Poster 58.pptx (566.8Kb)

advertisement

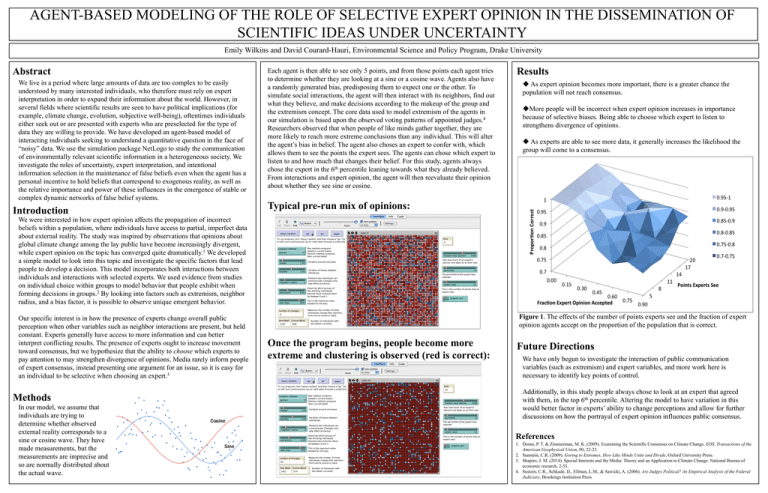

AGENT-BASED MODELING OF THE ROLE OF SELECTIVE EXPERT OPINION IN THE DISSEMINATION OF SCIENTIFIC IDEAS UNDER UNCERTAINTY Emily Wilkins and David Courard-Hauri, Environmental Science and Policy Program, Drake University Abstract We live in a period where large amounts of data are too complex to be easily understood by many interested individuals, who therefore must rely on expert interpretation in order to expand their information about the world. However, in several fields where scientific results are seen to have political implications (for example, climate change, evolution, subjective well-being), oftentimes individuals either seek out or are presented with experts who are preselected for the type of data they are willing to provide. We have developed an agent-based model of interacting individuals seeking to understand a quantitative question in the face of “noisy” data. We use the simulation package NetLogo to study the communication of environmentally relevant scientific information in a heterogeneous society. We investigate the roles of uncertainty, expert interpretation, and intentional information selection in the maintenance of false beliefs even when the agent has a personal incentive to hold beliefs that correspond to exogenous reality, as well as the relative importance and power of these influences in the emergence of stable or complex dynamic networks of false belief systems. Introduction Each agent is then able to see only 5 points, and from those points each agent tries to determine whether they are looking at a sine or a cosine wave. Agents also have a randomly generated bias, predisposing them to expect one or the other. To simulate social interactions, the agent will then interact with its neighbors, find out what they believe, and make decisions according to the makeup of the group and the extremism concept. The core data used to model extremism of the agents in our simulation is based upon the observed voting patterns of appointed judges.4 Researchers observed that when people of like minds gather together, they are more likely to reach more extreme conclusions than any individual. This will alter the agent’s bias in belief. The agent also choses an expert to confer with, which allows them to see the points the expert sees. The agents can chose which expert to listen to and how much that changes their belief. For this study, agents always chose the expert in the 6th percentile leaning towards what they already believed. From interactions and expert opinion, the agent will then reevaluate their opinion about whether they see sine or cosine. Results As expert opinion becomes more important, there is a greater chance the population will not reach consensus. More people will be incorrect when expert opinion increases in importance because of selective biases. Being able to choose which expert to listen to strengthens divergence of opinions. As experts are able to see more data, it generally increases the likelihood the group will come to a consensus. Typical pre-run mix of opinions: We were interested in how expert opinion affects the propagation of incorrect beliefs within a population, where individuals have access to partial, imperfect data about external reality. The study was inspired by observations that opinions about global climate change among the lay public have become increasingly divergent, while expert opinion on the topic has converged quite dramatically.1 We developed a simple model to look into this topic and investigate the specific factors that lead people to develop a decision. This model incorporates both interactions between individuals and interactions with selected experts. We used evidence from studies on individual choice within groups to model behavior that people exhibit when forming decisions in groups.2 By looking into factors such as extremism, neighbor radius, and a bias factor, it is possible to observe unique emergent behavior. Our specific interest is in how the presence of experts change overall public perception when other variables such as neighbor interactions are present, but held constant. Experts generally have access to more information and can better interpret conflicting results. The presence of experts ought to increase movement toward consensus, but we hypothesize that the ability to choose which experts to pay attention to may strengthen divergence of opinions. Media rarely inform people of expert consensus, instead presenting one argument for an issue, so it is easy for an individual to be selective when choosing an expert.3 Methods In our model, we assume that individuals are trying to determine whether observed external reality corresponds to a sine or cosine wave. They have made measurements, but the measurements are imprecise and so are normally distributed about the actual wave. Figure 1. The effects of the number of points experts see and the fraction of expert opinion agents accept on the proportion of the population that is correct. Once the program begins, people become more extreme and clustering is observed (red is correct): Future Directions We have only begun to investigate the interaction of public communication variables (such as extremism) and expert variables, and more work here is necessary to identify key points of control. Additionally, in this study people always chose to look at an expert that agreed with them, in the top 6th percentile. Altering the model to have variation in this would better factor in experts’ ability to change perceptions and allow for further discussions on how the portrayal of expert opinion influences public consensus. References 1. Doran, P. T. & Zimmerman, M. K. (2009). Examining the Scientific Consensus on Climate Change. EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union, 90, 22-23. 2. Sunstein, C.R. (2009). Goring to Extremes, How Like Minds Unite and Divide, Oxford University Press. 3. Shapiro, J. M. (2014). Special Interests and the Media: Theory and an Application to Climate Change. National Bureau of economic research, 2-33. 4. Sustein, C.R., Schkade, D., Ellman, L.M., & Sawicki, A. (2006). Are Judges Political? An Empirical Analysis of the Federal Judiciary, Brookings Institution Press