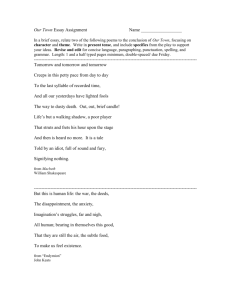

LovettCapstone

advertisement