From Expressive to Transactional Writing: A “Walk-Through” Exercise Randall Martoccia Department of English

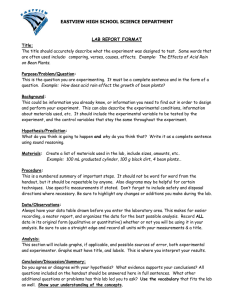

advertisement

From Expressive to Transactional Writing: A “Walk-Through” Exercise Randall Martoccia Department of English Among the many writing problems students confront, one of the most common is a poor concept of paper structure. Students are often aware of their problems with structure but have received little instruction in organizing—aside from high-school lessons on the five-paragraph essay. By the way, college teachers tend to despise blind adherence to this form, believing it does to thought what the bonsai technique does to trees. Most college students find out early in their college career how little use the five-paragraph form is when dealing with more complex papers. In a poll I conducted just before a paper deadline last year, students voted that “paper structure” was their area of greatest concern. “Paper structure” even edged out “writing concisely” and “avoiding plagiarism.” Poor conception of structure manifests itself in many ways: paragraphs are wildly unfocused, having a different topic in each sentence; introductory material shows up too late; and related information winds up in different paragraphs. One especially nagging problem is the tendency of writers of research papers to organize their essays according to sources rather than topics. The exercise described here addresses this organizational problem. When conducting research in preparation for writing research papers, students often become overwhelmed with the information they find. Many of them also procrastinate, leaving themselves no choice but to skip steps in the writing process. Skipping the planning and organizational steps of the process can be crippling for students. The problem I mentioned earlier—structuring according to sources not topics—is a result of students missing the step between note-taking and drafting. Using an exercise that simulates this step—call it the categorizing of information—can be an effective way to address the problems caused by lack of thoughtful categorizing. This categorizing activity addresses what John C. Bean calls Data Dump writing. Here Bean describes this kind of writing: “Data dump writing […] has no discernable structure. It reveals a student overwhelmed with information and uncertain what to do with it” (23). While one could argue that papers organized according to sources do have a kind of structure to them, “dumping” seems a suitable label for this kind of writing since it ignores the conceptual relationships between ideas. According to Bean, Jean Piaget would likely consider source-structured writing a result of concrete-operational reasoning. Students who reason in this way may be able to organize information in simplistic ways, but they tend not to think abstractly (Bean 24-25). Other students who might be able to recognize the underlying relationships between ideas in their research do not always give themselves the opportunity to so. Technology enables students to cut-and-paste information straight from a source into their paper. By doing so, students skip the note-taking step in the research-paper process. “By not taking notes,” Bean writes, “students are less apt to reflect on their reading or make decisions in advance about what is or is not important” (204). Moreover, the note-taking and the categorizing stages work together to reveal what is or is not related. When these steps are skipped and similarities are ignored, superficially related ideas may end up in the same paragraph while more closely related ideas may be at opposite ends of the paper. 2 The activity described below is meant to simulate the categorizing step in the writing process that immediately follows note-taking—but is often passed over due to students’ increased use of technology. The handout consists of paraphrases and quotations from an actual paper. I essentially disassembled an MLA-formatted paper and re-sorted the information according to the sources. In the paper, of course, the information was arranged according to topics. The purpose of presenting the information organized by source is to present students with a mass of facts, quotations, and ideas—a clump of material similar to what they soon will be dealing with as their research progresses. At some point their notes will be organized according to sources. Here’s the handout: _____________ Pretend that below are the notes you’ve taken—including paraphrases and quotations— while researching your paper. Currently the info is in the order you’ve found it. Your job today is to categorize the information according to topics and sub-topics. On Thanksgiving weekend in 1999, John and Carole Hall were killed when a Naval midshipman crashed into their parked car (Stockwell B8). The driver said, “When I looked up from the cell phone I was dialing, I was three feet from the car and had no time to stop” (qtd. in Stockwell B8) _______________________________ The midshipman was charged with vehicular manslaughter for deaths of John and Carole Hall (Layton C1). The judge was unable to issue a guilty verdict. He found the defendant guilty of negligent driving and imposed a $500 fine (Layton C1) Two years after the accident, the county where the accident happened passed a law forbidding cell phone use while driving (Layton C2) State legislators are beginning to receive public pressure to pass anti-cell-phone laws. “It’s definitely an issue that is gaining steam around the country,” says Matt Sundeen of the National Conference of State Legislatures (qtd. in Layton C9). The first town to restrict use of handheld phones was Brooklyn, Ohio (Layton C9). Frances Bents, an expert on the relation between cell phones and accidents, estimates that between 450 and 1,000 crashes a year have some connection to cell phone use (Layton C9). _______________________________ In Georgia, a young woman distracted by her cell phone ran down and killed a two-yearold. Her sentence was ninety days in boot camp and five hundred hours of community service (Ippolito J1). _______________________________ 3 A New England Journal of Medicine study concluded that a driver using a cell phone was four times as likely to get into a collision as a driver not using a cell phone (Redelmeier and Tibshirani 456) _______________________________ On November 7, 1999, two-year-old Morgan Pena was killed by a driver distracted by his cell phone (Besthoff). On November 14, 1999 corrections officer Shannon Smith was killed by a woman distracted by her cell phone (Besthoff). _______________________________ John Violanti of the Rochester Institute of Technology found a nine fold increase in the risk of a fatality if a phone was being used and a doubled risk simply when a phone was present in a vehicle (522-523). _______________________________ In a survey done by Farmers Insurance Group, 87% of those polled said that cell phones affect a driver’s ability, and 40% reported having close calls with drivers distracted by phones. Lon Anderson of the American Automobile Association asserts, “In many states, there is momentum building to pass laws” (qtd. in Farmer Insurance Group). ______________________________ Morgan’s mother, Patti Pena, reports that the driver “ran a stop sign at 45 mph, broadsided my vehicle and killed Morgan as she sat in her car seat. The driver who killed Morgan Lee Pena received two tickets and a $50 fine and retained his driving privileges (Pena). _______________________________ In Suffolk County, New York, it is illegal for drivers to use a handheld phone for anything but an emergency call (Haughney A8). _______________________________ As of December 2000, twenty countries were restricting use of cell phones in moving vehicles (Sundeen 8). _______________________________ Currently, no state has a law forbidding people from using cell phones while driving (Smith 7). ****** The exercise consists of three parts: (1) First, students find and group similar information. They are asked to identify the paper’s topics. This part takes 15-20 minutes. Each student works alone. (2) Next, I stand in front of the board and ask the students to list the topics one by one. Volunteers call these topics out to me, and I write them down. We also identify the different items from the handout that belong under each topic. 4 (3) I then ask them to consider what would be the most logical order for these topics. We discuss the potential strengths and weaknesses of different ways of putting the paper together. The paper from which these notes were pulled is in Diana Hacker’s The Bedford Handbook—the textbook my students use. After the exercise is over, I invite students to read the original paper and compare their reassembled version to it. You can find the paper online at http://bcs.bedfordstmartins.com/bedhandbook7enew/Player/Pages/Frameset.aspx. An admitted limitation of this assignment is the amount of class time it requires. While the nature of composition classes allows much time to different stages of the writing process, a teacher of a typical writing-intensive class likely does not have such a luxury. Also, the handout may not address each professor’s most pressing areas of concern related to writing. However, one can easily modify the assignment by disassembling a more applicable paper and crafting the activity to meet those concerns. Many aspects of the writing process—such as, sentence construction and paragraph development—can be simulated in a disassemble/reassemble kind of exercise. “Walk-through” activities can be used in relation to any writing assignment. Bean describes these activities in Chapter 12 of Engaging Ideas (specifically, on 213-4). In these kinds of activities, students are exposed to the situations that they’ll be going through in their own papers. Simulations and “walk-throughs” have such great potential because students get to practice without the pressure of being graded. References Bean, J. C. (2001). Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.