محاضرة رقم 4

advertisement

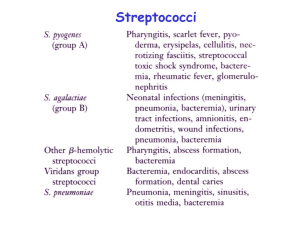

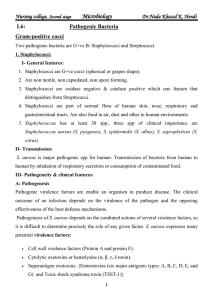

streptococaceae Assist.prof: Heavin Hannan Morphology and Identification Gram-positive cocci arranged in chains or pairs Most group A, B, and C strains produce capsules. Most strains grow as discoid colonies, 1-2 mm in diameter. Catalase-negative Grow better in media enriched with blood or tissue fluid. Most are facultative anaerobic and some are capnophilic. For most species growth and hemolysis are aided by incubation in 10% CO2. Classification Hemolysis a-hemolysis: incomplete lysis of RBC with the formation of green pigment. b-hemolysis: complete hemolysis No hemolysis Lancefield classification: a serologic classification (A to V) Biochemical reactions are used for species that can not be classified into the Lancefield classification (nongroupable), e.g. viridans streptococci. • The most important group able streptococci are A, B and D. • Among the group able streptococci, infectious disease (particularly pharyngitis) is caused by group A. • Streptococcus pneumoniae (a major cause of human pneumonia) and Streptococcus mutans and other so-called viridans streptococci (among the causes of dental caries) do not possess group antigens. Serology: Lanciefield Classification Streptococci Lanciefield classification Group A S. pyogenes Group B S. agalactiae Group C S. equisimitis Group D Enterococcus Other groups (E-U) • Streptococci classified into many groups from A-K & H-V • One or more species per group • Classification based on C- carbohydrate antigen of cell wall – Groupable streptococci • A, B and D (more frequent) • C, G and F (Less frequent) – Non-groupable streptococci • S. pneumoniae (pneumonia) • viridans streptococci – e.g. S. mutans – Causing dental carries Three types of hemolysis reaction are seen after growth of streptococci on sheep blood agar: 1. (alpha) - 2. (beta) - refers to partial hemolysis with a green coloration (from production of an unidentified product of hemoglobin) seen around the colonies complete clearing 3. (gamma) - no lysis Group A streptococcus (S. pyogenes) Streptococcus pyogenes Streptococcus pyogenes Epidemiology S. pyogenes can transiently colonize the oropharynx and skin. Diseases are caused by recently acquired strains that can establish an infection of the pharynx or skin. S. pyogenes causes pharyngitis mainly in children of 5 to 15 years old. The pathogen is spread mainly by respiratory droplets. Crowding increases the opportunity for the pathogen to spread, particularly during the winter months. Soft tissue infections are preceded by skin colonization and the organisms are introduced into the superficial or deep tissue through a break in the skin. Streptococcus pyogenes Clinical Diseases 1. Local infection with S. pyogenes Streptococcal sore throat (pharyngitis), and scarlet fever. Streptococcal pyoderma (impetigo, local infection of superficial layers of skin). Strains that cause skin infections are different from those that cause pharyngitis. Post streptococcal diseases (occurs 1-4 weeks after acute S. pyogenes infection, hypersensitivity responses) Rheumatic fever: most commonly preceded by infection of the respiratory tract. Inflammation of heart (pancarditis), joints, blood vessels, and subcutaneous tissue. Results from cross reactivity of anti-M protein Ab and the human heart tissue. Acute glomerulonephritis: preceded by infection of the skin (more commonly) or the respiratory tract. Symptoms: edema, hypertension, hematuria, and proteinuria. Initiated by Ag-Ab complexes on the glomerular basement membrane. * Rheumatic fever can be reactivated by recurrent streptococcal infections, whereas nephritis does not. Major pathogenesis factors • lipoteichoic acid/F protein – fimbriae – binds to epithelial cells • M protein – anti-phagocytic 12 S. agalactiae (group B, b-hemolytic, contains type-specific capsular polysaccharides which is the most important virulence factor and can induce protective antibodies; may colonize at lower gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary tract) Neonatal sepsis or meningitis Early-onset (during the first week of life): infection acquired in utero or at birth. Pneumonia is common in addition to meningitis. Late-onset (older infants): infection acquired from an exogenous source. (Premature infants are at greater risk.) Infection of pregnant women Urinary tract infections, endometritis, and wound infections Infection in men and non pregnant women Patients are generally older and have underlying conditions. Bacteremia, pneumonia, bone and joint infections, skin and soft tissue infections. Mortality is higher. Viridans streptococci (a-hemolytic or nonhemolytic, most are nongroupable; they, except for S. suis, are divided into 5 subgroups based on the specific diseases they cause) These streptococci colonize the oropharynx, GI tract, and GU tract; rarely on the skin surface. Diseases: Subacute endocarditis (group: Mitis) Intra-abdominal infections (group: Anginosus) Dental caries (group: Mutans) Cariogenicity of S. mutans is related to its ability to synthesize glucan from fermentable carbohydrates (e.g. sucrose) as well as to modify glucan in promoting increased adhesiveness. S. pneumoniae Laboratory Diagnosis Smears: useful for soft tissue infections or pyoderma, but not for respiratory infections. Antigen detection tests: commercial kits for rapid detection of group A streptococcal antigen from throat swabs. Detection of group A streptococci by molecular methods: PCR assay for pharyngeal specimens. Culture: Specimens are cultured on blood agar plates in air. Antibiotics may be added to inhibit growth of contaminating bacteria. Identification: serological and biochemical tests. Antibody detection ASO titration for respiratory infections. Anti-DNase B and antihyaluronidase titration for skin infections. Antistreptokinase; anti-M type-specific antibodies. Identification of Gram-positive cocci None Treatment All S. pyogenes are sensitive to penicillin G. Effective doses of penicillin or erythromycin for 10 days can prevent post streptococcal diseases. Group B streptococci are also susceptible to penicillin G. Antibiotic sensitivity test is helpful for treatment of bacterial endocarditis. S. pneumoniae Morphology and Physiology Gram-positive lancet-shaped diplococci for typical organisms. a-hemolytic. Form small round colonies on the plate, at first dome-shaped and later developing a central plateau with an elevated rim. Autolysis is enhanced in bile salt. Growth is enhanced by 5-10% CO2. Capsular polysaccharide: type-specific, 90 types. Smooth (capsular polysaccharideproducing) . rough colonies *Quellung reaction (for rapid identification of the bacteria) S. pneumoniae Pathogenesis and Immunity Pneumococci produce disease through their ability to multiply in the tissues (invasiveness). Virulence factors: capsule, cell wall polysaccharide, phosphocholine, pneumolysin, IgA protease, etc. 40-70% of humans are at sometimes carrier of virulent pneumococci. Normal respiratory tract has natural resistance to the pneumococcus. Major host defense mechanisms: ciliated cells of respiratory tract and spleen. Loss of natural resistance may be due to: 1. Abnormalities of the respiratory tract (e.g. viral RT infections). 2. Alcohol or drug intoxication; abnormal circulatory dynamics. 3. Patients undergone renal transplant; chronic renal diseases. 4. Malnutrition, general debility, sickle cell anemia, hypersplenism or splenectomy. 5. Young children and the elderly. S. pneumoniae Clinical diseases Pneumococcal pneumonia develops when the bacteria multiply rapidly in the alveolar space after aspiration. The affected area is generally localized in the lower lobes of the lungs (lobar pneumonia). Children and the elderly can have a more generalized bronchopneumonia. Resolution occurs when specific anticapsular antibodies develop. Sudden onset with fever, chills and sharp chest pain. Bloody, rusty sputum. is a rare but significant complication. Complications caused by spreading of pneumococci to other organs: sinusitis, middle ear infection, meningitis, endocarditis, septic arthritis. S. pneumoniae Laboratory diagnosis Examination of sputum Stained smears of sputum: a rapid diagnosis. Quellung test with multivalent anticapsular antibodies. Culture Specimen: sputum, aspirates from sinus or middle ear, CSF. cultured on blood agar plate in 5-10% CO2. Identification: bile solubility, optochin sensitivity, etc. for differentiation from other a-hemolytic streptococci. Additional biochemical, serologic or molecular diagnostic tests for a definitive identification. Antigen detection: detect pneumococcal C polysaccharide (teichoic acid; type-specific) in urine (bacteremic) or CSF (meningitis). Enterococci (E. faecalis, E. faecium) Physiological properties are similar to the streptococci. Form large colonies on blood plate; most are nonhemolytic. Microscopic morphology is similar to S. pneumoniae. Resistant to 6.5% NaCl, 0.1% methyl blue and grow in bile-esculin agar. More resistant to antibiotics than the streptococci. Colonize the large intestine of humans and animals. An opportunist. Clinical Diseases Enterococci One of the leading causes of nosocomial infections. Urinary tract (UTI), peritoneum (peritonitis) and heart tissue (endocarditis- a severe complication) are involved most often. Particularly common in patients with intravascular or urinary catheters, and in hospitalized patients with prolonged broadspectrum antibiotic treatment. Intra-abdominal abscess and wound infections: generally polymicrobial. Many strains are completely resistant to all conventional antibiotics. Vancomycin-resistant strains have been isolated (first reported in England and France in 1987). Laboratory Diagnosis Enterococci can be differentiated by simple biochemical tests (e.g., resistant to optochin and bile, hydrolyze PYR, etc.) Enterococci Treatment, Prevention, and Control Resistance in enterococci to aminoglycosides and vancomycin is mediated by plasmids and can be transferred to other bacteria. Combined antibiotic therapy: an aminoglycoside and a cell-wallactive antibiotic. New antibiotics have been developed for treatment of enterococci resistant to both ampicillin and vancomycin. It is difficult to prevent and control enterococcal infections. Control: careful restriction of antibiotic treatment and appropriate infection-control practices (isolation of infected patients; use of gowns and gloves by anyone in contact of patients.)