Poland, The European Union, And The Euro: Poland’s Long Journey To Full European Integration

advertisement

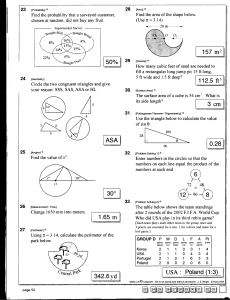

2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 POLAND, THE EUROPEAN UNION, AND THE EURO: Poland’s Long Journey to Full European Integration By Richard J. Hunter, Jr. * And Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V.** “I am convinced that Poland is ready for a civilisational acceleration, although the world is being shaken by the economic crisis.” Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk ABSTRACT This article will discuss the political and economic background behind Poland’s decision to join the Euro-Zone, perhaps as early as 2012. The article describes important political events and summarizes key economic data presented at the end of 2008, as well as providing important “pro and con” arguments surrounding this controversial move. In addition, the article provides a context to Poland’s “march to Europe,” as it has moved to full membership in the European Union, including its single currency. 1. Introduction On January 1, 1999, Europe launched its “grand experiment with a shared currency” with four purposes in mind: to lower borrowing costs; ease restrictions on trade and tourism; boost economic growth, development, and foreign direct investment and; and strengthen the European community. In fact, in the last six years alone, 15 million new jobs have been created by “making trade and travel easier through a single currency.”1 With the inclusion of Slovakia in the single currency on January 1, 2009,2 328 million of the 500 million people in the European Union will share the single See Matt Moore & George Frey, “Euro Currency turns 10; seen fulfilling promise,” Aruba News, citing the Associated Press, December 29, 2008, p. B8. Not all of the news has been positive, however. In January of 2009, the International Herald Tribune reported that economic sentiment had “plunged to an all-time low in December.” The European Commission’s business climate index tumbled by -3.17 points—the lowest level reached since records started in 1985. “Economic sentiment plunges in euro zone,” International Herald Tribune, citing Reuters, at http://www.iht.com/articles/2009/01/08/business/euecon.php (January 8, 2009). 1 For a discussion of the Slovak decision, see “Slovakia hopes euro move brings stability,” at http://edition.cnn.com/2008/BUSINESS/12/31/euro.slovakia/index.html, December 31, 2008. 2 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 1 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 currency. When Poland joined the European Union in 2004, it committed itself to adopt the euro, the currency of the European Union (EU),3 as its national currency at some “appropriate time” in the future. With the fear that a continued depreciation of the Polish zloty against the euro might result in “higher loan repayments” than investors had foreseen, many Poles have found it increasingly difficult to repay euro-denominated loans with rapidly depreciating Polish currency. A move to adopt the euro was seen as a remedy for this potential difficulty. Nevertheless, a debate has emerged concerning the implementation of this strategy.4 In November of 2008, Poland’s government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Donald Tusk, announced a plan, or what it described as a “roadmap,”5 to adopt the euro by 2012, although the Prime Minister stated that should adverse circumstances arise, the plan was open to “discussion.”6 This move, although not altogether unanticipated, was nonetheless controversial since it would require an amendment to Poland’s Constitution and would also require the unusual cooperation of Poland’s two major political parties—now bitter rivals on the Polish political scene. The current version of Poland’s Constitution7 allows only Poland’s Central Bank For a general discussion of the euro at its 10th “birthday,” see Joanna Slater & Joellen Perry, “On Euro’s 10th Birthday, No Music,” Wall Street Journal, December 16, 2008, p. C1. The authors note: “Even as some countries are eager to crowd under the euro’s umbrella, the financial crisis and deepening recession have unleashed the biggest challenge of European currency’s lifetime.” 3 See, e.g., John Czop, “The Euro and Poland’s Security,” The Post Eagle (Clifton, N.J.), December 10, 2008, p. 2. The author notes that this negative may impact adversely on Poland’s ability to guaranty its national defense in a time of increasing tension with the “former” Soviet Union over United States’ plans to include Poland in a Western European “nuclear shield.” 4 See “Poland may get referendum on euro,” BBC News, at http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk, October 28, 2008. For an outline of Poland’s probable steps towards adoption of the euro, see the Appendix, “The Path to the Euro.” 5 6 Polish News Bulletin, December 10, 2008, quoting Gazeta, December 9, 2008. 7 Adopted by National Assembly on April 2, 1997; Confirmed by Referendum in October 1997. Dziennik Ustaw, No. 78, item 483 (1997). According to Section 2 of Article 227, “the organs of the National Bank of Poland shall be: the President of the National Bank of Poland, the Council for Monetary Policy as well as the Board of the National Bank of Poland.” The Polish Constitution of 1997 is organized as follows: Chapter I - The Republic Chapter II - The Freedoms, Rights and Obligations of Persons and Citizens Chapter III - Sources of Law Chapter IV - The Sejm and the Senate Chapter V - The President of the Republic of Poland Chapter VI - The Council of Ministers and Government Administration Chapter VII - Local Self- Government Chapter VIII - Courts and Tribunals June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 2 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 (Narodowy Bank Polski–NBP) to set monetary policy.8 So, any plan to adopt the euro and scrap the Polish zloty and swap it for the euro9 would require a change in Poland’s constitution as well as possibly necessitating holding a national referendum on the issue, although a national referendum is not strictly required to amend the Polish Constitution. The mechanism of adopting the euro will be fully discussed in Part 4 of this paper. How did Poland travel down this path towards full participation, not only in Europe’s political and economic integration, but also in the full integration of Poland’s monetary system with sixteen nations which have adopted the euro as their medium of exchange?10 2. Poland’s Accession to the European Union in 2004─A Brief Look Back11 Chapter IX - Organs of State Control and for Defense Of Rights Chapter X -Public Finances Chapter XI - Extraordinary Measures Chapter XII - Amending the Constitution Chapter XIII - Final and Transitional Provisions 8 For a detailed discussion of the NBP and the role of its former President, Leszek Balcerowicz, see Richard J. Hunter, Jr. & Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V., “A Primer on the National Bank of Poland: A Central Institution in the Transformation Process,” European Journal of Economics, Finance, and Administrative Sciences (on line), Vol. 1, No. 1 (2005). 9 Analysts from JP Morgan stated that it expected that the zloty would strengthen against the euro to 2.81 at the end of 2009. The U.S. dollar was expected to weaken to 2.25 zlotys at the end of 2009. Reported in PAP News Wire, December 11, 2008. 10 It appears that Iceland and Denmark may likewise be reconsidering earlier decisions taken not to join the euro-zone, which currently consists of sixteen nations. When the euro was initially launched for “non-cash,” financial transactional purposes in 1999, 11 countries were part of the arrangement: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, and Spain. Bank notes and coins were added on January 1, 2002. The original group has been joined by Cyprus, Greece, Malta, and Slovenia. With the inclusion of Slovakia on January 1, 2009, the total is now 16. Iceland had rejected calls to join the European Union itself, on grounds of protecting its “national sovereignty,” fearing that “the bloc’s common fisheries policy would strip it of control over a vital natural resource. However, in the fall of 2008, Iceland was forced to seek a loan from the International Monetary Fund, as its currency fell by 80 percent against the euro. As of December 2008, 60 to 70 percent of Icelanders now favored joining the EU. See Carter Dougherty, “Some Nations That Spurned the Euro Reconsider,” New York Times (on line), at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/02/business/worldbusiness/o2euro.html, December 2, 2008. Denmark had rejected the common currency in two national referenda—the most recent of which occurred in 2000, spurred by opposition from the Socialist People’s Party which was concerned about currency speculation and making the EU’s agricultural policies more environmentally friendly. Id. Current poling data in Poland indicates a similar 60 to 70% of Poles favoring the adoption of the euro. For a contextual discussion of the issue of Poland’s accession to the European Union within the broader range of issues concerning Poland’s economic and political transformation, see Richard J. Hunter, Jr., Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V. & Robert E. Shapiro, Poland: A Transitional Analysis, pp. 125-145 (2003). This section of the paper has been adapted from Richard J. Hunter, Jr. & Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V., “The Ten Most Important Economic and Political Events Since the Onset of the Transition in Post-Communist Poland,” The Polish Review, Vol. LIII(2), pp. 183-216, 203-209 (2008). 11 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 3 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 It may seem quite ironic now, but Poland’s “march to Europe” began even before the process of fundamental political and economic transformation had begun in 1989, when diplomatic relations were established between Poland and the European Economic Community in September 1988. In July 1989, the Polish Mission at the European Community was established in Brussels. In early 1990, Jan Kułakowski was appointed as Poland’s first ambassador to the European Union, a position he held until June 1996. The formal process of Poland’s reintegration into Europe began in May 1990, when the government of Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki submitted its official application for the opening of accession negotiations in Brussels. On 16 December 1991, Poland and the European Economic Community signed the European Treaty, assuring Poland’s associated country status.12 Poland’s eventual participation in the single currency would be contingent upon meeting the criteria established in the Maastricht Treaty. These criteria included targets for inflation, interest rates, government borrowing, and the size of government debt. Another important event occurred on 13 December 1993 when the EU summit in Copenhagen officially agreed to enlarge the membership of the organization and set a target date of May 2004 for the admission of new member states. The Copenhagen Summit approved ten new members—the majority of which had been members of the former Soviet Bloc and the Warsaw Pact. Poland would be the largest and most populous of the new EU member states—its population nearly one-half of all candidate EU members. The Minister of Foreign Affairs formally submitted Poland’s application in April of 1994. Poland’s accession would be assured by the satisfactory achievement of three requirements: Sustaining a functioning market economy with the capacity to meet competitive standards and market forces within the EU community; Stabilizing foundational political institutions, essentially providing evidence of a functioning “civil society,” including creating political and social institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, and respect for minority and human rights; and Demonstrating an ability to assume the obligations of full EU membership, including those delineated in the acquis communitaire, the body of the EU’s legislative requirements.13 In August 1996, the Committee for European Integration was established in Poland. The Committee consisted of a group of Cabinet Ministers who would bear direct 12 The European Treaty took effect on 1 February 1994. It provided for the gradual reduction of restrictions on trade in industrial goods between Poland and the European Economic Community (later, the European Union or EU) and for limited liberalization of trade in agriculture — the single issue that would continue to be the most vexing one in future negotiations between Poland and the EU. See European Council, “Conclusions of the Presidency,” Copenhagen, June 21-23, 1993, SN/180/93, p. 13, adapted from “Enlargement,” at http://europa.eu.int/comm/ enlargement/enlargement.htm. 13 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 4 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 responsibility for the integration process, with Professor Danuta Hubner of the Warsaw School of Economics serving as its first chair. In January 1997, the Polish Council of Ministers adopted the National Integration Strategy, a document that systematized integration responsibilities and tasks to be completed in the period preceding EU membership. Later, on 13 December 1997, the EU Summit in Luxembourg officially invited Poland and several Central European nations—the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Slovenia, as well as Cyprus—to initiate formal membership negotiations. The road for Poland, however, was not always a smooth one. In fact, negotiations would be long and difficult. Starting in 1997, the EU Commission began to issue regular progress reports on candidate nations. The Commission made it clear that progress would be judged not on the basis of uncertain promises or vague generalizations, but rather on the basis of “actual decisions taken, legislation actually adopted, international conventions actually ratified (with due attention being given to implementation), and measures actually implemented.” In its 1997 Opinion on Poland’s application for membership, the Commission concluded: “Poland’s political institutions function properly and are in a condition of stability…. There are no major problems over respect for fundamental rights. Poland presents the characteristics of a democracy, with stable institutions guaranteeing the rule of law, human rights and respect for protection of minorities.”14 The Report, however, noted that there were “certain limitations” on the freedom of the press (mainly, relating to media ownership questions) and that Poland had to “complete procedures for compensating those whose property was seized by the Nazis or Communists”—raising the delicate and difficult issue of reprivatization.15 The Commission’s conclusions regarding Poland may be found in “Agenda 2000, Commission Opinion on Poland’s Application for Membership in the European Union,” Brussels, July 15, 1997. See also Stefan Wagstyl, John Reed & Christopher Bobinski, “The Long March Towards Union with Europe,” Financial Times, April 17, 2000, p. I; “Milestones of Transition,” Transition, Vol. 11, No. 1, February 2000, pp. 16, 31, noting “Poland is urged to speed up EU entry process.” The web site for this World Bank publication is www.worldbank.org/html/prddr/trans/WEB/trans.htm. 14 15 Reprivatization is the process of identifying government-confiscated or nationalized property and attempting to return it to its rightful owners or to their heirs. Restitution means returning property to former owners; reprivatization signifies putting state property that had been confiscated from private owners back into private hands. “Reprivatization can refer to the restoration of property to the original proprietor; but it also describes transfer of state property (that once was private) to any private party. Finally, privatization (prywatyzacja) means making state property private.” See Marek Jan Chodakiewicz & Dan Currell, “Restyytucja: The Problems of Property Restitution in Poland (1939-2001),” in Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, John Radzilowski & Dariusz Tolczyk, eds., Poland's Transformation: A Work in Progress, pp.157-193 (2003). Because of the unique history of settlement of Jews in Poland prior to World War II, at issue may be more than 180,000 properties (among them claims by as many as 35,000 to 40,000 Jews) confiscated from private owners by the Nazis in occupied Poland (1939-1945) or by the Communist government (1945-1989). Many of these properties were sold or transferred to private individuals by the Polish government after the fall of Communism in 1989. Reprivatization is still quite controversial and remains politically unpopular in Poland. As noted by Joan Griffith, “ After avoiding the issue for more than 50 years, Poland is now considering claims of people of Polish descent who owned property before 1939.” See Joan Griffith, “Reprivatization: Claiming Family Property in Poland,” at http://www.polishclaims.com.html, cited in Richard J. Hunter & Leo V. Ryan, "A Field Report on the June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 5 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 The October 1999 Report of Commission President Romano Prodi, however, was less than positive for Poland and other Central European applicants. Prodi concluded that candidates had not “progressed significantly” in adapting legislation, institutions, and governmental structures to EU criteria. Specifically, the Prodi Report concluded that while Poland had made significant progress in establishing a market economy and in attaining institutional political stability, it had not achieved satisfactory progress in implementing reforms in such areas as curtailing government aid for ailing Polish industries (especially its dinosaurs or WOGs—the Polish acronym for “Great Economic Organizations”16), modernizing Poland’s agricultural sector, harmonizing its statutory framework to the acquis, and expanding its inadequate infrastructure, especially its backward network of roadways and highways. As 2001 arrived, Minister Kułakowski, still Poland’s chief negotiator in the Background and Processes of Privatization in Poland," Global Economy Journal, Vol. 8, Iss. 1, Article 5, at: http://www.bepress.com/gej/vol8/iss1/5 (2008). However, there are groups who are opposed to reprivatization, including those who may have acquired properties from the Polish government “in good faith,” as a part of a normal business operation, or through a sale or lease, and more problematically, those who own buildings on land with “questionable titles,” and whose property might have been acquired illegally and from whom they can trace their own now questionable or defective titles. Compensation has been the subject of heated, sometime tragically demagogic, debates in the Sejm, in the Polish mass media, in certain religious circles, and in the Polish legal system. Although numerous legislative proposals had been introduced in the parliament, none obtained the required majority for passage. In March 2001, the Parliament finally voted to enact a restitution law, but the law was vetoed by the former President, Aleksander Kwaśniewski on budgetary grounds. Despite the uncertainty and lack of legislative progress, the Ministry of the Treasury had assigned nearly $3 billion in funding for reprivatization efforts should a law eventually pass the Parliament. See also Toby Axelrod, “Polish Holocaust survivors press on with restitution claims,” at http://www.jta.org.html, April 7, 2004. It is also interesting to note that in October of 2008, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Poland owed no compensation to ethnic Germans expelled from its territory in 1945. In rejecting the claims of the group called “The Prussian Trust” (Preussische Truehand), the Court concluded that claims of inhumane treatment were inadmissible, as Poland did not have actual and de jure control of its German territory between January and April 1945, when the forced expulsions took place. The Court also concluded that the Polish Government could not have breached the European Convention of Human Rights and its core guarantees concerning property rights as Poland only ratified the treaty in 1994. See “Court Rejects German Compensation Claims Against Poland,” at www.djnews.plus.com, October 10, 2008. As an update, in late 2008, Marcin Zamojski reported that the Minister of the Treasury, Aleksander Grad, declared that a new reprivatization act would be circulated sent in November for an interdepartmental review and agreement. The Tusk government indicated that it would allocate 6 billion euro for this target. The act will specify the minimal sum of money that the government will spend for planned compensations. The Minister underlined that the budget could not afford to spend more for compensation. Minister Grad explained that the Polish inheritance law will be applied to the planned reprivatization. A right to make use of this compensation will apply to those who were citizens of Poland when their properties were nationalized. Such persons must also present suitable applications and provide evidence that they were the owners of the estates. Applications will be considered first in an administrative procedure. Then, a list of “proposed compensations” will be prepared. See Marcin Zamojski, “Six billion euro for reprivatization,” at www.news.Poland.com, September 22, 2008. See Ramnath Narayaswamy, “Poland: The Reform That Never Was,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 23, No. 16, pp. 778-779 (April 16, 1988), commenting on the relationship of the politicallyconnected WOGS to transformation of the Polish economy. 16 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 6 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 government of Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek, succinctly reiterated Poland’s objectives in joining the EU: Poland aims at a full-fledged membership in the EU, without any kind of secondclass membership; Poland wants to possess a “healthy economy” within the single European market and desires to be a “strong state” within the EU; Poland desires to be an active EU member, contributing to the stability and development of the region; and Poland is committed to the “idea of European integration” and to the full development of the European Union.17 By the time of its 2001 Regular Report, however, the Committee found that Poland had in fact “fulfilled the political criteria.” The Report continued: “Since that time [1999], the country has made considerable progress in further consolidating and deepening the stability of its institutions guaranteeing democracy.” A further Report, again more favorable to Polish interests, was issued in 2002.18 By the time the 2002 Report was issued, Poland had closed 27 of the negotiation “chapters” or outstanding issues. Again, while the Report was largely positive, there were still several negatives. On the negative side, the Report noted, “Corruption remains a cause for serious concern.” The Report suggested that the focus for the future must remain on ensuring “a coherent approach to corruption, implementing the legislation and above all on developing an administrative19 and business culture, which can resist corruption.”20 However, “Overall, Poland has achieved a high degree of alignment with the acquis in many areas.” In short, the Report concluded that Poland would be ready for Remarks of Minister Jan Kułakowski, Brussels, Center for European Policy Studies (CEPS), February 8, 2001, at http://ceps.be/Events/Webnotes/020801.php. 17 Commission on the European Communities, “2002 Regular Report on Poland’s Progress Toward Accession,” Brussels, October 9, 2002. Poland’s status on the various Chapters was evaluated in three sections — Progress, Assessment, and Conclusions, pp. 48-134. 18 Part of the reform of the administrative culture involves establishing what are termed “commonly accepted norms of civil service functioning,” including separation of the public and private sectors; separation of the political sphere from the bureaucratic one in decision making; assuring individual responsibility for decision-making; establishing clearly specified rights and duties, job protections, employment stability, and a pre-determined and specified level of state officials’ salaries; assuring open and competitive selection of employees; and assuring organizational promotion based on achievement at work and not on political connections. In short, administrative reforms were designed to assure the functioning of a civil society in Poland, as opposed to the continuance of the discredited nomenklatura system. See European Commission, “Report on the European Commission’s Reform,” March 2000, referenced in “Serving a More Perfect Union,” Polish Voice, No. 34, pp. 15, 17, July 31, 2003. Contrast this standard to an evaluation of the role of the nomenklatura in pre-transition Poland, a system which had become a “lunatic collage of incompetence, privilege, pandering and outright corruption.” See Lawrence Weschler, Solidarity: Poland in the Season of Its Passion, p. 46 (1982). 19 20 “2002 Regular Report on Poland’s Progress Toward Accession,” p. 20. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 7 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 entry into the EU in May 2004—but only if Polish voters concurred. referendum was scheduled for June 2003. A national The Agreement After a final round of intense diplomatic and political summitry, accession negotiations were completed on 13 December 2002 in Copenhagen when an agreement was reached on chapters involving Competition Policy, Agriculture, and Finance and Budget. Contrary to many negative expectations, Poland was able to negotiate final terms that were favorable both to Poland’s domestic and international positions.21 The negotiating team that Prime Minister Leszek Miller22 had assembled included “veteran” SLD members, Agriculture Minister Jarosław Kalinowski, Finance Minister Grzegorz Kołodko, Foreign Minister Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, and primary negotiators, Jan Truszyński and Minister for European Affairs, Professor Danuta Hubner. Building on nearly fifteen years of history, the group established a three-pronged strategy: negotiate additional budgetary concessions for Poland in order to meet anticipated accession costs and to reduce the potential negative effects of accession on the Polish budget; negotiate a more favorable scheme for Poland’s agricultural sector, especially in the first years of EU membership; and, on a more practical level, secure higher milk production quotas and agricultural parity payments.23 Success would be seen in all three major areas, as well as several others. Despite spirited opposition from many segments of Polish society—especially those on the “Polish right—throughout the period of negotiations concerning Polish accession to the EU, support for Poland’s entry into the EU remained relatively steady, in the range of 55 percent to 65 percent. At one point, in May 1996, support for the EU reached an incredible 80 percent. Considering the importance that all post-transition governments have placed on Polish accession to the EU, one can heartily agree with the sentiments expressed by European Commission President Romano Prodi, who had apparently experienced an epiphany concerning Poland’s accession to the EU: “A great, proud nation is turning the page of a tragic century and freely takes the seat that should have belonged to it right from the start of the process of European integration.”24 The “final” Polish position is outlined in Malgorzata Kaczorowska, “EU Negotiations: Milking an Issue,” Warsaw Voice, December 15, 2002, p. 5. 21 22 During the period immediately preceding the Denmark meeting, Prime Minister Miller met with the Prime Minister of Great Britain, the Prime Minister of Denmark, the Chancellor of Germany, the Prime Ministers of the Visegrad Group (the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia), the Prime Minister of Spain, the Prime Minister of Italy, Pope John Paul II, and the Prime Minister of Sweden in an unprecedented diplomatic effort to secure support for Poland’s EU membership application. These efforts resulted in significant support for Poland’s efforts to join the EU. See generally Malgorzata Kaczorowska, “Triumph of the Will,” Polish Voice, December 22-29, 2002, pp. 7-8; Post Eagle (Clifton, N.J.), January 22, 2003, pp. 1, 16. 23 Reported in Breffni O’Rourke, “Poland After EU Vote, Poles Wonder Where They Go From Here,” at http://www.cer.org.uk/articles/cer_inthepress_2003.html, June 9, 2003. This article also appeared 24 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 8 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Official results from the 7-8 June 2003 national referendum indicated that 77.45 percent of Polish voters approved Poland’s membership in the EU. The turnout was a surprising 58.85 percent, which was well over the required “50 percent plus 1” threshold required to make the result legally binding. At the signing of Poland’s accession treaty to the European Union on 23 July 2003, President Kwaśniewski added: “Who would imagine that one day, in this room, this same room in which on May 14, 1955, the Warsaw Pact was created, nearly 50 years later, we would witness Poland’s return to an undivided Europe.” It may be ironic in a historical sense that Germany’s Foreign Minister, Joschka Fischer, had become the most forceful advocate for EU enlargement, noting: “We must allow Poland in the heart of Europe, lest we accept the legacy of Hitler and Stalin.”25 The government of Prime Minister Leszek Miller formally brought Poland into the European Union on 1 May 2004—the day before Miller was forced to resign his position as Prime Minister amidst allegations of scandal and official corruption. The first Polish elections to the European Parliament were held on 13 June 2004. After more than four decades of isolation from its Western European roots, Polish membership in both NATO and the EU had finally begun to erase the tragedy and betrayal of Yalta and Potsdam and the legacy of a system that Stalin himself had reportedly once remarked “fits Poland like a saddle fits a cow.”26 3. The Political Context Despite a general consensus about Poland’s membership in the EU, there is a major split today in Poland over the adoption of the euro that cuts across deep partisan lines. Fundamental differences exist as a result of the parliamentary elections which took place in 2005, and those that occurred two years later, on 21 October 2007. A brief overview is in order to provide the proper political context. Polish Electoral Politics27 The parliamentary elections of 2005 had resulted in an overwhelming victory for two parties of the centre-right, the conservative Law and Justice (PiS) and the liberalconservative Citizens Platform (PO), and an overwhelming defeat for Poland’s poston the website of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 25 See “Kwaśniewski Ratifies Poland’s EU Vote,” Polonia Today, August 2003, p. 12. 26 Quoted in D.S. Mason, Revolution in East Central Europe, p. 40 (1992). For an interesting contemporary discussion of the decisions taken at Yalta, see H. W. Brands, Traitor to His Class, pp. 800803 (2008). Adapted from Richard J. Hunter, Jr. & Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V., “An Update on the Polish Economy: Meeting the Criteria for a ‘Normal Country,’” European Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 375381 (2008). 27 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 9 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 communist left. The center-left government of the Alliance of the Democratic Left (SLD) was soundly defeated. PiS and PO combined won 288 out of the 460 seats, while the SLD retained only 55 seats of the 216 seats they had won in the 2001 parliamentary elections. In the 2005 elections, PiS won 155 seats while PO won 133. The outgoing Prime Minister, Marek Bełka, lost his own seat in the Sejm. In the Senate, PiS won 49 seats and PO 34 of the 100 seats, leaving eight other parties with the remaining 17 seats. Amazingly, the SLD totally collapsed as an independent functioning political grouping and won no seats in the Senate, after having held 75 seats in the previous body. PiS and PO were two center-right political parties that were strongly rooted in the anti-Communist Solidarity trade union movement.28 However, they differed on issues such as budget and taxation matters. The PiS agenda was generally considered more “populist” and included tax breaks and continued state aid for the poor. The PiS pledged to uphold traditional family and Christian values. Many in the PiS leadership voiced skepticism of economic liberalism and of the leadership of Leszek Balcerowicz at the National Bank of Poland. PO was considered as more “business friendly” and promoted the ideals of a “free market.” It supported a flat 15% rate for income, corporation, and VAT taxes. PO also promised to move faster on deregulation of Polish industries, and to foster and hasten privatization and the adoption of the euro, at the earliest possible date.29 Despite a popular belief that these two parties would govern Poland in a coalition, post-election negotiations between PiS and PO concerning the formation of a new government collapsed in late October, precipitated by political disagreements regarding who would become speaker of the Sejm and over the assignment of major ministerial posts in the new government. On 1 November, PiS abandoned coalition talks with PO and instead announced it would act to create a minority government headed by Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz as the new Prime Minister. The delicate negotiations between PO and PiS were further impacted by the 9 October presidential election, in which the PiS standard bearer, Lech Kaczyński, the twin brother of the PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński, defeated Donald Tusk, the candidate of the PO. A minority (coalition) government formed by PiS would be in fact dependent on the support of the radical Samoobrona [Self Defense] and the ultra-conservative League of Polish Families [Liga Polskich Rodzin, or LPR] in order to govern. On 5 May, PiS formed a coalition government with Samoobrona and LPR. However, the political scene remained fraught with petty disagreements, reports of corruption, and general weariness See Federico Bordonaro, “Poland’s Rightward Turn and the Significance for Europe,” Power and Internet News, at www.pin.com/report, January 23, 2008. 28 29 At the time of the 2007 elections, most observers placed the adoption of the euro to be in the year 2012, at the earliest. This prediction seems to have been accurate. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 10 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 on the part of the population with the conduct of some of the major players on the Polish political scene. After more than a year of continued stalemate and further internal squabbling among coalition partners, Marcinkiewicz resigned (or was forced out) as Prime Minister in July of 2006, following reports of a rift with PiS party leader Jarosław Kaczyński. Jarosław Kaczyński subsequently formed a new government and was sworn in as Prime Minister on 14 July 2006—despite having earlier declared that he would not be a candidate should his brother win the Presidency.30 Poland was now “governed by the twins!” The government of Jarosław Kaczyński itself lasted a little more than fifteen months, beset by scandal, charges of obsession with purging ex-Communists from public life, vetting or lustration,31 squabbling, frequent embarrassment, and political infighting verging on internecine warfare with its coalition partners. After the coalition collapsed, early parliamentary elections were scheduled for the fall of 2007. At the conclusion of the 2007 parliamentary campaign, then candidate Tusk signed what have been called the “Ten Commitments” that PO pledged to fulfill during its parliamentary term. These commitments included promises to accelerate Poland’s economic growth, to increase wages in the public sector, to increase pensions and social benefits, to develop the country’s network of highways, to raise the quality of education and improve access to the Internet, and to reform Poland’s healthcare system. Tusk also promised to introduce a flat income tax, to abolish over 200 “administrative fees,” to speed up the construction of stadiums required for “Euro 2112” (the European soccer championships), to encourage Polish émigrés to return home to invest in Poland,32 to conclude Poland’s mission in Iraq, and to take on a “real fight against corruption.” The elections of October 2007 resulted in a decisive victory for PO and the formation of a coalition government between the victorious PO33 with 209 seats and the Radoslaw Markowski, “The Polish elections of 2005: Pure chaos or a restructuring of the party system?” West European Politics, Vol. 29(4), pp. 814-832 (2006). 30 31 According to the Polish Lustration Act, all candidates to the Sejm, Senate or nominees for government posts were to announce whether they collaborated with secret services of the communist regime of Poland. The declaration would then be printed on all official lists of candidates. 32 According to the Polish Information and Investment Agency (PAIiIZ), foreign direct investment (FDI) will fall to zl.37-5-45 billion in 2008 from zl.62.1 in 2007. This reduction is seen as a result of the global economic downturn and may result in an increase of investment in service-based industries and a decrease in production-based investment. Similarly, the Financial Times predicts a drop in FDI from $18 billion to $14 billion in 2009. Thus, a major effort must be maintained to increase non-FDI finance in the Polish financial market. Stefan Wagstyl, “Government pins hopes on consumers,” Financial Times, December 9, 2008, p. 3. The website of the Polish Information and Investment Agency may be accessed at www.paiz.gov.pl. 33 Much of the information concerning Polish political configurations has been adapted from the individual political party websites. Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, PO) wishes to be known as a party in the traditions of a Western European Christian-Democratic Party. In Poland, PO operates as a hybrid “liberal-conservative” political party, combining traditional liberal—essentially free market— stances on economic issues with traditional, conservative stances on many social and ethical issues, including continued opposition to abortion and gay marriage, euthanasia, and fetal stem cell research. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 11 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Polish Peasants’ Party [Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, or PSL] with 31 seats. PO itself took 41.39 percent of the vote (adding 76 seats to its 2005 total) to 32.16 percent for PiS,34 13.2 percent for the Left and Democrats [Lewica i Demokraci, or LiD],35 and 8.93 percent for the PSL. As a result of the elections, a coalition of PO (with 209 seats) and PSL (with 31 seats) formed a government with a working majority in the Sejm. Failing to meet the legally required electoral threshold of five percent were two former PiS coalition partners: Andrzej Lepper’s populist Samoobrona (1.54 percent) and Roman Giertych’s nationalist and ultra-Catholic League of Polish Families (LPR) (1.3 percent). Surprisingly, election turnout was 53.79 percent—the highest percentage of voters in the last six parliamentary elections. In the Senate, PO holds 60 seats and PIS 39, with one seat being occupied by an independent. The new government, under the stewardship of PO, was headed by Donald Tusk,36 who two years earlier had been defeated in his run for the Polish presidency, then gathering 46 percent of the vote in losing to Polish President Lech Kaczyński.37 The While the new government may in fact be as conservative as the prior one, many Polish voters (especially younger voters and those who reside in Warsaw and Krakow) hoped that the PO would at least be more tolerant of opposition views. Prime Minister Tusk’s government was officially appointed by President Kaczynski and sworn in On November 16, 2007. For a discussion of the platform and performance of the PO, see Adam Zdrodowski, “A contentious anniversary,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 17-23, 2008, pp. 8-9. 34 Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) was established in 2001 by the Kaczyński twins, Lech, the current President of Poland, and Jaroslaw, the former Prime Minister. Many PiS members were once closely associated with the now defunct Solidarity Electoral Alliance which operated in the 1990s or with the Movement for the Reconstruction of Poland, under the leadership of the volatile and controversial Leszek Moczulski. 35 Left and Democrats (Lewica i Demokraci) (LiD) is a center-left political coalition in Poland formed by an electoral alliance of political parties in order to compete in the 2007 parliamentary elections. These included: Democratic Left Alliance (SLD); Social Democracy of Poland (SDPL); Labour Union (UP); and Democratic Party (PD). During the 2007 parliamentary elections, the LiD was headed by former President Aleksander Kwaśniewski who announced his “retirement from Polish politics” soon after the disappointing election results were known. 36 For an informative biography of Donald Tusk, outlining his long career as a Solidarity and oppositionist activist, co-founder of the Liberal Democratic Congress (KLD), Deputy Senate Speaker, and since 2001, leader of the PO, see Witold Zygulski, “New Government, Old Conflicts,” Warsaw Voice, November 25, 2007, pp. 6-7. The Economist reported that “Since he won power a year ago, Poland’s Prime Minister, Donald Tusk, has seemed less interested in ruling the country than in preparing for the presidential election in 2010.” “The tough go politicking,” The Economist, December 6, 2008, p. 68. 37 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 12 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 government was comprised of some of the most notable figures in Polish politics: Radosław (Radek) Sikorski as Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jacek Rostowski as Minister of Finance, Zbigniew Ćwiakalski as Minister of Justice, and Bogdan Klich as Minister of Defense. Waldemar Pawlak, long-time head of the PSL, serves as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of the Economy, and Grzegorz Schetyna serves as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Internal Affairs and Administration.38 Sławomir Majman, political columnist for the Warsaw Voice, insightfully commented on the importance of the fall 2007 Parliamentary elections, noting: Poland will be “no more and no less” conservative than before the elections— “only the type and quality of conservatism will change”; Poland has opted for strong and powerful parliamentary government; Poland effectively issued a “red card” to PiS, the winners of the previous election and the party of Poland’s President Lech Kaczyński; PiS will be a powerful voice of opposition in Polish political life; and Poland is essentially a “normal country”—“Poland is a peaceful and stable democracy which can cope very well with its own problems.”39 Financial Times columnists Jan Cienski and Stefan Wagstyl note rather incisively that since 2007, the “confrontation between the two [Kaczynski and Tusk] is, in many ways a fight between two visions of Poland.” President Kaczynski represents the more traditional values of a “conservative, rural and Catholic country,” while Prime Minister Tusk has “become the standard bearer of a younger, more outward looking Poland…. Many have acquired diplomas, often from the numerous private universities, and have migrated from smaller villages to larger cities or abroad.”40 This dichotomy has played out in both support and opposition to the adoption of the euro. 4. The Constitutional Case What many Poles—especially members of the opposition Law and Justice Party conveniently forget—is that Poland, by joining the EU, has already committed itself to join the euro. The conundrum exists as to the mechanism and timing.41 Poland’s Constitution—most especially Article 227—directs that the National 38 For a complete listing of government Ministers in the initial cabinet, see www.premier.gov.pl (last visited January 10, 2009). 39 Slawomir Majman, “The Night After,” Polish Voice, October 28-November 4, 2007, p. 24. Jan Cienski & Stefan Wagstyl, “A tough task ahead for Mr. Tusk,” Financial Times (Poland), December 9, 2008, pp. 1-2. 40 Adapted from Paul Foga, “Euro = Constitutional Amendment,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 17-23, 2008, p. 8. 41 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 13 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Bank of Poland shall have the “exclusive right to issue money” and to “implement monetary policy.” At present, Poland is what is termed, an “honorary” member of the European System of Central Banks. As such, Poland remains free to set its own monetary policy—at least for the time being. However, as a condition of entering the EU, Poland committed itself to satisfying a set of fiscal and microeconomic criteria (The Maastricht Criteria) set by the European Central Bank. These included: Maintaining an inflation rate of no more than 2.3 percent; Maintaining a budget deficit at or below three percent of GDP;42 and Maintaining the level of Polish government debt at no more than 60 percent of GDP.43 At the end of 2007, data indicated that Poland concluded 2007 with an annual inflation rate of 3.5 percent and a budget deficit just below 3 percent, marking a significant improvement from 2005 when Poland’s budget deficit was six percent. According to current planning, at least two years prior to joining the euro-zone, Poland is required to join the exchange rate mechanism called ERM II44 for at least two years before formal adoption of the euro, during which time the fluctuation in the value of the zloty to the euro may not exceed five percent. According to Article 235 of the Polish Constitution, amendments may be proposed by the President, or at least twenty percent of the members of the Polish Parliament or Sejm or of the Polish Senate (Senat). Thus, in order to adopt the euro an amendment to the Polish Constitution, once proposed, must be approved by a two-thirds majority of the Sejm, following which the Senate must approve the amendment by an absolute majority of Senators. In both cases, at least half of the members of both bodies are required to vote. Once the Sejm and the Senate have adopted an amendment, the proposed amendment would be submitted to President Kaczynski for his signature. According to the Constitution, “the President of the Republic shall sign the statute within 21 days of its submission and order its promulgation in the Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland (Dziennik Ustaw).” 42 The Tusk government has forecasted a budget deficit of 2.5 percent for 2008. The European Commission forecasted that Poland’s gross debt is expected to decrease, falling from 44.9 percent of GDP in 2007 to 43 percent of GDP in 2010. For an insightful evaluation of the ability of several of the “ex-communist states” to meet the challenges of the Maastricht Criteria, as well as a critique of these criteria as both “arbitrary,” and “harsh,” see the Economist (on line), “Time to change the rules,” at http://www.economist.com/opinion, December 18, 2008. 43 44 On 31 December 1998, the ECU exchanges rates of the Euro-zone countries were frozen and the value of the euro, which then superseded the ECU at par, was thus established. In 1999, ERM II replaced the original ERM. Thompson Financial News reported that “Poland must enter the pre-euro exchange rate mechanism ERM-2 at latest in the second quarter of 2009 to be ready in 2011 to adopt the common currency….” Dagmar Leszkowicz, “Update 1- Poland c.banker sees ERM-2 at latest in Q2 2009,” at www.forbes.com, September 25, 2008. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 14 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Interestingly, a national referendum may be called by the President, the Sejm, or the Senate within a 45 day period following approval of the proposed amendment by the Senate. However, such a referendum is not required to amend Poland’s Constitution. The issue, thus, is not one of law, but rather one of politics. 5. Arguments on Euro Participation: An Update on the Polish Economy and an Analysis of the “Pro” and “Con” Divide The Economic Backdrop As 2008 comes to a conclusion, several important economic factors have come to the forefront that might impact on Poland’s decision to fully implement its commitment and adopt the euro. Several weeks after President Kaczynski agreed in principle that Poland would join the Eurozone by 2012, the European Central Bank (ECB) came to an agreement with Poland. The ECB would give Poland a 10 billion euro credit line, described as a currency swap agreement, to prevent the further depreciation of the zloty. By December of 2008, the zloty seemed to have stabilized.45 Why has Poland maintained its status as one of the leading transition economies, presumably ready to adopt the euro as its official medium of exchange? Witold Orlowski observed that one of the main drivers of Poland’s successful transition has been its continued ability to attract foreign direct investment. Professor Orlowski notes that the “investment attractiveness” of Poland has been based on the interplay of four solid fundamentals: high labor productivity, moderate labor costs, safety of investments, and good location.46 According to a report issued by the World Bank, Poland is described as “having a robust financial system, a relatively sound banking system, and an overall external debt which is relatively moderate compared to more vulnerable countries.”47 While current indicators do predict a slowdown in the Polish economy—perhaps dropping the growth rate in Poland’s GDP from 5.5 percent to the range of 2.8-3.0 percent in 200948—most observers, however, predict that Poland will be able to avoid a Reported by Stefan Wagstyl, “Lending fears may freeze the system,” Financial Times (Poland), December 9, 2008, p. 6. 45 See Witold Orlowski, “Better placed than neighbors,” Financial Times (Poland), December 9, 2008, p. 6. Mr. Orlowski is the Director of the Warsaw University of Technology [WUT] Business School and serves as an economic adviser to PwC in Poland. 46 World Bank, EU10 Regular Economic Report, reported in Anna Olejarczyk, “Fundamentally sound,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 3-9, 2009, p. 3. 47 The European Commission has chimed in with its predictions for Poland’s GDP growth, asserting that “Domestic demand will continue to be the main driving force of GDP growth, which is expected to fall to 3.8 percent in 2009 and 4.2 percent in 2010.” See European Commission, Economic Forecast Autumn 2008, reported in E. Blake Berry, “An island of relative calm,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 1016, 2008, p. 5. For a discussion of Poland’s economic prospects in 2009, see Economist Intelligence Unit, “The World in 2009” (Poland), January 2009, p. 115. The Economist predicts GDP growth of 3.8%; an 48 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 15 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 serious recession in 2009 and 2010, continuing the “remarkable recession-free run that began in 1992.”49 However, several potential negative factors loom on the horizon: turbulence and uncertainty in foreign exchange, a negative credit outlook for the Polish banking system that might result in an increase in credit costs by 2-3 percentage points, a property slump, falling government revenues, and a slowdown in the export-oriented car sector. On the positive side, Prime Minister Tusk was successful in enacting several bills through parliament which were aimed at reducing bureaucracy and reforming what most observers noted was a “dysfunctional pension system.”50 In addition, according to official government estimates, the Polish economy “will expand in the first year of membership in the euro zone by 0.23-0.58 percentage point, while in the fifth year—by 0.42-1.65 percentage points.”51 The Euro Debate: Economic and Monetary “Pros” and “Cons” There are varied opinions on the issue of whether Poland’s economy is actually prepared for adoption of the euro. Professor Janusz Bilski of the University of Lodz has summarized some of the main arguments against the adoption of the euro.52 These include: A worldwide financial crisis and a recession will stop economic growth for the next two to three years, ushering in a period of “soft economic nationalism” at the expense of “mechanisms and regulations of monetary unions.” It is unrealistic to impose severe restrictions on the Polish economy amid the crisis. The next two to three year period (2009-2011) may be the “worst possible timing for the euro adoption since the moment of creating the euro zone.” Only a monetary policy run by Polish national authorities can effectively protect Poland’s poor and its pensioners against economic recession in an environment in which the unemployment rate could once again rise from 7.8% in 2008 to 9.9% in 2009. The decision of “fast euro adoption” will add an external burden on inflation rate of 3.8%; and a GDP per capita of $14,640—in PPP, $18,980. 49 Cienski & Wagstyl, supra note 40, at 1. 50 The Associated Press reported that Polish lawmakers had overturned a veto by President Kaczynski of a bill that would reduce sharply the numbers eligible for early retirement to around 240,000 from more than one million. The new law removes the right to an early retirement from about 750,000 workers. Generous provisions for early retirements were seen as a vestige of the communist, “full employment,” era. See Associated Press, “Polish parliament overturns a presidential veto, passes law cutting early retirement,” at http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/sns-ap-eu-poland-early-retirement, December 22, 2008. “Has Poland Chosen Worst Timing Even for Euro Adoption?” Polish News Bulletin (on line), December 12, 2008, citing Rzeczpospolita, December 11, 2008, p. B12. 51 52 Arguments for and against the adoption of the euro have been adapted and extrapolated from id. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 16 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 economic policy “exactly at a time when it should be as flexible as possible.” The adoption of the European Central Bank’s interest rate may hurt the Polish economy. In contrast to an emerging trend, “the government’s aim seems to be to keep fiscal policy tight so that the central bank can cut interest rates.”53 Restrictions adopted by many countries against worker migration and the provision of services by Poles may distort the effect of any adjustment mechanisms adopted by the EU. On the other side of the equation, Professor Bilski notes some potential positive benefits from the adoption of the euro. These include: Adoption of the euro might be a spur to Poland’s attempt to reform its public finance system and in its efforts to tame or control inflation. The decision to adopt the euro “may be [one] of the country’s most vital decisions in the next decade as it is likely to ensure good conditions for stronger economic growth.” For the Polish economy—which Professor Bilski terms as a “peripheral economy—the adoption of the euro will be beneficial if it is a part of a plan “ensuring better implementation of [Poland’s] strategic economic goals.” In addition, the World Bank has noted that the Polish plan to adopt the euro in 2012 is an important step in the further development of Poland’s financial environment. According to Thomas Laurson, country manager at the World Bank for Poland and the Baltic States, “Poland is really the only country now in the region that has a firm and, at least as far as possible, a credible plan for adopting the euro.”54 6. Some Tentative Conclusions Both proponents and opponents of euro adoption agree that the decision to join the Euro-Zone will have lasting implications for the Polish economy, and by implication, for Polish society. Poland’s economy, while generally robust and growing, albeit at reduced growth rates, is still not fully developed. Poland has many microeconomic economic issues to tackle within the context of maintaining reasonable economic growth, so as to create a climate in which it can face and meet the expected competition from some of the world’s leading economies. Even an opponent of euro adoption, Professor Jan Bilski, is most aware of the core importance of speedy euro adoption.55 In sum, the arguments boil down to a fundamental disagreement whether the adoption of the euro 53 “The tough go politicking,” supra note 37. 54 Anna Olejarczyk, supra note 47. 55 Rzeczpospolita, supra note 51. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 17 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 will amount to a “risky economic experiment” that will lead Poland into a prolonged recession in which the European Central Bank’s interest rates might hurt the Polish economy. It thus appears to all that an important interim step will be Poland’s joining the ERM-2 during which it must stabilize the zloty-to-euro exchange rate and create suitable adjustment mechanisms. Rzeczpospolita reports that in contemplation of this event, “Narrowed margins for currency rate volatility are likely to lay new ground for Polish economy functioning and it should be carefully monitored how the market reacts to asymmetric shocks as well as what are the cost of their absorption.”56 It appears to many observers that the decision to adopt the euro has now been made. Questions remain are how and when. Both opponents and proponents agree that the adoption of the euro will impose some restrictions on the ability of the National Bank of Poland to direct Poland’s monetary policy. The real question is when Poland should take this dramatic step. Given the competing viewpoints, the position of the Prime Minister may, in fact, be most correct: “The main obstacle to the carrying out of the plan [to adopt the euro by 2012] according to Donald Tusk, may be the lack of political consensus rather than the condition of Poland’s economy, which is fairly stable.”57 REFERENCES Associated Press. (2008). “Polish parliament overturns a presidential veto, passes law cutting early retirement,” at http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/sns-ap-eu-polandearly-retirement, December 22. Axelrod, Toby. (2004). “Polish Holocaust survivors press on with restitution claims,” at http://www.jta.org.html, April 7. BBC News. (2008). “Poland may get referendum on euro,” October 28, 2008, at http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk. Berry, E. Blake. (2008). “An island of relative calm,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 10-16, 2008, p. 5. Bordonaro, Federico. (2008). “Poland’s Rightward Turn and the Significance for Europe,” Power and Internet News, at www.pin.com/report, January 23. Brands, H.W. (2008). Traitor to His Class, pp. pp. 800-803. Chodakiewicz, Marek Jan & Dan Currell. (2003). “Restyytucja: The Problems of Property Restitution in Poland (1939-2001),” in Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, John 56 Id. Polish News Bulletin, “PM and Finance Minister on Euro,” December 9, 2008, citing Gazeta, December 10, 2008. 57 June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 18 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Radzilowski & Dariusz Tolczyk, eds., Poland's Transformation: A Work in Progress, pp. 157-193 (2003). Cienski, Jan & Stefan Wagstyl. (2008). “A tough task ahead for Mr. Tusk,” Financial Times (Poland), December 9, pp. 1-2. CNN.com. (2008). “Slovakia hopes euro move brings stability,” December 31. Commission on the European Communities. (2002). “2002 Regular Report on Poland’s Progress Toward Accession,” Brussels, October 9. Czop, John. (2008). “The Euro and Poland’s Security,” The Post Eagle (Clifton, N.J.), December 10, p. 2. DJ News. (2008). “Court Rejects German Compensation Claims Against Poland,” www.djnews.plus.com, October 10. Dougherty, Carter. (2008). “Some Nations That Spurned the Euro Reconsider,” New York Times (on line), at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/02/business/worldbusiness/o2euro.html, December 2. Economist. (2008). “The tough go politicking,” December 6, p. 68. Economist (on line). (2008). “Time to change the rules,” at http://www.economist.com/opinion, December 18. European Commission. (2000). “Report on the European Commission’s Reform,” March. European Council. (2003). “Conclusions of the Presidency,” Copenhagen, 21-23 June 1993, SN/180/93, p. 13, adapted from “Enlargement,” at http://europa.eu.int/comm/ enlargement/enlargement.htm. Foga, Paul. (2008). “Euro = Constitutional Amendment,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 17-23, p. 8. Griffith, Joan. (2008). Reprivatization: Claiming Family Property in Poland, at http://www.polishclaims.com/homepage.html. Hunter, Richard J., Jr., Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V. & Robert E. Shapiro. (2003). Poland: A Transitional Analysis, pp. 125-145. Hunter, Richard J., Jr. & Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V. (2005). “A Primer on the National Bank of Poland: A Central Institution in the Transformation Process,” European Journal of Economics, Finance, and Administrative Sciences (on line), Vol. 1, No. 1. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 19 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Hunter, Richard J. & Leo V. Ryan. (2008). "A Field Report on the Background and Processes of Privatization in Poland," Global Economy Journal, Vol. 8, Iss. 1, Article 5, at: http://www.bepress.com/gej/vol8/iss1/5. Hunter, Richard J., Jr. & Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V. (2008). “The Ten Most Important Economic and Political Events Since the Onset of the Transition in Post-Communist Poland,” The Polish Review, Vol. LIII (2), pp. 183-216, 203-209. Hunter, Richard J., Jr. & Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V. (2008). “An Update on the Polish Economy: Meeting the Criteria for a ‘Normal Country,’” European Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 375-381. International Herald Tribune. (2009). “Economic sentiment plunges in euro zone,” citing Reuters, at http://www.iht.com/articles/2009/01/08/business/euecon.php, January 8, 2009. Kaczorowska, Malgorzata. (2002). “EU Negotiations: Milking an Issue,” Warsaw Voice, December 15, p. 5. Kaczorowska, Malgorzata. (2002). “Triumph of the Will,” Polish Voice, December 2229, pp. 7-8. Leszkowicz, Dagmar. (2008). “Update 1- Poland c.banker sees ERM-2 at latest in Q2 2009,” at www.Forbes.com, September 25. Majman, Slawomir. (2007). “The Night After,” Polish Voice, October 28-November 4, p. 24. Markowski, Radoslaw. (2006). “The Polish elections of 2005: Pure chaos or a restructuring of the party system?” West European Politics, Vol. 29(4), pp. 814-832. Mason, D.S. (1992). Revolution in East Central Europe, p. 40. Moore, Matt & George Frey (2008). “Euro currency turns 10: seen fulfilling promise,” Aruba Today, citing the Associated Press, December 29, p. B8. Narayanswany, Ramnath. (1988). “Poland: The Reform That Never Was,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 23, No. 16, April 16, pp. 778-779. Orlowski, Witold. (2008). “Better placed than neighbors,” Financial Times (Poland), December 9, p. 6. O’Rourke, Breffni. (2003). “Poland After EU Vote, Poles Wonder Where They Go From Here,” at http://www.rferl.org/nca/features, June 9. Polish News Bulletin. (2008), “PM and Finance Minister on Euro,” quoting Gazeta, December 9. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 20 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Polish News Bulletin. (2008). “Has Poland Chosen Worst Timing Even for Euro Adoption?” December 12, citing Rzeczpospolita, December 11, 2008, p. B12. Polish Voice. (2003). “Serving a More Perfect Union,” No. 34, July 31, pp. 15, 17. Polonia Today. (2003). “Kwaśniewski Ratifies Poland’s EU Vote,” August, p. 12. Transition. (2000). “Milestones of Transition,” Vol. 11, No. 1, February, pp. 16, 31 Slater, Joanna & Joellen Perry. (2008) “On Euro’s 10th Birthday, No Music,” Wall Street Journal, December 16, p. C1. Wagstyl, Stefan, John Reed & Christopher Bobinski. (2007). “The Long March Towards Union with Europe,” Financial Times, April 17, p. I. Wagstyl, Stefan. (2008). “Government pins hopes on consumers,” Financial Times, December 9, p. 3. Wagstyl, Stefan. (2008). “Lending fears may freeze the system,” Financial Times (Poland), December 9, p. 6. Weschler, Lawrence. (1982). Solidarity: Poland in the Season of Its Passion, p. 46. World Bank (2008). EU10 Regular Economic Report, reported in Anna Olejarczyk, “Fundamentally sound,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 3-9, p. 3. Zamojski, Marcin. (2008). “Six billion Euro for reprivatization,” at www.news.Poland.com, September 22. Zdrodowski, Adam. (2008). “A contentious anniversary,” Warsaw Business Journal, November 17-23, pp. 8-9. Zygulski, Witold. (2007). “New Government, Old Conflicts,” Warsaw Voice, November 25, pp. 6-7. APPENDIX “The Path to the Euro” STAGE 1: Oct.-Dec. 2008: June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 21 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Finance Ministry and the central bank make preliminary preparations for negotiating Poland’s entry in the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM-2) Nov. 2008: Appointment of government official to coordinate euro adoption process and inter-institutional working groups Dec. 2008: Publication of central bank’s report on Poland’s euro zone membership Q 1 2009: Starting procedures to change Poland’s Constitution 2009: Finance Ministry and central bank hold negotiations with EU institutions on Poland’s ERM-2 entry STAGE 2: 2009: Poland to join ERM-2 2009: Start of the public information campaign on the euro 2009: Decision on symbols for Poland’s euro coins 2010: Preparing legal acts for euro adoption May-June 2011: Poland’s procedures evaluated by various EU institutions Mid-2011: Ecofin (The Economic and Financial Affairs Council) decision to lift Poland’s derogation clause (permitting Poland to suspend certain rights in narrowly determined situations, particularly situations involving a public emergency) Mid-2011: Ecofin decision concerning setting the irrevocable conversion rate of the euro to the zloty STAGE 3: By end of 2011: Production of euro coins After conversion rate set: Start of dual display of prices and monitoring of price practices in the retail and banking sectors Dec. 2011: Sales of “starter kits” to small companies and “mini kits” to citizens Dec. 2011: Preparation of cash machines and payment terminals to switch to the euro Quarter 4 2011: Final stage of IT and accounting systems convergence to the euro June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 22 2009 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-1 Quarter 4 2011: Information and media campaign about practical aspects of euro adoption STAGE 4: Jan. 1, 2012: Poland joins the euro zone. Euro notes and coins enter into public circulation TBD: Dual circulation period After the dual circulation period: Zloty stripped of official currency status—euro becomes the only official currency in Poland TBD: Free zloty-to-euro exchange at banks SOURCE: “Poland unveils plan to adopt euro as its currency by 2012,” Irish Times, as reported by Reuters, October 29, 2008, at http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/finance/2008/1029/12251972731198.html. June 24-26, 2009 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 23