stroke

advertisement

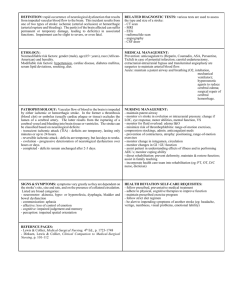

CEREBRO-VASCULAR DISEASE & STROKE Faizan Zaffar Kashoo CEREBRO-VASCULAR DISEASE & STROKE Stroke is the commonest cause of death in developed countries. Hypertension is the most treatable risk factor. Thromboembolic infarction (80%), cerebral and cerebellar haemorrhage (10%) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (about 5%) are the major cerebrovascular problems. DEFINITIONS Stroke is defined as the clinical syndrome of rapid onset of cerebral deficit (usually focal) lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than a vascular one. Completed stroke means the deficit has become maximal, usually within 6 hours. Stroke-in-evolution describes progression during the first 24 hours. Minor stroke. Patients recover without significant deficit, usually within a week. Transient ischemic attack (TIA). This means a focal deficit, such as a weak limb, aphasia or loss of vision lasting from a few seconds to 24 hours. There is complete recovery. The attack is usually sudden. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY COMPLETE STROKE One of three mechanisms is usual: arterial embolism from a distant site arterial thrombosis haemorrhage into the brain (intracerebral or subarachnoid). Less commonly: venous infarction polycythaemia (hyperviscosity syndromes) fat and air embolism multiple sclerosis mass lesions (e.g. brain tumour, abscess, subdural haematoma) Modifiable risks Cardiovascular Disease Hypertension CAD Diabetes Dyslipidemia High total Cholesterol and/or Low HDL Atrial Fibrillation Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis Cigarette smoking Sickle Cell Disease Dietary Factors Obesity Physical Activity Hormone Replacement Therapy Types of stroke Ischemic stroke syndrome Hemorrhagic stroke syndrome Ischemic Stroke Syndrome Lacunar Infarction Infarction of small penetrating arteries in pons and basal ganglia Associated with chronic HTN present in 80-90% Pure motor or sensory deficits Ischemic Stroke Syndromes Basilar Artery Occlusion Severe quadriplegia Coma Locked-in syndrome-complete muscle paralysis except for upward gaze Ischemic Stroke Syndromes Vertebrobasilar Syndrome Posterior circulation supplies brainstem, cerebellum, and visual cortex Dizziness, vertigo, diplopia, dysphagia, ataxia, cranial nerve palsies, and limb weakness, singly or in combination HALLMARK: Crossed neurological deficits: ipsilateral CN deficits with contralateral motor weakness Ischemic Stroke Syndromes Middle cerebral artery occlusion Dominant Hemisphere (usually the left) Contralateral weakness/numbness in arm and face greater than leg Contralateral hemianopsia Gaze preference toward side of infarct Aphasia (Wernicke’s -receptive, Broca’s -expressive or may have both) Dysarthria Ischemic Stroke Syndromes Middle cerebral artery occlusion Nondominant hemisphere Contralateral weakness/numbness in arm and face greater than in the leg Constructional Apraxia Dysarthria Inattention, neglect, Ischemic Stroke Syndromes Anterior Cerebral Artery Infarction Contralateral weakness/numbness greater in leg than arm Dyspraxia Speech perseveration Slow responses Acute stroke: immediate care, and thrombolysis Paramedics and members of the public are encouraged to make the diagnosis of stroke on a simple history and examination – FAST: ■ Face – sudden weakness of the face ■ Arm – sudden weakness of one or both arms ■ Speech – difficulty speaking, slurred speech ■ Time – the sooner treatment can be started, the better. Dedicated units with multidisciplinary, organized teams deliver higher standards of care than a general hospital ward Investigations The purpose of investigations in both stroke and TIA is: to confirm clinical diagnosis to distinguish between haemorrhage and thromboembolic infarction to look for underlying causes of disease and to direct therapy, either medical or surgical Imaging TIA & stroke patients Imaging TIA and stroke patients CT and MRI. CT imaging will demonstrate haemorrhage immediately while a patient with an infarct may have a normal scan. Infarctions are usually detectable at 1 weeK although 50% are never detected on CT. CT or MRI should be carried out urgently in the majority of cases. Diffusionweighted imaging (DWI) MR can identify infarcted areas within a few minutes of onset. Conventional T2 weighting is no better than CT. Imaging will also show the unexpected, e.g. subdural haematoma, tumour or abscess. Further investigations Routine bloods (for polycythaemia, infection, vasculitis, thrombophilia, syphilitic serology, clotting studies, autoantibodies, lipids) Chest X-ray ECG Carotid Dopplers Angiography Management of cerebral infarction The possible sources of embolus should be sought (e.g. carotid bruit, atrial fibrillation, valve lesion, evidence of endocarditis, previous emboli or TIA) Assess hypertension and postural hypotension The brachial blood pressure should be measured in each arm; a difference of more than 20 mmHg is suggestive of subclavian artery stenosis. The neurological deficit should be carefully documented. Immediate management Admit to multidisciplinary hospital stroke unit if possible. General medical measures Care of the unconscious patient, Oxygen by mask, Assessment of swallowing, Check BP and look for source of emboli. Immediate brain imaging is essential. Cerebral infarction : If CT shows infarction, give aspirin (300 mg/day initially) antiplatelet therapy if no contraindications, give alteplase thrombolysis, which must be started within 3 hours (aim for 90 min) of stroke; informed consent is essential. Cerebral haemorrhage: If CT shows haemorrhage, do not give any therapy that may interfere with clotting. Neurosurgery may be required. Surgical treatment Internal carotid endarterectomy: Surgery is recommended in TIA or stroke patients shown to have internal carotid artery stenosis greater than 70%. Successful surgery reduces the risk of further TIA/stroke by approximately 75%. Endarterectomy has a mortality around 3%, and a similar risk of stroke. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (stenting) is an alternative procedure. Prognosis Twenty-five per cent of patients die within 2 years of a stroke. Around 30% of this group die in the first month Gradual improvement usually follows stroke, although the late residual deficit may be severe. Of those who survive, about one-third return to independent mobility and one-third have serious disability requiring permanent institutional care. Medical management and pharmacological consideration 1. Thrombosis and TIA 80% to 100% die in few minutes Improve circulation tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) heparin (anticoagulant drugs) warfarin Clot prevention aspirin, dipyridamole and sulfinptrazone Surgical treatment (remove clot from artery) Thromboendarterectomy Medical management and pharmacological consideration Embolic infarction 2. • Emphasis on prevention Similar to thrombotic infarction Anticoagulant therapy Medical management and pharmacological consideration 3. Hypertensive hemorrhage Control hypertension Medical management of associated problems SPASTICITY PHARMACOLOGICAL 1. Centrally acting drug diazepam 2. Peripherally acting drug Procaine Phenol Botalulinum toxin A Baclofen SURGICAL TREATMENT 1. 2. Tenotomy Neurotomy Medical management of associated problems SEIZURES Thrombotic and embolic stroke – early onset Hemorrhagic stroke – late onset Drugs Phenytoin Carbamazepine Medical management of associated problems Respiratory involvement Fatigue – respiratory inefficiency 50% more O2 than normal Decrease lung volume Medical management of associated problems TRAUMA Falls – improper balance Hip wrist and humerus fracture are common Osteoporosis . Medical management of associated problems THROMBOPHLEBITIS Clot formation Common in weaker leg Medical management of associated problems REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY Sympathetic blockers Oral or intramuscular corticosteroids STAGES OF RECOVERY Cerebral shock Immediately after cerebral ischemia Last between few hrs to days Recovery phase Flaccid stage Recovery stage Severe sensory loss and muscle is flaccid Tone improves Distal parts recover first Spasticity of stage Proximal spasticity appears Limbs in synergetic pattern (atypical pattern) UL in flexion and LL in extension pattern Factors that influence the recovery Quality of the rehabilitation treatment. The motivation of the patient and his family. Age of the patient. Persistence of the flaccid stage and delay in treatment. Evaluation It the process of Collecting information to establish a baseline level of performance to plan intervention and progress. Components of evaluation Level of consciousness Mental status examination Cranial nerve examination Sensory examination Motor and reflex examination Gait examination Functional tests Prognosis Short and long term goals intervention Evaluation of primary impairments Active movements 70 – 80 % of stroke patient have weakness. Weakness and control is assessed. Timing of muscle firing. Sequence of movement. Speed of movement. Do not assist the client. Evaluation of primary impairments Assisted movements Correct alignment to gather additional information Assist weak muscles Stabilize joint and document the pattern of movement Evaluation of primary impairments Tone Modified ashworth scale Equilibrium and protective reactions Equilibrium reactions are assessed while slowly moving the part away from base of support Protective reactions by hopping or stepping and positive support Evaluation of secondary impairments Loss of joint range and muscle shortening Poor alignment Muscle activation problem Functional consequence of two joint muscle. Eg: gartrocsoleus Evaluation of secondary impairments Pain Visual analog pain rating scale McGill pain questionnaire Shoulder pain Functional evaluation Activity of daily living Barthel index Motor assessment scale Function independence measure Motor function and balance Fugl Meyer scale Berg balance scale Functional reach Recognizing needs What movement and function is possible? What movement and function are not possible? How do primary and secondary impairment relate to functional performance? Goal setting Functional goal Stand independently and perform grooming activity Short term goal Client will length hamstring and plant foot flat on the ground while standing Long term goal Able to perform most of the functional activities Choosing intervention Two school of though Use normal side Use affected side Using both will benefit the patient Impairment based intervention Common impairment and suggested interventions WEAKNESS AND LOSS OF CONTROL Trunk control First Level- basic trunk movements in 3 planes. Second level- trunk movement with extremity movement. Extremity control Weight bearing and assisted movements. Distal re-education. Common impairment and suggested interventions MUSCLE ACTIVATION DEFICIT Improper initiation Uses proximal more than distal Inappropriate muscle selection Uses stronger than weaker Inappropriate sequencing Co-contraction and out of sequence Excessive force production Inappropriate effort during movement Common impairment and suggested interventions HYPOTONICITY Quick icing. Quick stretch in mid range. Weight bearing. Proper alignment. Mild stretching at the end of range. Common impairment and suggested interventions HYPERTONICITY Proximal instability Improve stability of upper trunk – decrease arm hypertonicity Poor joint alignment Stretching of gastronemius and soleus – active. During activity Proper sequence of activity Inhibition of spastic pattern is wrong. Common impairment and suggested interventions Toe posturing Toe clawing Poor alignment Toe curling Instability of trunk and leg Common impairment and suggested interventions LOSS OF ALIGNMENT TRUNK Atypical starting position for functional activity. Shortening towards affected side. Forwards flexion of trunk. Rotation towards affected side. Functional activity Supine Bridging Rolling – Task oriented Kneeling – Task oriented Transition activity Feeding Reach and grasp Half kneeling Standing Walking Side walking Therapies to hand Activation of abductor digiti minimi First dorsal interrosei Postural asymmetry Changing the orientation from horizontal to vertical support Trunk extension facilitation Sit to stand Orientation to Mid line