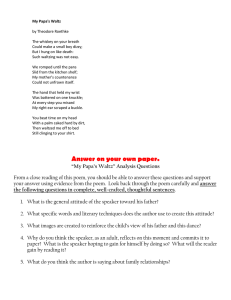

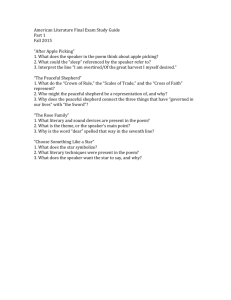

Romantic Poems

advertisement