PaguibitanCapstone

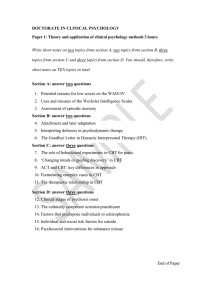

advertisement

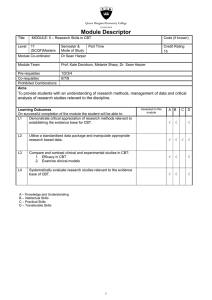

CBT Programs in Education 1 Running head: CBT PROGRAMS IN EDUCATIONAL SETTINGS TO MENTAL WELLNESS Promoting Mental Wellness in Education with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Interventions Gaudencio Powell Paguibitan Peabody College- Vanderbilt University CBT Programs in Education 2 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to argue for the implementation of an education program that is effective at preventing mental disorders and promoting mental wellness. This interdisciplinary paper between the fields of education and clinical psychology expands upon the use of effective cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) components in educational settings. National statistics on mental disorders in American adolescents are first discussed in order to raise awareness for the severity of the mental disorder epidemic in America. This paper will then address the misperception of mental health and call for a paradigm shift to mental wellness in order to remove the deficit mindset of mental health in education. A comprehensive literature review focusing on the use of CBT within adolescents diagnosed with depression and anxiety will be examined. Next, the best practices of standardized CBT manuals like the Coping Cat, Penn Prevention Program (PPP), Adolescent Coping with Depression course (CWD-A), Treatment For Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS), and Taking ACTION will be reviewed. Substantial data driven evidence for curricular suggestions were found within the categories of CBT goals, assessments, homework assignments, teacher student relationships, classroom environments, and flexibility. These components are suggestions to be used in future manuals promoting CBT in school settings. Each suggestion detailed is proposed within the framework of mental wellness in education for a population without with mental diagnoses. Finally, future implications for the field of clinical psychology and education are made with a proposal of a new empirical study that addresses literature gaps. CBT Programs in Education 3 Promoting Mental Wellness in Education with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Interventions Mental Disorders Epidemic in America The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) reported in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) that approximately 56% of US citizens will meet criteria for at least one mental disorder at some time in their lives; 43% will meet diagnostic criteria within the past 12 months (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). The US Surgeon General describes mental disorders as, “serious deviations from expected cognitive, social, and emotional development” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). While mental disorders are certainly a societal issue, perhaps most alarming is the prevalence in American youth. Kessler et al. (2005) reports that roughly half of all lifetime mental disorders will begin by age 14, while three-fourths will have begun by age 24. However, only 20% of all mental disorders in children will go reported (US Public Health Service, 2000; Collins, Westra, Dozois, & Burns, 2004). This is consistent with the Methodology for Epidemiology of Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents [MECA] (1996) which states approximately one in five US children and adolescents, aged 9 to 17, will experience at least minimum impairment to daily functioning in the form of a diagnosable mental disorder. Thus unfortunately, most mental disorders in children and adolescents will go unreported and subsequently untreated until they are severe enough to cause serious damages either because of the stigma associated with mental disorders or lack of access to treatment options (Collins et al., 2004). However, if mental disorders are identified and addressed at its onset, children and adolescents can be effectively treated (Mennuti, Christner, & Freeman, 2012). There is hope for the mental disorder epidemic afflicting America’s youth if preemptive action is taken accordingly. CBT Programs in Education 4 Many recommendations have been made regarding nationwide mental health issues. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as, “…not just the absence of mental disorder. It is defined as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (WHO, 2007). The National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment (2001) advised that treatment initiatives supersede current symptom reduction models and incorporate assessment and functionality of everyday environments (i.e. school, family, and community situations). The President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2003) reported that early recognition and intervention can reduce the likelihood of future mental disorders. Furthermore, the report claims mental health should be promoted in youth and schools should improve their assessment and ability to integrate treatment options. Finally, WHO (2009) proposes that in addition to increasing mental health care availability, mental health should be promoted at a self care and community care level in order to maintain the long term effectiveness of a desired mental health policy. WHO (2005) further suggests programs should provide young people with appropriate knowledge and skills to address resiliency and psychosocial functioning. These suggestions all propose that it is not enough to merely cure mental illnesses, but proper action must be taken in order to prevent their occurrence in the first place. Instead of viewing mental health through a deficit mindset of disorders, a paradigmatic shift to promote mental health is needed. Despite WHO’s definition of mental health, the general perception is merely more than the absence of a mental illness, an antonym of mental illness (Keyes, 2002). I recognize that the data above uses the phrase “mental health,” but for the CBT Programs in Education 5 sake of this paper, I will employ the term “mental wellness.” I suggest practitioners utilize the term “mental wellness” because mental wellness is a complex, multifaceted, and processoriented term that suggests lifelong competencies and skills. Rather than focusing on the negative stigmas of mental disorders that only afflict 56% of the population (Kessler et al., 2005), wellness incorporates competencies that all individuals can strive to attain. Furthermore, mental wellness suggests an attitude of prevention rather than a goal to simply treat mental illnesses. I believe that addressing mental wellness will be a more effective and enduring approach at resolving the mental disorder epidemic. The aforementioned policy suggestions assert that mental wellness initiatives must affect daily life, be promoted in youth, provide skills of resiliency and psychosocial functioning, and be maintained on an individual and community level. One environment that substantially addresses all these concerns and is consistent with the mental wellness ideology is education. Education and mental wellness have already converged through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Interventions. Before I define CBT, I must first explain why CBT is relevant to my argument. Framework of the Paper I began my paper with a heavy emphasis on national statistics from mental health organizations and reports in order to draw attention to the severity of the mental disorder epidemic in America. When these statistics are framed within educational contexts, mental wellness becomes almost impossible to ignore. The U.S. Department of Education’s 23rd annual report (2001) that states that the largest high school dropout rate of any disability are students affected by mental disorders at an alarming rate of approximately 50%. In addition to high student dropout rates, Epstein and Cullian (as cited in Mennuti et al., 2012) found that emotional and behavioral issues are associated with higher levels of truancy, suspension, tardiness, CBT Programs in Education 6 expulsion, attention seeking behavior, and poor social relationships. Thus, my argument’s main goal is to advocate for the implementation of an education program that is effective at preventing mental disorders. Yet, while valid suggestions have already been made for mental health in educational contexts, I believe one of the main barriers to addressing this epidemic is the deficit lens of mental disorders rather than the more holistic ideology encompassed in mental wellness. As a result, I will complete a literature review of one of the more widely accepted and therefore more widely implemented modalities to therapy and framework for educational programs--CBT. CBT is a natural fit in education because it is structurally similar to school settings. They both set an agenda, promote psychosocial skills, assign homework between sessions, monitor progress, and encourage adaptive behavior to deal with real or perceived stressors (Mennuti et al., 2012). I will focus my literature review on school based CBT interventions within adolescent populations (ages 11-17). However, I will also look at successful clinical treatments that have a manual as many of them have been, or can be transferred, to educational settings. As an educator I will frame my findings with a focus on learners and learning contexts in order to create a CBT curriculum with an educational focus rather than a traditional clinical focus. I will then assess CBT goals, assessments, homework assignments, teacher student relationships, classroom environments, and flexibility within manuals for what aspects a comprehensive CBT curriculum should include. Finally, I will propose where future research can be directed and how mental wellness can be promoted in education. Defining the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Model and Other Constructs Throughout my paper I will utilize the construct of CBT that evolved from Aaron T. Beck’s Cognitive Therapy (CT) that emphasizes the significance of cognition (underlying beliefs, attitudes, and assumptions) as the main etiology of psychological disorders (Beck, Rush, CBT Programs in Education 7 Shaw, & Emery, 1979). The goal of CT is to teach clients the following: “(1) to monitor his negative, automatic thoughts (cognitions); (2) to recognize the connections between cognition, affect, and behavior; (3) to examine the evidence for and against his distorted automatic thoughts; (4) to substitute more reality-oriented interpretations for these biased cognitions, and (5) to learn to identify and alter the dysfunctional beliefs (and behaviors) which predispose him to distort his experiences” (p. 4). In addition to Beck’s original conception of CT, I will include the Greenberger and Padesky (1995) diagram model that emphasizes the interconnected areas of thoughts, affects, behaviors, physiological reactions, and environment in CBT (see figure 1). It is important to recognize the dynamic nature of various factors and their interplay together in order to form a more comprehensive picture of clients’ issues. The terms referring to the broad category of mental disorders and specific internal disorders (depression, anxiety, and substance abuse) will be defined by individuals who meet the necessary criterion for mental disorders as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for mental disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Major Depression Disorder is classified as five (or more) of the following symptoms during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. Other criteria include (3) Significant (>5% body weight) weight loss or gain, or increase or decrease in appetite, (4) Insomnia or hypersomnia, (5) Psychomotor agitation or retardation, (6) Fatigue or loss of energy (7) Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt, (8) Diminished concentration or indecisiveness, (9) Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide. CBT Programs in Education 8 CBT in Adolescents I have focused my literature review on adolescents (children aged 11-17) because of the aforementioned epidemic of mental disorders in this population. Furthermore, adolescence is a formative period in emotional development marked by greater fluctuations in emotions. Although adolescents are in the process of developing greater emotional awareness and coping skills, many do not develop the necessary tools and may become more prone to mental disorders. Adolescents with mental disorders are at greater risk for academic issues, drug abuse, eating disorders, or juvenile delinquency (Santrock, 2007). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) based interventions are among the most widely practiced and best empirically supported methods of the psychosocial interventions (Elkins, McHugh, Santucci, & Barlow, 2011; Weisz, McCarthy, & Valeri, 2006). Over the past few years, the wealth of literature concerning CBT use with adolescents in therapeutic environments has expanded significantly (Weersing & Brent, 2006). While CBT has been used with younger children (Beidas, Benjamin, Puleo, Edmunds, & Kendall, 2010), children in the formal operational stage of Piaget’s cognitive development (older than 11) benefit the most from CBT interventions because they have fully developed the competencies of decentration, reversibility, infer causal reasoning, and elimination of egocentrism (Grave & Blissett, 2004). This research further raises awareness to the importance of mental wellness and the critical juncture of adolescence. CBT is one of the most prevalent treatments for mood disorders because its strong foci on internal cognitions and expectations, reinforcing behaviors, and subsequent emotional consequences that dictate general dispositions. CBT, or variations of CBT, have shown effectiveness at reducing symptoms of anger (Sukhodolsky, Kassinove, & Gorman, 2003), borderline personality disorder (Linehan et al., 2006), bipolar disorder (Lam et al., 2003), eating CBT Programs in Education 9 disorders (Fairburn et al, 2009), obsessive-compulsion disorder (Salkovskis, 1999), and alcoholism (Morgenstern & Longabaugh, 2000). There is strong evidence in support of the effectiveness and efficacy of CBT with adolescents in the treatment of internalizing disorders such as depression (Horowitz & Graber, 2006; Lewinsohn & Clarke, 1999) and anxiety (Kendall, 2006; Hollon, Stewart, & Strunk, 2006). As cited in Kavanagh et al. (2009) and Shirk, Kaplinski, & Gudmundensen (2009), depression is associated with functional impairment, low academic achievement, poor social relationships, substance abuse, self harm, and suicide. Depression is often a comorbid disorder associated with anxiety. Velting, Setzer, and Albano (as cited in Mennuti et al., 2012) found an connection between anxiety and academic underachievement, under employment, substance abuse, and low levels of social support. These internalizing disorders can have large implications, as maladaptive beliefs can negatively affect cognitive, social, emotional, behavioral, and physical aspects of adolescents’ lives. I believe that education’s main goal is to promote these skills; therefore, it is critical that students operate at optimal levels in order to achieve their maximum potential. In order to concretely demonstrate how depression and anxiety may present themselves in regards to learners in learning contexts, I will provide comprehensive examples of each mental disorder. Imagine James, an 11 year old White boy. Although he appears bright, James is extremely shy and rarely participates in class discussions or activities. He avoids answering questions and never asks for clarification when he is confused about material or assignments. Rather than present in front of the class or collaborate with others in group settings, James accepts failing grades. He appears to have limited interaction with his peers and is rarely discussed in teacher staff meetings. James meets sufficient criteria for Social phobia. Now imagine Shannon, a 13 year old girl Black girl. At one point Shannon was a high achieving and CBT Programs in Education 10 engaging student that was active with her peers and teachers and rarely misbehaved. However, over the past three months Shannon has been apathetic and disinterested in almost all activities. She sleeps in class and is lethargic when she is awake. She has difficulty concentrating and has failed her most recent exams. When the teacher attempts to remediate, Shannon claims that she is worthless and not smart enough to do well. Shannon meets sufficient criteria for a Major Depressive Disorder of Major Depressive Episode. Both James and Shannon provide concrete examples of how depression and anxiety can affect learners and educational settings. Clearly the students in these examples are not reaching their maximum potential. I believe CBT can help them overcome these limitations, providing the students an opportunity to be happy, healthy, and wise. CBT in Educational Settings In this section I will discuss the educational components of popular CBT programs used in educational settings with specialized populations. Programs like Coping Cat, Penn Prevention Program (PPP), Adolescent Coping with Depression course (CWD-A), Treatment For Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS), and Taking ACTION are among the most popular CBT intervention manuals used in school (Mennuti et al., 2012). Mennuti et al. (2012) further explains each manual fits the American Psychology Association (APA) standards for best practices founded on evidence based practices. I will synthesize the curricular components of CBT in the areas of goals, assessment, homework, student/teacher relationships, classroom environment, and personalization/flexibility in order to build a more comprehensive understanding of what components have been effective and need to be included in a complete CBT curriculum to promote mental wellness. It is my hope that this literature review can easily CBT Programs in Education 11 converted into a new curriculum or manual that accounts for educational factors in addition to clinical factors. Because CBT is a therapeutic intervention designed to treat mental disorders, its use in school has been used with primarily specialized populations. Specifically, adolescents who display overt symptoms of emotional disturbance like depression, anxiety, substance abuse, ADHD, school refusal, and behavioral disorders are often the targets of current mental health assessments and subsequently receive treatment (Mennuti et al., 2012). This certainly has obvious benefits to this population as delivering mental wellness services in school settings helps provide treatment options to a larger population of individuals who may otherwise be limited by transportation, costs, or scheduling conflicts (Elkins et al., 2011). Thus the wealth of literature among CBT in specialized populations is growing. However, there remains a large deficit of research among the majority of adolescents who are not diagnosed with mental disorders. By addressing mental wellness, all children can begin to receive potentially beneficial CBT interventions and we can begin to correct another hidden achievement gap that plagues the American educational system. CBT Goals in Education. The goal of CBT interventions is to help individuals demonstrate how they can control and regulate their own emotions by identifying automatic thoughts, examining the accuracy of their beliefs, and changing behaviors to reinforce new beliefs (Beck et al., 1979). Thus, the cognitive piece of CBT should be the main focus of interventions with the affective and behavioral components as secondary components. This is consistent with findings from Sukhodolsky et al. (2004) that problem solving treatments that focused on learning how to think through causes and consequences were more effective at reducing internalized emotions than CBT Programs in Education 12 interventions that relied solely on relaxation and positive imagery education. In addition, changes in negative automatic thoughts were the strongest mechanisms of change in depression symptoms (Kaufman, Rohde, Seeley, Clarke, and Stice, 2005). Furthermore, sufficient changes in automatic thoughts had consistent effect sizes for more extensive periods of time in follow ups (Kaufman et al., 2005). One effective manner to teach core tenets of CBT is through cognitive distortions, or thinking errors that can lead to maladaptive misinterpretations of reality (Mennuti et al., 2012). Cognitive distortions and other cognitive components are a major mechanism of CBT and can easily be taught to students using traditional pedagogical strategies since they have a large academic element. While CBT school interventions remain primarily cognitive, there are other components that affect treatment outcomes. Interventions with ten or more sessions were more effective than shorter programs (Kavanagh et al., 2009). As a result, CBT should be taught over time with periodic reinforcement afterwards. Other issues regarding scope and curriculum settings were the time of year interventions were delivered. Treatment responses were greater for interventions that began during the school year and continued into the summer only if participants reported a greater number of school related problems. Otherwise interventions in the summer had no other effect (Shamseddeen et al., 2011). Thus, school problems are relevant to the treatment of depression and must be accounted for in treatment plans. Kennard et al. (2005) often explicitly taught social skills training in the form of assertiveness training, social interactions, and communication skills to help students build social interaction and peer support. Students with social anxieties or depression that are made worse with communication issues would benefit from these components. Overall, the goal of CBT should remain primarily cognitive, but social factors amongst participants should also be accounted for. CBT Programs in Education 13 Assessment I have elaborated on the desired results of CBT as the recognition of maladaptive beliefs and the subsequent substitution of new interpretations of reality which allow individuals to think and act more adaptively accordingly to stress (Beck et al., 1979), I will now explain how CBT has been measured in school settings. Instead of launching into a literature review of successful components of CBT curricula, it is critical that practitioners understand how success has been determined. This sequence is consistent with Wiggins and McTighe’s (2005) backwards design framework where the assessment stage precedes lesson components. CBT was developed with the purpose to treat mental disorders, and thus it has primarily been used with specialized populations. As a result, assessments typically gauge effect sizes of CBT interventions in regards to clinical progress, not cognitive or academic progress. Broad surveys, focus groups, self report measures, coded observations, and interviews are typically used to assess changes in mood or cognition. Specifically the Beck Youth Inventories, Second Edition (BYI-II), Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) are common screening and pretest/post-test data collection methods (Mennuti et al., 2012). While these assessments accurately gauge the absence or presence of mental disorders, they do not assess other skills that all individuals can strive to attain. There is a significant gap of evidence based research on assessing CBT interventions is school settings (Mennuti et al., 2012). Due to this lack of research, I will propose components of assessment that can be used to evaluate school based mental wellness programs. Much like the main concept behind mental wellness, a proper assessment of CBT tasks should include a comprehensive picture of the client’s strengths and weaknesses. (David-Ferdon CBT Programs in Education 14 & Kaslow, 2008). This will better serve practitioners to make appropriate treatment decisions more efficiently and effectively. Using students’ strengths will then increase student engagement and help instructors more accurately assess knowledge (David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008). For example, a student with strong verbal skills should be asked to explain their thoughts and emotions with others, not write about them in thought records. Role play with individuals in the TADS helped provide students with natural contexts where their maladaptive ideations would commonly manifest themselves (Kennard et al., 2005). Since these role plays involve simulated settings of real restraints, they provide accurate assessments in the form of a performance task (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). More complete assessments will lead to greater desired results and increase the effectiveness of CBT interventions. A consistent task among many CBT interventions that involves a formative assessment piece is homework. Homework Component Assigning homework in CBT is a fundamental element as it helps individuals construct their own understanding and increase the likelihood of transfer in more natural contexts. Greenberger and Padesky (1995) have a comprehensive workbook often used as homework that includes thought records, worksheets to recognize automatic thoughts, questionnaires that ask for evidence, and activity scheduling. Not surprisingly, greater compliance with homework is associated with better treatment outcomes (Kennard et al, 2005). Students that attended CBT groups and completed more homework assignments had an increase in other class participation and also achieved higher grades (Ruffolo & Fischer, 2004). In addition to increasing class participation, completing homework tasks without the help of parents helped students increase their levels of accountability and self confidence, which are often issues amongst depressed and anxious individuals (Kendall & Barmish, 2007). While CBT homework can increase agency CBT Programs in Education 15 through intrapersonal skills, interpersonal skills are also an important competence. Compliance with assignment completion was associated with a higher levels of reported therapeutic relationship (Kennard et al., 2005). Overall, homework is a critical piece that must be included in CBT interventions for additional practice with core concepts, increases in self confidence, and development of student teacher relationship. Relationship of Teacher and Student One of the most influential components of education is the relationship between student and teacher. CBT is no different as the therapeutic relationship has profound effects on treatment (Beck et al., 1979). The teacher-student relationship is particularly important in dealing with adolescents. Auger (as cited in Ruffolo & Fischer, 2009) suggests having a trusted adult to confide in and discuss issues helps students cope with depressive symptoms. While any caring adult can potentially fill this role, interventions provided by existing school staff appeared to have a greater effect than those administered by non school psychologists or researchers (Kavanagh et al., 2009). While CBT experts (psychologists, social workers, and researchers) may have more practice with the therapeutic relationship, they have little to no actual rapport with students; interactions are typically limited to the amount of sessions available. However, teachers and school staff are more familiar with students and their culture. They do not need to devote time towards developing the therapeutic relationship; it already exists. However teachers do need additional training and providing teachers with the necessary tools to recognize overt signs of internalizing disorders will help identification of students who may be at risk for CBT interventions (Elkins et al., 2011). School teachers and staff can use CBT interventions as a tool to increase parental and community involvement in student’s academic lives. Classroom Environment CBT Programs in Education 16 The development of a rich, safe, and community driven environment is of the utmost importance in learning (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). Collaboration between students, families, and therapists is critical in classrooms that strive view learning as a process. When students have a growth oriented mindset (Dweck, 2007) they prescribe to key tenets of mental wellness- a goal to strive for maximum potential. CBT Interventions that encourage mental wellness were explicit in their instructional policies. Instructors made clear that activities would not be evaluated for grammar or spelling, would not be graded, and had no right or wrong answers were effective at reducing anxiety (Kendall & Barmish, 2007). Furthermore, teachers openly expressed attitudes where symptoms were viewed as manifestations of a disorder, not a direct fault of any single individual (Kennard et al., 2005). However, instructors did not just express their attitudes, they fostered an environment where students shared positive attitudes and cooperated together. Ruffolo and Fischer (2004) indicated that the group settings of CBT group sessions helped increase social bonds and engagement among students. These positive attitudes helped create opportunities for families to communicate with educators and schools. When families and communities are viewed as equal partners in education, both students and schools benefit. David-Ferdon and Kaslow (2008) found that parental and family support increases the effectiveness of CBT treatments, especially when used to treat youth from various cultural and ethnic backgrounds. This finding is particularly important since internalizing disorders have a large social component which can be further damaged with phenomena such as stereotype threat (Steele & Aronson, 1995). Mental wellness is made even more complex when practitioners and students have cultural conflicts. However, these cultural conflicts can be addressed by establishing trust, learning the family system, and collaborating with family members (Mennuti et al., 2012). Adolescents with higher reported levels of stress pre treatment CBT Programs in Education 17 were more likely to maintain depression diagnoses (Shirk et al., 2009). Therefore it is important to recognize how issues of race, culture, gender, and sexuality in CBT interventions affect student stress levels. Regardless of race, collaboration with families is beneficial to a good classroom environment. Personalization and Flexibility School-based CBT needs to be flexible and account for students’ needs (Elkins et al., 2011; Kendall & Barmish, 2007; Kennard et al., 2005). When manuals are flexible, they can be personalized and better address student needs. One key pedagogical strategy involves being aware of students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes to make material relevant to individual learners (Bransford et al., 2000). Because CBT interventions typically involve adolescents who are depressed or anxious, students may have significant cognitive impairment due to the nature of mental disorders. They may need more time to complete tasks or repetition with instruction. As a result, teachers should remain patient and provide multiple forms of instruction, especially when dealing with issues regarding affective pieces (Kennard, Ginsburg, Feeny, Sweeny, & Zagurski, 2005). Creative and interactive formats can help increase client engagement and comprehension Elkins et al., 2011). Individualized plans that helped students walk through anxieties using graduated exposure tasks were used in the “Show That I Can” (STIC) homework tasks (Kendall & Barmish, 2007) and in the TADS Manual (Kennard et al., 2005). Activities in TADS were personalized to help determine the adolescent’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that that commonly caused students problems. By utilizing actual student issues manuals were more specific and yielded larger results CBT Programs in Education 18 Future Implications While CBT interventions with specialized populations are widely available, these studies still approach CBT as a clinical treatment. Very few educational implications could be drawn as the goal is to still diagnose and treat mental disorders. There is a sparse amount of research with CBT curriculums in populations of individuals without a diagnosed mental disorder. I have conducted a comprehensive literature review of the best practices in CBT interventions with adolescents in hopes that a full CBT curriculum can be delivered to all populations students. Elkins et al., (2011) reported that there were no known negative effects in non-diagnosed individuals of a universal CBT program. While this is a good start, this evidence is still framed through the generally held deficit mindset of mental health. I have purposefully set up my paper through the lens of mental wellness in order to help promote competencies that may eventually prevent mental disorders, rather than solely treat them. Although the field of CBT in education is growing, further evidence must be gathered. Demographic issues of race, socio-economic status, gender, ethnic background, and sexuality have yet to be researched thoroughly and will have a huge effect on how CBT interventions are delivered. Furthermore, I did not encounter any longitudinal studies that spanned across many years. One potential empirical investigation that may be of interest to researchers may include a longitudinal study of an existing CBT manual with non diagnosed students. This could be compared with another population at the same school of children with diagnosed mental disorders or who are considered to be at risk. CBT Programs in Education Figure 1. (Adapted from Greenberger & Padesky, 1995) Environment Thoughts Physical Reaction houghts Behaviors Mood 19 CBT Programs in Education 20 References American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Satistical manaual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washing, DC: Author. Augustyniak, K.M., Brooks, M., Rinaldo, V.J., Bogner, R., & Hodges, S. (2009). Emotional regulation: considerations for school-based group interventions. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 34, 326-350. Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press. Beidas, R.S., Benjamin, C.L., Puleo, C.M., Edmunds, J.M., & Kendall, P.C. (2010). Flexible applications of the coping cat program for anxious youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17, 142-153. Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (Eds.) (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington DC: National Academy Press. Calear, A.L., & Christensen, H. (2010). Systematic review of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for depression. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 429-438. Collins, K.A., Westra, H.A., Dozois, D.J.A., & Burns, D.D. (2004). Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depression: Challenges for the delivery of care. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 583-616. David-Ferdon, C., & Kaslow, N.J. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 62-104. Dweck, C.S. (2007). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. CBT Programs in Education 21 Elkins, M., McHugh, K., Santucci, L., & Barlow, D. (2011). Improving the transportability of CBT for internalizing disorders in children. Clinical Child Family Psychology Review, 14, 161-173. Grave, J., & Blissett, J. (2004). Is cognitive behavior therapy developmentally appropriate for young children? A critical review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 399420. Greenberger, D., & Padesky, C. A. (1995). Mind over mood: Change how you feel by changing the way you think. New York: Guilford Press. Hollon, S. D., Stewart, M. O., & Strunk, D. (2006). Cognitive behavior therapy has enduring effects in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 285-315. Horowitz, J.L., & Garber, J. (2006). The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 401-415. Kaufman, N.K., Rohde, P., Seeley, J.R., Clarke, G.N., & Stice, E. (2005). Potential mediators of Cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with comorbid major depression and conduct disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 38-46. Kavanagh, J., Oliver, S., Lorenc, T., Caird, J., Tucker, H., Harden, A., Greaves, A., Thomas, J., & Oakley, A. (2009). School-based cognitive-behavioural interventions: A systematic review of effects and inequalities. Health Sociology Review, 18, 61-78. Kellner, M. H., Bry, B.H., & Salvador D.S. (2008). Anger management effects on middle school students with emotional/behavioral disorders: Anger log use, aggressive and prosocial behavior. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 30, 215-230. CBT Programs in Education 22 Kendal, P.C., & Barmish, A.J. (2007). Show-that-I-can (homework) in cognitive behavioral therapy for anxious youth: Individualizing homework for Robert. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 14, 289-296. Kennard, B.D., Ginsburg, G.S., Feeny, N.C., Sweeny, M., & Zagurski, R. (2005) Implementation challenges to TADS cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 12, 230-239. Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K., Walters, E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593-602. Keyes, Corey (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 43, 207–222. Koch, S.P. (2010). Preventing student meltdowns. Intervention in School and Clinic, 46, 111117. Lewinsohn, P.M., & Clarke, G.N. (1999). Psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 19, 329-342. Mennuti, R.,B., Christ, R.W., & Freeman, A. (Eds.). (2012). Cognitive Behavioral Interventions in Educational Settings: A Handbook for Practice (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. Morgenstern, J., & Longabaugh, R. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence: a review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiction, 95, 1475-1490. CBT Programs in Education 23 The National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment, (2001). Blueprint for Change: Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Washington, D.C. Pickover S. (2010). Emotional skills-building curriculum. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 3, 52-58. Phillips, J.H., Corcoran, J. & Grossman, C. (2003). Implementing a cognitive-behavioral curriculum for adolescents with depression in the school setting. Children & Schools, 25, 147-58. Rait, S., Monsen, J.J., & Squires, G. (2010). Cognitive behaviour therapies and their implications for applied educational psychology. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26, 105-122. Rogers, G.M., Reinecke, M.A., & Curry, J.F. (2005). Case formulation in TADS CBT. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 12, 198-208. Ruffolo, M.C., & Fischer, D. (2009). Using an evidence-based CBT group intervention model for adolescents with depressive symptoms: Lessons learned from a school-based adaptation. Child & Family Social Work, 14, 189-197. Santrock, J.W. (2007) Adolescence (11th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Dulcan, M. K., Davies, M., Piacentini, J., Schwab-Stone, M, . E., Labey, B. B., Bourdon, K., Jensen, P. S., Bird, H. R., Canino, G., & Regier, D. A. (1996). The NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): Description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA Study. Methods for the epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 865-877. CBT Programs in Education 24 Sahmseddeen, W., Clarke, G., Wagner, K.D., Ryan, N.D., Birmaher, B., Emslie, G., Asarnow, J.R., Porta, G., Mayes, T., Keller, M.B., & Brent, D.A. (2011). Treatment-resistant depressed youth show higher response rate if treatment ends during summer school break. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 11401148. Shirk, S.R., Kaplinski, H., Gudmundsen, G. (2009). School-Based cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: A benchmarking study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 17, 106-117. Shirk, S.R., & Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variable in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 452-463. Squires, G. (2010).Countering the argument that educational psychologists seed specific training to use cognitive behavioural therapy. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 15, 279-294. Steele, C.M., & Aronson, J. (1995). "Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811. Sukhodolsky, D.G., Kassinove, H., & Gorman, B.S. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anger in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 247-269. Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study Team. (2004). Fluoxetine, cognitivebehavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment For Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292, 807-820. CBT Programs in Education 25 U.S. Department of Education, (2001). Twenty-third annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Washington, D.C. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1999). Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. U.S. Public Health Service (2000). Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services. Wiggins, G, & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Weersing, R.V., & Brent, D.A. (2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15, 939-957. Weisz, J.R., McCarthy, C.A., & Valeri, S.M. (2006). Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychology Bulletin, 1, 132-149. Wolfe, V.V., Dozois, D, J., Fisman, S., & DePace J. (2008). Preventing depression among adolescent girls: pathways toward effective and sustainable programs. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 15, 36-46. World Health Organization (2005). Child and Adolescent Mental Health Policies and Plans. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. World Health Organization (2007). What is mental health? Retrieved from http://www.who.int/features/qa/62/en/ CBT Programs in Education 26 World Health Organization (2009). Improving Health Services and Systems for Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Zyromski, B. & Joseph, A.E. (2008). Utilizing cognitive behavioral interventions to positively impact academic achievement in middle school students. Journal of School Counseling, 6.