The Protection of Fragile Ecosystems during Armed Conflict

advertisement

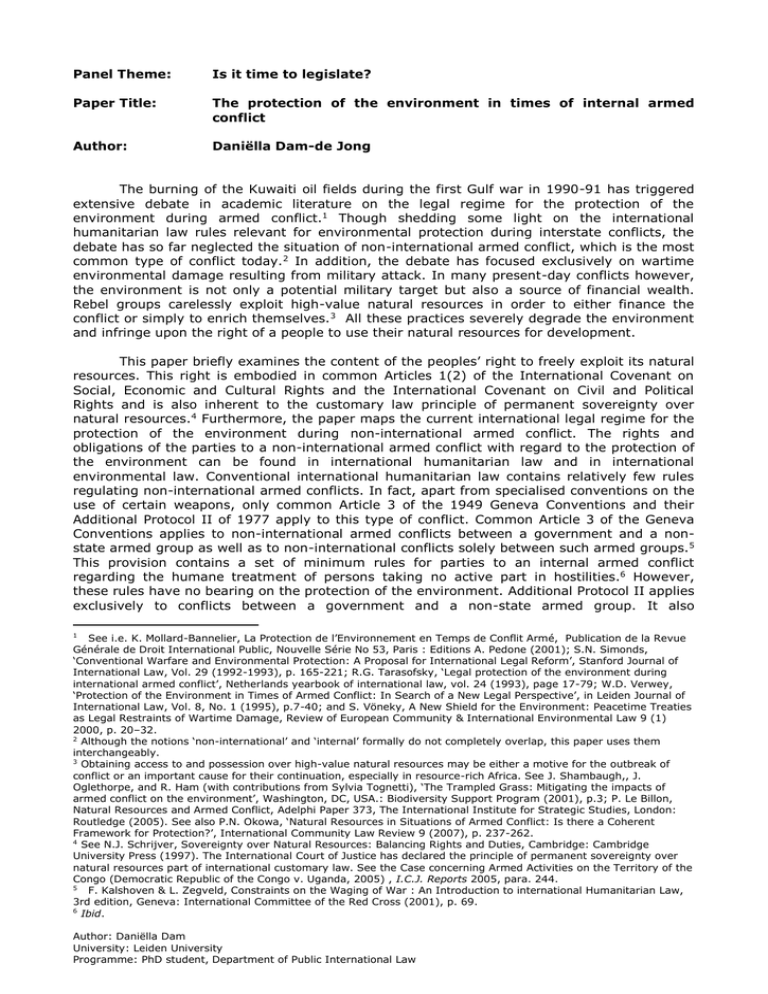

Panel Theme: Is it time to legislate? Paper Title: The protection of the environment in times of internal armed conflict Author: Daniëlla Dam-de Jong The burning of the Kuwaiti oil fields during the first Gulf war in 1990-91 has triggered extensive debate in academic literature on the legal regime for the protection of the environment during armed conflict.1 Though shedding some light on the international humanitarian law rules relevant for environmental protection during interstate conflicts, the debate has so far neglected the situation of non-international armed conflict, which is the most common type of conflict today.2 In addition, the debate has focused exclusively on wartime environmental damage resulting from military attack. In many present-day conflicts however, the environment is not only a potential military target but also a source of financial wealth. Rebel groups carelessly exploit high-value natural resources in order to either finance the conflict or simply to enrich themselves.3 All these practices severely degrade the environment and infringe upon the right of a people to use their natural resources for development. This paper briefly examines the content of the peoples’ right to freely exploit its natural resources. This right is embodied in common Articles 1(2) of the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and is also inherent to the customary law principle of permanent sovereignty over natural resources.4 Furthermore, the paper maps the current international legal regime for the protection of the environment during non-international armed conflict. The rights and obligations of the parties to a non-international armed conflict with regard to the protection of the environment can be found in international humanitarian law and in international environmental law. Conventional international humanitarian law contains relatively few rules regulating non-international armed conflicts. In fact, apart from specialised conventions on the use of certain weapons, only common Article 3 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocol II of 1977 apply to this type of conflict. Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions applies to non-international armed conflicts between a government and a nonstate armed group as well as to non-international conflicts solely between such armed groups.5 This provision contains a set of minimum rules for parties to an internal armed conflict regarding the humane treatment of persons taking no active part in hostilities.6 However, these rules have no bearing on the protection of the environment. Additional Protocol II applies exclusively to conflicts between a government and a non-state armed group. It also See i.e. K. Mollard-Bannelier, La Protection de l’Environnement en Temps de Conflit Armé, Publication de la Revue Générale de Droit International Public, Nouvelle Série No 53, Paris : Editions A. Pedone (2001); S.N. Simonds, ‘Conventional Warfare and Environmental Protection: A Proposal for International Legal Reform’, Stanford Journal of International Law, Vol. 29 (1992-1993), p. 165-221; R.G. Tarasofsky, ‘Legal protection of the environment during international armed conflict’, Netherlands yearbook of international law, vol. 24 (1993), page 17-79; W.D. Verwey, ‘Protection of the Environment in Times of Armed Conflict: In Search of a New Legal Perspective’, in Leiden Journal of International Law, Vol. 8, No. 1 (1995), p.7-40; and S. Vöneky, A New Shield for the Environment: Peacetime Treaties as Legal Restraints of Wartime Damage, Review of European Community & International Environmental Law 9 (1) 2000, p. 20–32. 2 Although the notions ‘non-international’ and ‘internal’ formally do not completely overlap, this paper uses them interchangeably. 3 Obtaining access to and possession over high-value natural resources may be either a motive for the outbreak of conflict or an important cause for their continuation, especially in resource-rich Africa. See J. Shambaugh,, J. Oglethorpe, and R. Ham (with contributions from Sylvia Tognetti), ‘The Trampled Grass: Mitigating the impacts of armed conflict on the environment’, Washington, DC, USA.: Biodiversity Support Program (2001), p.3; P. Le Billon, Natural Resources and Armed Conflict, Adelphi Paper 373, The International Institute for Strategic Studies, London: Routledge (2005). See also P.N. Okowa, ‘Natural Resources in Situations of Armed Conflict: Is there a Coherent Framework for Protection?’, International Community Law Review 9 (2007), p. 237-262. 4 See N.J. Schrijver, Sovereignty over Natural Resources: Balancing Rights and Duties, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1997). The International Court of Justice has declared the principle of permanent sovereignty over natural resources part of international customary law. See the Case concerning Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda, 2005) , I.C.J. Reports 2005, para. 244. 5 F. Kalshoven & L. Zegveld, Constraints on the Waging of War : An Introduction to international Humanitarian Law, 3rd edition, Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross (2001), p. 69. 6 Ibid. 1 Author: Daniëlla Dam University: Leiden University Programme: PhD student, Department of Public International Law establishes a threshold for armed groups with regard to their degree of organization. Despite the Protocol’s more limited field of application, Additional Protocol II enhances the protection of the civilian population in the situation of internal conflict by including provisions on the protection of specific objects. Some of these are relevant to the protection of the environment. Article 14 protects objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population and Article 15 prohibits to attack dams, dykes and nuclear electrical generating stations. Besides Articles 14 and 15, mention should be made of Article 4 (2) (g) of Additional Protocol II which prohibits pillage. It will be argued that this provision also applies to the looting and plundering of natural resources. The international humanitarian law regime with regard to the protection of the environment is further complemented by rules emanating from international environmental law, which are considered to remain applicable during non-international armed conflict.7 The government thus remains bound by its obligations under international environmental law, in so far as the circumstances do not preclude its application. Nonetheless, contrary to the applicable instruments of international humanitarian law, international environmental treaties do not contain provisions expressly binding non-state actors. In conclusion, the current legal framework for the protection of the environment and natural resources during non-international armed conflict is modest but not without merit. International humanitarian and international environmental law complement each other in offering basic protection to the environment during armed conflict. In this way, the legal framework provides a foundation for post-conflict reconstruction. The report of the Secretary-General on the protection of the environment during armed conflict for example concludes that “other legal provisions regarding the environment, for example, rules of general or bilateral international treaties, remain applicable in principle to a State in which there is an internal conflict”. See UN Doc. A/48/269 of 29 July 1993, p. 9. 7 Author: Daniëlla Dam University: Leiden University Programme: PhD student, Department of Public International Law