Who is easier to nudge? John Beshears James J. Choi David Laibson

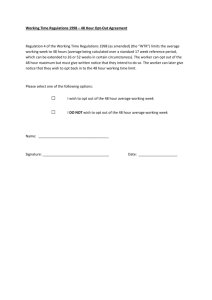

advertisement

Who is easier to nudge? John Beshears James J. Choi David Laibson Brigitte C. Madrian Sean (Yixiang) Wang The appeal of defaults • Large effect on outcomes • If a default isn’t right for somebody, she will (eventually) opt out The downside of defaults • Giving some people the wrong default is inevitable when population is heterogeneous and only one default can be chosen • Sometimes it takes people a long time to opt out Open question Who is most vulnerable to getting stuck at a bad default? Default effects by income in Madrian and Shea (2001) Fraction at default contribution rate (3%) and asset allocation (100% money market) 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Income Why it’s difficult to interpret that graph • Low-income workers could persist longer at default because it is closer to their target rate, so less incentive to opt out quickly • Relative persistence could change if we chose a different default What we’d like to know Holding fixed distance between default and target, are low-income workers are more inertial? Key empirical challenge • Distribution of target rates by income group unobserved – Thus, hard to control for default’s distance to target • In particular, target rate is unobserved for those who are still at the default. Mixture of – Those for whom default = target – Those for whom default ≠ target, but they haven’t moved there Objectives • Estimate distribution of target rates by income group separately for each company • Estimate per-period probability of opting out to each target rate by income group separately for each company • Estimate each income group’s probability of remaining stuck at default 2 years after hire when it is not target rate Our empirical approach Assume target rate doesn’t change over observation period (2 years after hire) • Two time intervals after hire • – Initial period (usually 2 months): Higher opt-out activity – Later period: Lower opt-out activity • Assume monthly probability of opting out to target ci is constant across time during later period – But varies by target rate × company × income group Intuition for empirical methodology Suppose we observe 20 people opt out to 5% contribution rate in month 3 (start of later period) • Consistent with numerous possibilities • # people with 5% target who haven’t moved at beginning of month 3 Monthly probability of moving # people with 5% target who haven’t moved at beginning of month 4 100 20% 80 60 33% 40 40 50% 20 Intuition for empirical methodology Suppose we also observe 16 people opt out to 5% in month 4 • If monthly opt-out probability is constant, then we can infer which possibility is correct • • # people with 5% target who haven’t moved at beginning of month 3 Monthly probability of moving # people with 5% target who haven’t moved at beginning of month 4 40 50% 20 Above scenario implies 20 × 0.5 = 10 opt-outs in month 4 → Inconsistent with data Intuition for empirical methodology • # people with 5% target who haven’t moved at beginning of month 3 Monthly probability of moving # people with 5% target who haven’t moved at beginning of month 4 100 20% 80 Above scenario implies 80 × 0.2 = 16 opt-outs in month 4 → Consistent with data Intuition for empirical methodology • We know from last step how many people have a 5% target but haven’t opted out at beginning of month 3 • People with 5% target at beginning of initial period = Opt-outs in initial period + People with 5% target at beginning of later period • Probability of opting out to 5% during initial period = Opt-outs in initial period / People with 5% target at beginning of initial period High vs. low income definition Split employees into those above vs. below sample-wide median income ($61,228) Sample Firm Industry Hire Dates Covered Sample Size Initial Period Default Rate A Pharma/Health Jan 2002 – Dec 2005 14,961 14 months 3% B Medical Tech Jan 2002 – Oct 2003 5,452 3 months 3% C Manufacturing Oct 2008 – Dec 2010 1,931 2 months 6% D Manufacturing Jan 2002 – Dec 2006 5,193 2 months 6% E Computer Hardware Jan 2002 – Dec 2002 1,872 2 months 0% F Insurance Aug 2003 – Dec 2006 5,819 2 months 0% G Business Services Jan 2002 – Dec 2003 3,165 2 months 0% H IT Services Mar 2002 – Dec 2004 8,289 2 months 0% I Pharma/Health Jan 2002 – Dec 2004 5,453 12 months 0% J Telecom Services Jan 2002 – Dec 2003 2,169 2 months 0% Probability of being at default after 2 years when it’s not your target 18.6% 13.5% 6.6% 4.7% Automatic enrollment firms Low-income Opt-in enrollment firms High-income Adjusting for differences in target distributions • Less likely to opt out within 2 years if default is close to target rate • Differences between low- and high-income sticking probabilities partially driven by differences in target rates • In next graph, set target rate distribution equal to average of low- and high-income for both income groups Probability of being at default after 2 years when it’s not your target, holding rate preferences fixed 15.3% 12.5% 7.2% Automatic enrollment firms Low-income 6.2% Opt-in enrollment firms High-income Conclusion • Low-income individuals less likely to opt out of default • Default choices should place higher weight on low-income individuals’ needs • To be explored: Do defaults change target contribution rates?