J. and Olson, J.M. (1995). What might have been: The social psychology of

counterfactual thinking. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc: Mahwah, New Jersey.

Rogerson, W., 1985a. Repeated Moral Hazard. Econometrica: 53(1): 69-76.

Ronen, T.; & Yaari, V.L. (2002). On the tension between full revelation and earnings

management: A reconsideration of the revelation principle. Journal of Accounting, Auditing

& Finance, 17(4), 273-294.

Sankar, M.R., & Subramanyam, K.R. (2001). Reporting discretion and private information

communication through earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(2),365-386.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52,

737-783.

Spiegel M. (1962). Advanced Calculus. Schaum's Outline Series. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Smith C.W. & Warner J. (1979). On financial contracting: An analysis of bond covenants.

Journal of Financial Economics, 7(2), 117-161.

Srinidhi, B., Ronen J., & and Maindiratta, A.J. (2001). Market imperfections as the cause of

accounting income smoothing – The case of differential capital access. Review of

Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 17 (3), 283-300.

Sunder, S. (1997). Theory of accounting and control. Southwest College Publishing: Cincinnati,

OH.

Wan-Hussin, W.N. & Ripain, N. (2003). IPO profit guarantees and income smoothing.

http://ssrn.com/abstract=411380.

Wu, M. (2002). A review of Earnings restatements. Working paper, New York University.

Yaari, V.L. (1991). On hoarding in contract theory. Economics Letters, 35(1), 21-25.

Yaari, V.L. (1993). A taxonomy of disclosure policies. Journal of Economics and Business,

45(5), 361-374.

Notes:

1

Furthermore, the respondents indicate a willingness to sacrifice long-term value in order to

pursue short-run earnings management objectives, by taking actions such as postponing

investment in value-enhancing projects.

2

We do not mention the “poor governance” explanation, because the evidence at hand suggests

that the United States has a better governance structure than other economies (see, e.g., Shleifer

and Vishny 1997).

3

Degeorge et al. 2005 provide international evidence of the effect of the pressure to beat targets

on earnings management.

4

In this study, we analyze finite-horizon games. One of the basic premises in accounting is the

"going concern" assumption, which some researchers translate to mean that the firm has infinite

life. Yet because all transactions tend to have finite life and accruals management is a matter of

allocating the recognition of transactions intertemporally (Dechow and Dichev 2002), it seems

that a repeated, finite-horizon model is better suited to study issues of earnings management with

reversal of accruals.

5

This feature of the model is common in the income-smoothing literature (see, e.g., Truman and

Titman 1988; Boylan and Villadsen 1997) and is based on the accounting principle that prohibits

double counting.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

28

7th Global Conference on Business & Economics

ISBN : 978-0-9742114-9-7

6

As discussed in the introduction, note that the condition that a dollar performance cannot be

reported twice is a basic assumption in double-entry accounting. This assumption is prevalent in

the earnings management literature. There are a couple exceptions: Evans and Sridhar 1996

study the choice of control mechanism when there is an internal demand for earnings

management; they demonstrate that in the absence of resettling, the equilibrium of a repeated

game collapses to the equilibrium of a one-shot game. Sankar and Subramanyam 2000 examine

the value of endowing the manager with discretion over the choice of accounting treatment.

They assume that GAAP reverses discretionary accruals partially. They show that for some

threshold level of reversal, the manager overstates income boundlessly.

7

We assume away renegotiation of the original contract at the end of the first period. The

principal has incentives to ensure that renegotiation does not take place (as proved by

Dewatripont, Rey, and Aghion 1994, since renegotiation tends to reduce the principal’s welfare

(see, e.g., Fudenberg and Tirole 1990; Demski and Frimor 1999;Yim 2001; Christensen, Demski,

and Frimor 2002; Gigler and Hemmer 2004). To the best of our knowledge, only two studies find

that renegotiation is Pareto improvement: Hermalin and Katz 1990 assume that the principal and

the agent obtain non-contractible information after contracting that can yield the first-best

allocation, and Ronen and Yaari 2001 assume that renegotiation has no effect on incentives

because they study a one-shot game wherein the renegotiation takes place after effort has already

been exerted. Neither case is relevant to our framework.

8

It is reasonable that overstatement is different from understatement in terms of costs and

benefits. If a firm understates m1, m1 < x1, the firm accumulates hidden reserves that are

reinvested at an internal rate of return, r, which increases the second-period income by (1+r)(x1m1). If it overstates m1, m1 > x1, the firm either makes cash-increasing accounting changes or

engages in unobservable transactions that reduce the second-period outcome by (1+i)(m1 x1).

Without loss of generality, in what follows, we let r=i=0, which does not affect our results

qualitatively.

9

This assumption is a convenient technicality that allows us to use the generalized mean value

theorem in the proofs below. It can be relaxed without affecting the results.

10

We draw attention to the fact that this assumption represents the fact that the owners have

incentives to take measures that prevent the firm from not beating the target. We personally

sympathize with (iii) because it represents how we felt when less than a point was needed to earn

an A in a course as opposed to how we felt when the gap was larger.

11

For a study that explicitly models effort as investment decisions that affect earnings growth,

consult Gavious, Ronen, and Yaari 2001.

12

To illustrate, suppose that the contract is a linear function with the same marginal reward,

St=a+bmt, t=1,2. Then, if the manager's utility function is U(z)= z , a=0, b=0.01, allocation of

$10,000 between the two periods exceeds the payoff from reporting all in a single period:

2* 50 = 2*7> 100 10 . See also the valuable discussions in Dye 1988 and Yaari 1993.

13

Proposition 4 does not address the incentive effects of target beating. This can be addressed

by adapting the definition of earnings management to control for size effect the way it is done in

empirical research, which usually deflates all variables by lagged assets.

October 13-14, 2007

Rome, Italy

29