Höft H S0045802 Bachelorthese

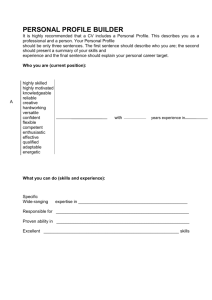

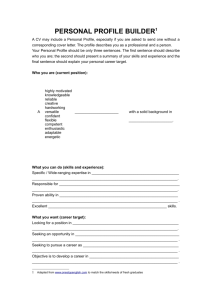

advertisement