Syntactical Changes

advertisement

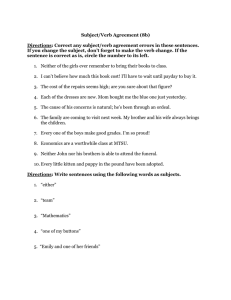

Syntactical Changes in English Dr. Muhammad Shahbaz The nature of language change Language change is inevitable, universal, continuous and, to a considerable degree, regular a n d s y s t e m a t i c . Syntactic change Rule loss In Old English, there was a morphosyntactic rule of adjective agreement, according to which, the endings of adjectives must agree with the head noun in case, number, and gender. But this syntactic rule has been lost in m o d e r n E n g l i s h . Rule addition The particle movement rule is a syntactic rule added to Modern English. This rule allows the particle in some phrasal verbs to be shifted to the right of the object. This particle movement is impossible in Old English. For example: A: He switched off the light. B: He switched the light off. Rule change Major rule changes in the structure of English sentences took place in their word orders. In Middle English, “not” was added to the end of an affirmative sentence to make it negative. But in Modern English, the negation is often made with “not” inserted between the auxiliary verb and the main verb. F o r e x a m p l e : I deny it not. I do not deny it. Old English had an elaborate case-marking system. The grammatical functions were well revealed with case markers. This system made the word order of Old English more variable than that of Modern English. For example, the word orders in Old English included SVO,VSO, SOV and OSV, but Modern English has lost the majority of case markers, therefore a basic word order of SVO has to be followed. Morpho-Syntactic Changes Question formation Negative sentence formation Case endings Verbs Other examples Morpho-Syntactic Changes B. Morpho- syntactic changes (Nash 108-11; Yule 221) 1. Q formation (Nash 108) 2. negative sentence formation (Nash 109) 3. case endings (Nash 109-110) Nouns (marked with suffixes) who/ whom questions: (Nash 108) e.g. I don’t know who/whom to give it to. (“whom”: mainly in formal speech and writing) A remnant still in the process of changing Other remnants: other pronoun forms (e.g., I/me, he/ him, she/her), plural forms. Morpho-Syntactic Changes 4. verbs: examples: (from Elgin 211) ic cepe ðu cepest he heo cepeð hit we cepað ge cepað hi cepað “I keep” “you keep” he she keeps it “we keep” “you keep” “they keep” Morpho-Syntactic Changes Old English vs Modern English Here men vndurstonden ofte by this nyght the night of synne here men understood often by this night the night of sin Morpho-Syntactic Changes Modern English: auxiliary verb raises to Tense main verb stays in VP result: main verb follows adverbs: John often went skiing. French: auxiliary verb raises to Tense main verb raises to Tense result: verb (aux or main) precedes adverbs: John went often skiing Morpho-Syntactic Changes 5. Other examples: Old English about 7th century to 11th century (1066) 1. 8 forms of “the” (Nash 110): 2. example (Framkin and Rodman) “The Man Slew the King” (6 possible word order in Old Eng.) a. se man sloh ðone cyning. b. ðone cyning sloh se man. c. se man ðone cyning sloh. d. ðone cyning se man sloh. e. sloh se man ðone cyning. f. sloh ðone cyning se man. Comparisons: The man slew the king. The king slew the man. Therefore, word order matters se: definite article only with subject ðone: definite article only with object. So, with the article (& suffixes), word order wasn’t so important— but now word order (and preposition, too) is crucial in modern English. Morpho-Syntactic Changes This change (reduction of Eng. inflections) related to Great Vowel Shift (phonological change)—which made it hard to distinguish the endings—necessitated other changes in order for the lang. to remain clear & processible, also quick & easy, & expressive (which could also be related to processes of child lang. acquisition) so, suffixes dropped out, Eng. word order becomes stricter and prepositions become more important.