Game: The Hairy Truth

advertisement

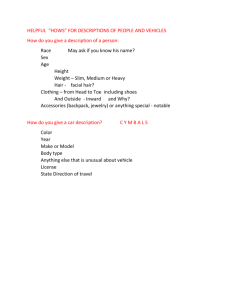

The Hairy Truth? a game to explore the co-construction of meaning via classificationist and classifier In Sorting Things Out, Bowker and Star describe the role of classifications, or systems for grouping and sorting information, in supporting human activities. Classifications are one type of social infrastructure, providing a means for decisions regarding the form and content of information exchange to be enacted in ongoing processes. For example, agreement in how to describe various industries, as standardized via the North American Industrial Classification (NAICS), enables reliable tracking of economic indicators across industrial sectors and geographic regions. With such data, one can compare performance across fields and localities, predict areas of growth, pinpoint areas of concern, and so on. Although we tend to imagine that classifications are discovered, not created, and that they accordingly represent some unified vision, the great majority of classifications used in practical work are the product of negotiation and compromise, with potentially deep disagreements suspended within their outwardly pristine structure. Further, although we tend to imagine that an appropriate category can be unambiguously identified for each item to be classified, these decisions, too, are often not easy to make, and a number of competing interests may be at play, from the workload of the classifier and the complexity of the classification to unanticipated cases, changes in the classificatory environment over time, new uses for the collected information, and the varying exigencies of each individual situation. As the practices of classifying cases evolve, we might say that the classification itself changes meaning, performing its role in a manner different from originally envisioned. All of these issues are magnified when considering classifications that systematize the collection of data about people. Information that we hope to collect, describe, and group with the best intentions may be regarded differently by those being reported on; as well, data may end up being grouped differently than we intend, or data collected for one purpose may be used for another, and so on. Your mission In this activity, you will create, in a small group, a set of categories to describe human hair color. You will then use another group’s categories to classify a set of examples. Your group will then get to see if your classification was used as you expected or not. Step 1: Create a set of categories to collect data about human hair color in the United States. Do blondes really have more fun, or just more in general? Anecdotal evidence suggests that blondes may enjoy social and economic advantages over others. To see the extent to which this may be true, either regionally or nationally, the U.S. Census will now collect data on hair color as well as other demographic information. Hair color can then be examined, alone and in combination with other demographic factors, to see if either systematic favoritism or discrimination can be discerned. In a group of 4-5 people, you will need to determine the categories employed on the census forms. In designing your classification, you should consider the following questions: How many categories should there be? How should the categories be labeled? What instructions, if any, should be given in applying the categories? Many factors may contribute to your decisions here. For example, how well does your design cover the universe of possibilities without becoming unmanageably complicated? More INF 384C Fall 2010 categories may enable more sophisticated data analysis but may also make the form more confusing, resulting in inaccurate reporting. You might also consider potential subsequent uses of this classification for additional data collection. For example, there is some interest in the medical community to learn more about potential links between hair color as a risk factor for heart disease. (Specifically, platinum blondes may have a predisposition toward high blood pressure and cholesterol. But so-called “dirty blondes” seem not to have such tendencies. More research is necessary to clarify the matter.) Record your set of categories, along with any instructions for their use, on the next page. Don’t record any conflicts, compromises, or uncertainties that may have accompanied your classification design, but do keep these in mind for class discussion later. INF 384C Fall 2010 Classification for Human Hair Color INF 384C Fall 2010 Step 2: Use another group’s classification to describe a set of examples. First, each group will give their classification to another group to use in this part of the activity. The instructor will show a series of example cases as slides. Using the other group’s classification system, you will decide, as a group, on the best category for each example. As with step 1, don’t record any conflicts, compromises, or uncertainties that may have accompanied your decision, but keep these in mind for class discussion later. Example #1 Example #2 Example #3 Example #4 Example #5 Example #6 Example #7 Example #8 Example #9 Example #10 INF 384C Fall 2010 Step 3: Return your classified examples to the originating group, and see how your own classification was used. Were the results as you expected? INF 384C Fall 2010