The Bureaucracy.doc

advertisement

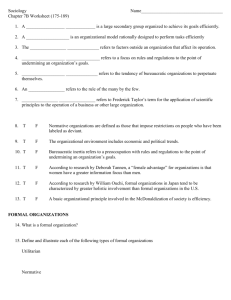

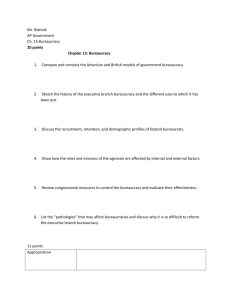

Lecture – The Bureaucracy 1. Bureaucracy and Bureaucrats. Bureacracies provide coordination, organization, specialization, and expertise for government to perform tasks and services. Therefore, a bureaucracy is defined as the complex structure of offices, tasks, rules, and principles of organization that are employed by all large-scale institutions to coordinate the work of their personnel. Each bureaucratic office has a set of tasks to perform and individuals assigned to perform those specialized tasks. These tasks may be routine or they may be politically charged; bureaucracies can, in some cases, make important government policy. A. The Size of the Federal Service. The size of the federal service has actually declined over the past two and a half decades. The number of civilian federal employees was approximately 2.7 million in 2008, compared to 3.0 million in 1968. In fact, the proportion of the U.S. workforce that works for the federal government has not risen in over fifty years. Bureaucracies are commonplace – they touch many aspects of daily life. B. Bureaucrats. Specialized bureaucrats rely on complex information networks to connect each cog in the bureaucratic machine to the others. C. What Do Bureaucrats Do? Congress makes laws, but the legislation passed by Congress typically provides only general guidelines. It is up to the bureaucracy to “fill in the blanks” of these general dictates and translate those broad guidelines into concrete action through implementation, enforcement, rule making, and adjudication. Implementation is defined as the efforts of departments and agencies to translate laws into specific bureaucratic rules and actions. When laws passed by Congress are particularly vague, bureaucrats have broader latitude in how to interpret those laws. Congress may grant an agency authority to engage in rule making (a quasilegislative administrative process that produces regulations by government agencies) and/or administrative adjudication (applying rules and precedents to specific cases to settle disputes with regulated parties). Bureaucratic agencies are also sometimes given enforcement power, power to investigate violations of the law and possibly impose sanctions on those who do not obey. Government and private bureaucrats do essentially the same thing. However, the public perception of less efficiency in public agencies is due to political, judicial, legal, and public opinion restraints and high expectations imposed on public bureaucrats. D. The Merit System: How to Become a Bureaucrat. Public bureaucrats enjoy more job security than do their private counterparts. In an effort to eliminate the spoils system, the federal government adopted a merit system for the bureaucracy: bureaucratic employees should be hired based on qualifications (rather than as a reward to partisan support) and can only be fired for poor job performance. 2. The Organization of the Executive Branch. Cabinet departments (the largest sub unit of the executive branch, in which the heads of the fifteen departments in the Cabinet are called secretaries), agencies, and bureaus are the operating bureaucratic units. Not all government agencies are part of the Cabinet departments. Some independent agencies (agencies that are not part of a Cabinet department) are set outside the departmental structure, such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) or the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The government corporation, a third type of agency, is an agency that operates more like a private business, providing a good or service in exchange for a fee (for example, the U.S. Postal Service or Amtrak). A fourth type of agency is the independent regulatory commission, such as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Federal Communication Commission (FCC), gives broad discretion to make rules. The different agencies of the executive branch can be classified into groups by the type of services they provide to the American public: 1. Promotion of the public welfare. 2. Promotion of national security. 3. Promotion of a strong economy. A. Promoting the Public Welfare. The bureaucracy promotes the public’s welfare by enhancing or protecting the general well being. These agencies provide services, build infrastructure, and enact regulations designed to enhance the well being of the vast majority of citizens. How Do Federal Bureaucracies Promote the Public Welfare? They do so with a diverse set of services, products, and regulations. For example, DHHS administers the programs that come closest to the general understanding of welfare – Temporary Assistance to Needy Families and Medicaid (providing health care for low income families), and Medicare (health insurance for the senior population). Another example is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a regulatory agency (a department, bureau, or independent agency whose primary mission is to impose limits, restrictions, or other obligations on the conduct of individuals or companies in the private sector) that works to protect the American public by setting food standards. Bureaucracies, Clienteles, and the Public. Some public agencies providing services are tied to a specific segment of the American population that is often thought of as the main agency clientele. For example, the Department of Agriculture promotes the interests of farmers. These relationships with a particular clientele protect agencies from political attack, because the clientele can be mobilized to resist threats to the agency that provides them services. The stable, cooperative relationship that often develops among an administrative agency, the congressional committee or subcommittee with oversight of the agency, and one or more organized groups of clientele is often described as an iron triangle. Clientele do not automatically get their way with their agencies, as the agencies have to balance scarce resources and competing demands. Moreover, agencies are scarce resources and competing demands. Moreover, agencies are increasingly seeking support from the public more generally. B. Providing National Security. Vital agencies providing security for the United States are mostly located in state and local governments – such as the policy. There are also national security agencies, including two groups: 1. Control agencies for defense against internal security threats. 2. Security agencies for defense against external threats. Agencies for Internal Security. Domestic security tasks changed drastically after 9/11. Prior to 9/11, most national security efforts went into prosecuting federal crimes, and the Department of Justice was charged with this task. However, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the DOJ reoriented its activities, aided by the USA PATRIOT Act, which gave broad powers to the DOJ to detain foreigners suspected of posing a threat. In the wake of 9/11, the federal government also created the Department of Homeland Security, signaling the high priority domestic security has. Since 2002, DHS joined DOJ in domestic security efforts. However, the combined efforts brought disputes over the responsibilities of the two departments. The response to Hurricane Katrina illustrated the continuing problems DHS faced in combining diverse agencies under its auspicies. Agencies for External National Security. External national security is maintained by the Department of State and Department of Defense. The State Department’s primary mission is diplomacy. It also supports the responsibilities of the foreign service officers who staff American embassies abroad. DoD’s original purpose was to unify the military departments into one national security establishment, but this did not occur. The DoD is organized according to a chain of command. At the top of the chain are the chiefs of staff – collectively, the Joints Chiefs of Staff – who direct military policy and management. In 2002, the Defense Department created the first command charged with homeland defense and domestic military operations, the U.S. Northern Command. The 9/11 Commission’s work prompted a major reorganization of the fragmented intelligence community, including creation of a new director of national intelligence. National Security and Democracy. Agencies charged with securing the nation often come into conflict with Americans’ expectations of democracy. The two major issues are: 1. The trade offs between respecting the personal rights of individuals versus protecting the general and public. 2. The need for secrecy in national security matters versus the public’s right to know what the government s doing. C. Maintaining a Strong Economy. The government does not run the American economy. However, it conducts activities critical to maintain a strong economy. Fiscal and Monetary Agencies. Government activity relating to public finance is called fiscal policy. In the United States, we generally use the term fiscal policy to refer to government taxation and spending, and we use the term monetary policy to refer to policies about banks, credit, and currency. The Treasury Department administers fiscal policy. It collects income, corporate, and other taxes; prints currency; and manages the large national debit ($17.4 trillion as of 2013). Another important fiscal (or monterary) agency is the Federal Reserve System, a system of twelve banks that facilitates cash exchange, checks, and credit; regulates member banks; and uses monetary policies to fight inflation and deflation. It has authority over the interest rates and lending activities of the nations’ most important banks. Revenue Agencies. These agencies are responsible for tax collection. Examples include the Internal Revenue Service for income taxes; the U.S. Customs Service for tariffs and other taxes on imported goods; and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms for the collection of taxes on the sales of those particular products. Economic Development Agencies. These federal agencies are charged with conducting federal programs designed to strengthen particular economic segments. For example, the Department of Agriculture helps advance the American economy by supporting our farmers. 3. Can Bureaucracy Be Reformed? When citizens complain about bureaucracy, they mean it is inefficient and wasteful. For example, DoD revealed it once $435 apiece for hammers. Bureaucracy came to be synonymous with mountains of pointless paperwork, long wait times, and poor results. Efforts to improve bureaucratic performance take two general approaches: Democratic administrations generally try to make existing bureaucracies work better, while Republican administrations generally try to reduce the number of agencies and the size of the bureaucracy. A. Reinventing the Bureaucracy. President Bill Clinton put Vice President Al Gore in charge of his mission to make government more efficient, accountable, and effective. Clinton’s efforts did reduce costs and the overall size of the federal workforce, but it did not provide the sort of sweeping reform some leaders wanted. B. Termination. This downsizing method entails the elimination of programs; however, once you start talking about getting rid of particular programs, the people who benefit from those programs mobilize. Another approach is to thwart unpopular regulatory agencies by deregulation, reducing or eliminating regulatory restraints on the conduct of individuals or private institutions so there is less for bureaucratic agencies to do. C. Devolution. The next best approach to reducing bureaucracy is devolution. Devolution is a policy to remove a program from one level of government by delegating it or passing it down to a lower level of government, such as from the national government to state and local governments. Devolution can cause problems because: a. States cannot generally run deficits, so poorer states have difficulty implementing effective policies. b. Devolution may exacerbate inequalities, both social and economic. One benefit of devolution – the ability to create more flexible programs – is also a drawback, as it means there is more variation (and hence less equality) in program benefits. D. Privatization. This other downsizing effort entails moving all or part of a program from the public sector to the private sector. Most of what is called privatization is the provision of government goods and services by private contractors under direct government supervision. Theoretically, privatization encourages efficiency, but many services government provides are inconsistent with a profit motive. 4. Managing the Bureaucracy. Bureaucracies provide the expertise needed to implement the public will but they can also become entrenched organizations that serve their own interests. The problem to solve is how to take advantage of bureaucratic benefits while keeping bureaucracy accountable. Accountability implies a higher authority checking and judging bureaucratic action, the highest authority being the people. A. The President as Chief Executive. Under Franklin D. Roosevelt, three management policies were adopted to “help” the president oversee the bureaucracy. a. All executive policy decisions must pass through the White House. b. In order to cope with information, the White House must have adequate staff in research, analysis, legislative and legal writing, and public affairs. c. The White House must have additional staff to follow through on presidential decision. B. Making the Managerial Presidency. Each expansion of the national government into new policies and programs in the 20th century was accompanied by a parallel expansion of the president’s management authority, resulting in the “managerial presidency.” Bureaucratic reform does not necessarily ensure democratic accountability, and presidents may use their managerial capacities to limit accountability if they think it is a hindrance to effective government. Executive privilege is the claim that confidential communications between a president and close advisers should not be revealed without the consent of the president. 5. Congressional Oversight. Ultimately, the key to bureaucratic responsibility is congressional legislation. When Congress enacts vague legislation, agencies must resort to their own interpretations. The president and the federal courts, as well as interest groups, often step in to tell agencies what the legislation intended. This creates confusion about to whom and to what the agency is accountable. Oversight is the effort by Congress, through hearings, investigations, and other techniques, to exercise control over the activities of executive agencies.