Supply Chain Visibility, Supply Chain Integration and Information Sharing – The Antidote for Supply Chain Myopia

advertisement

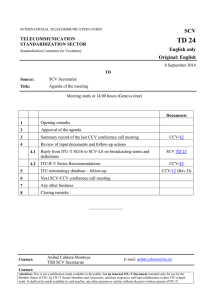

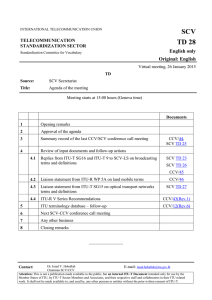

2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Dr. Kumaraguru Mahadevan Adjunct lecturer Sydney Graduate School of Management (SGSM) University of Western Sydney Sydney, Australia Supply Chain Visibility, Supply Chain Integration and Information Sharing – The antidote for Supply Chain Myopia. Purpose: This paper aims to report on the findings of industry based empirical study of supply chain integration, supply chain visibility and information sharing in minimising SC myopia. Design/methodology/approach: The research was taken with the realist tradition. It begins with the research is based on a deductive approach with rigorous and systematic analysis of research material. Findings: The findings confirm that level of supply chain integration, supply chain visibility and information sharing are affected by organization dimensions and a number of situation factors. Research limitations/implications: This research paper is limited to the logistics and manufacturing industries. The use of statistical analysis with only non parametric tests for this research. Practical implications: The work provides some insights for supply chain practitioners Original/value: This paper draws on empirical research. Keywords: Supply chain myopia, Supply chain integration, supply chain visibility and information sharing Paper type: Research Paper July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 1 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Abstract The aim of this paper is to gain insights into the current directions to date taken by academia and practitioners to incorporate SCV (Supply Chain Visibility), and IS (Information Sharing) in organisations through SCI (Supply Chain Integration) if it can reduce supply chain (SC) myopia. This paper presents three key areas of interest to SC practitioners. Firstly, it highlights there is evidence that increasing the level of SCI will reduce SC Myopia. Secondly, the limited research on the management aspects of SCI, IS and SCV that raised three research questions. Thirdly, the investigation of the three research questions will provide academics and practitioners both the static and dynamic position of SCI, IS and SCV. The findings of the study are recommended as antidotes to practitioners to reduce SC myopia Key words: Supply Chain Myopia, Supply Chain Management, Supply Chain Visibility, Supply Chain Integration, Information Sharing. INTRODUCTION In recent times, supply chain management (SCM) has attracted significant interests among researchers, academics, and practitioners. According to Gundlach et al. (2006), Bowersox et al. (2007), Simchi-Levi et al. (2000), Tan et al. (2002) and Speier et al. (2008), SCM has increased in prominence as a field of inquiry and practice with evolving sophistication. The terminology “supply chain management” (SCM) is used frequently in today’s materials management environment are separated into two distinct substructures: physical flow and storage of goods, and information associated with those goods, thus raising the question of SCV (Lewis & Talalayevsky 2004). On the other hand the term “Supply Chain Myopia” or July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 2 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 supply chain “short-sightedness” though not widely discussed in SC literature, although Hertz (2006) in her study discusses about its effects on SCI within a SC and between overlapping SC networks. Further, Hertz (2006) found according to Ludvigsen (2000) SCI would involve IS, common standards, common cultures, joint planning, joint mission and increase in social contract. Whilst literature review does not provide a clear definition of SC myopia Hertz (2006), it may be interpreted as having limited or insufficient knowledge of the products, processes, operations and sales volume of its upstream or downstream SC partners. Hence, it can be argued that SC myopia is linked to SCI, IS and SCV. Further Hertz (2006) stated that increasing SCI will reduce SC myopia and the study itself did not specify the impact of IS and SCV on SC myopia. Moreover, the study did not reveal if SC “short sightedness” implied as the lack of knowledge of products, processes, operations and sales volume between the immediate SC partners, or amongst the SC partners in a SC. On the contrary, there is a wide range of research publications available on SCI, SCV and IS in the context of SCM. However, the available research mainly focuses on areas such as technology/framework development, SC modelling and theory based studies, although limited numbers of researchers have focused on hypothetical studies in areas of SCI and SC performance. Based on these findings, it was observed that research in the areas of SCI, IS and SCV to date mainly focused on technology related, but limited in the arena of management issues relating to SCV, SCI and IS. On the contrary, Chapman et al. (2007), Pearcy & Giunipero (2008), Cagliano et al. (2005), Wong & Wei (2007), Kwon & Suh (2004), Vereecke & Muylee (2006) and Johnson et al. (2007) have carried out investigative studies with some aspects of SCI and SC collaboration but lack in addressing SC myopia. Likewise Clements & O'Loughlin (2007) conceptualised a supply chain myopia model, however, their work was not linked to SCI, IS and SCV. Hence, there is a justification for a July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 3 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 comprehensive literature review to establish the current position of the research focussing on the management aspect of SCI, SCV and IS. LITERATURE REVIEW The literature review is structured into four major areas of investigation which comprises of: state of global SC; emerging SC processes and strategies; current techniques, tools and systems; and current integration practices in industry. Current state of global supply chains The state of SC represents the current issues, developments and emerging trends of SC. Traditionally SCM has been an accepted terminology in manufacturing industries although non-manufacturing groups such as the banking, finance and transport industry are increasingly leveraging the concept. Rajib et al. (2002) found information flow or IS will not be restricted to logistics chain, and simultaneously it is increasingly being used freely between different enterprises with banks, government enterprises and other organisations making a SC very dynamic. Although SC managers are familiar with mantra “supplier’s” suppliers to “customer’s” customers linked by means of SCI Fawcett & Magnan (2002), on the contrary only a few companies are actually engaged in such extensive SCI (Akkermans et al. 1999; Harps & Hansen 2000; Kilpatrick & Factor 2000;Thomas. 1999;Whipple et al. 1999). Therefore, only a few companies have adopted and disseminated formal SCM definitions; and further even fewer have meticulously mapped out their supply chains to gain visibility of their “supplier’s” suppliers or “customer’s” customers in an end to end fashion. Consequently, Fawcett & Magnan (2002) raised legitimate question, “How do companies define and approach SCI?” July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 4 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Whilst a plethora of definitions are available for SCI, the integration approach deployed by organisations is of significance. Integration between organisations is an emerging trend supported by technologies, whilst integration within organisations is in its mature stage (Sandoe et al. 2001). Whilst there has been extensive research publications in the area of SCI within the organisation focusing on ERP systems and business improvement a number of researchers (Wang & Wei,2007; Koh et al. 2006 and Mortensen & Lemoine, 2008) established there is limited work of similar magnitude in the arena of integration between enterprises. These researchers added most of the research focused on technical integration with limited coverage on the management aspects or “softer side” of such as processes, philosophies, strategies and policies. Subsequently, there is a significant level of activity in the spectrum of mergers and takeovers of the transport/storage businesses within the space of LSPs (Logistics Service Providers) Lieb (2005). This industry has an estimated value of USD 76.9 billion according to Bowersox et al. (2007), however the level of academic research related to SCI, IS and SCV was found to be insignificant. In the midst of a growing trend of SCI on one hand, and simultaneous increase in use of LSPs according to Fabbe-Costes et al. (2009) there is limited SCI research that focuses on the role of LSPs and the role LSPs might play in the integration of their client’s SC. Lieb & Bentz (2005) added LSPs today have become collaborative hence advantageous for the big users of these services with a shift in power bases as they become more selective who they do business thus, forcing small and mid-size customers to scramble to find the logistics services they need. Additionally, there is evidence that control of the SC is shifting amongst the SC partners, and further this shift in power bases has been enabled by the application of the Internet (O'Toole & Robinson, 1999). Whilst the research in relation to LSPs indicates a growing trend in SCI among SC partners, on the contrary Fabbe-Costes et al. (2009) found it is still in its infancy. On the other hand, July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 5 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 the term SCV has become a popular buzzword in SC literature Barratt & Oke (2007) and it could be argued that it is possibly a “by-product” of SCI. However, these researchers further added that SCV is viewed as an ill defined, poorly understood concept and assumed if companies across SC have visibility of demand, inventory levels and processes that it will improve organisational performance. On the contrary, Francis (2008) found the term ‘Supply Chain Visibility’ (SCV) to be ubiquitous, nevertheless within the spectrum of emerging trends of SCM other researchers have pointed out its definition is still unclear. There is also evidence that in the absence of supply chain visibility, trading partners have to carve out data from their ERP (enterprise resource planning) or legacy systems (Katunzi 2011). Further, the data is sent to another organisation where it has to be uploaded to other systems prior to the data being shared and evaluated which inevitably results in time loss for end customers and higher costs across the supply chain. Based on Katunzi (2011)’s work it appears that organisations value the importance of SCV. Whilst SCM professionals consistently rank SCV as one of the most important issues confronting them today, Francis (2008) and Anonymous (2009) reinforce this important issue with an investigative study titled as “the smarter SC of the future” that describes SCV as the biggest challenge for Chief SC officers. In contrast, Langley (2002) identified there is limited value in researching on SCV for achieving SC improvement. Whilst SCV reviewed in a standalone position highlighted limited development of the concept between organisations, on the contrary Krishnamurthy (2002) investigated the fundamentals of SC velocity, SC viscosity and further identified (IS) information sharing as a key element for gaining SCV. In order to function in the current competitive times, SC partners need to be more informative about other partners in a SC Wisner et al. (2005), hence the importance of IS. Further Wisner et al. (2005) added, in order to manage the flow of information and materials organisations July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 6 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 will need to share strategic level information at a corporate and business level. In recent times, the benefits of SCI, IS and SCV in the supply chain environment have been noted by many researchers (Priesmeyer et.al.2012; Power 2005; Sandoe et al. 2001; Swaminathan and Tayur 2003; Wisner et al. 2005). These researchers posit that foremost tangible benefit of integration is cost reduction, whilst process integration can also result in better quality. Priesmeyer et al. (2012) found in recent years, business environments have dramatically increased in dynamic complexity, requiring organizations to adapt more quickly and frequently. Currently, organisations share mainly demand information between manufacturers and retailers (Davenport & Brooks,2004). On the contrary, there are many reasons why business enterprises in a SC are unable to gain visibility of demand information and some of the impediments include: lack of communication of demand information throughout the SC Fliedner (2003); lack of trust over complete IS between SC partners Hamilton 1994, Stedman (1998) and Stein (1998); and an unprecedented level of internal and external cooperation is required in order to attain the benefits offered by collaboration McLaren et al. (2002). Emerging SC strategies and processes Some of the emerging trends in SCM in the arena of academic research consists of integration of strategies, ERP 11 and Reverse Logistics (RL) in the context of SCV, IS and SCI. The individual processes in an organisation are needed to activate the various functions that are needed to be supported by strategies which can range from marketing, inventory management, procurement and manufacturing Wollman et al. (1997), Hugos (2006) and Thompson & Strickland (1998). Marketing and manufacturing strategies according to Prabhaker (2001) that behave in a pendulum swing manner, goes from a classical manufacturing phase to a post-industrial phase as they become market driven. Based on these observations Prabhaker (2001) has redefined the way businesses can be managed in which July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 7 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 the traditional marketing and manufacturing disappear with the emergence of a powerful “integrated marketing-manufacturing”. The strategic and operational integration of marketing and manufacturing further supported by the notion that the development and realisation of these two concepts are strongly interdependent Prabhaker (2001). In addition, the theory based strategy-structure-performance paradigm by Speier et al. (2008) was identified to position information integration relative to the nature of relationships within the broader SC strategies a firm employs. However, as firms become increasingly focussed on SCI as strategic goal, the issue of information systems “fit” with overall SC strategy becomes critical (Lee et al. 1999). Similarly, ERP 11 has been viewed as an important concept to industry according to Moller (2005) and until now its research has neither been consistent or conclusive as regards to the content and status of this phenomenon. It is viewed as a “business strategy” with a set of industry or domain specific application that build shareholder value by enabling and optimising enterprise/inter-enterprise collaborative operational and financial processes Bond et al. (2000). Whilst conceptually ERP 11 could support and enable SCV, there is limited research supporting this view. The other areas of interest where SCV and SCI are of relevance is reverse logistics (RL), however its research is limited to process integration mainly discussed by Rogers & TibbenLembke (1998). Simultaneously, Mahadevan & Samaranayake (2006) proposed an integrated SC framework for RL operations incorporating manufacturing processes, bills of materials and scheduling profiles, however the approach taken can only partially address SCV. Current tools, systems and techniques In the current end-to-end SCM environment organisations use a series of techniques, tool and systems to manage and optimise resources ranging from sourcing, procurement, warehousing/distribution, manufacturing and sales. Moreover managing the various stages of July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 8 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 the SC a set different tools, techniques and systems may be used. They may be summarised as follows: tools applied such as CPFR (Collaborative Planning Forecasting and Replenishment) and SC systems; techniques such as SCOR model and Integrated Approach (IA); and systems including ERP and SCM systems. Within the space of a collaborative SC, the future evolution of CPFR will permit an automatic transference of SC partners demand forecasts into vendor production schedules and SC planning applications such as warehousing and inventory control applications of ERP systems Skjoett-Larsen et al. (2003). These researchers further added the next logical step in the development or enhancement of CFPR is the inter-enterprise integration of various ERP systems planning for SC partners. Conceptually such an arrangement could increase the level of SCV across a SC, however, there is limited research supporting that view. In reviewing some of the other techniques that is currently proposed for use in industries, Samaranayake (2005) proposed the Integrated approach (IA) that combines the activities, materials, resources and suppliers involved in a manufacturing operation which forms the basis for development of a SCM framework. Further its main features include the integration of individual components, elimination of interfacing steps between SC partners, representation of relationships and whilst it addresses SCI between organisations the approach does not specify collaborative planning among SC partners hence the limitations in addressing SCV. Within the space of the tools currently applied, the ERP integrates all the business functions within an organization (Shehab et al. 2004; Davenport & Brooks 2004). Consequently the movement towards B2B e-commerce and SCM have forced ERP system providers to reevaluate their models and thereby adopting a shift towards more flexible systems to compensate for the need to adapt to changing business cultures (Tarn et al. 2002). July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 9 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Subsequently, Dwyer (2006) found the SCOR (Supply Chain Operations Reference) model claims to add value to SCV through the addition of standardised metrics. In addition the model operates within a cross functional space provides a SCV solution across the enterprise and companies can benefit from this consolidated knowledge base. Likewise, Haydock (2003) views the SCOR as a cross industry model that decomposes the processes within a SC and provides a best practice view of SC processes further becomes a collaboration tool to improve SC processes between SC partners end to end SC. Although in contrast Haydock (2003), Scalet (2001) and Atkinson (2001) found the application of the SCOR model in SC operations has limited support of SCV, whilst Power (2005) found the SCOR model has failed to interface SC partners. Integration Practices in industry Strategies, tools, processes, systems and techniques collectively enable IS and SCV through SCI across a SC. Consequently, SCI, if inappropriately conceptualised can have a detrimental impact on market responsiveness and value generation capability (Rai & Bush, 2007). In integrating competencies and resources of diverse SC to provide better service to customers, enabling SCI requires a new way of thinking (Stank et al.,2001). Further indentifying six competence areas that top firms deploy to achieve SCI include: customer integration; supplier integration; material and service supplier integration; technology and planning integration; and relationship integration. In addition Rai & Bush (2007) identified innovation in Internet technologies, e-business and process standards, such as Rosetta Net, are challenging assumptions to manage resources across supply chains to create value. Further, these researchers identified five types of SCI configurations: fragmented chains; end to end integrations; modular chains; and web solutions chains. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 10 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 FINDINGS OF LITERATURE REVIEW AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS The terminology SC myopia is not widely discussed in research publications with limited discussions and unclear definitions. However, there is evidence that SC myopia can be minimised through increased SCI between overlapping supply chains, although there is a lack of similar level of discussion of similar effects as a result of SCV and IS. On the other hand, there is a wide spectrum of findings that relate to SCI, SCV and IS in the context of SCM, both in its current environment and its possible future expectations were identified. Both industry practitioners and academics have recognised that businesses are being faced with challenges in which they need to be competitive and having a highly visible SC is one of such an important lifeline to ensure competitiveness is met. However, such a visible SC can only be effective if SC partners are highly integrated and share information with another. On the other hand, whilst cross enterprise integration along SC is increasingly occurring, it is unlikely that all firms will have collaborative supply chains (Bowersox et al.,2007). In reviewing the state of supply chains, it is evident that SCI is not discussed extensively in terms of the current operations in industry, although SCV is frequently debated within the spectrum of the future and emerging trends. Whilst the mergers and takeovers between SC partners could possibly initiate and encourage SCI and IS, researchers have had minimal focus in this area Fabbe-Costes et al. (2009). Equally, researchers have concentrated on organisations’ requirements and directions in terms of SCV, IS and SCI in the future as a result of mergers and takeovers. Hence, the current state of SCI, IS and SCV in practice is somewhat inconclusive leading to the research question: What is the current state of play of SCI, IS and SCV in organisations across a SC? The purpose of this research question (referred to as RQ1) is to identify and position the current standing of SCI, IS and SCV within the broader SC practices in industry and how it impacts on SC myopia. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 11 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Whilst RQ1 aims to position the current standing of SCI, IS and SCV, the desired position on the other hand reflected in the literature review focuses on the required degree of SCI, IS and SCV for increasing collaborative relationships between SC partners. Although there is extensive research publications available on the “hard” or technical aspects of collaborative relationships, there are however limited research material on the “softer” or management issues such as collaborative relationships across supply chains. These collaborative relationships can exist across organisations at various levels and include forecasting, demand planning, supply planning, network planning and distribution resource planning with SC partners. Although collaborative relationships exists at various levels of many functional areas, the main area for discussion in research has been collaborative demand planning among SC partners which has metamorphosised from a simple sales consumption and profitability analysis to a combination of many inputs including sales consumption, profitability analysis, market estimates/knowledge and trends through collaborative relationships. On the other hand, within the spectrum of collaborative SC relationships, collaborative planning forecasting and replenishment (CPFR) is identified as the most recent prolific management initiative that provides collaboration and SCV in a SC (Attaran & Attaran,2007). Further, these researchers concluded CPFR as an enormous potential for reducing the total cost of SC. Skjoett-Larsen et al. (2003), McLaren et al. (2002) and Fliedner (2003) found in the CPFR process demand forecast (sales forecast) is the key information that is exchanged, however there is limited information on whether other operating data/information such as resource capacities (labour, production, storage and distribution capacities) and materials/products are exchanged or shared among SC partners. Thus, it can be argued that demand visibility alone of an organisation is not sufficient as only contributing factor for total SCV across the end to end SC. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 12 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Whilst research has revealed that both industry practitioners and academics have recognised IS across businesses is a vital ingredient for SC excellence, however from a management perspective there is no conclusive evidence on how relationships are best managed in industry across collaborative SC partners. This leads to the research question 2 (RQ2): What degree of SCV, IS and SCV are required by management in strategising and operationalising the desired aspects of SCV, SCI and IS in a collaborative SC? The purpose of RQ2 is to identify and establish what degree of SCV, SCI and IS managers need to address in managing a collaborative relationship (reducing SC myopia) that not only exchanges and make decisions on sales and demand information, and financial transactions but also key operational aspects (production, storage, and distribution) of a SC. They may include, from an operational perspective the ability to influence the planning, control and execution of materials, resources, activities of other SC partners, understanding of operating information of upstream and downstream SC partners. Further, the degree of SCI, SCV and IS required by managers in their collaborative SC may vary between one SC partner to another. Prior to establishing the degree of SCI, IS and SCV required by managers for a collaborative environment for competitive and sustainable SC practices among partners, it is necessary to gain a holistic view of the supporting elements such as processes, strategies, tools, systems, policies and philosophies that play a significant role in strategising and operationalising these practices are discussed next. In the current SC practices, in particular SCI across SC partners, the use of ERP systems and EAI architecture, according to Bowersox et al. (2007) are identified as systems and infrastructure play a crucial role in enabling vital links among SC partners. However, the focus of collaborative relationships among SC partners to date has been firstly in the transactional space in the area of accounting or payment processing for procurement of goods and services. Secondly, collaborative demand planning is based on sales forecasts and the July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 13 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 consumption rate. Furthermore, literature review revealed there is limited research in application of related strategies to manage these collaborative relationships, however Van Laneghem & Vanmaele (2002) proposed a new paradigm for tactical demand chain planning (DCP) within the space of collaborative SC planning, highlighting the necessity to integrate market information into planning techniques that will reduce uncertainty through the use of market information such as lead times, capacities, prices, product demand, and promotions. Moreover, Prabhaker (2001) based on his observations on manufacturing and marketing strategies, found traditional marketing and manufacturing strategies can be merged into a powerful integrated “marketing-manufacturing” strategy. However, successful implementation of such an integrated marketing-manufacturing strategy requires a fundamental rethinking of classical marketing, manufacturing economics and integration of business functions (Prabahker, 2001). Whilst there is fundamental thinking in conjunction with integration of strategies within an organisation, limited evidence of similar research mirrored across a SC. Overall, there is limited research work on these key aspects and/or addressing key issues associated with strategies, processes, tools, philosophies and systems associated with SC practices, in particular integrated systems supporting collaborative SC practices that will provide SC partners an end to end SCV thereby leading to research question 3 (RQ 3): What elements (strategies, philosophies, processes, tools, systems) and frameworks are required by management in operationalising and strategising SCI, SCV and IS in a collaborative environment? The purpose of RQ3 is to identify elements (information systems, tools processes, policies and strategies) that are required to address not only demand planning but also operational planning in a collaborative environment. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 14 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Research methodology In examining the theoretical perspectives supporting SCM, Storey et al. (2006) indicated that there is substantial gap in the theory and practice in the emerging field of SCM, in addition only a few practitioners attempted to prescribe SCM with modern theory. On the other hand, Mentzer et al. (2004) indicated the need for a unified theory of logistics in supporting SCM as researchers have not attempted to develop a theory of the firm that accommodates the role of logistics. Furthermore SCV, SCI and IS are emerging topics in field of SCM which have limited literature on the prescription of modern theory. A deductive reasoning approach is chosen although there are limitations of the theory of the firm accommodating the role of logistics to conclude the RQ’s derived through literature review, data collection through a survey questionnaire and hypothesis testing. The survey questionnaire is based on six constructs comprising of 48 variables of categorical data include the following: organization dimensions; importance of SC operations to an organisation; the current level of SCI, IS and SCV in an organization; understanding of SCI, IS and SCV in an organization; development of a tool for enabling SCI; and strategies in an integrated SC. The variables are further categorized as: “Yes or No”, single response, multiple response, rating (Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7) and open-ended. The survey was conducted internationally, targeting 600 organisations engaged in SCM, concentrating on 5 countries, including Australia, USA, UK, Germany, and China. There were 120 companies targeted in each country, and were chosen with respect to size, based on volume of sales (AUD) broken into the following categories: <50 million; 50 to 250 million; 250 million to 1 billion; and 1 billion to 5 billion. The targeted organisations were further divided into 20 categories by sales for each country. From each category based on the available contact information the surveys were sent to the executive (CEO), senior manager (General Manager/Vice President) and operational manager (Supply Chain Manager). A total of 64 July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 15 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 (10%) responses were received from the 600 survey questionnaires sent out, mainly from large MNC with global operations involved in manufacturing, logistics, 3PL services, retail and distribution. The response rate of 10% is as expected as it is often difficult to get senior managers to participate in surveys of this nature due to their time constraints, and maintaining confidentiality of an organisation’s information. The data analysis is divided into descriptive analysis and statistical analysis. The descriptive analysis presented tabular and graphical representations of some of the key variables from each construct. The statistical analysis includes the formation of a series of hypotheses with variables, and statistical tests to support each RQ. The statistical tests used include the t-tests, chi-square test, and correlation analysis. ANOVA was not used as it does not support statistical analysis between categorical variables. Figure 1.0 indicates the high level relationship between the six constructs and the RQ’s that is linked by different colored arrows. Further, Figure 1 expands into Table 1.0 by including the variables needed to support each RQ. Constructs Research Questions (B) Importance of SC (C) Current level of SCI,IS & SCV RQ1 (A) Organisation Dimensions Common to 3 RQs RQ2 (D) Understanding of SCI,IS, & SCV RQ3 (E) Development of SCI tool RQ1 RQ2 (F) Business Strategies RQ3 Figure 1.0: Hypothesis Model - linking constructs to research questions July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 16 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 The tests of means is conducted to examine if the categories of the variables used to support RQ 1,2 and 3, differ statistically or have a difference in their population means (Ho: µ yes= µ no and H1: µ yes≠µ no). In order to test these variables, four survey questions with “yes” and “no” categories were tested using with t-tests. These questions are located in Table 1.0 (shaded in yellow) as follows: Do you currently measure your SC performance?; Does your organization’s SC cross geographic boundaries?; Does your organization currently have a systematic approach for SC planning (such as a framework/platform) in place?; and Has your organisation clearly documented its business scenarios in terms of business model and SC partners. The t-tests indicated, whilst the results are not reported, that the categories of the dependant variables in column 1 to 6 of Table 1.0 had a difference in their population means and therefore further statistical analysis can now be applied. The hypotheses are formed with variables within column 1, and in between column 1 and column 2 to 6. The hypothesis are tested for strength of its relationship using correlation analysis and followed by further examination of its significance using chi-square tests. Variables Table 1.0: Link between constructs, research questions, and variables 1 2 3 4 5 6 Constructs A Constructs B Constructs C Constructs D Constructs E Constructs F RQ1,2,3 RQ 1 & 2 RQ 1,2 & 3 RQ 1 & 2 RQ 3 RQ 3 Level of management % of SC in country of operations Level of SCI – supply chain integration highly visible SC beneficial Factors for developing a integration tool No supply points % of SC in Australia Level of ISinformation sharing SCV will increase through reengineering of business processes Data an organization prepared to share No distribution Issues and Level of SCVsupply chain sharing info can Integrating July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK Business Strategy Manufacturing 17 Variabl es 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 1 2 3 4 5 6 Constructs A Constructs B Constructs C Constructs D Constructs E Constructs F RQ1,2,3 RQ 1 & 2 RQ 1,2 & 3 RQ 1 & 2 RQ 3 RQ 3 points concerns for SC visibility increase SCV strategies Strategy No of end to end SC partners Seamless SC Planning Type of information shared Ability to influence SC players Outcomes of integration Planning strategy Methodology in SC planning Key performance measures for SC ability to influence SC players Criteria for Sales Marketing Industry type sharing info Strategy Region of operations Impediments to SC planning level of understanding of other SC players info Inventory Management Strategy Business Activity Variables for t-tests Currently measure SC performance? Procurement Strategy Currently measure SC performance? Documentation of business scenarios? Systematic approach for SC planning? Does your organisation cross boundaries? Descriptive Analysis The breakdown of the survey responses by industry types indicated 22% and 14% of respondents belonged to FMCG and Pharmaceutical respectively. Moreover 52% of respondents are senior executives made up of 39% at General Manager level and 13% at CEO level and simultaneously 50% of the CEO’s lead transportation businesses. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 18 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 The variables included in the organisation dimensions such as sales volume, no of end-to-end SC partners and number of employees are summarized in Table 1.0, whilst the reported levels of SCI, IS and SCV are presented in Table 2.0. These variables form the basis of hypotheses formation across RQ1, 2 and 3. In defining the various levels of SCV and SCI (Table 2.0) the categories ‘High’, ‘Medium’, ‘Moderate’, ‘Limited’ and ‘No’, represented by an increasing scale 1 to 5 where 5 is the highest and 1 is the lowest. The level of SCV were categorised as “high visibility”, “medium visibility”, “moderate”, “limited visibility” and “no visibility”. Whilst the level of information sharing is categorised into “in depth”, “moderate”, “some extent”, “little” and “none”. These levels are based on the respondents perception of the current level of SCI, IS and SCV in their respective organisations. Further there is limited research supporting in ranking these levels, although some researchers have applied a scoring system. Concurrently, Barratt and Oke (2007) in their studies relating to SCV have also adopted high visibility, low visibility and medium visibility as categories describing the level of SCV. For the purpose of this research the categories applied the variables are based on what the responding organisation’s perceived level of SCI, IS and SCV as there is limited research studies in this area. It is observed that majority of responding organisations have a moderate level of SCI and level of SCV sharing only selected information amongst SC partners. Table 2.0: Key organisation dimensions Sales Volume Frequency No of end to end SC players Frequency No of employees Frequency < 50 mil 2 3% 3 and 5 13 20% < 500 16 25% 50 to 250 mil 15 23% 5 and 8 15 23% 500 to 2500 16 25% 250 mil to 1 bil 12 19% 8 to 12 5 8% 2500 to 10000 13 20% 1 bil to 5 bil 15 23% 12 and 15 16 25% >10000 19 30% > 5 bil 20 31% >15 15 23% Total 64 100 Total 64 100 Total 64 100 July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 19 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Table 3.0: Current Level of SCV, IS and SCI Current Level of SCI Frequency Current level of IS Frequency Current Level of SCV Frequency High Integration 6 9% All 8 13% High Visibility 13 20% Medium Integration 14 22% Moderate 15 23% Medium Visibility 13 20% Moderate Integration 25 39% Selected 16 25% Moderate Visibility 18 28% Limited Integration 16 25% Limited 15 23% Limited Visibility 12 19% No Integration 3 5% None 10 16% No Visibility 8 13% Total 64 100 Total 64 100 Total 64 100 Table 4.0 provides a summary (color coded) of the key variables used in the formation of hypothesis to support RQ2. It was observed that there is a strong support for IS, SCV and SCI in terms of redefining internal business processes to gain SCV and sharing of operating data in an integrated environment. Further the sharing of operating information can increase an organisation’s SCV, hence it can be argued that IS, SCI and SCV could be the key to minimising SC myopia. Table 4.0: Current level of understanding of SCI, IS and SCV in organisations Variable Strongly Disagree Moderately Disagree Slightly Disagree Neutral Slightly Agree Moderately Agree Strongly Sharing operating data in SCI environment 2% 2% 6% 15% 20% 20% 27% Benefit in having high SCV 0% 2% 2% 5% 20% 28% 44% SCV requires reengineering of business processes 0% 2% 5% 6% 17% 36% 34% Increase in SCV will increase SC costs 6% 31% 9% 19% 22% 9% 3% IS will increase SCV 0% 2% 2% 3% 28% 42% 23% Agree In examining the key variables that support RQ3 it was found there is an existing lack of trust between SC partners as there is a need for a formalised structure (Fig 3.0) with 72% of July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 20 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 respondents supporting the need of a mechanism to monitor information flow, 78% supporting information protection, whilst 63% highlighting the need for legal obligations and 56% valuing internet security. It may be argued that these findings indicate organisations are willing to share information under a governance process. Figure 2.0: Factors for developing a SCI tool Figure 3.0: Criteria for effective integration In developing such a framework (Fig 2.0), 88% of organisations placed importance in information security and 78% implied costs are important. Whilst there is empirical evidence indicating that organisations are concerned about SCV, SCI, SC flexibility and information security, in order to be conclusive it will be necessary to statistically test them with other variables such as the organisation dimensions. The possible outcomes of integration as a result of IS where 45% of organisations believe that there is a moderate case for organisational boundaries will be blurred through ongoing SCI whilst 19% indicated there will be a shift from monopoly to oligopoly and 23% of organisations indicated there will be a shift in power bases amongst SC partners. Statistical Analysis A series of hypothesis are formed to support each RQ. However, prior to conducting any statistical analysis, the t-tests are used to determine if there is a difference in population means between its categories and in addition normality tests are carried out to examine if the July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 21 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 data is distributed normally. Following the t-tests, 88, 108 and 54 possible hypotheses were identified to support RQ 1, 2 and 3 respectively based on combinations of variables indicated on Table 1.0. These hypotheses incorporated key variables such management level, size of an organisation, outcomes of integration, current level of SCV, SCI and IS between SC players. Each hypothesis consists of a null hypothesis (Ho) in which the variables (e.g. number of employees and the current level of SCI) had an independent relationship and alternative hypothesis (H1) that proposed dependency between the variables. It was found that 11 hypothesis were significant (at = <0.1) by applying Chi-square tests supporting RQ 1, 2 and 3 are reported. Further, some of the contingency tables were collapsed resulting in 3 by 4 tables due to insufficient expected number of observations in some cells. The research work of Pearcy and Giunipero (2008), Caglianao and Spina (2005), Wang and Wei (2007), Kwon and Suh (2004), Vereecke and Muylle (2006) and Johnson et al. (2007) in the area of SCM were reviewed, although it highlighted there is limited relevance to meet the needs RQ 1, 2 and 3, the approach taken is of importance, thus further strengthening the need for this research. The following observations were made:(1) the researchers used organisation dimensions such as size of firm, level of management and information visibility to form hypothesis (2) hypothesis formation between non organisational dimensions such as structural collaboration and performance improvement (3) the depth and the breadth of the research focused on technology related issues such SC collaboration, e-procurement instead of management issues dealing with SCV, IS and SCI incorporation in an organisation. The following hypothesis found to be statistically significant in support of research questions (RQs) 1, 2 and 3 are presented as follows: July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 22 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 RQ1: What is the current state of SCI, IS and SCV in organisations across a SC? 1. Ho: There is no relationship between the number of employees and current level of SCI, H1: There is a relationship between the number of employees and current level of SCI. 2. Ho: There is no relationship between the number of employees and the current level of SCV, H1: There is a relationship between the number of employees and the current level of SCV. 3. Ho: The current level of SC1 has no influence the current level of SCV in an organisation, H1: The current level of SC1 can influence the current level of SCV in an organisation. 4. Ho: There is no relationship between level of management and the benefit of having a highly visible SC, H1: There is a relationship between level of management and the benefit of having a highly visible SC. 5. Ho: There is no relationship between the type of business activity and the current level of SCV, H1: There is a relationship between the type of business activity and the current level of SCV. RQ2: What degree of SCV, IS and SCV are required by management in strategising and operationalising the desired aspects of SCV, SCI and IS in a collaborative SC? 6. Ho: There is no relationship between the number of end-to-end SC partners, and the current level of understanding of key operating data of SC players, H1: There is a relationship between the number of end-to-end SC partners, and the current level of understanding of key operating data of SC players. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 23 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 7. Ho: There is no relationship between redefining internal processes to gain SCV and the increase in SCV that will in turn increase SC costs, H1: There is a relationship between redefining internal processes to gain SCV and the increase in SCV that will in turn increase SC costs. 8. Ho: There is no relationship between the numbers of end-to-end SC partners, and increasing SCV can in turn increase SC costs, H1: There is a relationship between the numbers of end-to-end SC partners, and increasing SCV can in turn increase SC costs. 9. Ho: There is no relationship between the levels of management and increasing SCV can in turn increase SC costs, H1: There is a relationship between the levels of management and increasing SCV can in turn increase SC costs. RQ 3: What attributes (strategies, philosophies, processes, tools, systems) and frameworks are required by management in operationalising and strategising SCI, SCV and IS in a collaborative environment? 10. Ho: There is no relationship between the number of end-to-end SC partners, and the current level of understanding of key operating data of SC players, H1: There is a relationship between the number of end-to-end SC partners, and the current level of understanding of key operating data of SC players. 11. Ho: The current level of SCV has no relationship on the outcomes of integration in organisations, H1: The current level of SCV has a relationship on the outcomes of integration in organisations . Research findings and recommendations The statistical tests (Table 5.0) present the results for hypothesis supporting RQ 1, 2 and 3. In support of RQ1, the correlation analysis for hypothesis 1, indicated a significant correlation July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 24 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 between the size of an organisation (based on the number employees), and the level of SCI (p<0.05), therefore reject Ho. Hence, it can be argued that larger organisations dominate the level of SCI, which is supported in this paper by several researchers (Chapman et al., 2007 and Frohlich, 2002), furthermore significance testing found (p=0.054) supports the case. There is limited correlation between the size of an organisation, and its level of SCV, as indicated by hypothesis 2 although not significant at 5% but significant at 10% (p= 0.065, reject Ho at 10%). However, literature review indicates limited research has been carried out to support this hypothesis. Interestingly, there is a strong correlation between the level of SCI and SCV, corr coeff r = 0.361 and p<0.05, reject Ho, indicating that SCV increases with SCI. The literature review found the definition of SCV itself is unclear despite the advancement of SCI technology in organisations, hence there is a certain amount of ambiguity. Despite these ambiguities organisations can leverage of these findings to address issues relating to postponement and outsourcing from other countries minimise SC uncertainties in these areas. The level of management and the benefit of having a highly visible SC supported by (hypothesis 4) indicated a negative correlation (r = - 0.161, and not significant at 5% but is at 10%, p = 0.098), hence it appears that senior management see a lesser need for a highly visible SC than operational managers. Contrary to these findings, it is recommended to all levels of management in organisations that a highly visibly SC is beneficial in minimising SC myopia. There is limited correlation (r = 0.08) between (hypothesis 5) the business activity of an organisation and the level of its SCI (p < 0.10), however there is limited research available as other researchers have not fully explored these two components, the descriptive analysis of this research found 36% of respondents belonged to pharmaceutical and FMCG businesses hence the expectation of a significant correlation. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 25 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 There is significant correlation between redefining of internal processes to gain SCV and any increase in SCV that will in turn increase SC costs, (hypothesis 7), (p=0), giving an indication to management in organisations in relation to RQ2 that costs and benefits associated with SCI and SCV must be closely examined prior to its incorporation in organisations, hence management must weigh the benefits of minimising SC myopia against the incremental costs incurred. Although (hypothesis 8) and (hypothesis 9) indicated limited and weak correlation, there is some evidence that both the level of management and the end to end SC partners play a key role in the case where increasing SCV can in turn increase SC costs, supported sig (p<0.05). Hence CEOs need to justify any incremental costs in the minimisation of SC myopia. In support of RQ3, although a weak relationship was identified significant at 5% (p = 0.045, hence accept Ho) and whilst other researchers have examined areas such as the relationship of IS as a result of IT applications, (hypothesis 10) the greater the number of end to end SC players the higher level of understanding of SC partners key operating information has not been fully explored. However, the descriptive analysis found there is support for a mechanism to monitor information flow, a need for information protection and Internet security in sharing data among SC partners. Consequently with this view, it is recommended that management/ CEOs introduce frameworks/mechanisms for their global supply chains that will enable continuous information flow to minimise SC myopia, particularly in managing disasters such as a September 11. Table 5.0 Summary of test results Chi square analysis Correlation Analysis 2 values July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK p-value (p) Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) p –value 26 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Chi square analysis Correlation Analysis RQ1 RQ2 RQ3 H1 12.36 0.054 0.264 0.035 H2 13.994 0.065 0.120 0.344 H3 8.529 0.083 0.361 0.003 H4 7.840 0.098 -0.161 0.204 H5 12.435 0.053 0.08 0.485 H6 10.334 0.035 0.000 0.998 H7 114.129 0.000 0.605 0.000 H8 12.996 0.043 0.076 0.550 H9 12.453 0.014 0.074 0.559 H10 9.716 0.045 0.035 0.783 H11 11.705 0.069 0.099 0.435 It was observed (hypothesis 11) the higher the current level of SCV the more profound the outcomes are such as blurring of organisational boundaries or a shift in power bases along the SC supported by a weak relationship (r = 0.099) but significant at 10% (p = 0.069). However, descriptive analysis indicate organisations place importance on the outcomes of integration, such as a shift in power bases, a shift from monopoly to oligopoly and the blurring of organisational boundaries further supported by literature review that ongoing SCI leads to blurring of organisational boundaries. Based on this research findings senior managers in organisations can predetermine the degree of IS, SCI and SCV required in their supply chains. This is particularly important for organisations engaged in LSP activities where a substantial numbers of mergers and takeovers have materialised, evidenced by literature review to strategically position their businesses for each SC account or major customers. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 27 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Limitations The limitations of this research study included the use of categorical data as organisations are usually not willing to reveal the exact amount sales volume in dollar terms or number of employees resulting in the use of categorical data. Hence, limiting statistical analysis with only non parametric tests for this research. In addition the survey questionnaire should have included the academic qualifications of the respondent to gain further understanding of the respondents’ view of their interpretation of the different levels of SCV, IS and SCI. Furthermore additional samples are being collected with the aim getting improved statistical analysis. Conclusions and Further Research SC myopia is not a popular terminology in SC research publications. However, there is evidence that it can be reduced by increasing the level of SCI in overlapping supply chains, although similar effects are not observed with SCV and IS. The research study found senior or strategic managers envisages lesser need for a highly visible SC than managers at an operational level. Moreover, industry practitioners were found to have a clear understanding of SCI, IS, and SCV in the context of SCM although literature review found the opposite. Further, the level of SCI, IS and SCV is influenced by the size of an organisaton, industry type and the number of end to end SC partners. The findings of literature review, descriptive analysis and hypothesis testing were synthesised into a series of antidotes recommended to managers or practitioners aimed at minimising SC myopia and uncertainties. Future researchers could add value by investigating supply chain strategies to minimise uncertainties. REFERENCES July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 28 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 1. Akkermans, H., P. Bogerd, and Vos, B. (1999). Viturous and vicious cycles on the road towards international supply chain management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 19, no. 5/6, pp. 565-82. 2. Anonymous (2009). Visibility is the key supply chain challenge. Logistics Manager, vol. Apr, p. 7. 3. Atkinson, W. (2001). Gaining Supply Chain Visibility: The ability to see what is moving through your supply chain and when can give you an important competitive advantage. Supply Chain Management Review, vol (1), November 15. 4. Attaran, M. and Attaran, S. (2007). Collabrative supply Chain Management: The most promising practice for building efficicent and sustainable supply chains. Business Process Management Journal, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 390- 404. 5. Barratt, M. and Oke, A. (2007). Antecedents of supply chain visibility in retail supply chains: A resource based theory perspective. Journal of Operations Management, vol. 26, pp. 1217-33. 6. Bond, B., Genovese, Y.,Miklovic, D., Wood, N, Zrinsek, B. and Rayner, N. (2000). ERP is Dead- Long Live ERP 11, Gartner Group, New York, NY. 7. Bowman, C. and Ambrosini, V. (2000). Value creation versus value capture: towards a coherent definition of value in strategy. British Journal of Management, 11, pp. 1-15. 8. Bowersox, D.J., Closs, D.J. and Cooper, M.B. (2007). Supply Chain Logistics Management, McGraw-Hill, New York. 9. Cagliano, R., Caniato, F. and.Spina, G. (2005). How companies are shaping their supply chain through the internet, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 25 no. 12 p. 1309. 10. Clements, M. D. and O'Loughlin, A. (2007). Supply chain myopia: a conceptual framework. International Research Conference on Quality, Innovation and Knowledge Management, (pp. 610-620). India: Monash University. 11. Chapman, R. L., Chapman, G. and Sloan, T. (2007). Up and Down the supply chain- How company size and strategy relate to the the level of integration and its benefits', paper presented to QIK Quality Innovation and Knowledge New Delhi. 12. Davenport, H. T. and Brooks, J. D. (2004).Enterprise systems and the supply chain', Journal of Enterprise Information Management,. vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 8-19. 13. Dwyer, K. (2006). Seeing Straight, Canadian Transportation Logistic., vol (109), Sep , no. 9, p. 11. 14. Fabbe-Costes, N., Jahre, M. and Roussat, C. (2009).Supply Chain Integration:the role of service providers, International Journal of Productivity & Performance Management, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 71-91. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 29 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 15. Fawcett, S. E. and Magnan, G. M. (2002).The rhetoric and reality of supply chain integration, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 339-61. 16. Fliedner, G. (2003). CPFR: an emerging supply chain tool. Industrial Management & Data Systems, vol. 103, no. 1 pp. 14-21. 17. Francis, V. (2008). Supply Chain visibility : Lost in translation?. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 180 - 4. 18. Gundlach, G. T., Bolumole, Y. A., Eltantawy, R. A. & Frankel, R. (2006).The changing landscapeof supply chainmanagement, marketing channels of distribution, logistics and purchasing. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 428-38. 19. Hamilton, P. W. (1994).Getting a grip on inventory', Dun and Bradstreet Reports, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 30-32. 20. Harps, L. & Hansen, L. (2000).The haves and have nots:supply chain practicesfor the new millennium, Inbound Logistics, vol. 3 January, pp. 75-111. 21. Haydock, M. P. (2003). Supply Chain Intelligence, Ascet Volume 6:Achieving Supply Chain Excellence through Technology, vol. 5, pp. 15-21. 22. Hertz, S. (2006). Supply chain myopia and overlapping supply chains, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 208- 17. 23. Hugos, M. (2006). Essentials of Supply Chain Management, Second Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New Jersey. 24. Johnson, P. F., Klassen, R. D., Leenders, M. R. and Awaysheh, A. (2007). Selection of planned supply initiatives: the role of senior management expertise chain, International Journal of Operations Management, vol. 27, no. 12, pp. 1280-302. 25. Katunzi, T. (2011). Obstacles to Process Integration along the Supply Chain: Manufacturing Firms Perspective, International Journal of Business and Management, vol. 6, no. 5 May, pp. 105-13. 26. Kilpatrick, J. and Factor, R. (2000). Logistics in Canada survey : tracking year 2000 supply chain issues and trends, Materials Management and Distribution, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 16-20. 27. Koh, L. S. C., Saad, S. and Arunachalam, S. (2006). Competing in the 21st century supply chain through supply chain management and enterprise resource planning integration, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. Bradford, vol. 36 no. 6 pp. 455-65. 28. Krishnamurthy, S. (2002), Supply Chain Intelligence, WIPRO Technologies. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 30 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 29. Kwon, I. W. G. & Suh, T. (2004 ). A global Review of Purchasing and Supply, The Journal of Supply Chain Management, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 31-46. 30. Langley, J. (2002). Supply Chain Visibility, Georgia Institute of Technology. 31. Lee, H. G., Clark, T. and Tan, K. Y. (1999). Can EDI benefit Adopters?, Information Systems Reseach, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 141-57. 32. Lewis, I. and Talalayevsky, A. (2004).Improving the interorganisational supply chain through optimisation of information flows, Journal of Enterprise Information Management, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 299-37. 33. Lieb, R. C. (2005). The 3PL industry: Where it's been, where it's going, Supply Chain Management Review, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 6-8. 34. Lieb, R. C. and Bentz, B. A. (2005). The use of third party logistics services by large American manufacturers: The 2003 survey, Transpiration Journal, vol. Summer 43, no. 3, pp. 24-33. 35. Ludvigsen, J. (2000). The international networking between logistical operators', Stockholm School of Economics 36. Mahadevan, K. and Samaranayake, P. (2006). A Conceptual Framework for Reverse Logistics in the Consumer Electronics Industry, 4th ANZAM Operations Management Conference, University of Wellington, N.Z. . 37. Mentzer, J. T., Min, S. and Bobbitt, L. M. (2004).Toward a unified theory of logistics , International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 608-27. 38. McLaren, T., Head, M. and Yuan, Y. (2002). Supply Chain Collabration alternatives:understanding the expected costs and benefits, Internet Research:Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 348-64. 39. Moller, C. (2005). ERP 11: a conceptual framework for next-generation enterprise systems?, Journal of Enterprise Information Management, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 483-497. 40. Mortensen, O. and Lemoine, O. W. (2008). Integration between manufacturers and third party logistics providers?, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 331-359. 41. O'Toole, K. and Robinson, J. (1999). Internet trade puts pressure on businesses http://news-service.standford.edu/,<http://newsservice.Standford.edu/news/1999/May12/e-ecommerce-512.html>. 42. Pearcy, D. H. and Giunipero, L. C. (2008).Using e-procurement applications to achieve integration: what role does firm size play?, Supply Chain Management Journal, vol. 13, no. 1. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 31 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 43. Power, D. J. (2005). Supply Chain Management integration and implementation : a literature review, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 252- 265. 44. Prabhaker, P. (2001). Integrated marketing-manufacturing strategies, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 113-128. 45. Priesmeyer, R.H, Seigfried R.J. and Murray M.A. (2012).The whole supply chain as a wholistic system: a case study, Marketing & Management Challenges for the Knowledge Society vol 7, no 4, pp 554-564. 46. Rai, A. and Bush, A. A. (2007). Recalibrating Demand- Supply Chains for the Digital Economy, Systems d’Information et Management:, vol. Jun 12, no. 2, pp. 21-52. 47. Rajib, P., Tiwari.D. and Srivastava, G. (2002). Design and Development of amn integrated supply chain management system in an internet enviroment , Journal of services Research, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 21-52. 48. Rogers, D. S. and Tibben-Lembke, R. S. (1998). Going Backwards: Reverse Logistics Trends and Practices, The University of Nevada,, Center for Logistics Management, Reverse Logistics Council., Reno. 49. Samaranayake, P. (2005). A conceptual framework for supply chain management: a structural integration, Supply Chain Management Review, vol. 10 no. 1, pp. 47-59. 50. Sandoe, K., Corbitt, G. and Boykin, R. (2001), Enterprise Integration John Wiley and Sons Inc, New York. 51. Scalet, S. D. (2001).The cost of secrecy, CIO Magazine, vol. July 15, no. 1, p. 54. 52. Shehab, E. M., Sharp, M. W., Supramanian, L. and Spedding, T. A. (2004).Enterprise Resrources Planning: An Integrative view, Business Processes Management Journal, vol. 10, no. 4 pp. 359 -86. 53. Simchi-Levi, D., Kaminsky, P. and Simchi-Levi, E. (eds) 2000. Designing and Managing the Supply Chain: Concepts, Strategies and Case Studies, McGraw-Hill., NY.USA: . 54. Skjoett-Larsen, T., Ternoe, C. and Andersen, C. (2003). Supply Chain Collaboration: Theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, vol. 33, no. 6, p. 531. 55. Speier, C., Mollenkopf, D. and Stank, T. P. (2008). The Role of Information Integration in Facilitating 21st Century Supply Chains: A Theory Based Perspective, Transportation Journal, vol. Spring 47, no. 2, p. 21. 56. Stank, T. P., Keller, S. B. and Closs, D. J. (2001). Performance Benefits of Supply Chain Logistical Integration, Transportation Journal, vol. Winter; 41, no. 2/3, pp. 32-46. 57. Stedman, C. (1998). Retailers face team-planning hurdles, Computerworld, vol. 32, no. .42, pp. 6-9. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 32 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 58. Stein, T. (1998).Extending ERP', Information Week, vol. No. 686, no. 15 June, pp. 75-82. 59. Storey, J., Emberson, C., Godsell, J. and Harrison.A. (2006). Supply chain management: theory and practice –theory, practice and future challenges, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 754-74. 60. Swaminathan, J. M. and Tayur, S. R. (2003). Models for Supply Chains in E-Business, Management Science, vol. 49 October, no. 10, pp. 1387- 406. 61. Tan, K. C., Lyman, S. B. and Wisner, J. D. (2002).Supply Chain management: a strategic perspective, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 614-631. 62. Tarn, J. M., Yen, D. Y. and Beaumont, M. (2002).Exploring the rationales for ERP and SCM integration, Industrial Management & Data Systems, vol. 102, no.1, pp. 26-34. 63. Thomas., J. (1999).Why your Supply Chain does not work?, Logistics and Management Report, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 42-44. 64. Thompson, A. A. and Strickland, A. J. (1998), Strategic Management- Concepts and Cases, Tenth Edition edn, Irwin McGraw- Hill 65. Van Laneghem, H. and Vanmaele, H. (2002).Robust planning: a new paradigm for demand chain planning, Journal of Operations Management, vol. 20, pp. 763-83. 66. Vereecke, A. and Muylee, S. (2006).Performance improvement through supply chain collaboration in Europe, International Journal of Operations Production Management, vol. 26, no. 11, pp. 1176-98. 67. Wang, E. T. G. and Wei, H.L. (2007). Inter-organizational Governance Value Creation: Coordinating for Information Visibility and Flexibility in Supply Chains, Decision Sciences, vol. 38, no. Atlanta 38 pp. 647 - 74. 68. Whipple, J. S., Frankel, R. and Anselmi, D. (1999).The effect of goverenance structiure on performance: a case study of efficicent consumer response, Journal of Business Logistics, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 43-62. 69. Wisner, J. D., Leong, G. K. and Tan, K. C. (2005). Principles of Supply Chain Management: A Balanced Approach Thomson South Western, Ohio. 70. Wollman, T. E., Berry, L. B. and Whybark, D. C. (1997). Manufacturing Planning and Control Systems, Irwin/McGraw - Hill July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 33