QuebecDisasterReport Group 13.doc

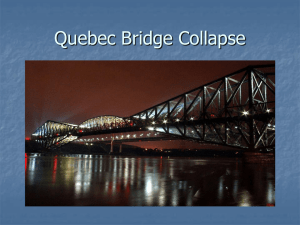

advertisement

What Happened & What Were the Consequences? The Quebec Bridge collapsed on the 29th of August 1907. Designed to be the longest spanning bridge of its time, it was to span 1800 feet across the St Laurence River a few km from Quebec City. The bridge was designed as a cantilever bridge i.e. a continuous beam anchored at both ends by pillars. On the 17th of June, during the construction of the south anchor, difficulties were noted in riveting the bottom chord splices due to deformation of the faced ends of the middle ribs. These deformations were ignored and construction continued. The central, suspended span began to be constructed in July. By early august the end details of the lower compression chords began to show signs of buckling. By august 6th two of the lower chords of the south arm cantilever were bent (7-L and 8-L). By the 12th of August the splice between lower chords 8-L and 9-L was also bent. On the morning of the 27th two days preceding the collapse the chord 9-L of the south anchor arm, which had showed a deflection of .75 of an inch only a week before, showed a deflection of 2.25 inches. On the 29th of August two of the compression chords on the south anchor arm suddenly failed. This failure spread through the entire south anchor of the bridge to the south cantilever (weighing 19000 tonnes together) and finally to the partially constructed central span of the bridge. Within 15 minutes the entire superstructure had collapsed into the river beneath. The Design: The design of the bridge was quite a difficult one due its location. As the St Laurence was a shipping lane the Quebec Bridge required a single span of 1600 feet and height above the river of 150 feet. This coupled with the 67 foot width required to accommodate railway tracks, streetcar tracks and two roadways led to a particularly large and heavy central span. In the case of any cantilever bridge the weight of the central span is key to the design. Steel plate cylinders were to be used as the main compression members. These were to be prefabricated off site. What Were the Technical Factors Contributing to the Disaster? Early on in the design the chief engineer, Cooper, recommended that the span be increased to 1800 feet to speed up construction and prevent piers being subject to heavy ice flows during winter. This decision coupled with modified specifications allowed for higher unit stresses. These were later almost ignored in design considerations. The main factor responsible for the failure however was an incorrect initial calculation of the weight of the bridge, which was discovered only after commencement of construction. Construction was started assuming the initial estimated weights were correct. The bridges actual weight was almost 8 million pounds greater then the design value. It was decided that this excess weight was catered for in the safety tolerances. During the construction phase inadequate riveting of some of the bridges key weight bearing lower chord members in the south anchor left some key elements unstable. This was at least partially due to lack of understanding of the instability of latticed compress ional members during construction, i.e. asymmetries during construction lead to increased likelihood of failure. Finally the lack of action taken when deformations far exceeded expected values was a big contributor to the final disaster. Human & Managerial Factors Contributing to the Disaster: Theodore Cooper, a leading bridge engineer at the time was appointed as chief consulting engineer for the Quebec Bridge Company in 1900. He had signalled that the Quebec Bridge would be his final project, the pinnacle of a long and distinguished career. Pride in this project inhibited the appointment of a second consultant engineer to review technical aspects of the design and in particular the high unit stresses in the bridge members. This was suggested at the time by Collingwood Schreiber of the Department of Railways and Canals. The appointment Phoenix Bridge Company has been questioned since the disaster. It is evident from communication between Phoenix and the Quebec bridge company that pressure was brought to bear on Theodore Cooper, the consultant engineer, to accept their tender. When time for construction finally arrived, no tests had been done to revise the weights under the new specifications drawn up by Cooper to compensate for the increased bridge length. Work went ahead using outdated assumed weights. Cooper did not intervene, he accepted the theoretical figures provided by the Phoenix Bridge Company. Construction went ahead using proposal drawings only. These were approximations and the design was as yet incomplete. During construction the Chief Consulting Engineer, Cooper, never actually visited the construction sight. He instead appointed a recently graduated inexperienced engineer, Norman McLure, to oversee the construction, while he worked out of Manhattan. The distances involved made communications slow in an emergency such as major deflections in the bottom compression chords of the south anchor.