Bueno_2012.doc

advertisement

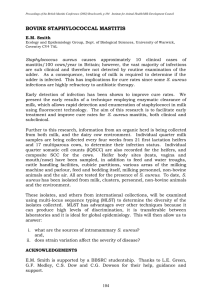

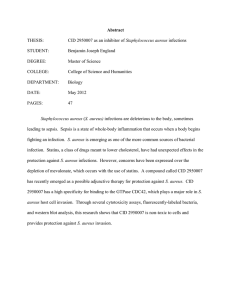

1 Title: Phage inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus in fresh and hard-type cheeses 2 3 Authors: Edita Bueno, Pilar García, Beatriz Martínez and A. Rodríguez* 4 5 Addresses: Instituto de Productos Lácteos de Asturias (IPLA-CSIC). Department of 6 Technology and Biotechnology of Dairy Products. 33300- Villaviciosa, Asturias, Spain. 7 8 9 10 * 11 Dr. Ana Rodriguez 12 IPLA-CSIC 13 33300-Villaviciosa, Asturias 14 Spain. 15 e-mail: anarguez@ipla.csic.es 16 Phone: +34 985 89 21 31 (Ext. 24) 17 Fax: +34 985 89 22 33 Corresponding author: 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 1 26 Abstract 27 Bacteriophages are regarded as natural antibacterial agents in food since they are able to 28 specifically infect and lyse food-borne pathogenic bacteria without disturbing the 29 indigenous microbiota. Two Staphylococcus aureus obligately lytic bacteriophages 30 (vB_SauS-phi-IPLA35 and vB_SauS-phi-SauS-IPLA88), previously isolated from the 31 dairy environment, were evaluated for their potential as biocontrol agents against this 32 pathogenic microorganism in both fresh and hard-type cheeses. Pasteurized milk was 33 contaminated with S. aureus Sa9 (about 106 CFU/mL) and a cocktail of the two lytic 34 phages (about 106 PFU/mL) was also added. For control purposes, cheeses were 35 manufactured without addition of phages. In both types of cheeses, the presence of 36 phages resulted in a notorious decrease of S. aureus viable counts during curdling. In 37 test fresh cheeses, a reduction of 3.83 log CFU/g of S. aureus occurred in 3 h compared 38 with control cheese, and viable counts were under the detection limits after 6 h. The 39 staphylococcal strain was undetected in both test and control cheeses at the end of the 40 curdling process (24 h) and, of note, no re-growth occurred during cold storage. In hard 41 cheeses, the presence of phages resulted in a continuous reduction of staphylococcal 42 counts. In curd, viable counts of S. aureus were reduced by 4.64 log CFU/g compared 43 with the control cheeses. At the end of ripening, 1.24 log CFU/g of the staphylococcal 44 strain was still detected in test cheeses whereas 6.73 log CFU/g was present in control 45 cheeses. Starter strains were not affected by the presence of phages in the cheese 46 making processes and cheeses maintained their expected physico-chemical properties. 47 48 Keywords 49 Lytic phage, biocontrol, cheese, Staphylococcus aureus 50 2 51 1. Introduction 52 The current consumer demand for nutritious food products, containing minimal 53 amounts of chemically synthesized additives, with acceptable shelf-life and high 54 organoleptical quality has driven research into alternative food preservation methods to 55 fight against pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms in food. Namely, biopreservation 56 aims at enhancing food safety by using natural microbiota and/or their metabolites with 57 antimicrobial properties. Bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria and 58 bacteriophages (phages) are good examples of biopreservation agents (García et al., 59 2010; Galvez et al., 2010). 60 The use of virulent phages that infect and lyse bacterial pathogen and spoilage 61 bacteria in food is quite recent and this strategy has been explored along the food chain 62 from the production of primary commodities to shelf life extension of manufactured 63 food products (García et al., 2010; Mahony et al., 2011). A remarkable advantage of the 64 application of phages as food biopreservatives is their specificity towards their hosts, 65 meaning that undesired target bacteria are infected, and consequently killed, without 66 disturbing the endogenous microbiota (i.e., starter cultures used in fermented foods). 67 Besides, no adverse effects on the human commensal microbiota have been reported 68 after oral administration of bacteriophages in rats and humans (Carlton et al., 2005; 69 Bruttin and Brüssow, 2005). 70 The potential of phages as biocontrol agents in food is supported by several 71 studies that indicate an efficient reduction of pathogen levels in meat (Atterbury et al., 72 2003; Whichard et al., 2003), fresh-cut produce (Leverentz et al., 2001, 2003), dairy 73 products (Modi et al., 2001, García et al., 2007, Guenther and Loessner, 2011) or 74 reconstituted infant formula (Kin et al., 2007). Phages were also effective in controlling 75 the growth of beer spoilage bacteria (Deasy et al., 2011). Some phage preparations are 3 76 already commercially available. This is the case of ListexTM P100 that has been 77 recognized as safe by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and has been also 78 approved by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) as an antimicrobial processing 79 aid to combat Listeria monocytogenes in foods (www.micreosfoodsafety.com). 80 Nevertheless, phages intended as biocontrol agents in food must be evaluated carefully 81 to reduce the risk of spreading virulent factors among the bacterial population (García et 82 al., 2008; Cheng and Novick, 2009). Accordingly, the use of obligately lytic instead of 83 temperate phages is encouraged because the latter are the leading cause of dissemination 84 of virulent factors (Brüssow et al., 2004). 85 The food industry is mostly concerned with food-borne pathogens such as L. 86 monocytogenes, Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, Staphylococcus aureus and 87 enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. In particular, S. aureus has been responsible for 88 outbreaks associated with milk and dairy products, particularly those strains able to 89 produce heat stable enterotoxins (de Buyser et al., 2001; Tirado and Schmidt, 2000, Le 90 Loir et al., 2003; Little et al., 2008). Of note, the largest proportion of verified outbreaks 91 caused by staphylococcal toxins (21.6 %) was attributed to cheese in a recent report 92 (EFSA and ECDC, 2011). Bovine mastitis is an important source of milk contamination 93 by S. aureus as this pathogen is one of the most prevalent agents of intramammary 94 infections in dairy ruminants (Katsuda et al., 2005). Postpasteurization contamination of 95 milk and dairy products by food handlers has also been reported (Waldvogel, 2001). 96 The European regulation has set the upper limit for coagulase positive staphylococci at 97 105 CFU/g in cheese. Above this limit, enterotoxin determination must be conducted in 98 the cheese batch (Commission Regulation [EC] Nº 2073/2005). Therefore, it is very 99 important to control S. aureus growth throughout the cheese-making process (Delbes et 100 al., 2006; Meyrand et al., 1999). 4 101 Bacteriophages vB_SauS-phi-IPLA35 (in short, phiIPLA35) and vB_SauS-phi- 102 IPLA88 (in short, phiIPLA88) belong to the Siphoviridae family and are lytic 103 derivatives of temperate phages ΦA72 and ΦH5, previously isolated from the dairy 104 environment. These bacteriophages were able to inhibit S. aureus grown in milk and 105 curd manufacturing processes (García et al., 2007; 2009). Regarding this, the aim of this 106 study was to evaluate the suitability of these lytic S. aureus phages as biocontrol agents 107 against this pathogen in both fresh and hard-type cheeses. 108 109 110 2. Materials and methods 111 112 2.1. Bacterial strains and growth conditions 113 S. aureus Sa9, isolated from a mastitic bovine milk sample, was grown in 2xYT 114 broth (Sambrook et al., 1989) at 37ºC for 18 h. Baird-Parker Agar supplemented with 115 egg yolk-tellurite (Scharlau Chemie, S.A. Barcelona, Spain) was used for differential 116 counting. The strains Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IPLA 542, L. lactis subsp. lactis 117 biovar. diacetylactis IPLA 838, and Leuconostoc citreum IPLA 979, grown in 118 commercial skimmed UHT milk, were mixed in the ratio 56: 19: 25 (%, v/v) and used 119 as starter cultures (1% v/v) in cheesemaking trials, as previously described (Cárcoba et 120 al. 2000). 121 122 2.2. Bacteriophages 123 Bacteriophages phi-IPLA35 and phi-IPLA88 were routinely propagated on S. 124 aureus Sa9 as previously described (García et al., 2007). Concentrated phage 125 preparations were obtained by ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 90 min) of culture 5 126 supernatants followed by CsCl gradient centrifugation (Sambrook et al., 1989). Double- 127 plaque assays were performed to determine the phage titer by using 100 µL of a S. 128 aureus Sa9 overnight culture and 100 µL of the appropriate phage dilution. 129 130 2.3. Bacterial-phage challenge test during cheese manufacture 131 Three independent trials of fresh and hard-type cheeses were manufactured in 132 the Pilot Plant at the Instituto de Productos Lácteos de Asturias (IPLA-CSIC) following 133 traditional manufacturing methods. For each fresh-type cheese (acid-coagulated cheese) 134 trial, pasteurized whole bovine milk (72 °C, 15 s) was cooled to 25 °C and placed into 135 two 12 L vats (control and test) and supplemented with 0.02% CaCl2. Each vat was 136 inoculated at 1% (v/v) (about 107 CFU/mL) with an overnight culture of the mixed 137 starter culture described above and contaminated with S. aureus Sa9 (about 1.7 106 138 CFU/mL). A final concentration of about 106 PFU/mL of a cocktail of phages phi- 139 IPLA35 and phi-IPLA88 (1:1) was also added to the test vat as biocontrol agent. A 140 small amount of calf rennet (0.025 g/liter; activity 1:10,000, Laboratorios Arroyo, 141 Santander, Spain) was added 2 h after the starter addition to increase the firmness of the 142 coagulum. At the end of the coagulation process (24 h), the acid curd was placed in a 143 linen-covered perforated container and kept overnight at room temperature for 144 completed draining. Drained curd was salted with dry salt (1.5% w/w) and packaged in 145 100 ml sterile containers and stored at 4ºC for up to 14 days. 146 For each hard-type cheese trial, pasteurized whole bovine milk was cooled to 147 32ºC and placed into two 12 L vats (control and test). CaCl2 supplementation and starter 148 culture addition were performed as indicated for fresh cheeses. Both cheese vats were 149 contaminated with S. aureus Sa9 (about 8 × 105 CFU/mL). The phage mixture (5 × 106 150 PFU/mL) was also added to the test vat. Calf rennet (0.3 g/L, activity 1:10,000, 6 151 Laboratorios Arroyo), was added 60 min after inoculation, and milk coagulation was 152 performed along 45 min at 32ºC. Curd was cut into cubes of ca. 5 mm and stirred into 153 the whey for 90 min. Whey was drained off, the curd filled into cylindrical molds and 154 pressed for 1.25 h at 1.5 kg/cm2. Cheese pieces (about 300 g each) were placed in 155 saturated brine for 30 min. Ripening took place at 11ºC and 80% relative humidity for 156 30 days. 157 158 2.4. Microbiological analyses 159 Samples of milk (10 ml), curd (10 g), and cheese (10 g) were aseptically taken in 160 duplicate at different times. Curd and cheese samples were homogenized in 90 ml of a 161 prewarmed sterile 2% sodium citrate solution in a Stomacher Lab-Blender (Seward 162 Medical, London, UK). Decimal dilutions of milk and homogenates were made in 163 quarter-strength Ringer solution (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) and plated in 164 triplicate in the appropriate medium. MRS agar was used for lactic acid bacteria 165 counting, and Baird-Parker Agar supplemented with egg yolk-tellurite for S. aureus 166 counting. Phage titere was obtained by plaque assays on 2xYT medium. 167 168 2.5 Physico-chemical analyses of cheeses 169 pH was measured with a MicropH 2001 pHmeter (Crison, Barcelona, Spain). 170 Dry matter, fat and protein content were determined according to the International Dairy 171 Federation (IDF, 1982, 1991, 1993). A 926 Chloride Analyser (Corning Medical and 172 Scientific, England) was used to determine the NaCl content. 173 174 2.6. Statistical analysis 7 175 Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS-PC +11.0 software (SPSS, 176 Chicago, IL, USA). Data related to gross composition (dry matter, protein, fat and 177 sodium chloride content) and S. aureus counts were subjected to ANOVA. Tests were 178 performed within each sampling time using type of cheese as a factor with two 179 categories: cheese manufactured in the presence and in the absence of phages. 180 181 3. Results and Discussion 182 183 3.1. Effect of phage cocktail on S. aureus Sa9 growth in fresh-type cheese 184 The ability of the phage cocktail to control the development of S. aureus Sa9 185 was investigated during manufacturing and cold storage of fresh cheese. Figure 1 shows 186 the evolution of the lactic acid microbiota and staphylococcal counts throughout 187 curdling and storage at 4ºC in the presence and in the absence of phages. Similar trend 188 was shown by the starter strains whose level increased about 2.5 log units during the 189 coagulation process (24 h) and decreased during the storage period in both control and 190 test cheeses (P>0.05). Moreover, pH similarly dropped from 6.6 in milk to 4.24-4.25 at 191 the end of the coagulation process in both cheese batches and a slight increase was 192 observed during storage. As expected, because of their high specificity, the presence of 193 phages did not compromise starter performance and cheese making proceeded 194 undisturbed. In fact, the physico-chemical parameters of test and control cheeses were 195 very similar showing no significant differences (P>0.05). Mean values of dry matter 196 (20.06 0.42 % [w/w]), protein content (43.91 0.32 % of dry matter), fat content 197 (45.91 1.82 % of dry matter) and NaCl (1.5 0.15 g /100 g cheese) in both cheeses 198 during cold storage were within the standards of fresh-type (acid coagulated) cheeses 199 (Schulz-Collins and Senge, 2004). 8 200 The presence of phages resulted in a quick and significant reduction of the 201 staphylococcal population compared with control cheeses (P<0.05). Viable counts 202 dropped from 6.25 log CFU/g in milk to 3.38 log units after 3 h and were under the 203 detection limits (<10 CFU/g) in 6 h (Fig. 1B). By contrast, in control cheeses, S. aureus 204 was able to multiply reaching levels of 7.20 log CFU/g at 6 h (Fig. 1A). In both cases, 205 staphylococcal counts were undetectable at 24 h. This is most likely due to the 206 restrictive environment for staphylococcal survival created by the low pH (4.24) after 207 curdling. It is worth mentioning that S. aureus re-growth was not observed in either 208 cheese batch during cold storage for 14 d. 209 The negative impact of the low pH on S. aureus survival has been previously 210 reported (Lanciotti et al., 2001; Lindqvist et al., 2002; Alomar et al., 2008). Of note, 211 lactic acid bacteria can contribute to S. aureus inhibition not only by decreasing pH but 212 also by producing bacteriocins (Rilla et al. 2004) or H2O2 (Ito et al. 2003). In any case, 213 according to our results, phages contributed considerably to accelerate S. aureus 214 inactivation lowering the risk of enterotoxin accumulation by effectively inhibiting S. 215 aureus multiplication long before pH values were low enough to be safe. 216 Remarkably, our results also showed that phage replication could take place 217 within the cheese matrix under these specific conditions. Indeed, an increase of the 218 phage titre was observed in the first 3 h and then remained stable until 6 h (Fig. 1B). 219 However, phage titre decreased thereafter probably due to partial inactivation of the 220 phages caused by low pH (García et al., 2007). 221 222 3.2. Effect of phage cocktail on S. aureus Sa9 growth in hard-type cheeses 223 The lactic acid microbiota showed a similar evolution in control and phage- 224 treated cheeses throughout manufacturing and ripening (P>0.05) (Figure 2). The mean 9 225 counts in milk (6.64 log CFU/mL) increased about 2 log units during the coagulation 226 process. This was due to the growth of the starter strains, as reflected by the decrease in 227 pH from 6.64 in milk to 6.05-5.98 in curd, and to the concentration of cells in the curd 228 after whey drainage. Further multiplication of bacteria occurred until 3-day control 229 cheeses in which the viable counts reached 9.5 log CFU/g and remained unchanged 230 until the end of ripening. Regarding the gross composition parameters, both cheeses 231 showed a similar trend. However, significant differences were observed in dry matter 232 content of 15-day old cheeses (P<0.05) and in salt content of 15-day and 30-day old 233 cheeses (P<0.05) (Table 1). 234 A very strong bactericidal effect of the lytic phages on the S. aureus Sa9 strain 235 was observed during cheese manufacturing (Fig. 2). The presence of phages resulted in 236 a fast and continuous decrease of staphylococcal viable counts dropping from the initial 237 milk contamination level (5.9 log CFU/mL) to 1.24 log CFU/g at the end of the ripening 238 period. This contamination level is low enough to avoid the production of sanitary risk 239 levels of enterotoxins (Belay & Rasooly, 2002), one of relevant virulent factors 240 associated to S. aureus and produced by about 25% of staphylococcal isolates from 241 foods (Dinges et al., 2000). Enterotoxin in soft-cheese made with milk highly 242 contaminated with S. aureus (7.5 log CFU/g) and treated with 500 MPa has even been 243 detected after 30 days of ripening in spite of a viable count reduction of 4.7 log CFU/g 244 was observed (López Pedemonte et al., 2006). Thus, a very quick reduction of the initial 245 staphylococcal contamination levels is essential to avoid enterotoxin production. 246 In the absence of phages, by contrast, an increase of 2.27 log CFU/g of 247 staphylococcal population occurred during the coagulation process as a consequence of 248 growth and cell concentration. The highest level of the strain was detected in one-day 249 old cheese (8.17 log CFU/g). A slight and continuous decline further occurred until 6.73 10 250 log CFU/g at 30 days of ripening is reached, this level being 5.5 log CFU/g higher than 251 that detected in phage-treated cheeses. 252 In parallel with S. aureus Sa9 initial decrease, a slight increase of phage titer 253 occurred that remained constant until the end of ripening. The stability of phage titer 254 was previously observed in enzymatic curds (García et al., 2007). In spite of the 255 presence of a stable phage titre throughout ripening, a complete elimination of S. aureus 256 was not achieved. This supports previous observations indicating that successful phage 257 infection and subsequent killing of the host cells are strongly dependent on the ratio 258 phages/bacteria (Cairns et al., 2009). Thus, the phage concentration to be used must be 259 specifically optimized for each food system to ensure the contact of the passively 260 diffusing phage particles with their host cells (Hagens and Offerhaus, 2008). Regarding 261 this, a minimum phage concentration (about 2 × 108 PFU/mL) has been reported for 262 inactivating S. aureus in milk (Obeso et al., 2010). Similar phage concentration has 263 required for inactivation close to 100% of Salmonella in LB broth (Bigwoog et al., 264 2009). High phage concentration (over 3 × 108 PFU/cm2) was also used to control the 265 surface contamination of soft cheeses (Camembert and Limburger-type) by Listeria 266 monocytogenes. The higher the phage dose, the higher the effectiveness of virulent 267 phage A511 on both cheeses (Guenther and Loessner, 2011). 268 Physical and chemical factors associated with the food matrix could also 269 compromise the successful use of phages as biocontrol agents (Guenther et al., 2009). It 270 has been reported that whey milk proteins inhibited phage K binding to S. aureus (Gill 271 et al., 2006). On the other hand, a reduced firmness and higher moisture of coagulum 272 facilitated phage activity against Salmonella in Cheddar cheese made with pasteurized 273 milk compared to that of raw milk (Modi et al., 2001). In our case, the quick increase of 274 the dry matter (and the concomitant moisture decrease) that we observed in hard-type 11 275 cheese (Table 1) could have hampered phages to encounter the bacterial cell host and 276 thus, it could contribute to the presence of viable staphylococcal cells at the end of 277 ripening. 278 In conclusion, phages have been shown to be effective on reducing S. aureus 279 counts in both fresh and hard-type cheeses without compromising the performance of 280 the starter culture or their physico-chemical properties. In fresh cheeses, both low pH 281 and phages contributed to clearance of the pathogen. In hard cheeses, the pathogen was 282 not totally eliminated but its numbers were kept far below the limits for toxin 283 production in the presence of phages. 284 285 Acknowledgments 286 This work was supported by grants AGL2009-13144-C02-01 (Ministry of Science and 287 Innovation, Spain), and IB08-052 and COF07-006 (Science, Technology and 288 Innovation Programme, Principado de Asturias, Spain) 289 290 References 291 Alomar, J., Lebert, A., Montel, M.C., 2008. Effect of temperature and pH on growth of 292 Staphylococcus aureus in co-culture with Lactococcus garvieae. Current 293 Microbiology, 56, 408-412. 294 Atterbury, R.J., Connerton, P.L., Dodd, C.E., Rees, C.E., I. F. Connerton, I.F., 2003. 295 Application of host-specific bacteriophages to the surface of chicken skin leads 296 to a reduction in recovery of Campylobacter jejuni. Applied and Environmental 297 Microbiology 69, 6302-6306. 12 298 Belay. N., Rasooly, A., 2002. Staphylococcus aureus growth and enterotoxin A 299 production in an anaerobic environment. Journal of Food Protection 65, 199- 300 204. 301 Bigwood, T., Hudson, J.A., Billington, C., 2009. Influence of host and bacteriophage 302 concentration on the inactivation of food-borne pathogenic bacteria by two 303 phages. FEMS Microbiology Letters 291, 59-64. 304 Brüssow, H., Canchaya, C., Hardt, W. D., 2004. Phages and the evolution of bacterial 305 pathogens: From genomic rearrangements to lysogenic 306 Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 68, 560–602. conversion. 307 Bruttin, A., Brussow, H., 2005. Human volunteers receiving Escherichia coli phage T4 308 orally: a safety test of phage therapy. Antimicrobial Agents in Chemotheraphy 309 49, 2874–2878. 310 Cairns, B.J., Timms, A.R., Jansen, V.A.A., Connerton, I.F., Payne, R.J.H., 2009. 311 Quantitative models of in vitro bacteriophage–host dynamics and their 312 application to phage therapy. PLoS Pathogens 5, 1-10. 313 Cárcoba, R., Delgado, T., Rodríguez, A., 2000. Comparative performance of a mixed 314 strain starter in cow’s milk, ewe’s milk and mixtures of these milks. European 315 Food Research and Technology 211, 141–146. 316 Carlton, R.M., Noordman, W.H., Biswas, B., de Meester, E.D. Loessner, M.J., 2005. 317 Bacteriophage P100 for control of Listeria monocytogenes in foods: Genome 318 sequence, bioinformatic analyses, oral toxicity study, and application. 319 Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 43, 301-312. 320 321 Cheng, J., Novick, R. P., 2009. Phage-mediated intergeneric tranfer of toxin genes. Science 323, 139-141. 13 322 323 Commission regulation (EC) no. 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs, European Commission, Brussels, Belgium. 324 De Buyser M L., Dufour, B., Maire, M., Lafarge, V., 2001. Implication of milk and 325 milk products in foodborne diseases in France and in different industrialised 326 countries. International Journal of Food Microbiology 67, 1-17. 327 Deasy, T., Mahony, J., Neve, H., Heller, K.J., van Sinderen, D., 2011. Isolation of a 328 virulent Lactobacillus brevis phage and its application in the control of beer 329 spoilage. 330 Delbes, C., Alomar, J., Chougui, N., Martin, J., Montel M.C., 2006. Staphylococcus 331 aureus growth and enterotoxin production during manufacture of non-cooked, 332 semi-hard cheese from cow’s raw milk. Journal of Food Protection 69, 2161- 333 2167. 334 335 Dinges, M.M., Orwin, P.M., Schlievert, P.M., 2000. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 13, 16-34. 336 European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and European Centre for Disease Prevention 337 and Control (ECDC). 2011. The European Union Summary Report on Trends 338 and Sources of Zoonoses, Zoonotic Agents and Food-borne Outbreaks in 2009. 339 EFSA Journal 9: 2090, 1-378. 340 341 Gálvez, A., Abriouel, H., Benomar, N., Lucas, R., 2010. Microbial antagonists to foodborne pathogens and biocontrol. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 21:142–148. 342 García, P., Madera, C., Martínez, B., Rodríguez, A., 2007. Biocontrol of 343 Staphylococcus aureus in curd manufacturing processes using bacteriophages. 344 International Dairy Journal 17, 1232-1239. 14 345 García, P., Madera, C., Martínez, B., Rodríguez, A., Suárez, J. E., 2009. Prevalence of 346 bacteriophages infecting Staphylococcus aureus in dairy samples and their 347 potential as biocontrol agents. Journal of Dairy Science 92, 3019-3026. 348 García, P., Martínez, B., Obeso, J., Rodríguez, A., 2008. Bacteriophages and their 349 applications in food safety. Letters in Applied Microbiology 47, 479-485. 350 García, P., Rodríguez, L., Rodríguez, A., Martínez, B., 2010. Food biopreservation: 351 promising strategies using bacteriocins, bacteriophages and endolysins. Trends 352 in Food Science and Technology 21, 373-382. 353 Gill, J.J., Sabour, P.M., Leslie, K.E., Griffiths M.W., 2006. Bovine whey proteins 354 inhibit the interaction of Staphylococcus aureus and bacteriophage K. Journal of 355 Applied. Microbiology 101, 377-386. 356 Guenther, S., Huwyler, D., Richard, S., Loessner, M.J., 2009. Virulent bacteriophage 357 for efficient biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods. Applied 358 and Environmental Microbiology 75, 93-100. 359 Guenther, S., Loessner M.J., 2011. Bacteriophage biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes 360 on soft ripened white mold and red-smear cheeses. Bacteriophage 1, 94-10. 361 Hagens, S., Offerhaus, M.L., 2008. Bacteriophages - new weapons for food safety. Food 362 Technology 62, 46-54. 363 IDF Standard 152, 1991. Milk and milk products. Determination of fat content. General 364 guidance on the use of butyrometric methods. International Dairy Federation, 365 Brussels, Belgium. 366 367 368 369 IDF Standard 20B, 1993. Milk. Determination of nitrogen content. Part 1: Kjeldahl method. International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium. IDF Standard 4A, 1982. Cheese and processed cheese. Determination of the total solids content (reference method). International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium. 15 370 Ito, A., Sato Y., Kudo S., Sato S., Nakajima H., Toba, T., 2003. The screening of 371 hydrogen peroxide-producing lactic acid bacteria and their application to 372 inactivating psychrotrophic food-borne pathogens. Current Microbiology 47, 373 231-236. 374 Katsuda, K., Hata, E., Kobayashi, H, Kohmoto, M., Kawashima, K., Tsunemitsu, H., 375 Eguchi, M., 2005. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from 376 bovine mastitic milk on the basis of toxin genes and coagulase gene 377 polymorphisms. 105, 301-305. 378 Kim, K.P., Klumpp, J., Loessner, M.J., 2007. Enterobacter sakazakii bacteriophages 379 can prevent bacterial growth in reconstituted infant formula. International 380 Journal of Food Microbiology 115, 195-203. 381 Lanciotti R., Sinigaglia M., Gardini F., Vannini L., Guerzoni M.E., 2001. Growth/no 382 growth interfaces of Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella 383 enteritidis in model systems based on water activity, pH, temperature and 384 ethanol concentration. Food Microbiology 18, 659-668. 385 386 Le Loir, Y., Baron, F., Gautier, M., 2003. Staphylococcus aureus and food poisoning. Genetics and Molecular Research 2, 63-76. 387 Leverentz, B., Conway, W.S., Alavidze, Z., Janisiewicz, W.J., Fuchs, Y., Camp, M.J., 388 Chighladze, E., Sulakvelidze, A., 2001. Examination of bacteriophage as a 389 biocontrol method for Salmonella on fresh-cut fruit: a model study. Journal of 390 Food Protection 64, 1116-1121. 391 Leverentz, B., Conway, W.S., Camp, M.J., Janisiewicz, W.J., Abuladze, T., Yang. M., 392 Saftner, R., Sulakvelidze, A., 2003. Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes on 393 fresh-cut produce by treatment with lytic bacteriophages and a bacteriocin. 394 Applied and Environmental Microbiology 69, 4519-4526. 16 395 Lindqvist R., Sylven S., Vagsholm I., 2002. Quantitative microbial risk assessment 396 exemplified by Staphylococcus aureus in unripened cheese made from raw milk. 397 International Journal of Food Microbiology 78,155-170. 398 Little, C.L., Rhoades, J.R., Sagoo, S.K., Harris, J., Greenwood, M., Mithani, V., Grant 399 K., McLauchlin, J., 2008. Microbiological quality of retail cheeses made from 400 raw, thermized or pasteurized milk in the UK. Food Microbiology 25, 304-312. 401 López-Pedemonte, T., Brinez, W.J., Roig-Sagues, A.X., Guamis, B., 2006. Fate of 402 Staphylococcus aureus in cheese treated by ultrahigh pressure homogenization 403 and high hydrostatic pressure. Journal of Dairy Science 89, 4536-4544. 404 Mahony, J., McAuliffe, O., Ross R.P., van Sinderen, D., 2011. Bacteriophages as 405 biocontrol agents of food pathogens. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 22, 157- 406 163. 407 Meyrand, A., Rozand, C.V., Gonthier, A., Mazuy, C., Gueniot, S.R., Jaubert, G., Perrin, 408 Lapeyre, C., Richard, Y., 1999. Main differences in behavior and enterotoxin 409 production of Staphylococcus aureus in two different raw milk cheeses. Revue 410 de Medécine Vétérinaire 150, 271-278. 411 Modi, R., Hirvi, Y., Hill, A., Griffiths, M.W., 2001. Effect of phage on survival of 412 Salmonella enteritidis during manufacture and storage of Cheddar cheese made 413 from raw and pasteurized milk. Journal of Food Protection, 64, 927-933. 414 Obeso, J.M., García, P., Martínez, B., Arroyo-López, F.N., Garrido-Fernández, A., 415 Rodríguez, A., 2010. Use of logistic regression for predicting Staphylococcus 416 aureus fate in pasteurized milk in the presence of two lytic phages. Applied and 417 Environmental Microbiology 76, 6038-6046. 418 Rilla, N., Martínez, B., Rodríguez, A., 2004. Inhibition of a methicillin-resistant 419 Staphylococcus aureus strain in Afuega´l Pitu cheese by the nisin Z producing 17 420 strain Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IPLA 729. Journal of Food Protection 67, 421 928-933. 422 Sambrook, J., Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E.F., 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 423 second edition, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New 424 York. 425 Schulz-Collins, D., Senge, B., 2004. Acid and acid/rennet-curd cheeses. Part A: Quark, 426 cream cheese and related varieties. In: Fox, P.F., McSweeney, P.H., Cogan, 427 T.M., Guinee, T. (Eds.), Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology. Major 428 Cheese Groups, vol. 2, third edition, Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, 429 California, 301-328. 430 Tirado, C., and Schmidt, K., 2000. WHO Surveillance Programme for Control of 431 Foodborne Infections and Intoxications in Europe. 432 (http://www.bfr.bund.de/internet/7threport/7threp_fr.htm). Seventh Report 433 Waldvogel, F.A., 2001. Staphylococcus aureus (including Staphylococcal toxic shock), 434 In: Mandell, J.L., Bennet, J.E., Dolin, R. (Eds.), Principles and practice of 435 infectious diseases. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, pp. 2069-2092. 436 Whichard, J.M., Sriranganathan, N., Pierson, F.W., 2003. Suppression of Salmonella 437 growth by wild-type and large-plaque variants of bacteriophages Felix O1 in 438 liquid culture and on chicken frankfurters. Journal of Food Protection 66, 220- 439 225. 440 18 441 Table 1 442 One-way ANOVA of different gross composition parameters performed within each 443 ripening time to compare control and test (phages added) hard-type cheeses Cheese Dry mattera Proteinb Fatb NaClc 5 Control Test 61.041.85 61.080.97 37.380.43 37.240.57 53.600.91 52.391.36 1.710.20 1.690.04 8 Control Test 63.272.77 61.241.07 38.311.59 38.181.81 51.430.97 53.370.44 3.080.17 3.100.18 15 Control Test 68.720.93 63.891.60* 37.041.53 39.134.93 51.430.97 53.632.16 3.710.14 3.270.22* 30 Control Test 69.204.55 70.244.97 36.982.25 39.624.94 52.631.64 54.166.25 3.940.04 3.590.20* Ripening time (days) 444 445 446 447 448 449 Data reported are means standard deviations of three independent trials a Dry matter (%, w/w) b Data expressed as percentage of dry matter c Salt content expressed as g NaCl/ 100 g cheese *P<0.05 19 450 Figures captions 451 452 Fig. 1. Effect of phage cocktail (phi-IPLA35 and phi-IPLA88) on growth of S. aureus 453 Sa9 in fresh-type cheese throughout manufacturing and cold storage. (A) Control cheese 454 (no phage cocktail added) (B) Test cheese (phage cocktail added). Symbols: (♦ lactic 455 acid microbiota, starter culture); (■ S. aureus Sa9); (∆ pH); (× phages). Data reported 456 are means ± standard deviations of three independent trials. One-way ANOVA was 457 performed within each sampling time to compare S. aureus Sa9 counts in control and 458 test cheeses. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. 459 460 Fig. 2. Effect of phage cocktail (phi-IPLA35 and phi-IPLA88) on growth of S. aureus 461 Sa9 in hard-type cheese throughout ripening. (A) Control cheese (no phage cocktail 462 added) (B) Test cheese (phage cocktail added). Symbols: (♦ lactic acid microbiota, 463 starter culture); (■ S. aureus Sa9); (∆ pH); (× phages). Data reported are means ± 464 standard deviations of three independent trials. One-way ANOVA was performed 465 within each sampling time to compare S. aureus Sa9 counts in control and test cheeses. 466 *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. 467 20 Bacterial counts (log CFU/g) 10 4 8 8 7 6 6 5 4 2 3 0 2 Bacterial counts (log CFU/g Phage titre (log PFU/g) 468 Fig. 1 469 470 21 10 4 8 8 7 6 6 5 4 2 3 0 2 Bacterial counts (log CFU/g) 9 7 5 3 1 7 6 5 4 3 Bacterial counts (log CFU/g) Phage titre (log PFU/g) 471 Fig. 2 8 2 472 22 9 8 7 5 3 1 7 6 5 4 3 2