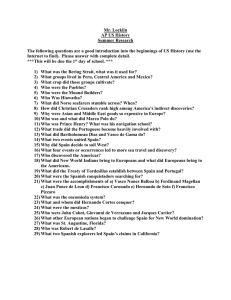

Resource Sheet 3

advertisement

Resource sheet 3 – Interpretations That not all Christians pursued the ideal of reconquest to the same degree at all times, that most had mixed motives, that the mixture differed in different individuals, that political power was envisaged as a complex of military, economic, religious, demographic and other factors, and that reconquest was sought by other means as well as by warfare are all factors inherent in any political process and should arouse no more surprise when found among the militants of the Reconquest than among those committed to any other mass movement. What is exceptional about this movement is its longevity – the fact that a single political objective could survive for over seven centuries, constantly attracting the loyalty of new generations of adherents until it was finally achieved. (p.3-4) Only Spain was able to conquer, administer, Christianise and Europeanise the populous areas of the New World precisely because during the previous seven centuries her society had been constructed for the purpose of conquering, administering, Christianising and Europeanising the inhabitants of Al-Andalus. Thus if the reconquest is important in Old World history because it is the primary example of the reversal of an Islamic conquest and because it fostered the transfer of Greek and Asian culture to western Europe, in the general sweep of world history it is vital because it prepared the rapid conquest and Europeanisation of Latin America and thereby spared it most of the religious and imperialist wars which would henceforth afflict almost all the rest of mankind. (p.178) Extracts from Lomax, D.W (1978) The Reconquest of Spain Version 1 Spain 1469-1556 1 © OCR 2016 The successive generations who manned the frontier were not prompted to action by an overpowering sense of manifest religious destiny. True, the cult of St James at Compostela gave focus to religion and crusading aspirations, but the religious life of the peninsula was unlike that of any other area in Europe. Arians for a long time under the Visigoths, the later Catholics of Spain were in perpetual and intense contact with the Muslim and Jewish religions. Moreover the Spaniards were aware that they were not waging war against barbarians and the Iberian frontier was at times an area of fruitful cultural contacts. Indeed the coexistence of Christians, Muslims and Jews and the evidence of a ‘creative struggle’ indicate that, despite the drive of the reconquest or the later medieval persecution of Jews, the degree of acculturation was considerable. Christianity expanded at the expense of Islam, but it was the civilisation of Islam, in many ways richer and more cultivated, which influenced Spain and western Europe in turn. The interplay of all these influences between Christian, Muslim and Jewish cultures was of course an extremely complex process…. The later medieval period in Spanish history has traditionally posed something of a conundrum to scholars. This is partly due to the break in continuity of the reconquest and the impulse of the advancing frontier. Between the 13th century and the fall of Granada in 1492, the Iberian peninsula was plagued by a seemingly dismal succession of civil wars, meaningless bouts of anarchy and nerveless rulers. As a result, historians have tended to turn away with relief from the later medieval ‘decline’ and acclaim the advent of the Catholic kings (Ferdinand and Isabella), the creation of the modern state, the restoration of the forces of law and order at the expense of overmighty ‘feudal’ nobles, and the stern morality of a ‘new’ monarchy able to prepare the institutions for an Empire that would dominate the 16th century world. (p.4-5) Adapted from Mackay, A (1977) Spain in the Middle Ages: From Frontier to Empire 1000-1500 Version 1 Spain 1469-1556 2 © OCR 2016