Capstone Essay - Teaching with Graphic Novels by Charles Hershon

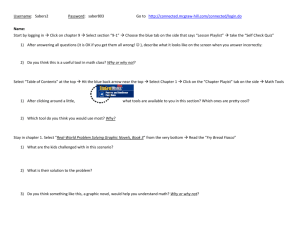

advertisement