Document 15450003

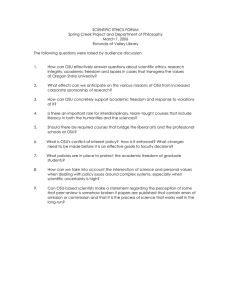

advertisement