Capstone-JGB V.2

advertisement

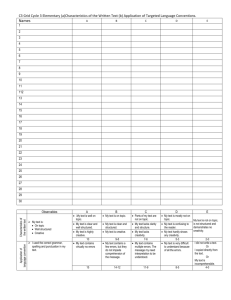

Fostering Creativity in the Music Classroom by John Ballard Submitted to the Capstone Committee at Vanderbilt University April 14, 2009 Abstract Creativity is central to the human experience and the evolution of thought and ideas. It must be recognized as an approachable subject and actively pursued in educational settings. Many subjects that are well-suited for fostering creativity are often more influenced by the performance-based atmosphere pervading much of our educational system than they are aware. The focus must shift from the easily assessed product to the process. We must explore the subjective. In the classroom students learn fingerings and perform dynamics, but are rarely invited to make decisions themselves or explore their own possibilities. Through my experiences as a prospective music teacher, active musician, Graduate Student at Peabody College, and recent researcher of creativity, I am offering my considerations and ideas as to how we might identify and strengthen our students' creativity, or ability to think divergently in the music classroom. Ballard 2 Introduction Creativity has been researched for almost as long as we have recorded history. There are many variations on a common idea of its definition. After exploring creativity and the creative process in music, I have come to adopt a relatively simple definition for my own use: Creativity is the aptitude to create something unique within the experience of an individual from previously unrelated knowledge or ideas. Because of creativity in music, for example, we have a "family tree" of music within which divergent branches can be contributed to particular musicians' unique combinations of experiences and influences. William Grant Still is one of the earliest examples of the blending of AfricanAmerican musical traits and Western structure and composition. Both forms of music existed independently prior to his career as a musician, but he brought them together through his engagement in the creative process. When we speak of fostering creativity such as this among our students, we're asking them to assess their own knowledge that is relevant to a particular assignment or goal and to find a divergent path. In writing about creativity, John Baer (1993) refers heavily to the path of divergent thought (pp. 46). This essay focuses on the presentation of creativity as it relates to finding an appropriate "divergent, yet related, path." This means following a path that utilizes more commonly known ideas while diverging through the manipulation of other variables. Creativity as divergence is strongly present in middle school Band or Strings classes when addressing improvisation. Prior to improvising, students are presumably familiar with the notes on the instrument and the meter of the piece. They should also Ballard 3 be familiar with a basic background progression of chords, or harmonic structure. These are the known variables that account for "the related" part of the path, or product. In my practica and student teaching experiences, the point at which students usually begin to diverge may be when they start making their own rhythms on one pitch or using a single rhythm while experimenting on varying pitches. This is one illustration in the music classroom to which a "divergent, yet related, path" may refer. Music education can provide a wonderful situation in which to help our students reclaim their creativity. The current atmosphere surrounding American public education, though, focuses on the "core" academic subjects. Nationally, pressure is applied to schools to perform well in these core subject areas on standardized tests. Schools must do this in order to maintain their status, prestige, and most of all, their funding, to the detriment of music education programs. With contests and other, more tangible assessments of music, however, the focus of music education has followed the national atmosphere of public education in its pursuit of testing and performance. In my observations, through my education with Vanderbilt's Peabody Teacher's School, of Nashville area music programs, the most obvious goal is often a "superior" rating at music festivals. Participation in these events and analysis of how to succeed at them commonly receive the bulk of long-term planning from music curriculums. A national study by Bruce Abril (2006) that utilized a sample size of 350 elementary school principals concluded that almost half of the principals felt that the implementation of “No Child Left Behind” negatively impacted the focus of music education in their schools. Approximately one third of them felt that the presence of Ballard 4 standardized testing negatively impacted their music education programs. In follow-up questions provided to these principals, much of the negative impact from NCLB and standardized testing is reported to come from their effect on scheduling and on funding. Later in this essay we will create the perspective from which music educators may foster creativity in an atmosphere greatly affected by NCLB. In Nashville, Tennessee, we are familiar with this atmosphere since our metropolitan school system is currently under the legal auspices of The State of Tennessee for failure to meet the goals and testable academic requirements set forth by the “No Child Left Behind” Act. Dr. Timothy Sullivan (2006-2), of Toronto's Northern College, refers to the educational atmosphere that often results from this type of situation as that of "skill transfer," as opposed to "creative" education (p. 23). Many music programs follow this trend toward "skill transfer." In a musical ensemble, this means working toward technical proficiency on instruments or voices. American music education has been focused primarily on performance for approximately the last one hundred years, according to Bennet Reimer (1997), who has held prominent positions such as the Chair of the Music Education Department at Northwestern University. He believes that we have been teaching our students primarily how to “sing and play,” once they are beyond elementary school (p. 33). Reimer’s viewpoint is shared by Bruce Adolphe (1991). He puts it succinctly: “A good technique serves the imagination and is not noticed" (Introduction). As Reimer and Adolphe may have predicted, most instrumental music students I have observed omit the creative process to a significant degree in a focus on technical Ballard 5 mastery of their instrument. Students are not often offered the opportunity to engage their ability to be creative in making decisions about a piece and, as Adolphe says, to allow their "good technique to serve their imagination[s]." Music education in the United States, in all facets of the students' experiences, has largely been focused on the rehearsal process. This method is teacher-directed sequential instruction, coupled with repetitive student practice, and the regular testing of rote skills (Sullivan, 2005-1, p. 24). Yet, if we take Reimer’s perspective seriously, we have shortchanged the creative perspective, and we have allowed the situation to worsen in the current environment of emphasis on “core” subjects. How has this happened, if creativity is an essential ingredient to the arts? We can, through music education, reintroduce creativity into our arts education and into the schools. Learners and Learning If creativity includes the pairing of previously unrelated experiences or knowledge, then any class that offers students the opportunity to include other subjects must be an effective vehicle for exploring creativity. The study and performance of music may help students tie together other subjects. In a single rehearsal, a music teacher can address the historical or social contexts surrounding the creation or premiere of a piece. Many works are even used to describe art or poetry. Discussing the counting of rhythm is very mathematical and provides students another angle from Ballard 6 which to look at math content. In a setting such as this, students are offered many more opportunities from which to form unexpected associations. My student teaching mentor teacher from J. T. Moore Middle School, Genevieve Simons, has found interesting ways to exploit the ability of music education to incorporate other subjects. With reference to NCLB, this school has identified writing as an area that requires improvement for all grades. Ms. Simons regularly includes openended writing assignments for listening and practicing. This provides continuity for the student across subjects and reinforces the school's goals while providing another perspective from which to achieve those of her curriculum. Creativity in music is accessible to all students, not just musicians. Expression, as well, is not exclusive to trained musicians. In a study, L. Daignault (1997) determined that the ability to play the piano had no significant correlation to compose for the piano, given that all participants were provided with the limitations of the instrument. Students of all levels of education have the capacity for creativity and expression and the ability to expand these through experience, exploration, and guidance. It is possible for teachers to label some students, especially in middle school, as obviously creative and to assume that others who have not demonstrated their creative abilities have, in fact, less creative ability. Middle school students tend to be the most difficult to manage and they are beginning to seriously assume academic and athletic interests. Because creativity can be developed and nurtured, teachers with this perspective could inadvertently limit some students by "writing them off” (Sullivan, 20052, p. 32). Ballard 7 In my classroom experience at J. T. Moore, it has become very clear that “good behavior” is not strongly related to creativity or intelligence. I have observed that often, intelligent students are the same ones that are constantly speaking out of turn and breaking other classroom procedures. However, when they complete their work, many of these students often produce creative or interesting products. These students are very anxious or excited and gain their reputation for ignoring classroom procedures from the start (Sullivan, 2005-2, p. 32). Disruptive behavior can be very frustrating to a teacher and it is understandable how these students might quickly find themselves on the teacher's "bad side." They commonly gain labels such as "nonconformist," "impulsive," and "likes to be alone." They are rarely labeled as "practical," "dependable," or "logical" (Sullivan, 2005-2, p. 33). Participation in music offers students the opportunity to form unique cognitive connections as well as inter-subject connections. Since the performance of music often requires students to address both objective and subjective concerns, it can simultaneously stimulate both sides of a student’s brain. Donald Hodges (2000), Director of the Institute for Music Research and Coordinator of Music Education at The University of Texas as San Antonio, concludes that “music is not represented just in the right or left side of the brain, but all over the brain… musical processing [involves] widely diffuse areas of the brain” (p. 20). Despite the current results oriented atmosphere, the musical curriculum's role in developing students' creativity is an integral part of their education. Ballard 8 Learning Environment The main difference between various artistic opportunities for creativity is the set of constraints placed upon them (Priest, 2001, p. 247). An illustration of this may be found by contrasting painting and music. Painting involves such variables as type of stroke, type of paint, size of canvas, and thickness of brush. Music is characterized by instrumentation, rhythm, dynamics, and pitch. If we ask our students to create in music, we must recognize the realm of music as a series of constraints, then modify them as variables that define our playing field. It can be overwhelming to stare at a blank canvas with the intention to create, but as we start to provide some constraints or focused direction, such as a subject or type of brush stroke to be used, it becomes easier to fill the gaps with our own divergent ideas. We must set up the understanding of these variables with our students, so that we can provide them with different situations from which to create with minimal explanation. These variables or constraints must also be referred to as directions or ideas that help to guide, not to hold back as the word constraint implies. In some classrooms, students do not have access to the ideal supplemental materials with which to participate in music-making. Implementing creativity, however much would benefit from them, does not require any additional supplies. I recently observed Shane Kimbro, a Metro middle school band teacher, work with students on creating rhythms using types of pie to represent different rhythmic values. For instance, a quarter-note, which receives one beat, was represented by the word "pie." Two Ballard 9 eighth notes, which evenly divide the quarter note by two, were represented by the word "apple," pronounced "ap-ple." The students were later invited to create other ways to represent note values. Creativity can be implemented in lesson plans regardless of funding or the presence of supplemental materials. Creativity must contain: "An openness to experience: extensionality. This is the opposite of psychological defensiveness…In a person who is open to experience; each stimulus is freely relayed through the nervous system, without being distorted by any process of defensiveness." -Carl Rogers Students must be willing to accept new or different ideas. They will benefit greatly from moving outside of their "comfort zone." During student teaching at a middle school here in Nashville, I made a point to start each General Music class session with listening to music. The listening selection would usually be unfamiliar to the students. The goal, though, was to provide scaffolding for the students to begin to understand and associate themselves with the music. We tried to, As Mitchell Korn (2009), of the Nashville Symphony's education department says, "provide them a way in.” In one of the classes, a student asked, rather confrontationally, "Why we gotta listen to this?" I explained to the class that each of them had a “comfort zone” and that consistently experiencing new forms of music would expand their musical “comfort zone.” As Dr. Timothy Sullivan (2006-1) says, "One of the characteristics that improve creativity is to experience widely and intensely, to read outside of one's discipline, to Ballard 10 move outside of your 'comfort zone’ (p.24). It must be understood that the students will experience new forms of music and ideas from which they will be provided the opportunity to relate them back to their prior knowledge and experience. After relating the listening of new music to the real world in which they function, all of the students seemed a little more open to the idea of listening to something new. They listened again to the music that was playing prior to the student's question and proceeded to ask questions about it before we went on with the planned lesson. As mentioned earlier in this essay in the Learners and Learning section, creative music-making is intrinsically motivated and enacted through the process, not the product. In a 1984 study done by Richard Koestner et al. (1984), intrinsic motivation was linked to greater creativity (p. 606). The use of intrinsic motivators is “central to foster a child’s self-direction in music. Extrinsic motivators… can be overused and draw students’ attention away from the lasting benefits of learning music” (CEDFA). All too often, directors forget that the decision making process cannot be exclusive to them if they want to develop creative musicians. "I don't play accurately -- anyone can play accurately -- but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte." -Oscar Wilde Performing musically, or creatively, and performing accurately are related, but not synonymous. Oscar Wilde presents this idea simply: "I don't play accurately -anyone can play accurately -- but I play with wonderful expression." As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte."The recording industry is creating a society of Ballard 11 listeners who expect performances to be technically perfect. This is because recordings are rarely untouched by the sound technician. There are fewer albums being released each year, relative to the number of albums released in total, that are "live." Much of this can be attributed to the listener's ear being more acclimated to music that is done accurately and cleanly. Students need to know that music-making is not a process for which the goal is perfection. Developing an atmosphere that fosters creativity follows well the idea of creativity being a "divergent, yet related, path." Effective factors of a creative learning environment focus on openness within parameters. Creative Instructional Strategies The lessons comprising the project that accompanies this essay (www.jgudgermusic.com) will be outlined in the next section, but I would like to first present the concepts central to the creative instructional strategies involved. The concepts central to each of the respective lessons can be adapted and combined in the planning of any music lesson. As previously noted, musical creativity is something that can be enhanced, and these are some of the qualities of instruction that allow that to happen. In order to form divergent ideas, individuals first need the ability to recognize how the “standard” system functions. From the accompanying project, the lesson "Notation," requires the student to have a basic comprehension of standard music notation before proceeding. Then they are encouraged to consider how our standard Ballard 12 system is only one possible way of describing music which exists independently of the written notation. While still using countable note lengths and twelve notes to the octave, the students are asked to discard the staff, clef, and rhythmic system, such as the quarter note or half note. They are now free to think about describing the music in a way that best makes sense to them. The “Notation” section of the project essentially teaches students how to recognize the norm and then deviate in a constructive manner. In other words, the notation is describing the music; and not the other way around. This shifts the focus from handling the notation, which is the most common perspective of music programs, to the music itself. The student in a band or strings class understands the basic components of music notation and has had regular practice at associating music with notation. As the student is familiar with the knowledge leading up to the point of departure, then left to answer how they will notate the music, they are traveling the "divergent, yet related, path." Students must be able to make their own decisions (Corporon, 1999, p. 86). Repetition of rules and simply rewriting good examples of desired outcomes allows little room for divergent ideas. Students must be provided with a set of tools, or “scaffolding,” and a general direction toward success. For instance, in the lesson, "Improvisation of Melodies," the participant is invited to play notes along with a background. Although the user begins the activity with access to only three notes, the user has complete freedom of how to use those pitches in relation to order of succession and rhythm. Ballard 13 Lessons that feel more like games are much more likely to be successful. People learn through experience, with playful experience being much more effective. Playful experience forms a positive association with the topic and content and is simply more likely to keep the student interested (Sullivan, 2005-2, p. 34). The lesson, "Creating Rhythms," focuses on conveying that composition is improvisation which is developed within certain guidelines with set variables and ultimately written down and improved upon. The lesson allows the student to experiment with various rhythm cells in playing them together with a steady tempo. It is very straight- forward and game-like, providing the students experience with rhythms and insight as to how they pick tools with which to compose. In this essay, we have defined the combination of two or more previously unrelated parts of an individual's experience or knowledge to be a creative act. In the lesson, "Music and Art," the goal is to help students form connections between two different mediums of art from the same art movement or period (Sullivan, 2006-1, p. 24). In the case of this lesson, they are comparing paintings with musical recordings. They are encouraged to look for common traits such as the subject of the work, use of color, or general mood presented. This begins to contextualize this knowledge for the students and provide them with insight as to how art of all sorts can describe a particular cultural atmosphere. We need to provide our students with goals outside of their comfort zones and a way with which to access them (Korn, 2009). It is extremely important to the creative process to regularly present concepts and art to students that move them outside of Ballard 14 their "comfort zone" (Sullivan, 2006-1, p. 24). In the lesson, "Describing Music," the students use a set of six criteria to describe three pieces of music from three widelyvarying genres. The purpose of choosing music that is unfamiliar to them is to move them out of their "comfort zone" through utilization of the tools, or the six criteria, that will make it accessible to them. I have intentionally chosen to include unfamiliar music for this age group as it is more likely they will be able to effectively examine their characteristics. When students take standardized tests that emphasize core subjects, such as reading, writing, and math, their goal is to find the one correct answer. It is vital that we make clear to students that beyond “standard concepts,” there is seldom--if ever--only one answer to any situation. This is especially true in the arts (Corporon 82) while contradicted by the assessments vital to a school's placement relative to NCLB. Lessons in the accompanying project, like the one on "Characterization," very clearly demonstrate the subjective nature of music to the students. Students learn the concept of characterizing a piece of music through a particular example that has been provided for them. The goal, though, is to encourage students to develop their own characterizations for motives within a solo work in the process of creating a story they can tell through performing their piece. The example given in the accompanying project includes two major motives and two minor motives. For each mode, there is a motive that may sound like an introduction and one that may sound like an affirmative statement. These particular motives were selected so that characterizing them would be relatively straight-forward, Ballard 15 but not restricting. At the end of the lesson, students are provided with a couple of ideas for other ways they might characterize the motives. From them, they may create a piece of music as a story. The creative instructional strategies highlighted by these lessons can be used in practically any lesson plan. Implementation of these techniques does not require extensive reworking of existing plans or revision of proposed lesson plans. Because they are more of perspectives than structures or activity-specific tools, they will not add significant instruction time onto lesson plans. This is especially useful in schools that are cutting instructional time for the arts to focus the students' efforts elsewhere. These strategies are useful lenses through which to approach instruction. Curriculum In 1994, the Music Educator's National Conference, along with its counterpart organizations in Dance, Theater, and the Visual Arts, devised the National Standards for Arts Education. In the publication of the Standards, art is defined as: (1) creative works and the process of producing them, and (2) the whole body of work in the art forms that make up the entire human intellectual and cultural heritage. We will focus most of our look at the Standards on the first definition, since we have discussed how creativity is developed in the process of producing a creative work. This provides an opportunity to help students develop as creative musicians. Each of the National Standards for Music Education for grades nine through twelve allows for an Ballard 16 approach focused on developing creativity that utilizes what we know about learners and how they learn. These lessons can be utilized by students from late middle school through high school. Students from any background will find these accessible as they do not rely on music specific terminology. They may be used in conjunction with classroom lessons or independently of school to strengthen creativity and explore various aspects of the arts. For instance, the lesson "Improvisation on Melodies," could be used as a personal introduction for high school jazz band students beginning work on improvisation as well as to provide a non-instrumental student the opportunity to create in a musical mode. This lesson could even be used by an art teacher to explain how the creation of art rarely begins with a blank slate, but with parameters or variables. The next step for the art teacher would be to demonstrate how it is easier to begin making creative decisions about creation by starting with a small palette. Each of these lessons are very adaptable and could be utilized in many settings focusing on either creativity, music, the arts, or creating. For each standard, I will provide one activity on my project website, www.JGudgerMusic.com, to demonstrate a creative approach for utilizing the standard. Content Standard #1: Singing, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music. Content Standard #2: Performing on instruments, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music. The explanations of both standards explicitly state that students should sing or perform, respectively, "with expression and technical accuracy a large and varied Ballard 17 repertoire." Music teachers are often very proficient at addressing technical accuracy, but it is very easy for an ensemble director ask their students to play with expression or with emotion without providing ideas or scaffolding to help them reach that goal. -----Example Activity on www.JGudgerMusic.com : Characterization of Motives 1. Present several clickable two measure motives that vary in mode between the major key and its relative minor. 2. Provide an example of characterization for each of the motives that are relevant to each other. 3. Have students listen to the motive while thinking of the assigned characterization. 4. Present the story in its complete form with clickable motives. Include the motives in altered formats. 5. Explain how a composer can modify a motive to reuse it throughout a piece. 6. Present the motives again and invite the student to characterize the motives. Ask the student to make a story with the motives and apply characterization to a piece of music he or she is working on. Content Standard 3: Improvising melodies, variations, and accompaniments Improvisation is relatively rare in strings, band, and choral classrooms, making its appearance almost exclusively in jazz ensembles However, improvisation can be utilized to a significant degree in any of those formats. It should be understood, though, Ballard 18 that improvisation within any particular style of music often will benefit from agreeing with the harmonies utilized in that music. One common approach is to start students improvising on a pentatonic scale simply because as long as they play one of the five notes in the scale, they can't be "wrong." -----Example Activity on JGudgerMusic.com : Simple Melodic Improvisation 1. Melody over an accompaniment - The student will be given the option of clicking on three notes (C-F-G) to see how they sound. 2. An accompaniment will play in the key of C, and the student will choose from the same three notes to play over the accompaniment. 3. Finally, additional notes from the key will be added that aren't as "safe" as the original three from which to improvise. 4. Tell the students that the three notes used are the 1st, 4th, and 5th scale degrees and that knowing how to find those in any key will allow them to play with practically any band at a basic level. Content Standard #4: Composing and arranging music within specified guidelines The composition and arrangement of music are often believed to require a great deal of prior work in subjects such as music theory or orchestration. Because of this, music programs may not address music composition or arranging with their students. To make them less intimidating, it can be effective to address the various attributes of Ballard 19 composition separately, before putting them back together. These include rhythm, pitch, articulation, dynamics, instrumentation, timbre, and many others. -----Example Activity on JGudgerMusic.com: Rhythm Creation 1. Introduce the student to a couple of rhythm cells and provide them with the corresponding sound representation. 2. Play rhythm cells at choice to a tempo. 3. Relate success in composition and improvisation to making a few initial decisions that narrow the choices for the composition. The rhythm cells are your tools. Content Standard #5: Reading and Notating Music Reading music is a common focus of most instrumental music programs. Sight reading is required in most auditions students encounter, ranging from auditions for honors bands to auditions for in-house jazz bands. There are many methods for teaching sight-reading of notation, but it is much less common for students to practice the reverse process of notating music that they first hear. Another problem associated with intense drill in reading music notation is the perception of the student that the music exists on the page. That would mean it appears unalterable and static. It is important that we explore alternative methods of notation and the idea that music notation is just a suggestion as to how music should be played. We can then help our students to understand how notation works and how it relates to music. -----Example Activity on JGudgerMusic.com: Alternative Notation Ballard 20 1. Play a musical example. 2. Present standard, recognizable notation for that example. 3. Offer an alternative example of notation representing the given musical example. 4. Provide a detailed explanation of the new example notation. 5. Invite the student to offer alternative rhythmic notation. 6. Invite the student to offer alternative pitch notation. 7. Relate standard notation to music and its relativity in general. Content Standard #6: Listening to, analyzing, and describing music In the classroom, I have observed that some students seem “numb” to the process of listening. They find it unfathomable that before recordings, people had to listen to actual musicians performing every time they wanted to hear music. On my first day with General Music classes at J. T. Moore Middle School, during my student teaching, students found it extremely uncomfortable that they would be allowed to sit and listen to music for one minute as a participation grade. Music to many people is something to which you drive, work out, or do work around the house. Many students have not yet discovered how to listen to music as a cognitively participatory activity. We must find ways to help them access music as experiencing new things is essential to the creative process. -----Example Activity on JGudgerMusic.com: Describing Music Ballard 21 1. Describe several characteristics of music for which students should identify by listening for them. 2. Provide the names of those characteristics to the students as they listen to a musical example of something unfamiliar. Ask them to consider those attributes in light of the unfamiliar music they just heard. 3. Provide sample responses for those attributes on that particular piece of music. 4. Play another piece of music; again, with those characteristics of music provided so they can keep them in mind. Invite them to write down their responses. 5. Play a very different piece of music, such as that from other countries, and have students write responses on the various characteristics of that music. 6. Ask them to compare their written responses. Content Standard #8: Understanding relationships between music, the other arts, and disciplines outside the arts. Content Standard #9: Understanding music in relation to history and culture. Contextualizing knowledge is one of the best ways to relay new information to students. Our brains naturally strive to relate knowledge, since that is how we make sense of the world around us. Studies of the arts or of history can enhance the learning experience by providing context for public school students. Ballard 22 For instance, if a class addresses the Great Depression, then lessons may be prefaced with a display of art leading up to 1929; or, with music-listening sessions to set the scene for the crash of the stock market. Conversely, a music teacher addressing jazz may talk about art that was associated with that form and era of music. These teaching methods will help students to understand that these arts do not exist on their own, but must be considered in light of cultural and societal influences. -----Example Activity on JGudgerMusic.com: Music and Art 1. Explain how parallels exist among various arts, in such aspects as: general mood; subject; the person experiencing it; and method of creation. 2. Provide a painting and a recording from the same cultural-artistic period and location. 3. Ask guiding questions that lead students to draw parallels between the painting and recording. 4. Relate the cultural-artistic period and location to historical events. 5. Provide a very different example from a different time period and setting as done in steps 2-4. 6. Invite students to think about their music, the artwork or posters that might go along with it, and the general mood or common subjects of their music. 7. Ask them what a painting of their favorite song would look like and provide guiding questions to help translate their favorite songs to a visual perspective. Ballard 23 Assessment Products are easy to assess, but processes are not. Therefore, we must focus on the variables that surround the process of creativity. The rubric below approaches the assessment of creativity in the classroom from this perspective (Categories adapted from Auh and Treffinger). Understanding of the Depth of Thought Standard or Example Process (in written Method explanation) Level of Motivation Understanding of the Uniqueness of Task's Fixed Product Variables I Demonstrates Clearly considerable effort demonstrates a firm in planning, understanding of the connecting ideas in Standard Method. an interesting way. Followed all Student exhibits a guidelines and high level of intrinsic functioned within motivation. the parameters of the task. II Has somewhat of an understanding of the Standard Method. Could use some review. Student exhibits Demonstrates some some intrinsic effort in planning, motivation or a but lacks quality or mixture of intrinsic organization. and extrinsic motivation. Followed most of the guidelines and functioned in the general direction of the goal of the task. Review of instructions. III Understands very little about the Standard Method. Requires work. Student exhibits Demonstrates some almost no thought, but no motivation, with planning at all. only motivation being extrinsic. IV Student is unfamiliar Fails to demonstrate Student does not with the Standard any thought toward seem interested in Method entirely. task and/or planning. the task at all. "Stretch" For the Student Product is significantly unlike any other presented in the class Product and thought process is significantly different from previous classroom experiences Product is significantly divergent, but not unlike other students' responses. Product and thought process incorporate new ideas, but not considerably different from prior classroom experiences Product demonstrates some Did not follow any of effort, but is the guidelines, but reproducible by worked toward the others or common goals. among student responses. Product and thought process included no new ideas, but effort was present. Product is very Did not follow any of common, the guidelines or demonstrates a lack work in the direction of effort, or is nonof the goals. existent. Product was nothing new to the student's prior classroom experiences or nonexistent. The first category, "Understanding of the Standard Method," is an assessment of the student's understanding of the foundation from which they will be diverging. How can students be creative if they don't understand what is "normal" or what would not be Ballard 24 known as creative? Or, what is a rebel if she doesn't understand what it is she's "rebelling from?" Students must understand the framework and processes they are leaving behind, or upon which they strive to improve. They must also understand why the Standard Method for doing something is the Standard Method. What is good about it, and what needs their improvement? There must be a reason, for instance, why Western music uses the five-line staff with quarter notes and half notes. Students would benefit from understanding this before attempting to alter it. Their divergent ideas will be much more informed and well-founded if they first understand the standard method. The second category, "Depth of Thought Process," is perhaps the most vital aspect of the student's work, since creativity is exclusive to the process; not the product. The product is simply the result of the creative process. If a student is to be assessed on creativity, then his thought process is the most important part. He could be asked to write a few sentences of self-analysis describing how they started with the standard method or given an example and then found their way to the resulting product. It is also vital to note that their consciousness of this process is the key to developing their creativity. To them and to the teacher, there is no longer a value judgment of, "Either they're either creative or they're not." Creativity is now becoming tangible to both. The third category, "Level of Motivation," addresses the fuel students have with which to engage the creative process. They may be very creative, but without motivation, they will not be able to put substantial effort toward the creative process. Some students may have a great deal of motivation, but lack the guidance to utilize it. It Ballard 25 is absolutely imperative that both the student and teacher know if the student's creativity is being hampered by their knowledge, ability, and organization, or by their motivation. A distinction must also be made between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Whereas extrinsic motivation may compel a student to engage in the process of creating a product, extrinsic motivation is concerned with the product and not the process. Students need to be able to work in an atmosphere that rewards the well thought-out process fueled by their own intrinsic motivation over the product. We need to know why our students are creating. The fourth category, "The Understanding of The Task's Fixed Variables," must receive close attention, because, as discussed earlier in the essay, it is much easier to paint, for example, after making a few initial decisions about the work and how it is to be created. A blank canvas in an empty room can be terrifying. What kind of paint will you use? What size canvas would be best? What is your subject? What mood will you set? Within the atmosphere set by those five questions alone, there is still a dauntingly vast realm of possibilities for divergence. If students are not able to focus their divergent efforts in a certain direction, their attempts to create will be much more difficult. With the open atmosphere set by effective creatively-based lessons, deviation from the set parameters of the task can result in an entirely new assignment. Following the guidelines of the assignment insures the student will work in the intended direction while maintaining an opportunity for divergent thought. The fifth category, "Uniqueness of Product," should never be the goal of the task, but it does provide evidence to the uniqueness of the creative process utilized. If the student engages himself or herself in a unique creative process, then it is very likely that Ballard 26 the product will be unique. This idea is very different from how products are most commonly assessed since most programs have an ideal, or correct, way for a passage of music to be performed. The extrinsic motivation provided by displaying or praising interesting and unique products is often needed to get students interested initially. From there, a shift of their effort from the product to the process will inevitably result in a unique product. The final category, "Stretch for the Student," is very important, because some students may enter the classroom at the beginning of the semester with a more developed consciousness of the creative process than others attain even at the end of the semester. When assessing growth in the arts, in general, students will often receive the most benefit from self-comparison and reflection. This category allows the teacher to consider how much relative effort it took the students to reach outside of their "comfort zones" while completing the task. For some students, displaying a little bit of creativity may be monumental whereas other students, who are already very creative, may have to produce a seriously planned and executed work of art in order to show progress. This category makes the assessment unique to the student and allows them to grow considerably. Even though I have developed a rubric with the goal of assessing creativity, it is most important that effort be the most vital aspect of any student's evaluation. The goal of the six categories is to provide insight as to where the students must focus their efforts on future tasks. Any student is capable of succeeding by these criteria as long as they sincerely try. Ballard 27 Impact on My Practice Very few secondary school music students will pursue a career in music. Some of them will continue to perform in local settings for the experience, and maybe a few of them will go to college for music. We must make sure each one has gained something he or she can carry with them beyond the walls of the band room. We, as music educators, can address many subjects within our rehearsal periods or general music classes, such as history or math, but this atmosphere, coupled with the idea of creativity as bringing together previously unrelated ideas, is an opportunity that should not be passed up. My goal in teaching music is to help students develop their ability to learn; attain knowledge through methods they develop or improve; and look for opportunities to understand an idea or concept, then take it in a new direction. During student teaching, I have consciously welcomed and built upon student input, helped guide students’ thinking as opposed to giving them the answers, addressed how certain difficult academic situations might be approached, and provided opportunities for students to extrapolate the evolutionary turns of musical development, both in the past and in the future. I constantly fight the urge to sing a line of music to an ensemble or to tell them exactly how I would like a phrase of music to be performed. Rather, I invite their interpretation by providing technical assistance, while asking them about the line and reminding them of what variables they need to address. When their interpretation is matched with good listening skills, the ensemble will play a piece uniquely and in a unified manner. The truth is, though, that after discussing history surrounding the composer and compositional technique, the students usually Ballard 28 come close to what I would envision beforehand. If they are completely in another realm from the style of music they are performing, they can always be challenged with higher order, “Bloom’s” questions that stimulate their thinking and draw upon the preparatory knowledge surrounding any piece of music. In general music classes, I will be sure to include open-ended questions in class questioning and on quizzes, tests, or other written assignments. I enjoy discovering what experiences students will bring to class. It also helps personalize the students’ experience in class to have their unique input invited by the teacher into the curriculum. When the goal is a correct answer, the student is allowed to stop thinking about the question after answering. When the goal is a process, there is always opportunity to readdress the question and further develop their ideas. Open-ended questioning is key to developing creativity. My students will be invited into the decision-making process in an environment in which they will have freedom within fixed variables. There will be some right or wrong answers for concrete facts, but when addressing music, they will be guided and allowed to take tangential paths. My goal is to shift their thinking from the product to the process. Ballard 29 Works Cited Abril, Carlos R (2006). The State of Music in the Elementary School: The Principal’s Perspective, Journal of Research in Music Education, 54:1 (Spring), p. 6-20. Adolphe, Bruce (1991). The Mind's Ear. St. Louis: MMB Music. Auh, Myung-sook (2000). Assessing Creativity in Composing Music: Product-ProcessPerson-Environment Approaches. Sydney: Centre for Research and Education in the Arts, University of Technology. Baer, John (1993). Creativity and Divergent Thinking. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Blocher, Larry R (1997). "The Assessment of Student Learning in Band." Teaching Music Through Performance in Band, v. 1, p 27-30. Blocher, Larry R (2000). "Making Connections." Teaching Music Through Performance in Band, v. 3, p. 4-13. Center For Education Development in Fine Arts. Motivation. http://finearts.esc20.net/music/music_strategies/mus_strat_moti.html Corporon, Eugene M (1999). "Fervor, Focus, Flow, and Feeling: Making an Emotional Connection." Teaching Music Through Performance in Band, v. 3, p. 81-86. Daignault, L (1997). Children’s creative musical thinking within the context of a computer-supported improvisational approach to composition. Dissertation Abstracts International, 57, 4681A. Hickey, Maud (2001). An Application of Amabile's Consensual Assessment Technique for Rating the Creativity of Children's Musical Compositions. Journal of Research in Music Education, 49:3 (Fall) p. 234-244. Hodges, Donald A (2000). Special Focus: Music and the Brain: Implications of Music and Brain Research. Music Educator’s Journal, 87:2 (September) p. 17-22. Koestner, R., R. M. Ryan, F. Bernieri, and K. Holt (1984). Setting limits on children's behavior: The differential effects of controlling versus informational styles on intrinsic motivation and creativity. Journal of Personality, 39. Korn, Mitchell (2009). Personal notes taken from a lecture given on 2-9-2009 at West End Middle School. Nashville, TN. Ballard 30 Lisk, Edward S (2002). "Beyond the Page: The Natural Laws of Musical Expression." Teaching Music Through Performance in Band, v. 4, p. 29-43. Lisk, Edward S (2009). "Imagination and Creativity: A Prelude to Musical Expression." Teaching Music Through Performance in Band, v. 7, p. 17-24. Priest, Thomas (2001). Using Creativity Assessment Experience to Nurture and Predict Compositional Creativity. Journal of Research in Music Education, 49:3 (Fall) p. 245257. Reimer, Bennett (1997). Music Education in the 21st Century. Music Educator’s Journal, v. 84 (November) p. 33-38. Sullivan, Timothy (2005-1). Principal Themes: Creativity and Music Education - First of a Four Part Series. Canadian Music Educator, 47:1 (Fall) p. 24-27. Sullivan, Timothy (2005-2). Principal Themes: Creativity and Music Education Second of a Four Part Series. Canadian Music Educator, 47:2 (Winter) p. 33-37. Sullivan, Timothy (2006-1). Principal Themes: Creativity and Music Education - Third of a Four Part Series. Canadian Music Educator, 47:3 (Spring) p. 23-28. Sullivan, Timothy (2006-2). Principal Themes: Creativity and Music Education - Fourth of a Four Part Series. Canadian Music Educator, 47:4 (Summer) p. 23-27, 60. Treffinger, Donald J., Grover C. Young, Edwin C. Selby, and Cindy Shepardson (2002). Assessing Creativity: A Guide for Educators. Research Monograph Series. Storrs: University of Connecticut, The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented. Wilde, Oscar. The Importance of Being Ernest.