FINAL REPORT- Lewis, Pearson, Hill

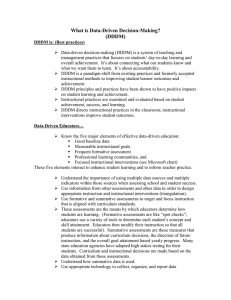

advertisement