Revised Thesis 1

advertisement

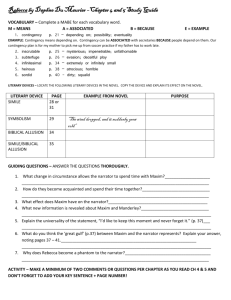

1 Running Head: DO PRESCHOOLERS USE CONTEXT CUES Do context cues help preschoolers learn words by differentiating between reliable and unreliable informants? Michelle Doscas Vanderbilt University 2 Abstract The present study investigates if 4-year-old children use people’s pragmatic competence as a standard for learning from them. In this study we define a person’s pragmatic competence by their ability to adhere to the Gricean maxim of relation. The children were divided into three conditions with different levels of verbal context, a no context condition, a rich context condition and a richer context condition. Four-year-olds did not perform differently based on the level of context they received. A linear regression revealed that children’s ability to answer comprehension questions correctly while watching a video, predicted their performance on the word-learning task. 3 Do context cues help preschoolers learn words by differentiating between reliable and unreliable informants? Children can learn quite a bit from engaging in conversations with others. For example, they can learn to wait their turn and to ask relevant questions, as well as learn about various things around them. However, children need to have a certain mastery of pragmatic competence to understand and follow conversations. They need to know when it is their turn to speak, when to answer questions relevantly, and many other things. When speaking to a young child, one can tell when they do not fully understand some of these pragmatic steps. For instance, when talking to a four year old, you may ask them, “What’s your name?” and they may reply with an answer that is not only not their name, but instead is a very long story about something that happened to them on the playground today. Below I review research that investigates when preschoolers might understand principles of conversation. In 1975, Paul Grice identified and defined several conversational maxims that are necessary to understand speech. These maxims are known as Gricean maxims. The four main Gricean maxims are quality, relation, quantity, and manner (Grice, 1975). Quality is the idea that one must say what they know to be true in a conversation. Relation is that one must make their statement relevant to the conversation. Quantity refers to the idea that one should only say as much as is needed. Manner means that one should avoid ambiguity and be clear. One assumption is that speakers have to adhere to these principles for conversation to proceed smoothly. As long as speakers adhere to a principle to be cooperative during conversations they can violate the maxim to convey non-literal meaning (like sarcasm). But they may also violate the maxims if they are distracted or unable to (because they do not understand them). One question is when children understand why maxims are violated. 4 Previous research shows that children between the ages of three and five understood when the quality and relation maxims were violated (Eskritt, Whalen & Lee, 2008). In this study, three to five year olds performed a task that involved finding a sticker hidden underneath one of four possible cups. Children were shown two puppets, one of which was a Gricean maxim adherer and the other was a non-adherer. The children were told that they could ask one of these puppets for help finding the sticker during the test trials, but were not told that one would be more helpful in finding the sticker than the other. For example, in a condition investigating children’s understanding of the relation maxim, the puppet that was the Gricean maxim adherer would say, “It is under the blue cup” when asked where the sticker was, but the puppet that was the Gricean maxim non-adherer would respond by saying, “I like these cups.” That is, the puppet that was the Gricean maxim non-adherer would provide irrelevant information that did not answer the question properly. Children were told that they could ask one of two puppets for help finding this sticker, and they were allowed to keep the sticker if they found it on the first try. There were four practice trials followed by ten test trials. The only difference between the practice trials and the test trials was in the practice trials, the experimenter (rather than the child) picked the puppet. In two of the practice trials the experimenter picked the puppet who adhered to the Gricean maxim (so the child was able to find the sticker), and in the other two practice trials the experimenter picked the puppet who did not adhere to the Gricean maxim (so the child was not able to find the sticker). During the ten test trials, the child was asked to pick a puppet each trial in order to find the sticker hidden underneath one of the four cups. This study found that 3-5-year-old children picked the puppet that adhered to the maxim. They were most likely to do this when the puppet violated the quality maxim (be truthful) and the relation maxim (be relevant). 5 In a more recent study, researchers used a different method to investigate whether 4- and 6-year-old children understand violations of the relation and quality Gricean maxims (Vazquez, Delisle, Saylor, under review) and whether they will use the information to decide who is more likely to know the names for things. Previous research has shown that children are more likely to trust a speaker who was previously reliable, and they will in turn endorse this speaker when learning words for novel objects (Koenig & Harris, 2005, Pasquini, Corriveau, Koenig & Harris, 2007, Birch, Vauthier & Bloom, 2008). During the Vazquez et al (under review) study children watched an interaction between two people, and then watched a second interaction between two people. During the interactions one person asked another person questions. In one of these interactions the person being questioned answered a question in a way that showed adherence to a Gricean maxim (‘good’ social partner), and in the other interaction the person violated the maxim (‘bad’ social partner). If children recognize that one person adhered to the maxim and one person violated the maxim, they should be able to pick the person who was better at answering questions. After the participants watched two videos in which an actor violated the maxim, they were asked which person would be more likely to know a name for something. Each maxim was tested in separate conditions. This study has found that six year olds identified adherence to both the quality and relation maxims and chose person who adhered to the maxim as the good labeler. They found that four year olds identified the maxim non-adherer (bad social partner) in the quality condition, but not in the relation condition. They also found that four year olds picked the maxim adherer (good social partner) as the good labeler for the quality maxim but not for the relation maxim (Vasquez, Delisle & Saylor, under review). There is a discrepancy between these two studies. Recall that, Eskritt et al (2008) found that even three-year-olds could identify violations of the relation maxim (be relevant). In 6 contrast, Vazquez et al (under review) found that four year olds were unable to identify the nonadherer in the relation condition. What might account for this difference? One reason that this may be is that in the Eskritt et al (2008) study, children were provided with a large amount of feedback during a training period as well as incentives. Their study had a training period, where the children learned the procedure before they had to participate in the experimental portion. Also, the children received stickers for every question that they answered correctly on the first try, which may have provided an incentive for them. In the Vazquez et al study, the children were not put through a training period, and were not provided with any feedback or incentives. One possibility is that four year olds actually may need more support to identify violations of the relation maxim. One reason is that violations of the relation maxim are not as clear-cut as violations of the quality maxim. For example, in the Vazquez et al (under review) study, the non-adherer to the quality maxim is asked, “How many balls do you have there?” and they respond with, “I have sixty balls here!” they are then asked, “Where is the green ball?” and they respond with, “On the floor.” In this case, the quality non-adherer is simply not responding truthfully to the questions being asked. The non-adherer to the relation maxim is asked, “How many balloons do you have there?” and they respond with, “I like to eat turkey!” and then they are asked, “Where is the red balloon?” and they respond with, “See my nose.” In this study, the relation non-adherer responds with completely irrelevant information, causing the child to have to think about and remember more themes. Another reason why the quality maxim may be a little simpler for the children to understand is because they can see and also hear that the person is not being truthful, and therefore violating this maxim. For example, the child is able to see on the video that the person is only holding two balloons, and therefore when she says that she has sixty, she is clearly 7 lying. Because children have a harder time recognizing the relation maxim, they may need more help with understand this concept. In my study I investigated four year olds ability to recognize the difference between people who adhered and did not adhere to the relation Gricean maxim. Without any help out at all, four year olds consistently fail tasks in which they are asked to recognize a non-adherer of the relation maxim. I gave four year olds different levels of verbal scaffolding using the Vazquez et al. procedure to attempt to help them identify when the relation maxim is violated. In the first condition, the no context condition, the children received no verbal scaffolding. This condition acted as a baseline measure of children’s ability to identify the maxim non-adherer. In a second condition, the rich context condition, the children were told that the girls in the videos would try their best to answer the questions correctly. In the third condition, the richer context condition, the children were told that the girls in the video would try their hardest to give the right answer to the questions and were also given evidence of a person offering good answers to questions. I hypothesized that the four year olds would fail to identify the relation maxim nonadherer (bad social partner) as well as not choose the adherer to the relation maxim (good social partner) in the word-learning test in the no context condition, like they have in the past with similar procedures, and that the four year olds would perform better (be able to recognize the adherer from the non-adherer and subsequently choose the adherer as giving good labels) in the rich context and richer context conditions because of the extra verbal scaffolding help. Methods Participants 8 Forty-Eight 4-year-old children participated in this research (M=53.92 in months). All children were English speaking and typically developing. Children were recruited from a database of interested participants. Five additional children participated but their data were excluded because of non-compliance (2), counterbalancing error (1) and experimenter error (2). Materials Two 13-inch television sets were placed in a table in front of a couch, and were connected to DVD players. The experimenter controlled the DVD players with corresponding remote controls. A digital camera was used to record the session. The participants were shown two short video clips that lasted about thirty seconds. The video clips included one of a good social partner and the other of a bad social partner. The social partners are both females, and interacted with the same male actor in each video. One of the social partners played with balloons, and the other played with balls. The good social partner reliably followed the relation conversational maxim, while the bad social partner did not follow this convention. The bad social partner replied to questions with irrelevant answers. A box was used to house the 8 novel objects used during the word labeling trials. The novel objects were purchased at a crafts store or made by removing parts from larger objects until an unrecognizable part was left and they would be unnamable by children. Novel objects were paired based on similar features, but were not identifiable (e.g. size, material). Each pair was associated with one of four novel labels (i.e. dake, teg, glap, trome). See Figure 1. Design and Procedure Children were randomly divided into three conditions with the constraints that there be equal numbers of boys and girls in each condition and that the mean age across conditions would be equal: no context (M=54.42 in months, SD=3.29), rich context (M=53.95, SD=3.94), and 9 richer context (M=53.38, SD=3.28). In the no context condition, children were not given any information about what they were going to see. In the rich context condition, children were shown a picture of the three actors in the videos and given a short explanation about their intention in answering questions. In the richer context condition, children were shown the same picture, but then were given a longer explanation of the intentions of the actors as well as asked a few leading questions to help them think in a certain way. Both context conditions are described in greater detail below. The children were tested on the relation maxim in the no context condition and in either of the two experimental conditions. Each condition included two phases, the familiarization phase and the word-learning phase. I begin by describing the procedure for the no context condition. Participants sat in the middle of the couch equidistant from the television sets. When no video was playing, each television displayed an image of the actor whose video would be shown. The experimenter always sat to the right of the participants. The box of novel objects was placed out of view from the child, next to the experimenter. They were told that they would be watching videos. No Context Condition. In this condition there was a familiarization phase and a wordlearning phase. There was no additional information provided to the child before they watched the videos. In the familiarization phase, the children were shown both of the videos and were asked to determine the good and the bad social partner. In this phase we are looking to see if they can identify the reliability of the actors based on the relation conversational maxim. The experimenter first introduced the actors by saying, “We are going to watch some of my friends on TV. One of them is wearing a pink shirt, and the other one is wearing a red shirt. Can you point to the girl with the pink shirt? Can you point to the with the red shirt?” The children then watched the first video, and were asked two comprehension questions after it was 10 over. For example, the child was asked, “When he asked her how many balls she had what did she say? When he asked her where the green ball was, what did she say?” After this, the child watched the same video again, and was then asked, “was she good at answering questions, or was she not very good at answering questions?” This procedure was then repeated for the second video. After the second video and questions were completed, the child was asked, “Who was better at answering questions?” After this question was asked, the word-learning phase began. The experimenter introduced this idea by saying, “They were both here yesterday, and I asked them some questions about the toys in this box. I asked them the names of the toys, but I don’t know the names of the toys, so you’ll have to help me figure it out.” The word-learning phase looked at the child’s ability to learn new words or labels from each social partner. It consisted of four trials, and in each trial the child was presented with a pair of novel objects labeled by each of the actors. The children had to decide which object was labeled correctly. One of four novel labels (i.e. trome, dake, glap, teg) was presented in each trial and participants determined the correct referent. All of the novel pairs were presented in the same way. The experimenter showed the object to the child and placed it in front of the picture (on the TV screen) of the corresponding actor, while saying, “The girl in the red shirt said that this was a trome.” The experimenter then says, “And the girl in the pink shirt said that this was a trome.” The experimenter then looks at the child and says, “They can’t both be tromes! Only one can be a trome. Which one is the trome?” The participant then selected an object by pointing or describing it. All factors in this experiment are counterbalanced. The actor who played the good social partner, the television on which the good social partner’s video was shown, and the order in which the videos were shown were all counterbalanced. The order of the questions asked were 11 counterbalanced, as well as the objects being labeled. Rich Context Condition. The rich context condition was the same as the no context condition except that, before the child was shown the videos during the familiarization phase, he or she was shown a small poster with three pictures on it. There was a picture of each actor in the videos. Screen shots of the girl with the red shirt and the girl with the pink shirt were at the top of the poster. There was a picture of Mark, the only male actor, underneath the girls’ pictures. The experimenter then said, “These are my friends, one is wearing a pink shirt and the other is wearing a red shirt. This is Mark, he likes to ask a lot of questions. Mark is going to ask my friends for help answering these questions, and they are going to try as best as they can to answer these questions.” After this the procedure continued as in the no-context condition. Richer Context Condition. The richer context condition was the same as the no context condition except that, before the child is shown the videos, they are shown the same poster as they are shown in the rich context condition. They are then told, “These are my friends, one of them is wearing a pink shirt and one of them is wearing a red shirt. This is Mark. Mark needs to answer some questions and he needs the right answers. He's going to ask my friends for help. They want to give him the right answer. For example, if he asks them what color the ceiling is, they should say that it is white. If Mark asked them what color the couch is, what should they say? (The child answers blue) That's right! They want to give him the right answer or (the child does not answer blue) now, remember they want to give him the right answer. What color would they say the couch is? Let's watch them! Remember, they want to give Mark the right answers.” The procedure then continued as in the no -context condition. Coding. 12 Comprehension questions. The comprehension questions were the four questions that the participant answered after watching each video clip for the first time. They received a score of 1 for a correct answer and 0 for an incorrect answer. The questions were open ended (rather than forced choice) and some children did not provide answers to one or more of them (e.g. saying “I don’t know,” or remaining quiet). These responses were not included in the analyses because we wanted to be sure that we did not underestimate children’s ability to follow the procedure. Since the total number of coded responses differed by child, the scores were converted to proportions (total number correct/number of answers provided). Conversation partner assessment and comparison questions. The children were asked three assessment questions while watching the videos. They were asked, “Was she good at answering questions or was she not very good at answering questions?” after watching each video. They were then asked, “Who was better at answering questions, the girl in the pink shirt or the girl in the red shirt?” They were given one point for each of these questions that they answered correctly. There was a possibility of them receiving a total of three points. Word-learning trials. In the word learning phase, the children were asked to choose the object that they believed was labeled correctly. There were four trials, and they were given one point for each of the objects that they chose that were labeled by the good social partner. There was a total of four possible points for this portion. We predicted that those children who correctly identified the good social partner in the assessment questions, would then be able to recognize that the objects labeled by the good social partner were the correctly labeled objects. Results In what follows, we first asked how well children understood the procedure by reporting their responses to comprehension questions. Then, we analyzed the conversation partner 13 assessment and comparison questions, which tested children’s ability to recognize adherence to the conversation maxim. After this, we looked at how children’s use of past pragmatic competence affected their ability to make inferences about the speaker’s reliability in the wordlearning phase. Finally, we asked whether children’s answers to comprehension questions or conversation partner assessment and comparison questions predicted their ability to choose the reliable speaker’s object in the word-learning phase. Comprehension Questions The children watched two videos in the familiarization phase, and after watching each of these videos for the first time they were asked two comprehension questions. These questions were put in place to ensure that the participants were paying attention to the videos. The effect of the comprehension questions was assessed with a 2 (sex) x 3 (condition: no context, rich context and richer context) ANOVA. There was no main effect of condition (F (2,48) = 1.30, p = .28). There was no difference in response ability across the no context (M = .75, SD = .29), rich context (M = .75, SD = .27) or richer context (M = .60, SD = .30) conditions. There was also no main effect of sex (F (1,48) = .00, p = .99). Males (M = .71, SD = .27) were not more likely to answer the comprehension questions correctly than females (M = .70, SD = .32). There was also not a significant sex by condition interaction (F(2, 48)=.94, p= .40). See Figure 2. Conversation partner assessment and comparison questions One goal of this study was to assess if children are aware of those who adhere to conversation maxims (specifically the relation maxim) by watching everyday conversations. We examined this from the two conversation partner assessment questions and the one conversation partner comparison question. The effect of verbal context on maxim recognition was assessed with a 2 x 3 ANOVA, with sex and condition (no context, rich context, and richer context). 14 First, there was no main effect of condition (F (2,48) = .66, p = .52). There were no differences in children’s ability to identify the maxim adherer across the no context (M = 2.32, SD = .749), rich context (M = 2.37, SD = .68), and richer context (M = 2.06, SD = .93) conditions. There was also no main effect of sex (F (1,48) = .55, p = .46). Males (M = 2.20, SD = .81) were not more likely to understand these questions than females (M = 2.33, SD = .76). There was also not a significant sex by condition interaction (F(2, 48)=.47, p=.63). See Figure 3. As another way to investigate children’s responding we asked how they performed on each question individually. The pattern of responses across condition indicated that children consistently answered the bad social partner assessment question incorrectly. In the no context condition, they answered the good social partner question (18 out of 19, p .05, binomial probability) and the partner comparison question (16 out of 19, p .05) correctly, but not the bad social partner question (10 out of 19, p =ns). In the rich context condition, they answered the good social partner question (18 out of 19, p .05) and the partner comparison question (17 out of 19, p .05) correctly, but not the bad social partner question (10 out of 19, p = ns). In the richer context condition, they answered the good social partner question (16 out of 16, p .05) correctly, but not the partner comparison question (10 out of 16, p=ns) or the bad social partner question (7 out of 16, p = ns). Word-learning test The word-learning phase assessed children’s trust of the conversation partners in the videos. We predicted that children would select the object labeled by the good conversation partner. We measured this with a 2 x 3 ANOVA, and word learning test score was the dependent variable, while condition and sex were the independent variables. There was no main effect of condition (F(2, 48) = .79, p = .46). There was also no main effect of sex (F(1, 48) = 1.10, p = 15 .30), or a significant sex by condition interaction (F(2, 48) = .12, p = .90). The scores for the word-learning phase were also tested against chance to evaluate the reliability of children’s responding. Four year olds were at chance in all three conditions; no context (M=2.21 out of 4, SD=1.03, t(18) =.89, p=.39) , rich context (M=2.47, SD=1.07, t(18)=1.92, p=.07) and richer context (M=2.06, SD=1.12, t(15)=.22, p=.83). See Figure 4. We used a linear regression model to investigate whether it was children’s attention to the videos (as shown by the comprehension questions) or children’s ability to identify the person who adhered to the maxim (as shown by the assessment questions) that predicted their performance. Comprehension score and assessment question score were the independent variables, and score on the word-learning test was the dependent variable. The model was significant (F(2, 51)=4.71, p=.01) with comprehension question score as the only independent predictor of children’s word learning scores (t(2)=2.69, p=.01). This suggests that children’s attentiveness to the videos was the only predictor of their ability to choose the correct referent during word-learning trials. See table 1 for raw correlations and the regression table. Discussion This study investigated whether adding verbal context would help four-year-olds better understand the Gricean maxim of relation. The verbal context did not seem to improve children’s performance over what was seen in previous research. While children showed an overall tendency to answer the maxim assessment questions correctly, they were not able to recognize the maxim non-adherer across any of the study conditions. Also, four-year-olds did not show a significant tendency to pick the good labeler in the word-learning phase. However, the children’s ability to answer the comprehension questions correctly while watching the videos were then able to pick the good labeler in the word-learning test. These findings show that four- 16 year-old children may struggle in recognizing the relation Gricean maxim, but may be able to pick the good labeler during the word-learning test if they pay close attention to the events in the videos. What have we learned about children’s knowledge about Gricean maxims? This research agrees with previous findings that four-year-olds struggle to understand the relation Gricean maxim. In one previous study, four-year-olds were not able to recognize relation maxim non-adherers, and were also not able to pick the maxim adherer as the good labeler for word-learning trials (Vazquez, et al., under review). This contrasted with a different previous study that showed that four-year-olds can recognize non-adherence to the relation Gricean maxim as long as they have an abundance of practice as well as incentives (Eskritt et al., 2008). While, four-year-olds were able to detect who the relation maxim adherer was they did not use this information to learn from the maxim adherer, and could not identify the person who violated the maxim. This last finding is the same as what the Vazquez et al (under review) study found. Four-year-olds were significantly more likely to recognize the good labeler if they answered the comprehension questions correctly. This suggests that four-year-olds are able to learn from the maxim adherer, if they are able to first be attentive to a conversation that they watch the maxim adherer have. What accounts for four-year-olds’ difficulty with the maxim of relation? Four-year-olds did not choose the novel objects labeled by the maxim adherer. When looking at their responses to the individual assessment questions, it is clear that the four-yearolds had a lot more trouble recognizing the maxim non-adherer or the ‘bad social partner.’ One reason why children may have struggled in this area is because the relation maxim violations may be somewhat harder for them to detect. The relation maxim can only be judged in the 17 context of a conversation, and therefore the violation might be harder to detect for four-yearolds. This detection may be difficult because the violations can often make sense out of context. For example, in this study, the maxim non-adherer gives the response, “I like to eat turkey,” and this could easily be a response to a question, but not the question that was asked (“How many balloons do you have there?”). The additional verbal context added in this study was an attempt to help them understand the speakers’ intentions. I hypothesized that helping the children understand that the speakers’ were trying as hard as they could to give the right answers would have helped them recognize the maxim non-adherer. The additional context did not help four-year-olds with recognizing the maxim non-adherer or with choosing the good labeler in the word-learning trial. The children may not have been able to comprehend and then hold the information given to them about the speakers’ intentions throughout the video clips. Also, knowing the intention of the speaker might not be as important as just paying attention to the conversation that is happening, because this study showed that four-year-olds who understood what was happening in the given conversation were able to learn from the relation maxim adherer. Our surprising finding was that four-year-olds in the richer context condition performed worse on the assessment questions than those in the no context and rich context conditions. In general, this condition seemed to confuse the preschoolers. The addition of extra context as well as asking them a question before the start of the test trial may have caused them to not understand what they were supposed to be paying attention to, but it may have helped others to focus on the people in the videos more closely. They were not able to consistently recognize the maxim non-adherer and they were not able to recognize which person was better at answering 18 questions. The relation maxim is difficult for them to understand in general, and adding too much context seemed to confuse them further. Summary. This study asked whether four-year-olds were able to recognize adherers and nonadherers of the relation Gricean maxim. They were provided with verbal context to help them understand the speakers’ intentions. This extra verbal context was expected to help the children recognize the non-adherer as well as help them choose the maxim adherer for the good labeler in the word-learning test. We found that four-year-olds did not perform differently in the study based on which level of context they were given. A linear regression showed that children who answered comprehension questions correctly throughout the video portion of the study, were more likely to select and learn from the maxim adherer during the word-learning test. Our findings suggest that four-year-olds continue to struggle to recognize the Gricean maxim nonadherer, and that presenting them with verbal context did not help them. Our results also show that children who focus and understand the conversation are able to better recognize the maxim adherer as the good labeler in the word-learning trial, and therefore this aspect of the study might be more important than previously thought. 19 References Birch, S.A.J., Vauthier, S.A. & Bloom, P. (2008). Three and four year olds spontaneously use others’ past performance to guide their learning. Cognition, 107, 1018-1034. Corriveau, K.H., Meints, K. & Harris, P.L. (2009). Early tracking of informant accuracy and inaccuracy. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27, 331-342. Eskritt, M., Whalen, J. & Lee, K. (2008). Preschoolers can recognize violations of the Gricean Maxims. The British Psychological Society, 26, 435-443. Grice, P. (1975). Logic and conversation. Syntax and semantics 3: Speech arts, 41-58. Koenig, M.A. & Harris, P.L. (2005). The role of social cognition in early trust. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 457-459. Pasquini, E.S., Corriveau, K.H., Koenig, M. & Harris, P.L. (2007). Preschoolers monitor the relative accuracy of informants. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 12161226. Sabbagh, M.A. & Baldwin, D.A. (2001). Learning words from knowledgeable versus ignorant speakers: links between preschoolers’ theory of mind and semantic development. Child Development, 72(4), 1054-1070. Scofield, J. & Behrand, D.A. (2008). Learning words from reliable and unreliable speakers. Cognitive Development, 23, 278-290. Vazquez, M.D., Delisle, S. & Saylor, M. (2009). Children’s and adults’ use of conversational cues when selecting sources of information. Under Review. 20 Table 1 Raw Correlations and Regression Analysis of Word Learning Test Score Word learning Variables (DV) Comprehension .40** Assessment .19 Comprehension B SE B β ___ ___ 1.46 .54 0.40 .48** ___ -.003 .20 -.002 Note: R squared=.16, Adjusted R squared=1.2, R=.40 **p<.01 Assessment 21 Figure 1. Test object pairs 22 Figure 2. Comprehension question scores 23 Figure 3. Assessment question scores 24 Figure 4. Word-learning test score