Public Policy Handout

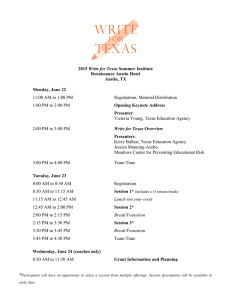

advertisement

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

WHAT IS [PUBLIC] POLICY?

Dye (1995, ix): "a combination of rational planning, incrementalism, competition between

groups, elite preferences, systematic forces, public choice, political processes, and

institutional influences" (see p. 18); (p. 2) "Public policy is whatever governments choose to

do or not do, i.e., government action and inaction; (pp. 3-4) finding a "proper" definition of

public policy has "proved futile"

Burger (1993, p. 7), citing Jenkins (1978): "'a set of interrelated decisions taken by a political

actor or group of actors concerning the selection of goals and the means of achieving them

within a specified situation where these decisions should, in principle, be within the power of

these actors to achieve'." [He critiques this definition as inadequate]

Harold Lasswell: political science demands a policy orientation -- i.e., one must ask "what is

to be done, and how is it to be done? What are the effects of doing so?"

Braman (2006, p. 66): “traditionally the word ‘policy’ has been reserved for public sector

decisions.”

Grumm, John G., & Wasby, Stephen L. (1981). The analysis of policy impact. Lexington, MA:

D.C. Heath and Company. (ix): "such an orientation [noted by Lasswell] implies treating

policy as an independent variable as well as a dependent variable, as a cause as well as a

consequence."

Nakamura & Smallwood (1980, p. 31), cited in Rist (1994, p. 548): "'A policy can be thought of

as a set of instructions from policy makers to policy implementers [sic] that spell out both

goals and the means for achieving those goals'." Rist (1994, p. 550): "Policies imply theories.

Whether stated explicitly or not policies point to a chain of causation between initial

conditions and future consequences."

Jones, Charles O. (1984). An introduction to the study of public policy (3rd ed.). Monterey, CA:

Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. (p. 26) Citing Heinz Eulau and Kenneth Prewitt: "a

'standing decision' characterized by behavioral consistency and repetitiveness on the part of

both those who make it and those who abide by it."

Majchrzak (1984, p.12): [by implication] policies are "pragmatic, action-oriented" solutions to

fundamental social problems.

Considine, Mark. (1994). Public policy: A critical approach. South Melbourne, Australia:

Macmillan. (pp. 1-2): "policy emerges from identifiable patterns of interdependence between

[sic] key social actors such as parties, corporations, unions, professions, and citizens. . . .

Public policy is one of the central processes through which our communities respond to

major social, economic and environmental problems." (p. 3) "policy, then, may be expressed

as any or all of these three things: clarifications of public values and intentions; commitments

of money and services; or granting of rights and entitlements."

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

1

(p. 3) "A public policy is an action which employs governmental authority to commit

resources in support of a preferred value."

But he challenges this definition as instrumental and antisocial, because it says little about

"the origin and consequences of policy." In his critical approach (p. 4), "policy is the

continuing work done by groups of policy actors who use available public institutions to

articulate and express the things they value."

Considine expands his definition further (p. 254): "solutions [to public problems] must come

through continuing, institutional mechanisms that link values, authority and resources. . . . a

form of structured innovation in which there is:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

A systematic application of human ingenuity and democratic values

A recognition of the key role of social conflict

Concerted negotiation among all those affected

Reorganisation of public and private resources, and

Reconsideration of the values which determine the allocation of those resources."

(p. 269): "Policy making, when considered as a system of innovation among linked or

interdependent actors, becomes a learning and regulating web based upon continuous

exchanges of information and skill." (p. 270): "The policy-as-learning perspective is therefore

an inevitably shared experience in which actors require continuing opportunities to develop

joint strategies."

Overman & Cahill (1990, p. 804): "policy formulation is the process working within a

normative structure to resolve value conflicts."

Lindblom & Woodhouse (1993, p. 7) both a result of rational discussion and political forces;

(p. 11) making policy is "a complexly interactive process without beginning or end," but (p.

122) there is no effective competition of ideas, hegemony and inertia obtain; (p. 127)

government "solutions for social problems," but there are "grave deficiencies in social

problem solving . . . due to deep and enduring features of political-economic processes" (p.

141).

Hogwood & Gunn (1984, pp. 13-19): policy is a label for a field of activity, an expression of

general purpose or desired state of affairs, specific proposals, decisions of government,

formal authorization, a programme, output, outcome, a theory or model, and process.

They go on (pp. 19-24) to define public policy, reflecting the various ways in which the term

is used and intended by others, in multiple ways: policy is to be distinguished from

"decision," policy is less readily distinguishable from "administration," policy involves

behaviour as well as intentions, policy involves inaction as well as action, policies have

outcomes which may or may not have been foreseen, policy is "a purposive course of action

but purposes may be defined retrospectively," policy arises from a process over time, policy

involves intra- and inter-organizational relationships, public policy involves a key but not

exclusive role for public agencies, and policy is subjectively [sic] defined.

Guba (1984, p. 70) states unequivocally that “[i]t is nonsense to ask the question ‘What is the

real definition of policy?’” [emphasis in the original]. He adds (pp. 63-65): "one can safely

conclude that the term policy is not defined in any uniform way; indeed the term is rarely

defined at all.” He offers eight uses of the term:

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

2

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Policy is an assertion of intents or goals.

Policy is the accumulated standing decisions of a governing body . . . within its sphere of

authority.

Policy is a guide to discretionary action.

Policy is a strategy undertaken to solve or ameliorate a problem.

Policy is sanctioned behavior, formally . . . or informally through expectations and

acceptance established over (sanctified by) time.

Policy is a norm of conduct characterized by consistency and regularity in some

substantive action area.

Policy is the output of the policy-making system.

Policy is the effect of the policy-making and policy-implementing system as it is

experienced by the client.

And he continues that “the particular definition assumed by the policy analyst determines

the kinds of policy questions that are asked, . . . data that are collected, the sources of data . . .,

the methodology . . . used, and . . . the policy products that emerge.” And reminds us that

“[f]rom the perspective of the analyst some definitions will always be better than others” (p.

70).

Eulau & Prewitt (1973, p. 465) identify the following as components of public policy:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Intentions – “true” purposes

Goals – stated ends

Plans or proposals – specified means

Programs – authorized means

Decisions or choices – specific actions

Effects – measurable impacts.

==================================================

A useful integrating concept of policy for our purposes:

Selecting goals

Selecting means of achieving them

In the context of conflicting interests and stakeholders

In the government, public action undertaken to resolve areas of public contention or

dissensus (= issue), especially about values and means of supporting them.

For most of our purposes this semester, we can think of public policy as:

(1) the commitment of public resources

(2) to certain courses of action

(3) to achieve certain goals

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

3

(4) in the context of differential power of all kinds.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

4

SOME "DEFINITIONS" OF INFORMATION POLICY

Chartrand (1986) -- a topical approach. Information policy encompasses: federal information

resources management (IRM); information technology for education, innovation, and

competitiveness; telecommunications, broadcasting, and satellite transmissions; international

communications and information policy; information disclosure, confidentiality, and the

right to privacy; computer regulation and crime; intellectual property; library and archives

policy; and government information systems, clearinghouses, and dissemination

Hayes (1985) -- a more conceptual approach: information policy is "the basis for societal and

institutional decisions concerning the allocation of resources to the acquisition, processing,

distribution and use of information"

Mason (1983) -- linked to the information lifecycle (p. 1 of Syllabus); information policy is "a

set of interrelated laws and policies concerned with the creation, production, collection,

management, distribution and retrieval of information. Their significance lies in the fact that

they profoundly affect the manner in which an individual in society , indeed a society itself,

makes political, economic and social choices."

Burger (1993) -- information policy is (p. 6) "the societal mechanisms used to control

information, and the societal effects of applying these mechanisms"; (p. 27) "the tool by which

this control [of information of various kinds] is maintained or lost, by which power is shared

or retained"; (65) an "attempt to solve information control problems." Burger, along with

others, maintains that information policy is cultural policy in that it deals with people's

behavior and values.

Hernon & McClure (1991) -- (pp. 3-4) information policy is "a field encompassing information

science and public policy, [information policy] treats information as both a commodity

adhering to the economic theory of property rights and a national resource to be collected,

protected, shared, manipulated, and managed"; (p. 4) information policy "also embraces

access to, and use of, information."

Yurow & Shaw/NTIA (1981, vi) -- information policy concerns "policies dealing with the

flow of information and with the controls which are sometimes necessary to direct that flow"

Zimmerman (in Yurow & Shaw, 1981, iv): "there is no general definition of the term

'information policy.'"

Trauth (1986) -- a systems theoretic approach; (p. 41) information policy is "the set of

activities currently in existence, which aim to achieve certain goals in the realm of

information processing and communication"; (p. 41) it is also "implicit in nature of consisting

of a collection of laws, precedents, expectations, and societal norms which are generally

autonomous and have emanated from diverse sources."

Andersen and Dawes (1991) -- "By public information policies we mean those strategies that

allow us to use information well and adapt government organizations and information

systems to a rapidly changing environment." [a public administration, "internal" view]

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

5

Heim (1986, p. 21): policies aimed at the "array of problematic dilemmas that surround

knowledge generation, as well as information access, dissemination, and storage at state,

national, and international levels of jurisdiction."

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

6

Overman & Kahill (1990) -- (p. 803) citing Weingarten (1989), "the set of all public laws,

regulations, and policies that encourage, discourage, or regulate the creation, use, storage,

and communication of information." (p. 805): "The analysis of information policy documents

produces a list of seven primary information policy values:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Access and freedom: the assumption of democracy;

Privacy: the preservation of personal rights;

Openness: the public's right to know;

Usefulness: the pragmatist's creed;

Cost and benefit: the bureaucratic necessity;

Secrecy and security: the authoritative cloak; and

Ownership: the notion of intellectual property.

Conflict and convergence over these core values establishes the normative structure of policy

conversations about national information policy design." [YES?/NO?]; (p. 813) "information

policy appears to belong to a class of policy problems, such as energy policy, industrial

policy, or welfare policy, that defy easy analysis or solution. These are policy problems in

which, 'We know that objectives invariably be distinguished by three outstanding qualities:

they are multiple, conflicting, and vague. They mirror . . . the complexity and ambivalence of

human social behavior'." (citing Wildavsky, 1979).

Bennett (1992) -- contrasts two views; on the one hand, culture is both the instrument and

object of government. On the other hand, of considerable interest to us, (p. 26) culture is a

"historically specific set of institutionally embedded relations of government in which the

forms of thought and conduct of extended populations are targeted for transformation." He

also encourages us to (p. 27), "think of culture as a historically produced surface of social

regulation." His perspective is important when we consider the relationship among power,

culture, and information.

Rowlands (1996) -- information policy exists at two levels: (1) "that which is explicit and

recorded in documentary form" and (2) "that which is expressed implicitly in the form of

habits, received wisdoms, unwritten codes of behaviour, expectations and societal norms" (p.

20). Information policy is complex, dynamic, abstract, and full of interacting conflicts and

stakeholders; thus, citing Braman, to study information policy, we need theoretical (and

methodological) pluralism, beyond disciplinary and technology-imposed limitations. Valuecritical approaches are especially needed.

Browne (1997a) – (p. 261) "How information policy is defined or its historical origins are . . .

not agreed upon." She says that we must move beyond approaches limited by topic,

discipline, and traditional areas of responsibility to focus on values and sophisticated

methods. She relies on a model of the information transfer process (see next page) to develop

what she calls the conceptual boundaries of information policy. We can use the model while

recognizing its weaknesses. In (1997b, p. 343) Browne leads us through an analysis of the

characteristics of positivism, post-positivism, critical theory, and constructivism and how that

analysis can inform the study of information policy.

Braman (1990) – (pp. 47 and 49-50) information policy is a new industry area that is

particularly prone to industry capture in the U.S. because of the strong influence of the

private sector. There is considerable confusion of goals and orientation among American

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

7

policymakers especially vis-à-vis normative questions, in part because of many and

conflicting principles (pp. 55 and 62).

Braman (2006) – (p. 70) information policy is “the domain of policy for information,

communication, and culture.” Further (xvii-xviii) information policy is “law and policy for

information creation, processing [sic], flows [sic], and use . . . . [it] fundamentally shapes the

conditions within which we undertake all other political, social, cultural, and economic

activity” [its constitutive character]. She later adds that information policy is “the

proprioceptive organ of the nation-state, the means by which it senses itself” (p. 4).

Braman, like others, notes that information policy is characterized by three elements:

1.

2.

3.

There are an “unusually large number of players, types of players, and decision-making

venues” involved in the making of information policy (p.66).

There is a great deal of “[c]onfusion about just what is and what is not information

policy” that has existed for decades (p. 67).

“Not everything that falls within the domain of information policy is labeled as such” (p.

63).

One of Braman’s useful summarizing statements is that information policy researchers face a

major intellectual challenge in “building bridges between [sic] the definitional approaches

necessary at different stages of the policy-making process” (p. 77). These definitional

approaches include (pp. 67-73):

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Lists of issue areas

Legal categories

Industries

Impacts on society

The information production chain, her preferred model.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

8

APPROACHES TO POLICY ANALYSIS

WHY STUDY PUBLIC POLICY? (Dye, 1995, 8th ed., pp. 4-6)

1.

For scientific understanding -- understanding the causes and consequences of policy

decisions improves our knowledge of society.

2.

For problem solving and professional reasons -- understanding the causes and consequences

of policy decisions permits us to apply social science knowledge to the solution of practical

problems.

3.

For political purposes and to make policy recommendations -- to ensure that the nation

adopts the "right" policies to achieve the "right" goals.

Questions in policy analysis -- "What can we learn about public policy?":

1.

Describe public policy -- a factual basis for understanding

2.

Inquire about the causes, or determinants, of public policy

3.

Inquire about the consequences, or impacts, of public policy.

As students of public policy, we can interrelate the questions in a model of the policy system.

=======================================================================

But we can consider an alternative set of reasons for doing policy analysis as suggested by

Lindblom & Woodhouse (1993):

To catalyze “debate” about social problems and policy decisions (viii)

To improve political interaction, "not to substitute for it" (p. 127)

To increase informed participation in social decision making beyond social elites (p. 137)

To break the mold of the majoritarian consensus (p. 142)

And the policy analyst must be especially alert to power relationships.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

9

MORE CONSIDERATIONS OF WHAT PUBLIC POLICY IS

From Theodoulou, Stella Z., & Kahn, Matthew A. (Eds.) (1995). Public policy: The essential

readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Theodoulou (1995a) on the contemporary language of public policy: "The student of policy

making is faced not only with a diversity of theoretical problems but also, at times, rival

vocabularies and specialist terminologies." (p. 1)

She identifies elements of a "less restrictive meaning" of public policy, a composite of other

authors' work:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

We should distinguish between what governments intend to do and what they do.

Study should include consideration of informal actors.

Public policy is not limited to formal instruments like orders and regulations.

"[A]n intentional course of action with an accomplished goal as its objective."

"[A]n ongoing process: it involves . . . the decision to enact a law . . . [and] the

subsequent actions of implementation, enforcement, and evaluation."

Theodoulou (1995b) on how public policy is made: some students of public policy are trying

to go beyond the stages of the stage framework (problem recognition and issue identification,

agenda setting, policy formulation, policy adoption, policy implementation, and policy

analysis and evaluation) that has dominated policy research for decades. (pp. 86-87)

Context helps determine policy, and context includes (1) the history of past policies; (2)

"cultural, demographic, economic, social, and ideological factors"; (3) the institutional

context; and (4) ideological conflict between "liberals and conservatives over the nature of

governmental action" (pp. 91-92)

Kingdon (1995) on agenda setting.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

"Conditions come to be defined as problems, and have a better chance of rising on the

agenda, when we come to believe that we should do something to change them." (p. 106)

Agenda setting is a "garbage can," combining streams of problems, politics, and other

elements.

Policy ideas are combined and recombined over years by "policy communities" of

specialists and decision makers.

Policy entrepreneurs link ideas to decision makers -- these entrepreneurs expend their

own resources to promote ideas.

There are "policy windows" which are structural opportunities for ideas to become part

of the agenda.

Lindblom (1995) on the "science" of muddling through, originally published in 1959:

1.

"[T]ypically the administrator chooses -- and must choose -- directly among policies in

which . . . values are combined in different ways. He cannot first clarify his {sic] values

and then choose among policies." (p. 117)

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

10

2.

3.

Usually there is a great deal of disagreement among all parties about values and

objectives, as well as the relative merits of policy alternatives.

"Policy is not made once and for all; it is made and re-made endlessly. policy-making is a

process of successive approximation to some desired objective in which what is desired

itself continues to change under reconsideration." (p. 123)

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

11

NATURE OF POLICY RESEARCH/ANALYSIS

In her book on policy research methods, Majchrzak (1984, p. 102) says:

Policy Analysis is research done by political scientists interested in the process by which

policies are adopted and the effects of the policies once adopted.

Policy Research is the process of conducting research or analysis on a fundamental social

problem in order to provide policymakers with pragmatic, action-oriented recommendations

for alleviating the problem.

I, like many others who study public policy, do not accept this dichotomy.

Majchrzak has several other assertions that are valuable for us to consider:

"Policy research is more than simply following a set of activities. . . . 'a mixture of science,

craftlore, and art.'" (p. 11)

"Policy research . . . is defined as the process of conducting research on, or analysis of, a

fundamental social problem in order to provide policymakers with pragmatic, actionoriented recommendations for alleviating the problem." (p. 12)

We can question this "problem-oriented, technicist" approach.

"policy research has both a high action orientation and a concern for fundamental social

problems." (p. 13)

"policy research efforts study fundamental social problems in an attempt to create pragmatic

courses of action for ameliorating those problems. No other type of research process has

quite the same focus or action orientation." (p. 14)

"the context of doing policy research consists of competing inputs, complex problems, and

seemingly irrational decisionmaking styles." (p. 15)

"Since the objective of policy research is to provide policymakers with useful

recommendations, policy studies tend to focus primarily on malleable variables." (p. 50)

She quotes Bernard Berelson's (1976) five criteria for determining if research questions are

likely to "advance" public policy (p. 52):

(1) The research question should address an important aspect of the social problem;

(2) The research question should be do-able – that is, feasible given expected study

constraints;

(3) The research question should be timely by providing information that will be useful for

current and future decisionmaking;

(4) The research question should provide a synthesis of diverse viewpoints so that the

results represent an integration to the field, rather than simply an addition

(5) The research question should exhibit policy responsiveness by addressing issues in a

manner that will help policymakers act on the social problem.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

12

MORE ON THE NATURE OF POLICY RESEARCH/ANALYSIS -- PER DOTY

Another useful summary for considering what the study of public policy entails may be to

consider such study as:

Action-oriented

Concerned with identifiable social issues, conflicts, and questions [avoiding locution of

"social problems" and resulting technicist approach to their "solution"]

Value-laden

Only one of many factors in a policy decision

Often concerned with DEFINITION, not "solution," of a social conflict

Often inherently controversial

Dependent on the academic discipline of the researcher/analyst and its assumptions about:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

What questions are answerable

What answers are acceptable/reasonable/feasible

What methods of investigation and presentation are appropriate

What forms of evidence are convincing

What kinds of rhetoric are most persuasive and most appropriate for policy

argumentation

What role policy analysis should play in policy formation

Which stakeholders are of primary importance

Why a researcher does an analysis.

Among the many disciplines that study information policy are:

Information studies

Law

Cultural Studies

Public Affairs

Public Administration

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

Communication

Political History

Rhetoric & Comp

Sociology

MIS

Economics

Political Science

Ethnic Studies

Area Studies

Organizational Studies.

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

13

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SUCCCESSFUL POLICY ANALYST

(Doty, 1998; some from House, 1982; Ballard et al., 1981; and Majchrzak, 1984)

Ability to communicate well in writing and orally

Management skills -- to write and evaluate proposals and research studies, to manage

personnel, to prepare and follow budgets, and to develop and adhere to realistic schedules

Problem solving abilities -- to combine creativity, intelligence, experience, and

responsiveness to others and the environment

Contacts -- with policy makers and their staffs, with other analysts, with citizens, and with

important interest groups in the private and public sectors

Political understanding -- an appreciation of stakeholders' limitations and constraints, the

context for decision making, and the importance of precedent in public life

A vision for the implementation of policy recommendations

Skills in consensus building and cooperative work, often in interdisciplinary and stressful

situations

Ability to recognize and analyze a moving target

Appropriate academic training in concepts, methods, data handling, and so on

Experience in decision-making

An ability to combine microscopic and macroscopic views of the problem, especially to

develop and use an understanding of the contexts of policy issues

Experience in the use of both qualitative and quantitative research techniques

Ability to create and articulate clear models and constructs to a variety of stakeholders and

audiences.

But we get a warning from Lindblom and Woodhouse (1993, pp. 5-10) that there are four major

influences on policymaking and policy analysis that are often ignored in positivistic, "linear"

models of policy making:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Conceptual and cognitive limitations

Tension between rationalism and the political process

Influence of business

Social inequity, since differential power relationships are an essential environmental factor.

Therefore, the analyst must "challenge fundamental features of politics, economics, and culture"

(p. 136). Do you agree or disagree? Why?

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

14

MULTIPLE ROLES OF THE SOCIAL SCIENTIST

Drawn largely from Ballard et al. (1981) on social science and social policy; be a bit wary of their

unreflective use of the problem locution. The social scientist studying public policy must be a:

1.

Substantive expert -- "become familiar with the policy system that influences the particular

problem at hand" (p. 181), including competing definitions of the problem, its historical

development, stakeholders, and its social and economic implications

2.

Information processor -- "selecting, integrating, and synthesizing existing knowledge about

particular problems, impacts, and policy alternatives" (p. 181); NOT synonymous with a lit

review, rather applying knowledge from a variety of disciplinary and stakeholder

perspectives

3.

Disciplinary scholar -- "the researcher as scholar/practitioner" (p. 182), grounded in one's

discipline (especially methods and criteria of quality, e.g., reliability and validity), but able to

go beyond disciplinary boundaries because policy problems are not in neat disciplinary

niches

4.

Change agent -- "Disagreement exists regarding whether or how actively researchers should

pursue this role and how certain important ethical questions that become apparent should be

resolved." (p. 184)

Such Q's arise as the analyst and the user of the analysis get closer. These concerns center on

determining the course of the research, organizational resistance to "bad news," "pathology of

trust" (despite a close working relationship with study sponsors, maintaining high standards

for analysis), and misused information.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

15

INFORMATION POLICY VALUES

From Overman & Cahill (1990) on value in information policy analysis.

"The analysis of information policy documents produces a list of seven primary information

policy values:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

access and freedom: the assumption of democracy;

privacy: the preservation of personal rights;

openness: the public's right to know;

usefulness: the pragmatist's creed;

cost and benefit: the bureaucratic necessity;

secrecy and security: the authoritative cloak; and

ownership: the notion of intellectual property."

These values give us insight into the "normative structure of information policy" [what does

"normative" mean? what is its antonym?] (adapted from Overman and Cahill, 1990, Table 2).

Perspective

V

a

l

u

e

s

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

Restrictive

Distributive

Usefulness

Cost and Benefit

Secrecy and Security

Ownership

Privacy (protection)

Access

Freedom

Privacy (access)

Openness

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

16

TRADITONAL MODELS OF “THE POLICY PROCESS”

As noted in your readings and we have already discussed in class, there are many critiques of the

traditional, process-oriented, problem-centric approach to policy studies. At the same time,

however, we need to recognize the strengths of these models and appreciate their overarching

influence in the various policy literatures. Critical, value-sensitive perspectives are slowly but

surely undermining the “steps-in-the-policy-process-to-solve-social-problems” approach, but the

traditional perspective continues to have enormous influence, especially implicitly. Here are

some examples of that traditional point of view. Also see Majchrzak (1984).

•

Jones, Charles O. (1984). An introduction to the study of public policy (3rd ed.). Monterey, CA:

Brooks/Cole.

pp. 27-28

1.

Perception/definition

What is the problem to which this proposal is directed?

2.

Aggregation

How many people think it is an important problem?

3.

Organization

How well organized are these people?

4.

Representation

How is access to decision makers maintained?

5.

Agenda setting

How is agenda status achieved?

6.

Formulation

What is the proposed solution? Who developed it and how?

7.

Legitimation

Who supports it[,] and how is majority support maintained?

8.

Budgeting

How much money is provided? Is it perceived as sufficient?

9.

Implementation

Who administers it[,] and how do they maintain support?

10. Evaluation

Who judges its achievements and by what methods?

11. Adjustment/ termination

What adjustments have been made[,] and how did they come

about?

Theodoulou, Stella Z. (1995b, pp. 86-87) on how public policy is made:

1.

Problem recognition

2.

Policy adoption

3.

Policy implementation

4.

Policy analysis and evaluation

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

17

REFERENCES

Andersen, David F., & Dawes, Sharon S. (1991). Government information management: A primer

and casebook. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ballard, Steven C., Brosz, Allyn R., & Parker, Larry B. (1981). Social science and social policy:

Roles of the applied researcher. In John G. Grumm & Stephen L. Wasby (Eds.), The analysis of

policy impact (pp. 179-188). Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath & Co.

Bennett, Tony. (1992). Putting policy into cultural studies. In Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson,

& Paula Treicher (Eds.), Cultural studies (pp. 23-37). New York: Routledge.

Braman, Sandra. (1990). The unique characteristics of information policy and their U.S.

consequences. In Virgil L.P. Blake & Renee Tjoumas (eds.), Information literacies for the twenty-first

century (pp. 47-77). Boston: G.K. Hall.

Braman, Sandra. (2006). Change of state: Information, policy, and power. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Browne, Mairéad. (1997a). The field of information policy: 1. Fundamental concepts. Journal of

Information Science, 23(4), 261-275.

Browne, Mairéad. (1997b). The field of information policy: 2. Redefining the boundaries and

methodologies. Journal of Information Science, 23(5), 339-351.

Burger, Robert H. (1993). Information policy: A framework for evaluation and policy research.

Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Chartrand, Robert. (1986). Legislating information policy. Bulletin of the American Society for

Information Science, 12(5), 10.

Considine, Mark. (1994). Public policy: A critical approach. South Melbourne, Australia:

Macmillan.

Doty, Philip. (1998). Why study information policy? Journal of Education for Library and

Information Science, 39(1), 58-64.

Dye, Thomas R. (1995). Understanding public policy (8th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice

Hall.

Eulau, Heinz, & Prewitt, Kenneth. (1973). Labyrinths of democracy. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Grumm, John G., & Wasby, Stephen L. (1981). The analysis of policy impact. Lexington, MA: D.C.

Heath.

Guba, Egon G. (1984). The effects of definitions of policy on the nature and outcomes of policy

analysis. Educational Leadership, 42(2), 63-70.

Hayes, Robert M. (Ed.). (1985). Introduction. Libraries and the information economy of California (pp.

1-49). Los Angeles: University of California at Los Angeles.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

18

Heim, Kathleen. (1986). National information policy and a mandate for oversight by the

information professions. Government Publications Review, 13(1), 21-37.

Hernon, Peter, & McClure, Charles R. (1991). United States information policies. In Wendy

Schipper & M. Cunningham (Eds.), National and international information policies (pp. 3-48).

Philadelphia, PA: National Federation of Abstracting and Information Services.

Hogwood, B.W., & Gunn, L.A. (1984). Policy analysis for the real world. Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press.

House, Peter W. (1982). The art of public policy analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Jones, Charles O. (1984). An introduction to the study of public policy (3rd ed.). Monterey, CA:

Brooks/Cole Publishing.

Kingdon, John W. (1995). Agenda setting. In Stella Z. Theodoulou & Matthew A. Cahn (Eds.),

Public policy: The essential readings (pp. 105-113). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lasswell, Harold. (1951). The policy orientation. In Daniel Lernet & Harold Lasswell (Eds.), The

policy sciences (pp. 3-15). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lindblom, Charles E. (1995). The science of “muddling through.” In Stella Z. Theodoulou &

Matthew A. Cahn (Eds.), Public policy: The essential readings (pp. 113-127). Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall. (Original work published 1959)

Lindblom, Charles E. (1979). Still muddling, not yet through. In Democracy and the market system

(pp. 237-259). Oslo: Scandinavian Press.

Lindblom, Charles E., & Woodhouse, Edward J. (1993). The policy-making process (3rd ed.).

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Majchrzak, Ann. (1984). Methods for policy research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mason, Marilyn Gell. (1983). The federal role in library and information services. White Plains, NY:

Knowledge Industry Publications.

Nakamura, R.T., & Smallwood, F. (1980). The politics of policy implementation. New York: St.

Martin’s.

Overman, E. Sam, & Cahill, Anthony G. (1990). Information policy: A study of values in the

policy process. Policy Studies Review, 9(4), 803-818.

Rist, Ray C. (1994). Influencing the policy process with qualitative research. In Norman K.

Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 545-557). Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Rowlands, Ian. (1996). Understanding information policy: Concepts, frameworks and research

tools. Journal of Information Science, 22(1), 13-25.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

19

Theodoulou, Stella Z. (1995a). The contemporary language of public policy: A starting point. In

Stella Z. Theodoulou & Matthew A. Cahn (Eds.), Public policy: The essential readings (pp. 1-9).

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Theodoulou, Stella Z. (1995b). How public policy is made. In Stella Z. Theodoulou & Matthew

A. Cahn (Eds.), Public policy: The essential readings (pp. 86-96). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall.

Theodoulou, Stella Z., & Cahn, Matthew A. (Eds.). (1995). Public policy: The essential readings.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Trauth, Eileen M. (1986). An integrative approach to information policy research.

Telecommunications Policy, 10(1), 41-50.

Weingarten, F. W. (1989). Federal information policy development: The Congressional

perspective. In Charles R. McClure, Peter Hernon, & Harold Relyea (Eds.), United States

government information policies: Views and perspectives (pp. 77-99). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Wildavsky, Aaron. (1979). Speaking truth to power: The art and craft of policy analysis. Boston:

Little, Brown.

Yurow, Jane H., Shaw, Helen A. (1981). Issues in information policy. Washington, DC: National

Telecommunications and Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce.

INF 390N.1

Federal Information Policy

Philip Doty

School of Information

University of Texas - Austin

20