Capstone- 2010- Clark

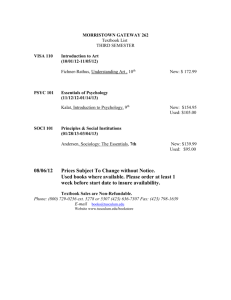

advertisement